Night’s candles are burnt out, and jocund day stands tiptoe on the misty mountain tops

Spanish life is not always likeable but it is compellingly loveable

- Christopher Howse: 'A Pilgrim in Spain'

NOTE: Info on Galicia and my Guide to Pontevedra city here.

Covid

Spain: The Prime Minister claims that Spain is "100 days away from achieving herd immunity”. Yes, well. Maybe.

Cosas de España/Galiza

The Minister of Foreign Affairs blames Isabel Ayuso’s ‘Libertad’ program for Madrid for Spain being Amber: “The Madrid region president says that what matters in this country is libertad – going out for beers, going to the bullfights, out and about whenever and wherever they want. What's more, those who say that you have to respect social distance rules and you have to be prudent and responsible are accused of being communists. And what happens is that the infection numbers from Madrid, undoubtedly the worst in the country, count towards the average that the UK uses to put Spain at Amber”.

I’m confused about the new speed limit of 30kph which was supposed to be introduced in villages and towns yesterday. On one of the (admittedly) main roads into and out of Pontevedra city, there are still 80, 60 and 40 signs. And down the bottom of my hill (30 for a long time now), it’s still 50 in a residential area. On said main road yesterday, there was a police patrol at the surprising hour of 11am. Unlikely to be for breath testing, so possibly fining folk doing more than 30 as they approached the city. I wouldn’t be at all surprised.

Talking of roads . . . There were humungous tailbacks at the exits for Vigo airport yesterday, in both directions. This is because one of the main Covid testing centres is in an exhibition hall there. I imagine quite a few folk missed their flights.

Life in Spain . . . When I got a train back from Vigo yesterday, it was 75% empty but, of course, someone was sitting in my allocated seat. And, as usual, there was the standard profuse Spanish apology - on the well-established principle that it's easier and less inconvenient to say sorry than to obey rules.

Portugal

The possible price of unity . . . Thousands of British holidaymakers due to visit Portugal next week may face difficulties entering the country as the EU has banned non-essential travel from non-EU states. To ignore the ban would be diplomatically delicate because Portugal holds the EU presidency. The cabinet will discuss the issue today. If the issue isn't resolved, thousands of British visitors could be turned away at the airport. By the time the Champions League final is due to be held in Porto on May 29, which is due to be confirmed by Uefa today, officials believe that the EU will have ended the non-essential travel ban and British fans will be able to enter the country without difficulties. However, it is thought that the earliest that the EU will change the ban will be Wednesday, 18 May.

The UK

You can't keep AEP down. See the first article below for his optimistic take on the UK economy: Britain’s coiled-spring recovery is now an economic fact, and it looks even stronger than the most giddy optimists had dared to hope.

You might well think the problem of Scotland for the UK is the same as that of Cataluña for Spain and that most non-Scottish Brits would be against that country’s independence. If so, you’d be wrong on both counts. See the second article below.

The USA

Trump labels Liz Cheney ‘A bitter, horrible human being’. Yet more evidence of the man’s indulgence in ‘projection’.

The Way of the World

Amazon ratings. . . Who's going to be surprised?

Social media

Social media was supposed to to free us all - but it's resulted in a free-for-all where no-one's free, certainly not children

English

1. Well, I never . . . The word ‘farm’ came to English from Latin, via Norman French. Its original meaning was ‘a fixed payment or rent for a plot of land.’

2. 'Price matched to' = 'Costs the same as'

Quote of the Day

Thanks to the pandemic, Boris Johnson – the playboy of politics, the Don Juan of Downing Street, the Conservative Casanova – found himself having to make casual sex a criminal offence.

Finally . .

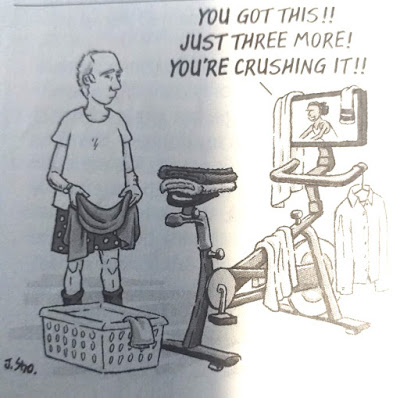

That Peleton ad that I hate . . .

THE ARTICLES

1. As Britain booms again, let us scrub ‘despite Brexit’ from the lexicon. By early next year the UK is set to close the entire economic gap with the eurozone that has built up since the Brexit referendum: Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, Telegraph

Britain’s coiled-spring recovery is now an economic fact, and it looks even stronger than the most giddy optimists had dared to hope.

Barring any upset from Covid variants or a bond rout, the British economy will be the G7 star this year. That is not in itself surprising. Part of this is a mechanical V-shaped rebound from last year’s exaggerated statistical dip.

But what may surprise some is the real possibility that the UK will grow faster than a slowing China in 2022 as Rishi Sunak’s “super deduction” on plant and machinery investment unlocks a treasure of excess corporate savings.

It may also outgrow Joe Biden’s America, despite his fiscal trillions and a compliant Federal Reserve. That would crown the first authentic year of Brexit – without pandemic distortions – fundamentally changing global perceptions of Britain’s post-EU reinvention.

The 2.1% jump in GDP in March blew away consensus. It silences persistent talk that the UK has gained little from early vaccination and is still essentially moving in economic lockstep with Europe. Blockbuster growth of 5pc (20pc-plus annualised) is on the cards for this quarter.

The pace is so torrid that Capital Economics thinks the UK may regain its pre-pandemic level of output by late summer, with little or no permanent scarring. Investec has pencilled in the sorpasso for September, saying growth could “easily exceed” 8pc this year.

If so, the UK will cross its pre-Covid line long before the eurozone, and a year ahead of the Club Med bloc. On a nominal GDP basis, it has already matched Germany and overtaken France, Italy, and Spain.

This is a remarkable turn of fortunes given that the OECD, IMF, and other voices of the global establishment were predicting something close to perma-slump for these benighted isles in 2021 and 2022. The OECD forecast in December that the UK would be the economic basket case among developed states this year (along with Argentina), limping into 2022 with output still 6.4pc below pre-Covid levels.

It is well known that British households have amassed £130bn of excess savings during Covid. We will find out soon how much of this is pent-up spending waiting to explode. But what is less known is that UK companies are sitting on a further £100bn, some 50pc above normal levels. “We think this is even more important,” said David Owen from Jefferies.

“The super deduction has cut the effective marginal rate of corporation tax to zero. Companies have all this cash sitting on their balance sheets and it’s a no brainer for them to invest,” he said. The latest CBI survey shows that investment intentions are a whisker shy of thirty-year highs.

The Bank of England thinks business spending on plant and digital technology will rise by 7pc this year and 13pc next year, matching the IT blitz during the dotcom boom in 1998.

“It won’t be the Roaring Twenties but we are about to ride an investment wave. It’s a Covid story, a net-zero story, and a Brexit story, all coming together in a very optimistic way,” says Owen.

The trade data for March showed that goods exports to the EU have largely regained their prior levels and are above flows last summer when the UK was still part of the single market. Even exports of fish and shellfish have returned to normal.

“People were far too pessimistic about the magnitude of the hit. The idea that there was going to be a seismic fall in trade after Brexit was always rubbish. Companies adapt,” says Julian Jessop, a fellow at the Institute of Economic Affairs.

This export rebound comes despite some harassment. The National Pig Association says 30pc of all UK consignments to the EU are being checked, far higher than for other third countries. Just 1% of pig imports from New Zealand are checked. I will add British pork to my next shopping trip.

We can start to separate teething problems from the structural effects of Brexit, and start to make a coherent judgement on where we stand. What is clear already is that British firms are learning to cope with customs red-tape – because they have little choice, and because the size of the EU market makes it worthwhile. The numbers complaining of UK border disruption have fallen to 7pc from 35pc in early February.

What is equally clear is that EU firms have lost UK market share to global competitors. Imports from the rest of the world are growing twice as fast, and this divergence is likely to widen when Britain ends its unilateral waiver on customs clearance for EU goods and imposes reciprocal curbs.

The EU’s decision to make cross-Channel trade more cumbersome than flows under other trade deals – as a penalty for refusing to remain a full regulatory satellite – has had one salient consequence so far: it has hurt small European exporters.

There is much that can still go wrong for the UK. Simon Ward from Janus Henderson says the red-hot growth in the money supply risks a “major blow-out” in the balance of payments and ultimately a sterling upset.

“What is concerning is that the UK’s money growth has overtaken other major areas. It’s crazy that they are still doing QE,” he says. His measure of broad money growth – non-financial M4 – topped 16% earlier this year, the fastest pace since the Lawson credit boom in the late 1980s. This will catch fire if velocity returns to normal.

The Bank of England has underestimated the strength of the rebound and is coming under increasingly ferocious criticism from monetarists. It will have to navigate a treacherous exit from over-stimulus. Any delay in tightening only makes it harder.

Europe too will have its boom. But recovery will start later, due to third wave lockdowns in April. It will be less exuberant when it comes. Industrial bottlenecks will be a bigger relative headwind for the manufacturing hubs of Germany and Italy. Fiscal stimulus is greater than it was but is half-hearted compared to Bidenomics.

The Commission’s Spring Forecast released on Wednesday said the eurozone would grow 4.3pc this year and 4.4pc next year, implying that most countries will not recoup their lost GDP before 2022.

The Recovery Fund remains totemic in EU rhetoric but is proving smaller than headline figures suggest. Submissions so far amount to just €433bn, too little to move the macroeconomic needle for the bloc as a whole over a five-year period. Most countries have shunned the loan component, with the notable exception of Mario Draghi’s Italy. “It’s lacklustre,” said Bert Colijn from ING.

My bet: by early next year the UK will have closed the entire economic gap with the eurozone that has built up since the Referendum shock in 2016; by the end of next year it will have regained its pre-pandemic trajectory, almost as if Covid had never happened.

At that point the UK’s maligned economy will have overtaken the eurozone big four and established an outright lead of around 2% of GDP. Can we then scrub the words “despite Brexit” from the journalistic lexicon?

2. Boris risks furious English backlash by throwing more money at Scotland. Most English voters couldn’t give a stuff if Scotland choses to leave the union - and a sizeable minority would positively welcome it. Jeremy Warner, Telegraph

The pound has seen something of a resurgence, against both the dollar and the euro, since last week’s super-Thursday elections. The spurt in part reflects relief that Scottish independence has become that little bit less likely.

Notwithstanding the pro-separatist majority that now exists in the Scottish Parliament, the fact is that Nicola Sturgeon was denied the majority she sought for her own party, weakening the legitimacy of demands for a second referendum. In the event, more votes were cast for pro-union parties than separatist ones.

Small wonder that the First Minister shrinks from the idea of an immediate second vote; she would struggle to win it if held tomorrow. Her gamble is that Boris Johnson’s determination to deny any question of a second referendum will play into her hands, and she could be right.

In this age of identity politics, nothing is more likely to sustain Sturgeon in her position than lecturing from Westminster about how much worse off Scots are going to be if they vote for independence, and for good measure to deny them another chance to vote on it anyway. Once again she plays the downtrodden Scots card, subjugated by bullying English Old Etonians.

Yet it is not just North of the Border that Boris Johnson needs to win the argument for the union; he also has to win hearts and minds in England, where the challenge might reasonably be thought just as big. It is admittedly improbable in the extreme that the English will ever be given a vote on the future of the union, but if they were, chances are they would as happily vote for Scottish separation as the Scots themselves.

Surveys repeatedly show that most English voters couldn’t give a stuff if Scotland chooses to leave, and that a sizeable minority would positively welcome it. Attitudes are harder still when it comes to Northern Ireland, which in per capita terms enjoys an even bigger fiscal transfer from the rest of the country than Scotland.

Scotland may be the epicentre of the debate, but ultimately, the future stability of the UK depends as much on consent south of the border as it does among Scots.

Many English voters already think far too much money is spent keeping Scotland onside. Any more risks a serious backlash.

Ever greater levels of devolution are the price Westminster has deemed necessary to keep the union together. Yet chucking money and powers at Scotland is not going to be a sustainable solution if it ends up alienating everyone else. If going “federal” is the answer, it won’t work unless all are offered similar levels of political and economic autonomy.

The current devolution settlement is already intolerably asymmetric. Many of Scotland’s domestic affairs - including health, education and public transport - are determined by Scotland’s devolved institutions, over which England holds little sway. Yet public policy for England itself continues to be decided by UK-wide institutions in which Scotland does have a say through representation at Westminster.

This asymmetry used to be called the “West Lothian Question”, a term coined by Enoch Powell after the MP for the Westminster constituency who first raised the issue, Tam Dalyell. The “English votes for English laws” reforms of the first Cameron government only partially answered the complaint.

With the Johnson Government enjoying a “stonking” great majority at Westminster, constitutional issues such as these might seem of little more than academic interest. They hardly matter. Scottish MPs cannot influence what Johnson does in England.

What does matter, however, is the size of the subsidy paid by the rest of the country to support the devolutionary settlement. Analysis by the Office for National Statistics shows that in 2018-19, Scotland’s fiscal deficit was around £2,450 per person. In other words, they spend that much more per person than they raise in taxation.

The numbers that underlie this statistic further enhance the sense of English grievance. Tax revenues per person are about the same as the average for the rest of the UK, but spending is much higher - £14,500, against a little under £12,600 for England. If you want to know why Scotland can splash out on a 4pc pay rise for health workers, but England can seemingly afford no more than 1pc, there you have it.

True enough, the per capita fiscal deficit for Wales and Northern Ireland is even bigger, as indeed it is for the more deprived regions of England, including the North East and North West. The difference is that all these areas of the UK are considerably poorer. It is the shortfall in tax revenues, not the excess in spending, which makes the difference.

Scots should be careful what they wish for; many voters south of the border would gladly see them go. Yet English nationalists too should be worried by the logic of such thinking. Reductio ad absurdum, the same argument can be applied to the English regions.

To the extent that there are any fiscal surpluses to be had at all in the UK these days, they all come from London, the South East, and East Anglia. Why should rich Londoners subsidise poor Northerners? The old heptarchy of seven sovereign Anglo Saxon nations beckons. Refusal to cross-subsidise between regions would split the country asunder.

In any case, selling the merits of the union to the English is perhaps as big a challenge as selling them to the Scots. As Boris Johnson must know from his success in red wall constituencies, identity politics have become as powerful a force south of the border as north of it.

Yet despite the seemingly one-way flow of money, the bottom line is that the English have as much to lose as the Scots from the death of the union. Scotland is just 6.5pc of total UK GDP, so in simple economic terms, its loss might not seem of much importance.

Even so, a lot of things begin to unravel once the union is gone - the UK’s position on the UN Security Council, its independent nuclear deterrent, its military credibility and its still-potent soft power around the world to name but some of them.

International perceptions matter. What chance for Global Britain once globally insignificant? Scottish separation would be as much the end of an era for England as for Scotland, and not in a good way.