The story of a rose

Friday, June 27, 2025

Pink therapy. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Several years ago, I received a rose bush as a gift from my dear friend, Jenny. She bought it at a street market in Pruna, a village in the Andalusian hinterland that few people have probably heard of. The rose lived on our terrace for several years in increasingly larger flowerpots. However, no matter where we moved her, whether we gave her new soil or more nutrients, or spoke nicely to her, we only got a few meagre buds during the entire summer season. It was clear that this plant did not thrive in the place where she lived.

One day, we brought her to our organic huerto (allotment garden), dug a large hole in the clayey soil and planted it next to our ‘lavender tree’. The rose settled in almost immediately and started growing out of control. It was as if she had finally found her home. Today, she is a huge bush from which we can cut half a dozen long-stemmed, shockingly pink, heavenly-scented roses every time we visit our garden patch between early May and late November.

The rose in her new home. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The rose from Pruna has become my colour and scent-therapy, because one cannot help but be delighted by her presence. And it is also a joy we happily share with neighbours and acquaintances who have become equally addicted to our rose.

Pink compost! Photo © Karethe Linaae

The province of Málaga, the region of Andalucía and Spain are all places where rich colours surround one. Take the different earth tones - from chalky white and golden yellow to salmon, rust colour and reddish purple. Or all the shades of green in nature, and not to forget the rich blue tones of the sea that go from light turquoise to deep cobalt. Of course, the Spanish food is a colour-chapter in itself, and what about the colourful flamenco culture?

Flamenco dress in window. Photo © snobb.net

Research in psychology and design shows that colour stimuli can affect the emotional areas of our brain. Colours can therefore be mood-enhancing. Strong, bright and highly pigmented colours can have a vitalising effect on our mood and psyche. Being bold and standing out from their surroundings, they can also make us feel more energetic. Warm colours can evoke feelings of happiness, energy, and positivity, while calming and natural hues such as green and blue can reduce stress and promote relaxation. These are therefore often used in therapeutic environments.

Hues. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Surrounding ourselves with colours can make us ‘blossom.’ And just as some of us have lived in places and been in situations where we may not have been able to flourish as much as we wanted or are capable of, we, like our vibrant rose bush, may find a better and more fertile ground in the colourful, bright and cheery Andalucía.

Pink night sky. Photo © Karethe Linaae

2

Like

Published at 12:48 PM Comments (2)

2

Like

Published at 12:48 PM Comments (2)

Our ‘Home’ in Tangier - Boutique hotel with rock band owners

Friday, June 20, 2025

La Maison de Tanger seen from the garden. Photo © Karethe Linaae

On rare occasions when travelling, one finds a lodging where one feels completely at home. For me, it has only happened a couple of times. Once at an Inn on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, after a secret nuptial ceremony, and once in a picturesque Haveli in Pushkar (famous for its camel races) in Rajasthan. But then, we discovered La Maison de Tanger in Morocco, and there it was again – this feeling of having come ‘home’. My husband and I have returned several times since, and when we finally met the rock musician owners, it became clear why this North African refuge is so unique. So, if you are looking for that special home away from home, join me on a trip across the Strait of Gibraltar to our 'home' in Tangier.

Tea time on the terrace. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

What is a home, anyhow? It’s where someone lives - a house, a flat, a castle or a tipi. But beyond a physical dwelling, a home is a feeling. Subtle elements such as colours, smells, sounds, and the general vibe contribute to this sensation, which is sadly lacking in most public lodgings. Hotels are usually too big, which disqualifies them from being homey. With their uniformed staff, endless hallways, muzak and that universal hotel smell, they are too impersonal. Yesteryear’s Bed and Breakfasts would often be cosy and home-like, but I always felt like I was staying with someone’s nosy aunt. Airbnbs are usually far too generic with their anonymous proprietors and exterior key boxes, which means that perhaps boutique hotels are the closest one can come to a welcoming home away from home. And that is what we found in Tangier.

Pool at night. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

The city of whispers

It is described as a city of whispers. A place where the past meets the present and poetry lives in the very air you breathe. Much has been written about Tangier, especially by the Beat Generation, a group of writers, poets and artists who lived here in the 1950s and 60s. Though they are all gone, new artists have arrived in their place, ensuring that Tangier still exudes that explorer’s vibe. As for us, we are mere travellers coming here for a long weekend. Yet, we are always enchanted by this city, whose stories are carried by the coastal winds.

Vista Tangier. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The ferry from Tarifa in Southern Spain brings us straight to Tanger Ville port, from where one can easily walk up through the gate of the old city wall and end up in the bustling streets of the Grand Souk. But we have not come here to haggle over carpets or Babouche slippers. We pass the lively sales stalls, the cake sellers balancing their heavy trays, the motorbikes zooming dangerously near lost tourists, and the bars filled with a mostly male coffee-drinking clientele. Soon, we exit at the other side of the Souk, crossing a couple of streets, passing the cemetery on the hill, turning right and left, and we are ‘home’!

La Maison

Entrance. Photo © Karethe Linaae

La Maison de Tanger is like a sophisticated traveller’s refuge, something one senses as one’s eyes meet the generous abode in a classic Moroccan style with that undefinable Tanger twist. There are no glaring hotel signs, merely a brass plaque by the door, enveloped by tropical trees and plants - another surprising thing about this North African coastal city. It is lush. In every tiny gap between buildings, even in the incredibly narrow streets of the Kasbah, you will find towering palms, flowering bushes, and trailing ivy.

Reflections. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

As soon as we ring the bell, the door opens with a familiar Bienvenue! The staff is yet another reason why we love La Maison. All are multilingual Moroccans (Oussama speaks Swedish!) except the ever-helpful French-Canadian manager, Sandra. Today, Zakaria is at the front desk. He and I have been communicating to arrange my interview with the owners so that it won’t coincide with the band’s touring schedules and recording plans. And this weekend, it is about to happen!

Berber walls

Garden room. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

But first, we go to ‘our’ room (one of nine), as we, like almost every guest who returns, want ‘our’ room back. It is just that type of place.

Our special room features a deep crimson ceiling and charcoal walls, accented with original framed art, evoking the ambience of a guest room in a globetrotting, artistically minded friend's home. It is neither among their biggest nor best rooms, which usually face the jungle-like garden with the pool. But since our first stay here, it is as if we belong in this room with the picture of the Arab boy on the wall.

From 'our' room. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Speaking of walls, the entire hotel has a Tadelakt plaster wall finish - a beautiful, more than 2000-year-old Berber technique that leaves the walls smooth as silk yet hard as stone, with subtle colour differences. The choice is no surprise, as the original owners, a French architect and his partner, displayed excellent taste when creating their Maison. The feeling is embedded in the Moroccan hues and the carefully selected textures and pieces of furniture. The garden terraces, where I often bring my laptop to work, and the living room encourage relaxation. At night, the city beckons with its beautiful sunsets, but a date on la Maison’s rooftop is sometimes all one needs to sense the heartbeat of Tanger. As one guest perfectly put it, “La Maison de Tanger is the journey within the journey” (le voyage dans le voyage). Staying here is a journey in itself.

Maroccoan style. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

Only a few other guests are dining with us in the living room this evening. There is no menu, as Ilham, the cook, goes to the market, buys what is fresh and available and serves up a tajin feast that makes our mouths water. And thanks to the new owners, the playlist is chill, and there is wine to be had, which is not a given in this country.

Meet the band

Band at home in Tangier. Photo © Alex Henry Foster Band

The following day, the Canadian owners, Alex Henry Foster Band (formerly Your Favourite Enemies), appear. The band members willingly assist in serving coffee and clearing tables - quite a surprise for what many would describe as rock stars. But then again, they are not your garden variety band. Alex, their visionary leader, has a brief hour for me before it is back to work on two albums coming out later this year. I am curious about how they ended up as hotel owners. However, to understand this, we must start at the beginning.

Alex grew up in a humble family on the east side of Montreal, where they “moved ten times before I was seven”. The one thing the family didn’t lack was music, and in 2006, Alex started the world-renowned band Your Favourite Enemies (YFE).

-We were just a bunch of friends who became professional musicians, touring the world.

Concert photo © Alex Henry Foster Band

Every time they did a show, the band reinvested the proceeds in recording equipment, editing software, and video equipment, eventually becoming completely independent. This is how the church they brought as their home and musical headquarters helped them during Covid, when most musicians “played the ukulele in their bathtubs”. Eventually, the band established their record label, Hopeful Tragedy Records, a merchandising company and even a vinyl pressing plant. But, as Alex points out, the main objective has always been and still is to commune with people.

Band HQ and home in former Montreal church. Photo © Alex Henry Foster Band

YFE’s last album, Between Illness and Migration, became so successful that they could have kept touring forever based on that record. But the hectic life had taken its toll on the band leader, who needed a change. He brought the band to Morocco, where they travelled around for several months. And when Alex was supposed to go to Barcelona to write their next album, he decided to stay in Tangier.

-I just felt I had to be here. I was a bit lost and confused, and just like anyone who is lost and confused, I was probably the last to know. But here in Tangier, I was able to find some balance and perspective.

Alex at La Maison de Tanger. Photo © Karethe Linaae

That was the beginning of their new adventure. What was originally a couple of months ended up being almost two years, during which time Alex grieved the loss of his father and wrote on the roof terrace of the place where he was staying. The band encouraged him to release what he had written, and it became a very personal and intimate record called Window in the Sky.

-Nothing was planned, which is how all the magic happens with me. I didn’t want to be ‘famous’ again, but the album received a lot of attention.

The original six band members were back together, this time as Alex Henry Foster Band, playing what they call “cinematic, Prague-style experimental rock”.

Buying a hotel during a pandemic

Detail. Photo © Karethe Linaae

When the world shut down due to the global pandemic, the band was quarantined in their large recording facility outside Montreal while Alex composed in his home in Virginia. It was also around this time that he started thinking about buying a place in Tangier.

-There is a real spirit here that you don’t find anywhere else.

Friends recommended they look at La Maison de Tanger, which the band viewed via Zoom from their bases in Montreal and Virginia. Between lockdowns, Alex, Jeff and Isabel from the band managed to travel to Morocco to see the hotel in person.

-We walked in and loved it, exclaims Isabel, who has joined the conversation.

In addition to managing their record label, this vibrant Montrealer sings and plays keyboard, flute, clarinet, trumpet, and saxophone with the band.

Isabel Paradis with her sax. Photo © Alex Henry Foster Band

-Thankfully, the hotel had an excellent reputation and staff who helped us from the get-go. As artists, we have very little interest in renting rooms, whereas creating an experience is something we like to do, she explains.

Hospitality was completely new to the band, but they knew how to work with the public and make people feel welcome.

-When we arrived to sign the papers, the owners just gave us the key and said, “You’re in charge now”, and left, recalls Alex.

They immediately needed to regroup. Isabel took the front desk, Jeff, who is a French chef, took the kitchen, and Alex walked around with a glass of wine, talking to the guests.

- It started like that! We had to learn fast, as borders were opening, and we were already fully booked.

Since the hotel was busy, they ended up buying a house in the old Medina, where they established their Moroccan home base, combined with a smaller recording facility. But Isabel admits that being a musician is a very nomadic lifestyle.

-When you are in a band, your identity is just that. It is almost like a marriage. But music is our tool to impact the world and our calling. And if it isn’t music, we try to impact the world positively in some other way - like with a hotel …

Favourite reading corner. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

Part of their small contribution to Tangier is that they can hire local staff and support a little ‘ecosystem’ of families. They like to live like and with the locals, and most of their friends are Moroccan. It might surprise some that the band still has not performed in town, but the band leader prefers it this way.

-I like to be Alex around here. I know how quickly things can change when people see you in a different environment. That is why I never want to mix those two universes.

I am just happy to be the guy who feeds the dogs.

My time is up, and the band is off for other engagements. The final recordings for their upcoming album will be done in their facilities in Montreal before they go touring, once again.

On tour. Photo © Alex Henry Foster Band

We have one more night in La Maison before we head back across the Strait to Spain. But we hope to return to our Tangier ‘home’ soon to spend another evening on the roof terrace listening to the Muezzin’s call to prayer while gazing over the rooftops towards the Mediterranean.

Night. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

5

Like

Published at 5:09 PM Comments (0)

5

Like

Published at 5:09 PM Comments (0)

LA Almazara The World’s First Signature Olive Mill

Thursday, May 8, 2025

Welcome to LA Almazara. Photo © Karethe Linaae

When the international press writes about the Andalusian inland town of Ronda, they almost always talk about the historic bridge or Spain's oldest permanent bullring. Therefore, it was a big surprise when the prestigious American TIME Magazine chose a brand-new building in the Tajo-city as number one on their list of the World's Best Places to Visit in 2025.

Welcome to LA Almazara, the world’s first signature olive mill designed by internationally renowned designer Philippe Starck. The cubic building that towers over the landscape between olive groves has been both highly praised and condemned. But anyone interested in architecture, design, engineering, industry, art, sculpture or agriculture, should visit what Starck himself describes as “an unusual, incredible and miraculous place where visitors can enjoy a powerful experience that challenges and transforms”.

LA Almazara, Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

TIME's annual travel guide, selected by editors and experts from around the world, distinguishes 100 establishments, including hotels, museums, cruise ships, and restaurants, that offer visitors an experience unlike any other. And this year, the number one spot went to the province of Málaga. TIME recognises the completion of a project that has created an authentic ‘cultural revolution’ on the national stage and has brought journalists from around the world to the small city. I had a chance to join their marketing manager, Jorge Amat, and a group of journalists from Madrid and Morocco on a press tour.

Idea from the wine industry

Merging art and industrial design. Photo © LA Almazara

The new demonstration mill facility on LA Organic Olive Farm is located on a 26-hectare property on the outskirts of Ronda, Andalucía. The founders got the idea to create a designer olive oil mill in 2010 after a visit to the Marqués de Riscal signature vineyard in Álava, designed by architect Frank Gehry. The dream of a signature olive mill was born in 2014 with the idea of transferring the concept from wine to olive oil. Since the owners were already producing organic oil and wine at LA Organic with Philippe Starck as partner and designer, Ronda became the natural location. However, it took almost ten years and an investment of over €22 million before LA Almazara could finally open its doors in October 2024.

Between the olive trees. Photo © LA Almazara

“We never thought that the reception would exceed all our expectations when we had the idea of creating the first signature oil mill in the world,” says LA Organics CEO, the young and dynamic Santiago Muguiro, who believes that the initiative could mark a before and after in the Premium olive oil sector.

Building or sculpture?

LA Almazara – building or sculpture? Photo © Karethe Linaae

One cannot avoid noticing the 28-meter-high, 3,000-square-meter rust-coloured monolithic cube that looks as if it has been dropped down from space. LA Almazara, a word of Arabic origin meaning Oil Press in Spanish, is surrounded by ancient oaks and 6,500 olive trees growing organically, without fertilizers or pesticides. Every detail of this avant-garde project is created to be simultaneously functional and provocative - one of Starck's distinguishing characteristics.

The assembly line for olives leads straight into the building. Photo © Karethe Linaae

"It's more art and sculpture than architecture", he says of the project, which fuses Cubism and Brutalism with industrial design. Yet the building's terracotta hue from natural pigments gives it an overall organic feel.

What might be Starck's most unique work combines architectural innovation with Andalusian agricultural traditions. The design also praises the country's matador traditions, with a giant steel bull horn piercing the building's facade. Therefore, I am particularly impressed when Jorge informs us that all the craftsmen involved in the project were local.

Philippe Strack's design detail exterior. Photo © LA Almazara

Each design element has its unique meaning. In addition to the unmistakable horn, the bull’s symbolic ear is shaped like a colossal olive – a tribute to the fruit and the oil. The bull’s mouth – a spectacular terrace with views of the Sierra de Grazalema – is held up by massive freighter chains, a reference to the Phoenicians who were the first seafarers to settle on the coast of Málaga. One might mistake the fourth element as the eye of Málaga artist Pablo Picasso, says Jorge, but like all artists, Picasso was also influenced by the past. His and now LA Almazara’s eye is a copy of the eye that Phoenician seafarers painted on the bows of their boats, both to protect their ships and crews and to deter enemies.

Picasso’s eye has roots back to the Phoenicians. Photo © LA Almazara

In all its artistic splendour, one mustn’t forget that the building has a practical function. Walking towards the entrance, we see the conveyor belt where the olive fruit is brought into the building during the harvest of LA Organics' approximately 80,000 kilos of home-grown olives.

Mill and Museum

LA Almazara interior. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Perhaps the most astonishing thing about LA Almazara is the transformation from being outside to being almost engulfed by the building's magical and semi-dark interior. The entrance takes us through a narrow hall - a visual transformation to the cube’s interior that is as formidable as the outside yet somewhat intimate.

An interior that never ceases to surprise. Photo © La Almazara

“My idea was to show respect for Spain and Andalusia, the most passionate country I have known in my life”, says Starck. He does this, among other things, through a ceiling canvas, painted by his daughter, depicting a woman – the symbol of the country's peasants.

Ceiling art by Ara Starck. Photo © LA Almazara

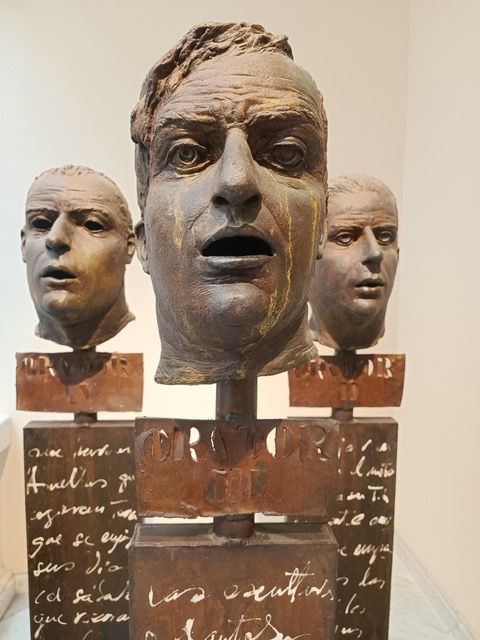

Starck also pays tribute to two locally born heroes, the legendary bullfighter Pedro Romero (1754-1839), and the scientist, inventor and philosopher Abbás Ibn Firnás (810-887 AD). A forerunner of aviation, the latter designed, constructed and tested the world’s first device to fly for several minutes in the year 875, 600 years before Leonardo da Vinci drew his models of aeroplanes and helicopters. Starck’s replica of his ‘hang glider’ now hangs from the ceiling of LA Almazara.

Starck’s replica of Abbás Ibn Firnás (810-887 AD) flying machine. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The oil mill is otherwise fully operational, although only during harvest season when the finest part of the oil production happens here.

Olive mill interior. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The olives follow an enormous pipe that extends through the building to reach the press and oil tanks on the lower level, which can be seen through floor-based glass panels.

Even the mill in the basement has Starck's signature. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Interactive exhibits show the historical uses of oil, from canning to lighting and soap-making to hydraulic car suspension. The museum tour also demonstrates the unique properties of extra virgin oil for health, nutrition and gastronomy. My personal favourite, however, is the theatrical plaza stage opening to the bull's mouth - an unbeatable terrace with a vista of the surrounding mountains.

The plaza. Photo © Karethe Linaae

This is part of Starck's paradox: "It's an enormous material substance, but once you enter, the weight of abstraction gives way to pure emotion."

View from La Almazara, Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

LA Almazara has positioned Ronda as a reference point for avant-garde design with a project honouring the region's agriculture, cultural history and olive traditions. Don’t miss visiting next time you head to La Serranía de Ronda!

LA Almazara amid nature. © Karethe Linaae

4

Like

Published at 5:57 PM Comments (4)

4

Like

Published at 5:57 PM Comments (4)

Who is messing with our time???

Wednesday, April 2, 2025

Spring in Technicolour. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I've never been a conspiracy theorist, but has anyone else noticed that somebody or something is messing with our time?

As a youngster, hearing older people complaining about how fast time passed, I wondered what their problem was since my time felt infinite. But now that I have become one of the ‘oldies’ myself, I couldn’t agree more. I can swear that the Earth is spinning faster and that all universally accepted time segments have been shortened without anyone informing humankind. Forget seconds, minutes, hours and days. A week is nothing anymore because as soon as Monday is over, it’s already Friday. And the year that began a nanosecond ago is already in its second quarter.

Intergalactic movements? Photo © Karethe Linaae

Our age certainly has something to do with our concept of time. For a one-year-old, that year is their lifetime. A child turning five will experience the year as 1/5 of their life, while for someone turning 100, those 365 days will represent 1/100 of their life, so it's no wonder that years feel shorter as we grow older.

Eve. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I do not doubt that the 21st century’s unstoppable technological advances, information flood and endless pressure to perform make our time feel more compressed. There is also more light in our existence, and light - which equals information - increases the feeling of acceleration. At the same time, there is evidence of an acceleration in the Earth’s ‘pulse’ (the so-called Schumann resonance), making time on Earth pass faster. Not to mention the universe’s expansion, the influence of dark matter, the shift of the poles and other forces most cannot even fathom. In other words, this feeling that many of us sense may have a justified reason to be. Furthermore, it may explain why so many people are always in a hurry. Perhaps the body is trying to synchronise with the Earth’s accelerated pulse?

Into space. Photo © Karethe Linaae

What to do? The great Einstein concluded that time is relative, and the only value of time lies in what we do while it passes. So instead of worrying about global acceleration, maybe we should stop and feel April in the air, listen to the birds or talk to each other without finding excuses for why we ‘have’ to run.

Larger than life. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The Spanish have an expression that goes Hay más tiempo que vida, which means that there is more time than there is life. For humans living here and now, time is practically infinite, but as most have realised, our life is not. Therefore, we are better off cherishing our moments and ensuring we follow Einstein’s advice and do worthwhile things while our precious time speeds along.

Just do it! Photo © Karethe Linaae

3

Like

Published at 9:47 AM Comments (2)

3

Like

Published at 9:47 AM Comments (2)

HAMMAM حمّام Andalucía’s Arabic Spa Tradition

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

Photo © Hammam Al Andalus, Córdoba

What we think of as modern spa treatments are far from new. Mankind's attraction to warm water and well-being goes back to antiquity. Both the Greeks and the Romans had very advanced public bathing cultures, but it was the Arabs who perfected it here in Andalucía. One can visit the ruins of these baths from the Al-Andalus era in several places in the region. However, for those who want to step into history with body and soul, why not visit one of the region's many Andalusian Hammam baths?

What is a Hammam?

Photo © Aguas de Ronda

Hammam is a public indoor bath traditionally associated with Islamic communities. The cultural heritage that drew heavily from the classical Roman baths quickly became an institution in Muslim countries in the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia, South-Eastern Europe and Al-Andalus - the Islamic Iberia that covered large parts of Spain and Portugal.

In Islamic cultures, baths had both a religious and a civil function. They met the need for ritual washing and ensured general hygiene long before people elsewhere had running water in their homes. The baths also served a social function and offered a gender-separated meeting place for men and women. Archaeological remains testify to the existence of hammams from the Umayyad period (7th-8th centuries), and in many areas, the importance of the baths has persisted to this day. The hammam culture is still widespread in Morocco, where many Moroccans go to hammams weekly. But Andalucía has not forgotten its Islamic bathing tradition.

Baños Árabes Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The architecture evolved from the original Roman design with large thermae or pools to the use of steam, but they still included a similar sequence - a cold room, hot room, steam room, dressing rooms and rest and reception areas. The heat was produced by wood ovens that supplied hot water and steam, while hot air and smoke were led through pipes under the floor, almost like underfloor heating.

Baños Árabes Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Timeless tradition

Photo © Hammam Al Andalus, Córdoba

Today, this bathing tradition often takes place in beautiful historic buildings that have become places for relaxation and enjoyment. Although the term hammam is frequently used synonymously with baño turco (Turkish bath), my understanding is that hammam uses more steam.

In modern hammams in Andalucía, where both sexes go simultaneously, swimwear is required, while in traditional hammams divided by gender, a loincloth may be enough.

Photo © Hammam Al Andalus, Córdoba

The sequence starts in a lukewarm pool and goes to increasingly hotter and steamier rooms, while we, the Nordic guests, are possibly the only ones tempted by the icy baths. In traditional hammams, one is washed by a male or female assistant (traditionally always the same gender as the visitor) with soap and a powerful scrub before the treatment ends with a rinse with warm water. In Roman and Greek baths, the bathers mostly sat in stagnant water, but in traditional hammams, people were washed with running water, according to the requirement of Islam. Nevertheless, there were several smaller pools in the baths in Al-Andalus, as evidenced by today’s bath ruins.

Try yourself

Before we descend into the balmy comfort of the hammam, I recommend visiting one of the many historical ruins preserved in Andalucía that will explain these baths' historical, social, archaeological, architectural, artistic and aesthetic aspects.

In addition to the Baño de Comares in the Alhambra and the Palacio de Villardompardo in Jaén, one can also visit Los Baños Arabes in Ronda. The latter is the best preserved on the entire Iberian Peninsula, and the museum is in the actual baths, a 15-minute walk from the city centre. Here, you can still go from room to room and see how the baths worked, and if you look more closely at the columns, you discover that they were reused from the city's earlier Roman constructions.

Baños Árabes Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Once one of four hammams in the city, the site was built during the Nasrid period between the 13th and 14th centuries and was conveniently located next to the mosque at one of the three entrances to the heavily fortified city. It was no coincidence that it was located exactly where the river Guadalevin and the stream Arroyo de las Culebras meet because water was essential for its operation. Today, you can see where a donkey pulled a wheel that pumped water to the aqueducts, which, in turn, led to the baths.

Baños Árabes Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

While here, I recommend a stop at Ronda's own Hammam, Aguas de Ronda. The uniqueness of this bath is its location within the old city wall close to the original baths and the subtle design details, such as the finish of the walls in the steam rooms.

Photo © Aguas de Ronda

In contrast to the baths in big Andalusian cities, you can often sit alone in one of the warm baths under a starry sky, surrounded by perfect silence. The baths do not have the same luxury feel as some other baths in the region, but on the other hand, the price is very affordable: €40 per person for the hammam and a 30-minute massage.

Photo © Aguas de Ronda

If you truly want to pamper yourself, the Hammam Al-Andalus in the old town of Córdoba, just around the corner from the mosque and in the heart of the capital of the Umayyad Caliphate, is worth every euro (around €90 per person). This luxurious hammam experience is a close to divine water journey, including a massage with self-selected essential oils or a full scrubbing ritual with dripping soap suds and a rinse on a hot stone block.

Photo © Hammam Al Andalus, Córdoba

Here, you are greeted with soft bathrobes, thick towels and the spa's sandals. All the products are organic and fragrant. In the central room with a large hot pool, one can lie and float looking up at the star-shaped holes in the ceiling, surrounded by Arabic music, flickering candles and a reassuring mist that ensures one never feels overwhelmed by other guests.

Photo © Hammam Al Andalus, Córdoba

Almost invisible helpers remind us to whisper and bring us to our treatments. When not scrubbed or kneaded on the smooth stone block, one can sink into a dozen small baths, enter eucalyptus-scented steam rooms, or sit by the pool and enjoy a cup of exquisite herbal tea or cold spring water.

Photo © Hammam Al Andalus, Córdoba

Hammam is a ritual that intoxicates. While the baths' varying temperatures stimulate blood circulation, the steam works wonders to soften one’s skin, open pores, and cleanse one’s body of impurities. In today's stressful society where everything must go faster, nothing feels better than lying and floating in the weightless warm water in a place where time stops, and the mind is calmed with the exotic scents of this timeless tradition. One can hardly get closer to the Nirvana of the senses.

Photo © Aguas de Ronda

2

Like

Published at 4:08 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 4:08 PM Comments (0)

LA PLAZA - The heart of any Spanish town

Thursday, February 20, 2025

Plaza, Sigüenza, Castilla- La Mancha. Foto © Karethe Linaae

“I’ll meet you at the plaza.”

If you live in Spain, you must have heard these words a million times.

The Spanish word plaza, which has been used in English since the 1830s, comes from the Latin word platea (meaning square or place) and originates from the Ancient Greek word plateîa. It can refer to a space in front of an official building or a church, a permanent or occasional market square or almost any open space between streets and buildings.

Plaza, Málaga. Photo © Karethe Linaae

It is not a park as such, though it often has trees, decorative fountains and benches. Plazas are the heart of any Spanish town or village and the quintessential place for people to gather, where life happens and where one watches life pass by.

Plaza, Montserrat, Barcelona. Photo © Karethe Linaae

When we decided to move to Spain, we fell in love with a small town in the province of Jaén. It was beautiful, it was historic, and had all the things we wanted. But there was one thing lacking – decent plazas. And that became the deciding factor because what is a Spanish town without its many plazas?

Amigos, Plaza, Granada. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I was prompted to write something about this southern European phenomenon because our town hall recently announced that our neighbourhood plaza is about to go through a major renovation. Immediately, we, the neighbours, were on red alert, as we have witnessed what the local government is capable of. Not to mention that our square, Plaza San Francisco, is practically sacred to the local population.

From cemetery to jousting ground to livestock market

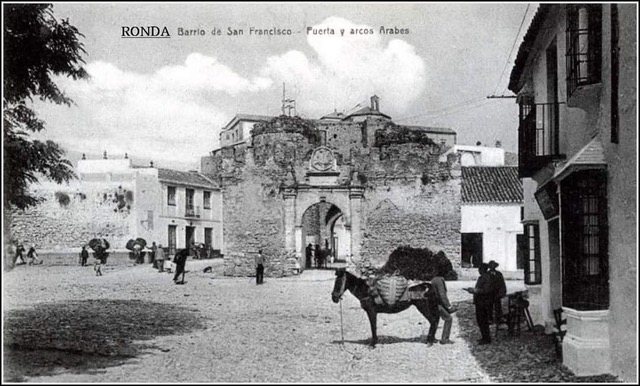

Barrio San Francisco and la plaza. Photo of old postcard

Not only is our plaza ‘sacred’, but it is even named after Saint Francis of Assisi, whose sculpture adorns the central fountain. The Franciscan convent kitty corner to the square also bears his name, and like the plaza, the convent has a long and convoluted history - some true and some, who knows ...

Cherub, La Alameda, Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Despite its Catholic name, the plaza’s history goes much further back. We have of course heard about its Arab past, when our neighbourhood was the local Almocábar (Al- Maqabir), meaning cemetery. Any time anyone digs or does any construction in our barrio, they risk digging up human bones, something we have witnessed time and time again. I asked the local archaeologist, Pilar Delgado Blasco, who confirmed that the tombs in our neighbourhood go back to the Almohad and Nasrid periods, meaning from the 12th to the 15th Century (after 1100 facing Mecca).

Plaza San Francisco, Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

When the town hall recently had the ‘brilliant’ idea of making a modern 7-level, 500-spot parking lot right at the entrance to our historic neighbourhood, the archaeological dig not only unearthed a necropolis with hundreds of Muslim graves but also a Roman burial site dating back 2000 years. "Although 'Romans' appeared in the last excavations, this is the first time Roman graves have been found in Ronda itself", Pilar tells me. Nevertheless, we can safely assume that our neighbours' Roman and Muslim ancestors once strolled across 'our' plaza.

Saint Francis in the snow. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Less official are the stories that the Catholic monarch, Fernando of Aragon, and his troupes practised jousting in the square before the reconquest of Ronda in 1485. Since this was one of three gated entrances in the town’s defensive walls, it is quite likely that the soldiers did some sable-waving to show off to the enemy (though the King probably remained at a safe distance).

Historic document. Archive Photo © Real Maestranza de Caballería de Ronda.

Pilar confirms that there is evidence that the Castilian knights trained in our plaza, however, as far as we know, this happened after the reconquest of the city. “La dehesa, or the pasture where la plaza stands today, was donated to the city so cavalry could carry out various riding exercises and games. It was therefore called Prado de los Caballos or Prado de los Potros", explains Pilar.

Las flamencas. Photo © Karethe Linaae

While I cannot confirm all these stories, one thing we know for certain. As children, our neighbours used to play in the church ruins beside the square during their recreo from school. They often found bones there, and though none of these has been dated as far as we know, our friend Pepe hid a scull in his bedroom that he had dug up in the ruin. (Note to grave diggers: The entrance has now been cemented closed.) According to Pilar, the tombs of the Ermita de Gracia are also from the Al-Aandalus era in Ronda, which was then called Izn-Rand Onda (the fortress city).

Kids playing football in front of the closed-up chapel ruin. Photo © Karethe Linaae

History is always among us in La Plaza. The famous bullfighter Pedro Romero (1754 – 1839), who is credited with inventing the present-day style of bullfighting and who allegedly killed 5558 bulls without being gorged, was born and grew up in a house in front of the square

Ronda is also known for its history of bandoleros – or robbers - in the 18th and 19th centuries. One of the most infamous ones, Pasos Largos, who may have been a bit of a local Robin Hood character, is sure to have crossed our square on his horse.

And speaking of horses, Plaza San Francisco also used to be the site of an annual fair. La Real Feria de Mayo de Ronda is said to be Andalucía's oldest feria de ganadería or livestock and agricultural produce market, which took place in mid-May until the 1990s. It has been taken up again in the last couple of years, albeit with less bleating and neighing.

The rebellious donkey in Plaza San Francisco. Photo © Karethe Linaae

A Norwegian woman who lived here in the 1970s told me that some houses in our neighbourhood still had chickens and donkeys at that time, and one often saw animals running across the square. At that time, the plaza was still covered with sand and soil because today's stone pavement was not laid until the 1980s.

A typical neighbourhood square

Chatting on la Plaza. Old tile. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Today, our plaza is still the heart of our neighbourhood, literally following the locals from cradle to grave.

La mamá, Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

It is just like any typical Spanish plaza - where the barrio’s babies usually take their first wobbly steps, where kids learn to bike, young couples court and families meet on Sunday after Church.

Sharing secrets on la plaza, Jerez de la Frontera. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The plaza is also where the older generations sit and watch life passing by while gossiping about local politics and complaining about their aches and pains. It has been this way forever, and as new generations take over, they too will bring their newborn to the square and eventually end up as an elderly person, reminiscing on a bench.

Couple, Valldemossa, Mallorca. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Plaza San Francisco has all the right components of a good neighbourhood plaza: ancient trees that change colours with the seasons, benches to rest weary bones or catch early spring rays, tapas bars to grab a drink or share a meal with friends, a playground corner with swings for the young and enough space for everyone to stroll around.

Best friends since childhood, Isabel and Mariquiqui. Photo © Karethe Linaae

And this is perhaps the best thing about Spanish plazas. One can sit in solitude and ponder the sky if one likes, but one is never alone because there is always a sense of life unfolding before one.

Plaza, Ourense, Galica. Photo © Karethe Linaae Plaza, Ourense, Galica. Photo © Karethe Linaae

3

Like

Published at 5:51 PM Comments (3)

3

Like

Published at 5:51 PM Comments (3)

The newcomers

Sunday, January 26, 2025

Feeling like an Alien. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Moving to another country can be incredibly exciting. Everything new can be quite intoxicating. You feel fully alive, almost like a child again. An adventurer or perhaps an explorer (although we are far from a Robinson Crusoe in today's convenient jet age).

Pink hot air balloon. Photo © Karethe Linaae

However, an international move can also be challenging, difficult and quite frustrating. The unfamiliar language and culture that seemed so attractive and exotic from the outside, can also be a big barrier, especially professionally.

New moves. Photo © Karethe Linaae

All of us who have immigrated to this country, likely felt a bit lost in the tangled Spanish bureaucracy, not to forget their complicated grammar... I think of the Norwegian trade unionist I interviewed once, who could navigate the Norwegian bureaucracy blindfolded - something he discovered didn't help him one bit here in Spain.

The Gap. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Or the former head librarian who went from speaking fluent Norwegian and English to having to learn basic Spanish expressions like a first grader.

A new language. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Some skills must be learned all over again - like when my husband and I, aged 65 and 49, had to go back to Spanish driving school with a bunch of 18-year-olds. Nor is all professional knowledge equally transferable, especially across national borders and cultural barriers.

Foreign tongues. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I recently interviewed a man who experienced exactly this. He had come to Costa del Sol from Los Angeles with extensive experience in communications and administration for professional American sports teams. Understandably, he was quite confident about his instant success in Spain. But the landing was not entirely soft and far from as easy as he had expected.

Dalí expressed it perhaps the best. From his exhibition in Figueres. Photo. © Karethe Linaae

Fortunately, he did not give up and today he is the international communications manager for a professional Spanish sports team.

I, for one, could easily relate to his story. Like him, I came from North America. I had years of experience in the film industry, I'd had a film in Cannes and been nominated for the Canadian Academy Awards. But that meant nothing when we got to our small Andalusian village where we didn't know a soul.

Culture lessons. Photo © Karethe Linaae

What good did half a dozen languages do me when none were Spanish? And what help was my master's degrees in a neighbourhood where some of the very oldest residents could hardly read or write?

To the locals, we were just another couple of new foreign faces. It was as if our past had been wiped clean.

Just another neighbour. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Settling in another country forces us out of our comfort zone. It can be humbling but also very liberating.

Like the LA sports administrator, I had no idea what I would end up doing when I got here - that I would co-found a local environmental NGO just months after we arrived with our five suitcases, that a year later, I would be standing in front of a class of out-of-control Spanish 3-5-year-olds that I one way or another was to teach English to, that I would write a book and get it published in the United States and then Spain, that we would grow our organic vegetables right down in the valley or that I would end up working in my native language as an editor - in Andalucía.

Do what you love, and love what you do. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Who knows what tomorrow will bring? My motto is the tried and tested Carpe Diem. I am open to what may come and excited to embrace the next chapter of our Andalusian journey.

Life with new eyes. Photo © Karethe Linaae

4

Like

Published at 10:16 AM Comments (3)

4

Like

Published at 10:16 AM Comments (3)

The hourglass

Friday, December 27, 2024

Lonesome. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Every month, a small group of art- and history buffs meet in an esteemed library in Ronda, Andalucía to hear a Spanish philosopher talk about anything between heaven and earth. It can be a book, a piece of music, a painting, or some random object he chooses to elucidate – because that’s what philosophers do. They philosophize. This time, the chosen theme was hourglasses.

Why an hourglass, one might ask?

Hourglass. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Human beings have always had a certain understanding of the passage of time. The Neanderthals followed the day from sunrise to sunset and probably were more familiar with the journey from cradle to grave than we are today. The first man-made timekeeper we know of - the sundial – was invented around 1500 BC. At the time, it was believed that the Sun revolved around the Earth every 24 hours. It took 3,000 years before Copernicus clarified that the Earth moves around the Sun and rotates on its axis. It was also around the time, that the hourglass was invented. Since it could only measure limited time segments, it lost its practical purpose as soon as better timepieces were invented. However, the hourglass took on an important symbolic role, especially in Fine Arts, where they represented the finiteness of life. In historical paintings, the hourglass is commonly held by a skeleton.

A clearer reminder should not be needed…

Religious art, Osuna. Photo © Karethe Linaae

As we enter a new year, our thoughts inevitably turn to times gone by and the time to come. Time is often described as twofold: objective time (clock time) and subjective time or how time is experienced by the individual. Consider the difference between an endless hour spent waiting at the dentist’s office compared to how furiously fast an hour passes when watching an exciting thriller.

It can feel like our time (like the sand in the hourglass) speeds up as we age or move towards the 22. Century. Simultaneously, we have become excessively time-obsessed, so much so that the clock seems to control us - not vice versa. Many of us tend to focus on and talk endlessly about what we don’t have time to do: exercise, learn Swahili, read books or make Sourdough bread.

Falling. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Everything we do is a choice. And no matter what we do with our time, the sand keeps falling in our hourglass. Although I promised myself not to make any New Year’s resolutions this year, my resolute plan is not to focus on what I (think) I don’t have time for, but to contemplate all the wonderful things and journeys I wish to spend my precious time on.

2025 is here. Be sure to sit comfortably, enjoying the remaining sand, not just obsessing about the sand that ceaselessly disappears down your hourglass.

Mathilde’s happy feet. Photo © Karethe Linaae

2

Like

Published at 6:01 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 6:01 PM Comments (0)

ONCE - Far more than an organization for the blind

Wednesday, December 18, 2024

“We are the imprint we leave behind” Text on the T-shirts for ONCE’s annual inclusive race. Photo © ONCE Ronda

Everyone in Spain has probably seen the lottery kiosks with the sign ONCE in capital letters. Many know these are run by the Spanish National Organization for the Blind or Organización Nacional de Ciegos Españoles (ONCE). But what most people don't know is that Grupo Social ONCE is much more than an aid organization for the visually impaired. It is also the world's largest employer of people with disabilities!

To get better acquainted with the organization, I arranged to meet with the managing director of one of their ten district offices in the Málaga province, as well as one of the organization's over 71,000 affiliate members and one of the 20,000 salespeople one meets on the streets, squares, and in the ONCE kiosks around the country. I came out of the meetings with an enormous respect for what they have accomplished and continue to accomplish. After you have read this article, I hope you also will buy ONCE lotto tickets - not to win, but to help this remarkable organization.

From User to Executive Director- Francisco Javier Gómez Molina (37)

Francisco Javier Gómez Molina. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Javi’s story

Francisco Javier, or Javi as his friends and colleagues call him, was completely blind when he was born. When he was one year old, his parents registered him as an affiliate member of ONCE in his hometown of Vélez-Málaga, so that he could receive the assistance and materials he needed to study on an equal footing with other students. After primary and secondary school, Javi studied law in Málaga and Paris and became a lawyer.

-I was teaching before Covid, but it was impossible to continue during the pandemic. It gave me time to reflect, and I decided that if I didn't return to the workforce, who knew when it would happen? I started selling lottery tickets for ONCE in February 2021. It was a completely new experience, but everything you learn professionally and personally can be useful.

Two years later, in February 2023, ONCE hired Javi as executive director of the 80 employees and the approximately 130 affiliate members of the district office serving Ronda and 30 villages in La Serranía de Ronda.

- ONCE has shaped my life, all the way from when I received help as a child. Through my work, I have become even more involved in the organization by executing the services that help our members.

Javi outside the office. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Unique in the world

Organización Nacional de Ciegos Españoles (ONCE) was founded on December 13. 1938 by a group of smaller associations for the blind whose members didn’t want to be dependent on alms and charity. The first lottery was drawn on May 8. 1939, and the objective continues to be the same to this day - to include the blind and visually impaired in society via something as simple as lottery sales.

- ONCE has grown enormously from the first three-digit lotto tickets to all the different lotteries we have today. The organizational model makes us unique in the world. We are an independent, not-for-profit organization financed exclusively through lottery ticket sales. Everything happens with the knowledge and consent of the Spanish government, and all the sellers are employed and part of the Spanish social security system. ONCE commercializes safe, social, and responsible games with external verifications that guarantee the legality and transparency of the lotteries. All income from the sales that do not go to salaries and prizes is reinvested in the organization's social work.

Some of ONCE's 80 lotto sellers in Serranía de Ronda. Photo © ONCE Ronda

Today, they have 135 district offices coordinated from the headquarters in Madrid. ONCE has created various foundations that provide training, equipment and help with job training and employment for the disabled, a foundation for the deafblind, a mutual aid foundation for the blind in Latin America, a guide dog foundation, and this year, they launched a foundation for people with low vision.

-Our affiliates can be 100 % blind, have a severe visual impairment, or have other disabilities. The organization’s assistance ranges from psychological help, social workers, and rehab technicians to services for guide dogs and training using computers with special screens. At the same time, people with other types of disabilities or people who have been disabled due to work accidents and need help getting used to their new living situation can turn to the organization in search of employment.

Fra glass cutter to a white cane - Juan Jesús Barragán Jiménez (68)

Juan Jesús Barragán Jiménez. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Juan’s story

Juan worked as a glass cutter until he began losing sight some 20 years ago. While he could still make out letters, he took a braille course. Today, Juan is completely blind (3% vision) and moves around town with his white cane. He took up his braille studies recently and continues to study as an affiliate member of ONCE.

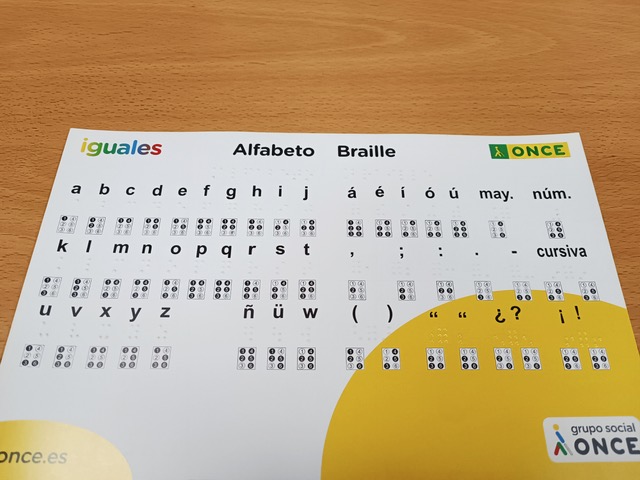

- Braille is a writing system with two parallel vertical lines and three dots, a combination of which all letters, numbers, and punctuations are written. Our course takes place every 15 days, and we have texts that we must prepare at home and then read aloud to the class. At first, it's difficult, but as you get used to the system, it gets easier.

Braille alphabet by ONCE. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Juan says he is lucky because he could see before he went blind. In his job, he knew every street in the city, and this helps him now because he can visualize where he needs to go. But he admits that all the tourists downtown make it "very, very, very difficult" for him.

- It is impossible for me to walk down the main street without a companion. I also need help to cross the bridge, and if I go alone, I usually end up in an argument. Most people rush about and don't look around. Some are kind and take me by the arm and follow me across the bridge, but others don't even move aside. If they complain because I am 'in their way', I say: You can see. I can't!

ONCE has taught Juan how to walk with his cane on the street and helped him with his mobile phone. If he has problems, he can call a specialist technician for the blind.

- They’ll come and help you at home, but you must be prepared to wait. They may only come once a month because they serve so many places. I would love to take a computer course with ONCE, but there are never enough students to get a teacher. Ronda is a small town, so if you want to learn computer skills for the blind, you must go to Málaga where they offer all the different courses.

Who are the ONCE sellers?

Some of ONCE’s lottery ticket sellers. Photo © ONCE Ronda

ONCE has always tried to be inclusive, Javi explains from the ONCE office.

- We work for inclusion in society at all levels, inside and outside the organization. ONCE has over 20,000 sellers in Spain today, but I wish we were even more so that more disabled people who are unemployed today could support themselves and their families.

ONCE's lottery sellers receive minimum wage plus commissions and have statutory days off and regular holidays, but as Javi points out, they receive much more.

- We look after our employees and seek stability for them and their families. Perhaps they have been unemployed for several years and get the satisfaction of being able to contribute, have financial stability, and bring money home to their families again. But it is not just about financial, and practical help. Our goal is that our employees no longer must live with uncertainty, which means less stress and fear and a better sense of self.

ONCE brings members to visit Parauta, including Juan, his wife Inés, and Javi. Photo © ONCE Ronda.

To work for ONCE, the applicants must be at least 33.3 % disabled, as required by the Spanish social security system. If there is no medical reason that prevents them, blind, severely visually impaired, other disabled, and those unable to work due to an accident can apply for a job with ONCE. In addition to the health requirements, the applicant must partake in ONCE's training and exams. After passing a six-month trial and two annual renewals, they get a permanent position.

The sellers have their fixed places where they sell tickets and are responsible for returning unsold tickets drawn the same evening so that the system does not register the tickets as outstanding or still in play.

ONCE’s face on the street - Lottery seller Ana María López Valiente (49)

“ONCE would never have existed had it not been for the sellers." Ana María López Valiente. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Ana’s story

When Ana was two years old, she fell on the playground and hit her head. The doctor said there was nothing to worry about, but eight months later, Ana woke up one day unable to walk or stand on her legs. Until she was 15, she had to go to Málaga for weekly treatments, but it was the wife of a traumatologist who finally got her walking again. Twenty years later, Ana was a newly divorced single mother with an 11-year-old daughter, and her €300 in monthly disability benefits from the Junta de Andalucía wasn’t even enough for food. ONCE gave her a chance. Today Ana has worked with them for 14 years and is a mentor and instructor for the organization.

- I have been disabled since I was a child, but nothing is difficult for me. I have never had problems or complexes. I've done what I could and that's it. Until my teens, I had a special boot and a metal brace on my leg. Some kids at school laughed at me and said, "Here comes the cripple", but I just ignored them. I was lucky to have good teachers who made the other students stop bullying me. When I became a mother myself and got divorced, I wondered how on earth I was going to cope. A friend recommended ONCE, but my parents didn’t want me to lose my disability benefits. Now they bless the day when I started working for ONCE ...

Ana never studied nursing as she dreamed of as a child, but with her permanent job, she is not only independent, but can help her family. And she also found love via ONCE!

- The Madrid head office selected me as a mentor to teach future salespeople and evaluate their suitability for the job. My boyfriend Pedro was one of my students. I had never taught a blind person before, so I had to get complete training. We worked together for three or four months before we became a couple, and later I moved in with him. He helps me at home, and I help him at work. Today, there are many aids for the blind such as kitchen appliances with braille. I would love to take a braille course. ONCE also offers English, IT and management courses. If I wanted to, I could study to become an administrator, but I'm happy where I am.

Ana has many loyal customers and when she is not at her regular corner, they call her and ask where she is.

- When I was new to the job, I had to invent something to increase my sales, so I dressed up. Now, it has become a tradition. Every celebration - Christmas, Carnival, Ronda Romántica, pride days, Black Friday, and Halloween - I dress up and if I'm not, my customers wonder what’s wrong!

Ana dressed up for Halloween, 11.11 and Feria de Ronda. Photo © Ana López

Through her work, Ana has become an expert on people since customers often tell her their problems.

-Many people have a hard time making ends meet, but almost everyone can buy a lottery ticket for a couple of euros, which gives them hope. The biggest prize I ever gave out was €20,000. But the best was when I gave a prize to a customer who said I had saved his life. He explained that he had no money for the dentist, but with the €600 he had won, he could pay his bill.

For once, it's not just me, the journalist, asking questions. Ana also wants to 'test' me.

- I have a question for you. How do blind sellers distinguish one note from another?

-By feel???

- They stick the note between two fingers. By the size, they know whether it is €5, €10, or €20-note. They identify coins by their thickness and edge. A blind seller can distinguish between all our lotto coupons and know the expiry date because the coupons are embossed with the day and date.

Although it may seem like some ticket sellers don't have any health problems, they always do. Ana e has a colleague who is going blind due to diabetes and others with spinal cord- or heart problems, ailments that outsiders cannot necessarily detect.

- ONCE is an organization that changes lives. Many sellers have thought “If I don't get a job with ONCE, who else will hire me?” We are a team that supports each other. We have safe, stable, and dignified work. Few jobs are so ideal!

Ana at work. Photo © Karethe Linaae

3

Like

Published at 7:51 PM Comments (3)

3

Like

Published at 7:51 PM Comments (3)

How I came to love November

Tuesday, November 5, 2024

Foggy landscape. Photo © Karethe Linaae

They say that when it rains, it pours, and that can certainly apply to Spain. After several years of intense drought, all the precipitation we should have had during the last 12 months came in a single night or just a few hours. The tragedies and destruction, especially in Valencia, are unfathomable. As I write this, rescuers are still searching for the missing, while the cleanup and rebuilding will take years. So, what can we do? Light a candle, donate blankets, brooms, first aid kits and money, and be as prepared as possible for when (as it is no longer a question of if) tragedy strikes again.

Jailed seaweed art. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Whether we like it or not, November is here, and if you, like me, come from the north, you probably grew up hating it. As a youngster in Norway in the 1970s, we thought it was the most dreadful month of the year. It was dark and gloomy and cold and wet. The days fluctuated between snow, slush, freezing rain, deadly black ice and more snow. November was the month when nothing happened that was worth living for. Halloween was not yet 'invented' (If I recall right, it only came to Norway in the 1990s). Nobody had heard of Black Fridays and Cyber Mondays, and the decorations for December’s many festivities - Advent, Santa Lucia, Jul (Xmas) and New Year - were still in boxes in the attic. November was a month we wished we could skip over. The mere mention of it made us want to go to bed on the 1st and hide under our down comforters until the 31st, sleeping through the entire thing!

Frozen leaves. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Now in the so-called autumn of my life, I see November in an entirely different light. It has been years since I looked forward to Christmas as such. Instead, I look forward to every day, especially fall days. Perhaps it comes from living in rural Andalucía where the sun rarely stops shining, but now I find myself longing for that special November mood.

Forest. Photo © Karethe Linaae

As I spend a few days in my native land, I cherish the foggy mornings, the mist-filled air, the sudden crescendo of the wind and the dancing leaves. A more subtle colour palette replaces the bright fall colours, showing barren trees against an ever-changing sky.

Sky. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I treasure the soft golden afternoon light, the threatening clouds and the surprisingly early hour of dusk. I delight in the iridescent green moss that suddenly appears among the soothing earth tones and grey hues of the latter year and the forgiving feel of walking on the leaf-covered ground, helping nature withstand another winter.

Fall ground cover. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Late fall brings a whole new understanding of the Scandinavian concept of cosiness. A warm blanket, flickering live candles, a steaming cup of hot tea, the smell of a wood-burning fire, comfort food in the oven, aged wine, woollen socks, nature walks dressed to the gills and simply being at home. That is, for those who are lucky enough to have a home, something one should never take for granted.

At home. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Global warming has changed the Novembers of my childhood, although it still offers gale-force winds, sleet and unimaginable whiteouts. These days, I value the so-called ‘bad’ weather of the season, whether I admire it from behind a windowpane or immerse myself in it. Barring recent weather tragedies, there is something cathartic about foul weather: high winds with feisty waves and seaweed slung far ashore, thunder and lightning, torrential downpours and drifting sheets of snow.

Calm before the storm. Photo © Karethe Linaae

In my latter life, I see the beauty of the fall season through different eyes and am thankful for all the November-ness that it brings. I hope this month won’t be remembered for all the suffering but as a November of solidarity, generosity and compassion.

Candle in the wind. Photo © Karethe Linaae

2

Like

Published at 7:30 AM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 7:30 AM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|