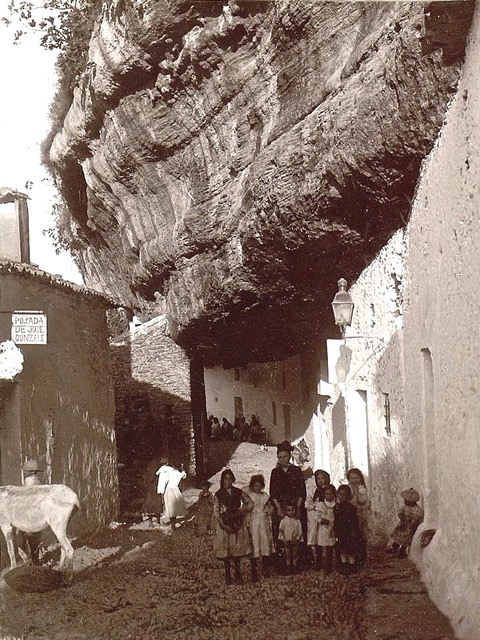

Envisage a town concealed in a gorge with houses dug into a mountainside. A place virtually unknown to tourists a few years back, yet where history goes back millennia. Now this has to be an interesting town to visit…

Meet Setenil de las Bodegas - a tiny municipality in the province of Cádiz with a mere 3000 inhabitants. In 2018, Setenil was included in the Association of Spain’s Most Beautiful Villages. Only last month it was also chosen as the Best Secret Destination in Europe, ahead of Malcine in Italy, Renania in Germany, Agos Nikolaos in Greece and other lesser known European jewels.

Meet Setenil de las Bodegas - a tiny municipality in the province of Cádiz with a mere 3000 inhabitants. In 2018, Setenil was included in the Association of Spain’s Most Beautiful Villages. Only last month it was also chosen as the Best Secret Destination in Europe, ahead of Malcine in Italy, Renania in Germany, Agos Nikolaos in Greece and other lesser known European jewels.

Setenil forms part of the route of Andalucía’s White Villages, yet the town has something which none of the other Pueblos Blancos possess. Whereas most white villages are situated on high ground, Setenil is embedded into a narrow river gorge. Approaching from the mountain plateau that surrounds it, you cannot see any sign of an upcoming town. Like Alberta’s Badlands, the road suddenly dips into a crevice, in Setenil’s case created by the Río Trejo and Río Guadalporcún.

Setenil’s most distinctive feature however, is the town’s large number of cave dwellings. The white washed buildings literally seem to grow out of the mountain or to be physically embedded in the rockface. Many homes have a single external wall. The rest of the living quarters will expand underneath the protruding overhang, dug out of the porous sand stone by enlarging the natural caves that the river created millions of years ago. This innovative design makes Setenil one of the most original villages not only in Spain, but in all of Europe.

Troglodyte living is not a new thing in Setenil. Caves in nearby regions were occupied in both Paleolithic and Neolithic times. It is likely that Setenil also was home to our Neanderthal ancestors, but evidence of Stone Age residents may have been lost in the spring-cleanings of newer inhabitants during the last couple of millennia.

The town’s name is said to have come from the Latin words septem nihil (seven times nothing), referring to how this Moorish town resisted the Catholic Reconquista army, only falling after seven long sieges in 1484. In my opinion there has to be another explanation. Firstly, how would the Latin speaking Romans have known about a conquest that happened several centuries into the future, after they left the Iberian continent? Secondly, would a Latin town name have been used through 700 years of Moorish rule? And finally, would the Catholic Monarchs want to name the town in memory of their six unsuccessful attempts of taking over the town, even if they finally succeeded on the seventh attempt? To me, it is a mystery indeed.

The addition to the name, de las Bodegas, dates from the 15th Century, and refers to the once thriving local wineries. After expelling the Muslims, Setenil’s new Christian settlers introduced grapevines, while continuing the Arab olive and almond production. The vineyards were wiped out by an insect infestation that killed virtually all of Europe’s grape stock in the 1880’s, but recent replanting has once again filled up Setenil’s bodegas for us to enjoy their bounty.

While Setenil is a mere pueblo today, it was once an important town. In fact it received a Letter of Privilege from the Catholic Monarchs in 1501, giving it trade benefits on level with Sevilla. Yet the true sign of the town’s past importance comes in the form of an engraving from 1564, when Joris Hoefnagel drew an atlas of Europe’s most important towns, one of which was Setenil! His Civitates Orbis Terrarum, published in Cologne in 1572, was one of Europe’s first map books.

Living merely 30 minutes drive away, Setenil is a favourite place for my husband and I to take visitors. You can see the entire town in a morning, though I believe one should never miss the chance of having lunch under a suspended rock! If you come on a Friday, you get the added bonus of seeing the villagers descend upon the weekly mercadillo (8 - 14ish) It is great for people watching and a must if you are in the market for flowers, fruit, spices, synthetic dresses or granny style underwear.

We prefer less busy days, when we can spend an hour or two doing the natural circuit, strolling along one side of the river and returning on the other. Wandering the streets of Setenil, or callejear as they call it is simply a joy. Everywhere you look there are magical corners, narrow alleys and picturesque balconies bursting with flowers.

Our walk usually starts in Calle Cuevas de la Sombra (loosely translated as ‘the shady cave street’), one of the most astonishing rock-ceilinged streets in the known universe. In spite of the limited headroom, locals blast through in their mini-trucks not paying the slightest attention to the tight clearance on either side.

There seem to have been a recent revival of the town, with an increasing number of stores and delis. We stop in one of these to have a chat with the owner about village life. La Cueva del Ibérico, like many shops in town, is really a cave. There is no ceiling as such, just the bare rock overhead extending onto the back wall. Not only is the atmosphere of the store fabulous, but Daniel the proprietor knows his trade. He can tell you where every cheese is produced and why one wine differs from another, and those who are lucky to spend the night or not driving can always ask for taste.

Daniel was brought up in Setenil, but like many young, left town to study and make a career in the big city. As a husband and recent father, he has returned. He likes the slow pace of Setenil, but also the year-round visitors from all over the world. He tells us that five years back there were only a handful of guesthouses in town, while today there are more than 30 casas rurales, including half a dozen within spitting distance of his shop.

We emerge from Daniel’s cave with a litre of sherry after having tried the whole range - from the driest Fino and the floral Amontillado to the sweetest Pedro Ximénez grapes. At the end of the street, after a short but steep climb (not recommended in the hot midday sun), we stop at a local chapel to light a candle by one of the many statues of the Virgin Mary.

Continuing uphill we come to Plaza de Andalucía. It is a little early to begin to tapear, so we indulge in our first iced coffee instead. The square has a couple of tapas bars, as well as possibly the world’s only cave bank!

Meandering our way up past the tourist office we arrive at the top of the bluff, which offers an excellent vantage point of the town. The Torreón del Homenaje tower is the only remains of the original alcázar castle from the 12. Century. Occasionally used for art exhibits, it is also well worth the climb to the top for an undisturbed birds’ eye view of the surrounding countryside.

Descending through narrow alleys with kissing-distance from the buildings on one side to the other, we return to river level. We are ready to explore the town’s less frequented roads, where some of the most charming and authentic cave homes in Setenil can be found.

The sandstone overhangs make natural turbans for the cave dwellings, which merge perfectly with the overgrown terracotta roof tiles.

These traditional rural homes have few and small windows, to keep the heat out in summer and the cold out in winter. One has to ask oneself how living in such enclosed stone quarters must be in the rainy season, as even on the sunniest of days the buildings feel humid and cool. Not sure if I would like to try, but I can see it being perfect for curing chorizos…

Not all the caves are homes though. Some are converted into unsightly garages, while others look more like squat barns and donkey shacks. The majority of these cave dwellings were probably shared by people and their domestic animals way back when. Maybe some still are?

We return on the opposite side of the river, walking along Calle Cuevas del Sol (sunny cave street), which is without doubt the most frequently photographed street in town.

The market stalls are being disassembled into vans, and we find a table at Bar Frasquito where Pedro and his family serve to-die-for tapas. My weakness is their fried slices of eggplant with melted goat cheese topped with a Pedro Ximenez reduction - a true hedonistic treat. As an aside, the English translations of Spanish menus can be quite amusing, often spelled phonetically, translated literally, or just plain wrong. My eggplant with goat cheese for instance, is written up as Eggpland wiht good chesse.

Setenil has managed to reinvent itself in the 21st Century, while retaining its charming village feel. People still practice traditional agriculture, combined with a growing but limited tourist trade. Add to this a unique setting and beautiful surroundings and you get a rural community with an authentic Andalusian flavour.

One thing is for certain. Setenil is truly unforgettable, and if you ever doubt it, all you have to do is look up…