My friend Odd Steffen has died. It is a shock. He was wise and solid. I’d expected him to always be there.

I’ve been remembering all the good times we spent together. A big research conference in Birmingham: his plane was late, we were all panicking. Then he strolled in, calm as you like, just in time to deliver his presentation. Dinner in a Blues bar in Chicago. And a weekend in Ville’s woodland retreat on the south-west coast of Finland. It was June, daylight lasted for ever. Sunshine, sauna, swimming, Sibelius, sailing.

I’ve been remembering all the good times we spent together. A big research conference in Birmingham: his plane was late, we were all panicking. Then he strolled in, calm as you like, just in time to deliver his presentation. Dinner in a Blues bar in Chicago. And a weekend in Ville’s woodland retreat on the south-west coast of Finland. It was June, daylight lasted for ever. Sunshine, sauna, swimming, Sibelius, sailing.

Memories matter. When life is difficult or sad, we can draw on memories of good times. They help us to get through the troubled present, and nourish the hope that good times will return.

Memories do more than that. They give us an awareness of continuity. They build our sense of coherence, our identity, our ideas about who we are and where we belong.

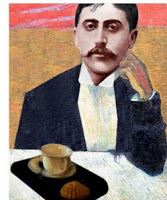

Proust was a delicate creature, who spent most of his adult life in sealed room in Paris, in a state of severe health anxiety. He was also a wonderful writer. He has important things to say about memory and continuity. Tiny, apparently insignificant events – a cake crumbled into a cup of tea, catching sight of a church tower, the smell of mildew – can be triggers that recall lost times, bringing them together with the present in a continuous reality.

Proust was a delicate creature, who spent most of his adult life in sealed room in Paris, in a state of severe health anxiety. He was also a wonderful writer. He has important things to say about memory and continuity. Tiny, apparently insignificant events – a cake crumbled into a cup of tea, catching sight of a church tower, the smell of mildew – can be triggers that recall lost times, bringing them together with the present in a continuous reality.

Memories keep us connected with our past, with where we have come from in this unique life we are leading. These connections help us survive and flourish, and build for the future.

‘That’s all very well’ I hear you say, ‘if you’ve got a store of good memories to fall back on. But what if my memories are mainly bad ones?’

Sometimes memories can be cruel. The Russian writer Dostoevsky was haunted for years by the memory of the moment when he stood before the firing squad waiting his call for execution, before his reprieve was suddenly announced. Many people who suffer trauma in childhood find dark memories returning to haunt their lives and thoughts. Or maybe your memories are of failures, unrealised dreams, of things that might have been.

Fortunately, memories are not fixed. We can change them.

We can turn memories into sources of energy and hope. We can draw new implications from old memories, or expand them by adding in the experiences of others.

In his Intimate History of Humanity, Theodore Zeldin tells of his friend Olga who used her fearful memories of life as a political dissident as a stimulus to change – given the opportunities provided by glasnost and perestroika – into a life as a commercial statistician. This gives her financial security and the freedom to dress well, travel frequently and indulge her passion for Proust.

And there is Quoyle in The Shipping News. His earliest memory is being a disappointment to his father, because he almost drowned when he was supposed to learn to doggy-paddle. He grows up as a fat, lonely loser. But new experiences of friendship, creativity and love alter his awareness of the past. His memories expand, enriching his past and his imagined future.

And there is Quoyle in The Shipping News. His earliest memory is being a disappointment to his father, because he almost drowned when he was supposed to learn to doggy-paddle. He grows up as a fat, lonely loser. But new experiences of friendship, creativity and love alter his awareness of the past. His memories expand, enriching his past and his imagined future.

He remembers how he saved a bird his daughter had found, and how thrilled she was.

‘If a bird with a broken neck could fly away’, he wonders, ‘what else might be possible? It may be that love sometimes occurs without pain and misery.’

What about you? What memories keep you going through bad times? What helps you increase your supply of good memories?