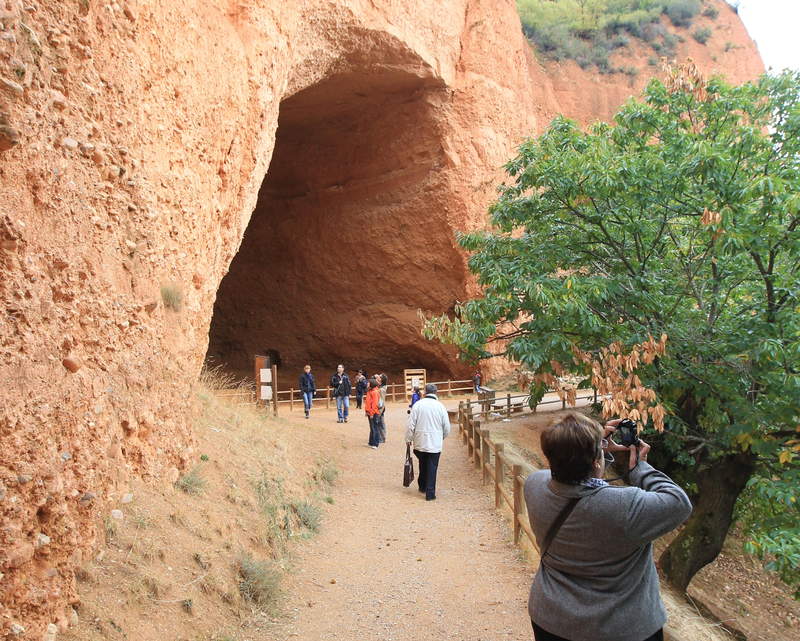

In the region of Bierzo in the province of Leon, lies an unusual man-made landscape called “Las Medulas”. In the 1st century A.D. the Roman Imperial authorities began to exploit the gold deposits of this region in northwest Spain, using a technique based on hydraulic power. After two centuries of working the deposits, the Romans withdrew, leaving a devastated landscape. Since there was no subsequent industrial activity, the dramatic traces of this remarkable ancient technology are visible everywhere as sheer faces in the mountainsides and the vast areas of tailings are now used for agriculture.

Las Médulas gold-mining area is an outstanding example of innovative Roman technology, in which all the elements of the ancient landscape, both industrial and domestic, have survived to an exceptional degree. It provides exceptional evidence of a tradition of working and the technological and scientific exploitation of nature in a vanished civilization, which resulted in significant use of applied hydraulics. What is visible today is a unique cultural landscape, shaped by drastic human intervention and natural processes, with in addition the introduction of non-native flora, which has survived since the Roman period without change.

The placer (alluvial) gold deposits of the Las Médulas region were being exploited on a small scale in the late Iron Age. Evidence for this is largely circumstantial, based on excavations of the defended sites (castros ) of the region and the related cemeteries, with their wealth of golden objects.

The north-western part of the Iberian Peninsula was the last to be conquered by the Romans, after the campaign of Augustus in 29-19 BC. Some Roman urban centres were founded and a characteristic Roman road system built, but the indigenous population, although considerably reduced, continued to live on its tribal territories, around its typical defended hill forts for a considerable time.

However, from the second half of the 1st century AD new settlements on the Roman model were set up, with the objective of exploiting the rich mineral resources (notably gold, but also iron) of the region. At the same time, new techniques of extracting the gold were put into practice, on an infinitely larger scale than in the pre-Roman period. Under the Roman system, all mineral resources in imperial provinces were vested directly in the emperor. The mining areas formed part of the province of Hispania Citerior, which included the northwestern military regions of Asturia and Callaeciae, and were declared to be imperial estates. Contrary to general belief and unlike the situation in other imperial gold-mining areas (such as Wales), the workers in the mines were free men, not slaves. Their settlements can be found all over the region, alongside yet clearly distinguishable from those, which housed the imperial officials and their staffs. Engineering activities, such as the major hydraulic works of building dams and cutting channels and road construction, were the responsibility of the Roman army. The military presence was also maintained to keep the peace and to ensure the safety of imperial officials and their deliveries of gold to provincial capitals and over the sea to Rome. Sweeping changes took place in the Roman monetary system in the 2nd century AD: Caracalla restored the aureus to its former place, and as a result the Spanish mines reactivated their production.

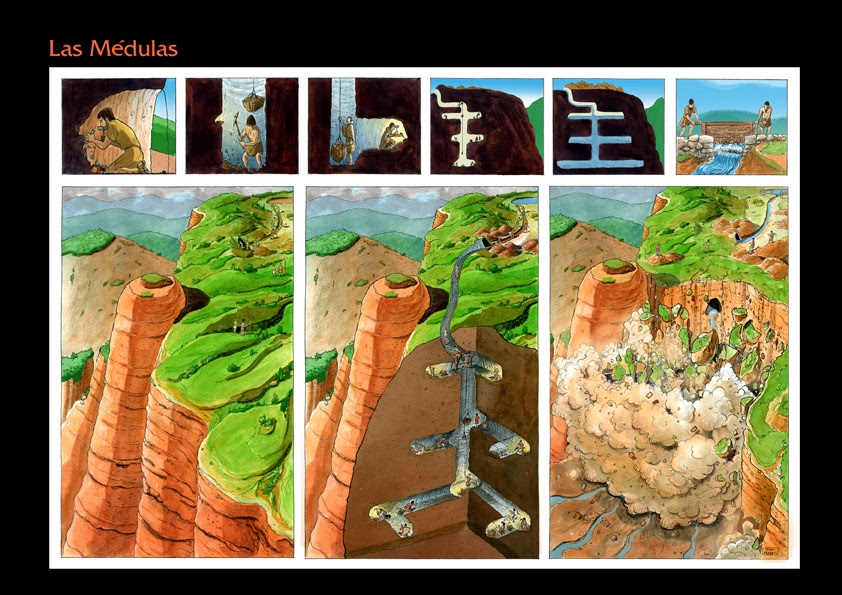

The Archaeological Zone of Las Médulas comprises the mines themselves and also large areas where the tailings resulting from the process were deposited. Within the area there are dams used to collect the vast amounts of water needed for the mining process and the intricate canals by means of which the water was conveyed to the mines. Human settlement is represented by villages, of both the indigenous inhabitants and the imperial administrative and support personnel. The area contains the route of one major Roman road and a large number of minor routes, used within the mining operations: water from springs, rain, and melting snow was collected in large reservoirs, which led by a system of well built gravity canals to the mines themselves, over long distances. Galleries were cut into the sterile strata many metres deep that overlay the layers of auriferous conglomerate. When the sluices of the dams were opened, enormous quantities of water flowed into the galleries, which were closed at their ends. The pressure, which built up, caused the rock to explode and to be washed away by the water flow forming enormous areas of tailings, several kilometres in length. The process is vividly apparent on the working face at the main Las Médulas site. The operating face of this spectacular form of mining slowly moved across the landscape. The system of water canals and conduits has been traced over large areas of the site, and measures at least 100 km.

Sweeping changes took place in the Roman monetary system in the later 2nd century AD, when the gold aureus was devalued, with catastrophic results, not least for the Spanish mines. Caracalla (188-217) restored the aureus to its former place, and as a result the Spanish mines, which had been in crisis, reactivated their production. However, the resuscitation of the mines seem to have been short-lived, and the lack of later material in the archaeological record shows that gold production effectively came to an end in the opening decades of the 3rd century.

The work carried out by the Romans was spectacular. It is estimated that forty million cubic meters of earth were removed from the central zone alone. What now remains is a small part of what, according to experts in the field, were the original Medulla Mountains. A mountain of 200 billion cubic meters totally disappeared. Researchers and experts estimate that they achieved 3 grams of gold per ton on average, although others cite three grams per cubic meter. It is estimated that over one million kilos of gold were taken from these mountains during the two hundred years that the Romans were there (over €50 billion in todays money). Ten per cent of the Roman Empire’s annual income came from here.