Litter-Buggery

Tuesday, December 29, 2020

Spain has an enviable system of describing distances. Rather than kilometres, they use time. Or they may use rest-stops, cigarettes smoked, the number of songs from Joan Manuel Serrat listened to (and sung along with) on the CD player, or even brothels (depending on your route, Murcia to Almería can be a six-brothel voyage). For shorter peregrinations, I use dustbins.

I walk the dog each day past four green 'contenadores'. These large bins, together with smaller empty waste-baskets with an inverted bin-liner bobbing merrily out of them, are liberally distributed along my route, as indeed they are all over Spain. There is a tendency of course on the part of the public to eschew the friendly nearby dustbin and just hurl the empty gin-bottle out into the campo, but we try. We try.

People often like to leave their rubbish near the giant receptacles, perhaps to stop it from feeling lonely. The excuse might be that maybe the lid is broken, or that they fondly imagine someone might need an unwanted sock to pair with the one they have already, or perhaps an almost new toilet lid. Sometimes, they even put their trash inside the bins (where, in the snootier neighbourhoods, the beggars will then climb in afterwards and throw everything out again).

Unlike some northern nations, Spain has never held a poor opinion towards rubbish, and it is traditionally thrown on the floor, or out of windows or the open doors. I wonder sometimes if that was why they invented windows - an easy place to discard unwanted trash.

I remember my first shrimp, at the age of thirteen. I dutifully dismembered it, chooped its head and left the reamins on the bar. No, no, pantomimed the barman, flapping his hands, the garbage goes on the floor! And he was right. Under my very feet, a woman was mopping the marble flags and loading the detritus into a bucket. They used to say that one could tell a good tapa-bar by the amount of crap on the floor.

Sometimes, as we are lighting a cigarette or searching for the next brothel in the car (with its garish lights and brutish architecture), we must swerve violently as a surprise missile is hurled out of the window from the vehicle in front. It's usually a wrapper of some sort, or maybe a bottle (can, plastic or glass). Evidently, not wanted on voyage.

When walking the dog, along the side of the road we will find glass, trash, rubbish, human poop (it's a terrible thing to be caught short in the campo), dead things, empty wine bottles (do drivers savour the last drop of the vino before jettisoning the bottle?), plastic sheets and bags, mungy bits of clothing and sundry french letter packets. Then, depending on the neighbourhood, clumps of discarded copies of the free English-language press, some pages of which may have found a final use...

Indeed, as I now live in an area noted for its plastic farms, I see where the old rolls of mangled plastic are left in untidy pìles alongside the road, or where bits whip against a piece of barbed wire in the wind, or maybe make their way slowly and majestically towards the sea (often in the back of a truck). In some cases, the plastic sheets are simply ploughed back into the land. Goodness knows what the dog will find on his walk...

For some reason, there is no Spanish version of 'Keep Britain Tidy', even though those contenadores are emptied daily (rather than twice a month as, apparently, the humble dustbin is in the UK). A Spanish friend explained to me once that the bins here need to be emptied regularly 'as we eat fresh food rather than things out of tins' (which seems to be an argument that's hard to refute).

With the exception of rampant litter-buggery, I love Spain.

5

Like

Published at 1:16 PM Comments (4)

5

Like

Published at 1:16 PM Comments (4)

Adra (because it's there)

Thursday, December 24, 2020

Over the years, I have visited many parts of Spain. I've studied in Seville, lived in Madrid, spent long hospital time with my late wife in Pamplona and, during the nineties, run offices in various pueblos on the costas, which necessitated regular visits (and a lot of aspirins). There was also an office in Mojácar, the town that I have called 'home' for most of my life. I know the province of Almería pretty well, with the last few years spent living just outside the capital, and, of course, I've made endless trips to various towns and villages over the past fifty years.

But, until now, I had never been to Adra.

This hardly makes me unique. No one has ever been to Adra.

Adra, at 25,000 inhabitants, is the large fishing port that signals the end of Almería when heading along the Mediterranean west into Granada and Málaga. In the old days, it was a turn-off from another switch-back curve on the ghastly road between Almería and Málaga (there were 1,060 of those horrible switch-backs, as the old N340 curved and wiggled through the sharp hills above the coast-line), but now the fishing town of Adra is close to the bright new motorway. There is still little inclination to visit the place, which, as I finally discovered this weekend, is a shame.

According to Wiki (we couldn't find a tourist office), Adra is the fourth oldest town in Spain, founded in 1520BC. Let see... it was originally called Abdera by the Carthaginians, was flattened by an earthquake in 881, yadda yadda, it had the first steam engine in Spain and is a big fishing port...

Yep, the man from the Wiki clearly hasn't visited the place either. Confusingly, Google gives more space to another Adra, which is an agency of the Seventh-day Adventist Church (and may help to explain why no one ever visits).

Anyhow; in the spirit of 'because it's there'. I went with my pareja to give the car a good growl, see the sights, buy a 'He who is tired of Adra is tired of Life' bumper sticker, and hopefully enjoy a good fishy lunch. The road to Adra, designed apparently by more of the school of those who only know the town through its motto: 'En Adra, perro que no muerde, ladra' (the dog that doesn't bite you, barks at you instead), swings you in through and out in a confusing swirl, but then, as your heart sinks and you wonder whether the next town down, Motril, might be open for business, the planners relent and bring you back down to the harbour.

That day, there was by chance a flea market. We walked around, admiring a stand selling Franco memorabilia, and eventually, while looking for a bullfight poster for a friend, we bought a couple of naïf pictures from another dealer. They look great in our kitchen. That day, there was by chance a flea market. We walked around, admiring a stand selling Franco memorabilia, and eventually, while looking for a bullfight poster for a friend, we bought a couple of naïf pictures from another dealer. They look great in our kitchen.

Adra appears to be a place that is worth getting to know, or maybe a great place to hide, as nobody would ever think of looking for you there. It's probably chock-full of museums and interesting relics and buildings, plus a few wanted counterfeiters and smugglers (the murderers prefer Marbella, obviously), but we were there principally for a cold beer and a warm fish-head.

Alicia didn't want to eat in the Club Náutico (you can never go wrong in a Club Náutico in my opinion) so we walked past some dowdy looking places, including a joint that described itself from outside as 'American/Italian', before alighting on the Taberna La Granja, a splendid and atmospheric bar/restaurant in a back street. We ate a satisfyingly expensive lunch there, served by the owner himself (intrigfued, no doubt, in meeting the first visitors to the town in decades) and returned, replete, to the car.

La Granja - and you are on your own here - has a great Tarta de Whisky. The owner pours half a bottle of scotch over it to make sure that it meets with the diner's approval.

Worked for me, although I may have got a speeding ticket while we were driving home...

1

Like

Published at 7:37 AM Comments (2)

1

Like

Published at 7:37 AM Comments (2)

Share With Your Dog

Monday, December 14, 2020

I am one of those people who rarely gets sick - much beyond a cold, a cough and the traditional annual week in bed with 'man flu' just after Christmas to catch up on my reading.

The dog is ill though - he has leishmaniasis. This nasty disease is a parasitic infection that comes from the no-see-ums that fly around in clouds over stagnant water (there's an obliging pool in our nearby dry river bed). These midges bite on the ankles in humans, without causing much more damage than a passing itch, but they appear to be mortal for most dogs in my barrio (not all, my last hound managed to bark at the neighbours for twenty two years before death took her). The dog is ill though - he has leishmaniasis. This nasty disease is a parasitic infection that comes from the no-see-ums that fly around in clouds over stagnant water (there's an obliging pool in our nearby dry river bed). These midges bite on the ankles in humans, without causing much more damage than a passing itch, but they appear to be mortal for most dogs in my barrio (not all, my last hound managed to bark at the neighbours for twenty two years before death took her).

My dog has the disease, and a vet recently discovered a medicine that keeps the infection in check - it's a pill that humans take against gout called Alopurinol. He's managed over a year now on one of these pills crushed daily into his doggybix and seems to be doing well on the diet.

Gout is a nasty little complaint. It's like a tiny piece of gravel behind the bone in one of your extremities. I looked it up on the Internet after my toe turned red, started to hurt and swelled up. Too much brandy apparently. I was limping around shouting blue buggery, taking a whack at any child or animal that came to close to me and wondering whether to go and see the doctor. But then, I thought, what about the dog's daily dose!

So, here we are. The dog and me are sharing the same box of tablets. One for you my dear and one for me.

Ahh, that's better.

1

Like

Published at 8:42 PM Comments (1)

1

Like

Published at 8:42 PM Comments (1)

Spain's Frontier Towns - Near no Modern Borders

Wednesday, December 9, 2020

|

| Vejer de la Frontera |

What do Jérez, Arcos, Morón, Vejer, Chiclana and a number of other Andalusian towns have in common? Their full and proper names are ‘...de la frontera’. They are all ‘on the frontier’, and yet, since nothing is simple in Spain, they aren’t. The Cádiz city of Jerez de la Frontera, for example, is 242 kilometres away from the nearest frontier – that’s to say, Portugal.

One could argue that early Spanish cartographers were not very good at their jobs, or that the Royals were never wrong, but the fact is, the place names make perfect sense when you roll back a few centuries to the time of the Moors and the Kingdom of Granada.

The Christian forces of Aragon and Castile were slowly (oh, so slowly) taking the country back from the Moors. These North African colonists had been in control of almost all of Spain for anything up to seven hundred and fifty years (depending on which bit we happen to be talking about) although, by the beginning of the fifteenth century, the writing, whether in Arabic or in Latin, was definitely on the wall. Granada, as we know, capital of the ‘Nazarí Kingdom’, fell in 1492, the same year as Spain discovered the Americas.

This would be known as Spain’s greatest time.

Stood between the Christian and Moorish territories while leading up to the final push in the later XV Century were a number of frontier towns which watched uneasily over a no-man’s-land (or ‘Terra Nullius’ as it was officially known – an unclaimed space between the two forces). During its existence, this border strip had great military, political, economic, religious and cultural importance. Beyond being a border like many others, it was for more than two centuries the European border between Christianity and Islam. It was, therefore, a place of exchange and barter, which kept alive in both territories the spirit of the Christian crusade and the Islamic jihad together with the chivalric ideal, already anachronistic in other European territories.

It also made possible illicit economic activities, such as trade in oriental products, as well as regular military incursions, aimed at taking booty, as well as the captivity of hostages with whom to maintain the slave business, or simply to negotiate the redemption of captives. Religious orders took sides in this regard. The border was a key element in the formation of the identity of Andalucía and in the formation of the vision of Islam throughout Spain.

While another culture might have dropped the Arab names once conquered, the Spanish have appeared gracious enough to keep them. Such towns as Vélez-this and Alhama-that are quite common (the first comes from the Arab word for ‘land’, the second for ‘baths’). Indeed, anything beginning in Al – comes from the Arab prefix ‘the’: Alhambra, Almería, Alpujarra...

Al-Ándalus, as far as the Moors were concerned, means and meant anything which was under Moorish control in the Peninsular – at some point, almost as far north as Pamplona.

Of all of the ‘frontera’ towns, mostly located in Cádiz, the largest in Jerez de la Frontera, with its magnificent Alcazar, an XI Century Moorish fortress. The Moors called the city ‘Sherish’ and held it until 1264, although the Christian forces controlled the surrounding lands from 1248. The town would become a ‘frontier’ with the Granada kingdom.

Jerez is the largest non-capital city in all of Andalucía, with a population of around 210,000 souls (larger than Cadiz – its provincial capital – as well as Almería, Jaén and Huelva). It is known for wine, horses, flamenco and motorcycles.

Morón de la Frontera, in the province of Seville, owes its appellative to having a major garrison, once it had been conquered in 1240 by Fernando III, from which the Christian forces could harass the Moors.

Morón de la Frontera may not have a frontier, but the nearby American-controlled air-base of Morón (actually located in the next-door municipality of Arahal) – which has been going since 1953, of course does. You’ll need a passport to make it past the heavily-armed gate and on to the PX store...

Another town on our list is Chiclana de la Frontera. It is just up the road from both Conil de la Frontera and Vejer de la Frontera. There must have been a gleam in the eye of King Fernándo IV when he got into the swing of naming his towns in the Most Loyal Province of Cádiz...

Chiclana is just 24 kms south of the city of Cádiz and has become a tourist resort with the largest number of hotel beds anywhere within the province. With a population of over 84,000, the town is only marginally smaller than its nearby capital city. The town is noted for its monuments and its wineries.

Next door’s Conil de la Frontera, again in reference to the far-off ‘frontier’ with Granada, is a beautiful resort which grows five-fold during the summer season.

The ‘frontier’ town with the most charm must nevertheless go to Vejer de la Frontera, a small coastal town with a view of the Atlantic. Vejer is a member of the ‘Prettiest Towns in Spain Association’ and is a maze of narrow streets and white houses.

I like the story of how a Moorish prince and his Christian damsel were forced to leave Vejer as the enemy forces arrived. She tearful, he defiant. ‘I’ll build you another town as pretty as this one’, he promised her and, back in North Africa, that’s what he did, building in her name the beautiful turquoise-blue town of Chauen.

Moving beyond the frontiers of Andalucía (well, barely), mention should be made of Murcia’s frontier town. Puerto Lumbreras, the Port of Lights (roughly), may have been a trading or military port, but it is around 32 kilometres from the coast and thus its name refers to its frontier status, as it is separated from Almería’s Arab-sounding Huercal Overa on the other side of the wide no-man’s-land strip, in this case some 23 kilometes, and was a heavily-garrisoned fortress-town.

For two hundred years, the sometimes uneasy border between the Christian and Moorish cultures stood until Spain’s famous ‘Catholic Kings’, Fernándo of Aragon and Isabela of Castille, brought the ‘re-conquest’ to an end in 1492, and Spain was born from the ashes.

2

Like

Published at 7:33 PM Comments (1)

2

Like

Published at 7:33 PM Comments (1)

I briefly ran a bar in the hills and made some very nasty tapas. Urrrpf.

Tuesday, December 1, 2020

My first (and penultimate) foray into business was to open a bar in the Almería mountain village of Bédar in 1976, when I was a just a young lad.

The Bar was called 'El Aguila': The Eagle (because of the view). I sold a local brew called Aguila beer and Aguila cigarettes (clever, eh?).

The beers, served in small bottles of 20cc (known as quintos or - if you can pronounce it - cervecillas) came from a warehouse in the nearby gypsy-town of Cuevas, and I could fit seven crates of them in my car. Thirty to a crate. The smokes, a brand similar to Ducados (strong black tobacco) came from a shop in Bédar called 'la tienda de Simón', which sold everything - from a wheelbarrow to a shower-bucket. A tin of butter to a postage stamp. Cigarettes and a tot of brandy. A useful place indeed.

Creating a bar takes a bit of work.

I had three old houses in Bédar, bought by my father for ten thousand pesetas (sixty euros) off of Old Gregorio in 1966. My father, whose Spanish at the time was non-existent, wasn't sure if he'd just paid for a very expensive lunch at Pedro's bar or if he was now the owner of three houses bought - apparently - off someone Pedro refered to as Hermano. Herman to his friends.

I fixed them up, slightly. Knocked a hole through the walls. Built a kitchen somewhere, brought in a few mattresses and a sofa. The three houses, now one, had electric but no mains water. Nor did the rest of the village, of course.

I put in a wrought-iron window terrace in the larger room for the bar, placed a plank of wood on top and, with a couple of bottles of banana brandy found at Simón's, was about good to go.The cross-eyed water man - who brought supplies in four large clay cántaros on his donkey - kept everything sluiced down, and the lavatory on the terrace was strictly soak-away.

The doctor from Los Gallardos came for an official look. He said the downstairs was fine, but the upstairs was off-limits. Three rooms and a terrace for the public to enjoy: a bit of razzmatazz for the Bédar denizens.

The bar in theory was to be run with EJ Whyte, an Irish American who lived in Bédar and was responsible for bringing fellow-American artist Fritz Mooney to the area on the back of a BSA in around 1962. However, after enormous trouble getting work permits (think on this Brexiteers) - many trips to Almería, papers, fruitless visits, long walks up and down looking for obscure offices and people who had 'gone out for a coffee', stamps and photographs... EJ finally told the little man in the employment office in Almería to shove it up his backside, leaving me, as it were, in sole control.

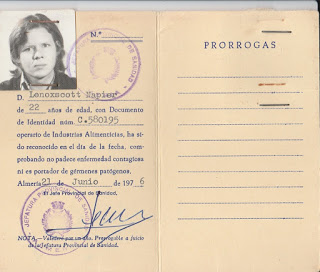

The card in the photo is the official permit to handle food. They give you a nail-brush and peel your eyelids.

Thus, I ran the bar by myself (sometimes my friend and local builder Juanico joined me - once arriving with a live and evidently stolen sheep which, after meeting a violent end on the bar-room floor, improved the tapas for a week or so). Beers and tapas. A quinto beer and a really quite horrible tapa cost 10 pesetas (seven céntimos in today's money). Since the local youth liked to play chinos (spoof) for a round, I found that I was drinking rather a lot. Perhaps many bar-owners do. I remember one in Los Boliches who used to surreptitiously finish all the dregs from the returned glasses. I rather doubt he's still going today.

My tapas weren't very good. I had bought a chapa, a large piece of iron plate, off Juan el Fraguero from Mojácar, and this was put on a small gas-fire. I would cut frankfurters sideways, sliced down the middle, with a squirt of hot sauce. I also offered costellitas: the bit of bone on the end of a rib with a nub of gristle hanging off it, also with a squirt of hot sauce. Bédar has long since had trouble with ulcers, apparently - it was good hot sauce. Then there was the mysterious bits of off-cuts in the bag of costillitas from the butcher's daughter in Cuevas. Juanico identified them as being rams' testicles. Apparently she must have liked me, he reckoned.

I had a record player and four of five records - the most popular being Nat King Cole singing in Spanish. Nat's accent was worse than my father's, but the clientele seemed indulgent.

My neighbours weren't convinced I wasn't running a brothel. One day, old dad came in for a chatico de vino (six pesetas). After about a dozen of these, he was sure that the place was of a moral rectitude seldom found in Spain. Several of the local kids actually carried him, gripping his arms and legs as he sang one of Nat's most popular numbers, home to his missus.

The bar was fun - sometimes. But it wasn't a money-maker. At threepence a beer, I wasn't making a fortune. My girlfriend didn't like it much, once hitting me on the head with a beer-crate.

Realising I was not cut out for the hospitality business, I rented the place out after a few months to some Brit football enthusiast called Roger for a 'Greenie' - our name for a 1,000 peseta bill (6€) - per month. He was popular with the local lads and no doubt improved their soccer skills. Of course he never paid the rent (he probably lost it on chinos), although the tapas improved slightly...

The rest of the house, about two thirds of it if you counted the creaky bits upstairs, carried on as mine. The ceilings were made of beams, cane and plaster. Some of the beams were made of pine and others were just pita, the century plant stalk. I can tell you, they aren't very firm after a few decades...

One day, EJ came down from Madrid to stay the night. I left him the key to the house and drove to Mojácar. EJ relates that he suddenly woke with a terrible thirst, remembered there was a bar next door, and battered down the intervening wall using a butano-bottle as a sledge-hammer. He says he served himself a cool beer from the bar and meekly went back to sleep again. House guests, hey?

A few years later, I fixed up the whole building properly into one large and slightly eccentric house.

It's sold now.

4

Like

Published at 6:50 PM Comments (7)

4

Like

Published at 6:50 PM Comments (7)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|