The Empty Villages of Spain

Monday, November 23, 2020

The authorities are worried, as more and more people move to the cities and away from their moribund villages in the quinto pino (the sticks). Small villages are losing their inhabitants and even drying up completely, ending as news items along the lines of ‘Entire Spanish village for sale’ in the newspapers.

Depriving them of services certainly doesn’t help – no bank, no pharmacy, no school, no town cop and even – Yarggh – no bar.

There have been some protests recently, as the villagers march on Madrid (waving their pitchforks). But the politicians, keenly aware of the small (and evidently decreasing) number of votes in play, are not all that interested. The campaign ‘Teruel Existe’ notwithstanding (Teruel is a small and bitterly cold province, merrily ignored and avoided by all and sundry), the province has lost fifty per cent of its population in the past 100 years.

Interestingly, and to prove a point, Teruel Existe turned itself into a political party last year and, to the rueful surprise of all the other political groups, it won a seat in the Spanish parliament.

|

|

Alcontar (Almería) lost almost 10% of its population in 2018.

|

But, and despite some teleworkers moving to the campo and a healthier lifestyle, the bloodletting continues. In Almería, over sixty of the 102 municipalities claim a population loss: municipalities where the young have moved to The City to find jobs, romance and a decent tapa. Those old houses in the pueblos are kept, as often as not, by the now-displaced owners who visit once a year (in their fancy cars) and they may still appear on the local padrón (to vote for their cousin Paco, of course). In short, the real numbers are even worse than the statisticians admit.

So, what to do?

Property is cheap enough in them thar hills, and as long as the ecologists in the regional government don’t mind about foreigners moving in, providing jobs, money and a hankering for tinned beans in the local shop, there is a small gain to be made for the pueblo. A campaign perhaps? After all, the kids aren’t coming back, so we will need new (or rather, old) settlers to replace them. Imagine that, a Spanish promotion aimed at foreigners, but not at tourists!

Other potential and useful settlers might be those poor refugees, washed up on Spanish soil. Go and till that land!

Sometimes, one of those peaceful villages could make an excellent old people’s home: a community benevolently run by the social services, with proper treatment for those who could benefit from country life under supervision.

The Government could step in, of course, and say – no town under two thousand without a bank, a chemist, a bus-service and a school!

And maybe, as some villages hopelessly die, amalgamate them into nearby municipalities. We don’t need on paper 102 communities in Almería if ninety would be enough.

1

Like

Published at 11:30 AM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 11:30 AM Comments (0)

I Might As Well Get It Out Of My System

Wednesday, November 18, 2020

I was once asked to make a list of ‘things I didn’t like about Spain’. It would be easy enough to make one about the things I do like, and it would run to many pages, but the things I don’t? Hum. Well, there the bureaucracy which drives us all, Spaniards and foreigners alike, up the wall. Las cosas de palacio, van despacio, say the Spanish sententiously, as if by giving the creaking bureaucratic system an excuse, wrapped up in a popular saying, it all makes sense. In the past two years, for example, no one has managed to get Spanish nationality because the twenty-five thousand people whose job it is to sort out the paperwork have instead taken a disturbingly long lunch-break.

People sometimes have to live rather poorly – a house with no water or electric for example – for a number of years because of some elusive bit of paper trapped in the bottom of a drawer belonging to a public official who has been off work with a runny nose for thirty-six months, but absolutely should be back any day now.

I try and live with the system, since I love it here. My Spanish wife knows nothing of HP Sauce and shepherd’s pie, and she has never had a Yorkshire pudding or even a mushy pea. I am nevertheless proud of her as she sips her afternoon cup of English tea with milk and one sugar (my only remaining British weakness).

But, we were talking about Spanish wrongs – like corruption. How they get away with it defeats me. The country is positively leaping with crooked bankers, politicians and manufacturers of ladies hosiery. They stash millions in off-shore financial paradises, pay no tax, and – most remarkable of all – are highly esteemed by large swathes of the population. OK, in my personal experience, I’ve had more trouble from thieving Brits that crooked Spaniards (lawyers maybe – there’s always hungry lawyers here), but over the years, I’ve found that owning nothing helps keep them away, along with plenty of garlic.

So, the list. We’ve done bureaucracy and corruption, there’s also littering.

How can a proud nation like the Spanish merrily toss as much garbage into the countryside as is humanly possible? The beaches, the roadside, the streets and the public buildings are caked in debris. Everywhere is thick with plastic, flattened beer cans, bottles, graffiti, cardboard and rubble. I take my trash home with me, or at the very least, leave it on the back seat of the car for a few years, but our friends and neighbours? They scatter it everywhere across this great country with gleeful abandon.

Noise, I suppose. This country is deafening. Happily, with the passage of the years, I have become quite deaf, so am immune to the cacophony of the world’s second loudest population (after the Japanese whose houses, for Heaven’s sake, have paper walls).

Lastly (and believe me, I’ve been thinking about this list for years), I would say, parking. There’s never enough, as though the designers feel they can squeeze more money out of shops and buildings if there are as few parking spots as possible. Then the few spaces that are there will as likely as not have a caravan of dustbins clogging them up.

As if there was a serious litter problem here!

So, many people (at least in my local village) will park two abreast – en paralelo – with their warning lights on. ‘I’m sorry, I really am, but I just needed to stop the car for a moment as I zip into the bank, buy a lottery ticket and have a very quick coffee with my lawyer’. You can always get past. Yesterday, I had to drive at least fifty metres along the pavement, because the road was completely blocked by two double-parked cars. Luckily for us all, they both had their warning lights on.

But what are a few minor niggles, when compared to the endless wonders of this great country we have chosen to call home?

1

Like

Published at 10:17 AM Comments (4)

1

Like

Published at 10:17 AM Comments (4)

On the Road to La Matanza

Thursday, November 12, 2020

It was one of those adventures that sometimes spring up over a beer. It seemed that old Antonio el Perejil (Tony the Parsley) had recently gone to his reward and had left his house to his son, who wanted to sell it.

The house was, apparently, quite close to Níjar, recently brought into the pack of Almería's Most Beautiful Towns (actually, there should be about fifty on the list), and up a track.

Into the Nowheres. Into the Nowheres.

We drove into Níjar only to find that the road which, as Google said, led to a walkers' path, was closed. Reversing down a narrow street and around the other way, we waved down an old fellow and asked him which was the best way to get to La Matanza.

A great name, no? It's called La Matanza because this was the final stand of the Moors in the Níjar of the Reconquista, around 1490. 'Oh', says the old man, 'you mean Antonio el Perejil's place? He's dead you know'.

Yes, we knew that.

'Well, you go out of town, along that road, then up this other one, round there (he waved vaguely) and it's just a hop and a skip. I was there only a few years back, lemme see, well in around 1980 now that I think of it'...

I helped the old boy back onto the pavement and we pulled a u-turn and, as they say here, we abandoned Níjar.

The new road we found turned into a street and from there into a track, and then a river bed and then a track again. We were about ten kilometres along this route, by now with alarming drops on one side and cliffs on the other. Google had fizzled out completely and we were wondering whether to go on or turn back when a van abruptly arrived in a gentle cloud of dust (you are never completely alone in Spain). Now my Spanish is pretty good and Alicia is from Almería, but we had trouble with the man who climbed out of the Renault to have a look at us. 'Gor and blast', he said 'La Matanza? It's just down vere'.

|

| The house is the higher one, on the right. It comes with forty hectares of land. |

We peered uneasily over the drop. 'Of course she'll make it', said the man, looking appreciatively at our car, 'mine does it, no worries'.

We arrived at the house, which had some olive trees behind it and a courtyard to the right. One of the neighbouring houses (they were all empty) had solar panels and a full reservoir.

In the Bad Old Days, during and after the Civil War, a place like La Matanza, an isolated clutch of a dozen houses, was probably a good place to be. It was safe, ignored and produced its own food and water. There wasn't much to do after night fell, especially if you had run out of candles, but one rises early in places like this.

Now, there's no one left - apart from the man with the van - although he would be living back in Níjar, where there's electricity, TV and a number of decent pubs.

A tired sign pointed back towards the town, at just 4.5kms. That was probably the Google walkers route.

It was a cold and blustery day, so the pictures aren't as bright as they would normally be, up in La Matanza, which looked, we decided, like a modest version of Machu Picchu, but without the tour buses.

|

| Sea views? Of course there are sea views! |

It's for sale, if you're interested I'll mention you to Antonio's son. It's probably ideal for someone who wants to get away from it all and can't afford Algeria.

4

Like

Published at 6:40 PM Comments (0)

4

Like

Published at 6:40 PM Comments (0)

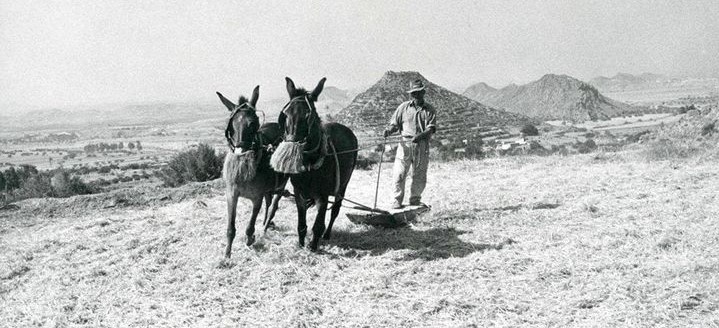

The Lost Art of Hay Surfing

Wednesday, November 11, 2020

Every farm in southern Spain has something called an 'era' which is a flat dirt circle, I think called a threshing circle in English, where the hay would be put after being cut with a scythe. A wooden board with rows of knife-like wheels underneath was pulled by a donkey and driven with long-reins by the farmer. Weight must be applied to the board in order to cut the hay, hence the children. There are actually several different boards with different types of knifed wheels for each phase of cutting. It was a very exciting time for the children when the farmer called them to come and sit on the board while he went round and round. It takes several days to cut the hay into small pieces and release the grain from the stalk. It is a sticky job, in the heat you get covered in pieces of hay and it is a bit like a ride at an amusement park, bumping up and down it is a rough ride especially when the hay is in the centre at the beginning, it gets to be a smoother ride as the hay gets spread around the circle. The board sometimes even flips over. Every farm in southern Spain has something called an 'era' which is a flat dirt circle, I think called a threshing circle in English, where the hay would be put after being cut with a scythe. A wooden board with rows of knife-like wheels underneath was pulled by a donkey and driven with long-reins by the farmer. Weight must be applied to the board in order to cut the hay, hence the children. There are actually several different boards with different types of knifed wheels for each phase of cutting. It was a very exciting time for the children when the farmer called them to come and sit on the board while he went round and round. It takes several days to cut the hay into small pieces and release the grain from the stalk. It is a sticky job, in the heat you get covered in pieces of hay and it is a bit like a ride at an amusement park, bumping up and down it is a rough ride especially when the hay is in the centre at the beginning, it gets to be a smoother ride as the hay gets spread around the circle. The board sometimes even flips over.

No harm is done because you just fall into a huge pile of hay. You must watch your fingers though and can’t hold on to the board for risk if being cut by one of the blades. When the threshing is done you must wait for a windy day and with a naturally grown pitch-fork, you throw the hay in the air. These pitch-forks grow on a tree in the shape of a fork and after being whittled down a little make the perfect pitch-fork. On the windy day, and after hours of repeating this procedure of throwing the hay in the air, the cut hay is on one side of the era and the grain on the other, it is quite ingenious really, each to be stored and used throughout the year. I would like to have shown you a picture of the pitch-forks but ours was lost. We have an era on our property and across the street is another era that is shared by three houses: it is communal property and doesn’t belong to any one of the houses but to all three. It is things like this that make buying land in Spain difficult. For example a long time ago your grandfather may have traded a donkey for the large algarrobo tree on the corner of his property, the donkey is long since dead but the tree on your land now belongs to someone else.

From Barbara Napier's Animo Stories here. The two photos come from the same 'era' in the hills above Mojácar. The first one dates from the 'fifties, the second one features our daughter and was taken in the early 'eighties.

0

Like

Published at 11:11 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 11:11 PM Comments (0)

Fake News and How to Control It

Tuesday, November 10, 2020

Fake News. Bad, right? The Government thinks so and is introducing rules to stop the media from posting fake or manipulated items by setting up a permanent commission against la disinformación - (as they prefer to call it). The commission, says El Español here, is purely PSOE-controlled and without the presence of Podemos (a regular victim of bulos).

These journalistic inventions, as we know, are often used to create anger, disdain or hopelessness in the readers or viewers - for political or economic gain. They are not to be confused with slanted reportage, or even propaganda (using selective facts for manipulative purposes), which happens the whole time, depending on the politics of the media in question. We are talking here about purposely-produced lies.

The current debate is of course whether this is a righteous struggle against these items of hoax news, or simply government censorship (with all the sinister connotations which that supposes).

Some news-services currently use 'fake news' without any particular limit - OKDiario is one of at least a dozen notorious examples. Their recent editorial on the subject at hand says ‘Now it will be Little Franco Sánchez who decides which news is true and which is fake’.

Many more bulos are found in the Social Media (although both Facebook and Twitter have recently taken to some form of ‘fact-checking’ claims published on their platforms).

A local English-language free-sheet famously fired off a hoax news-story last August based on fake interviews with Government ministers. Indeed, it made the pages of Spain’s leading fact-checker here. The point being that fabricated stories like this can cause unnecessary alarm amongst the public.

Fake news is a recognised problem in Brussels, but the EU's strategy against disinformation is ‘aimed towards Russia and China, not as a surveillance of the national media’ (here). Indeed, the official opinion from the European Commission on Spain’s, ah, putative control of fake news is “Any initiative in the field of disinformation must always respect legal certainty and freedom of the press and expression. But we have no reason to think that this has not happened in the case of Spain”.

Maldito Bulo here (the Spanish version of Snopes) is more or less on board with this ‘ambiguous rule’ (yet of the opinion that independent sources – like Maldito Bulo and others – should be the ones to monitor the news and social media), but the press is not at all happy. The AMI (the national association of newspapers) is quoted here as saying 'You can't take away our freedom of expression').

The leader of Vox doesn't like it either: 'The Tyrant Sánchez introduces Censorship', writes Santiago Abascal in a characteristic tweet. Slightly more alarmingly, the Spanish Secret service CNI is also against introducing institutional controls against fake news (for professional reasons, we wonder?).

In short, it is one thing to monitor fake news, but it’s quite another thing to seek to stop it. Maybe the threat of fines coupled with disclosure might help cool the jets of the wily fabulists.

0

Like

Published at 8:51 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 8:51 PM Comments (0)

A Trim Little Number in Yellow

Friday, November 6, 2020

(Spain: somewhere on a narrow and dusty road to nowhere). I was driving along just this side of safe, with one eye on the speedo and the other on the rear-view mirror. Half asleep and all bored. Then, the mobile phone rang. One of the kids had been messing with the damn thing so I wasn’t immediately aware what was going on. The CD was belting out some fine blues and there was a thin weepy sound running below, just on this side of conscious. A mild arrhythmia over my heart finally helped me put it together – the damn phone in my shirt was vibrating and… yes… actually crying to be answered. (Spain: somewhere on a narrow and dusty road to nowhere). I was driving along just this side of safe, with one eye on the speedo and the other on the rear-view mirror. Half asleep and all bored. Then, the mobile phone rang. One of the kids had been messing with the damn thing so I wasn’t immediately aware what was going on. The CD was belting out some fine blues and there was a thin weepy sound running below, just on this side of conscious. A mild arrhythmia over my heart finally helped me put it together – the damn phone in my shirt was vibrating and… yes… actually crying to be answered.

Which was a relief in one sense: I’m not going to keel over the steering wheel with a cracked pump and disappear with the old banger over the cliff. At least, not this time.

Talking on a mobile phone in Spain is illegal when you’re driving. Like many other agreeable activities that one can get up to behind the wheel, yes… many agreeable activities…

Whoa! I almost left the road there. And there’s one helluva drop on the right, down to a distant valley full of olive trees. Jeez – that was close.

So, since I don’t have a chauffeur like the head of the traffic department, an ambitious fellow called Pere Navarro, and therefore can’t answer the phone and plan my next piece of business; and, unlike Mr Navarro, who is concerned about the heady mixture of saving lives, pissing people off and furthering his brilliant career in the ruling PSOE, all I’m after is a bit of peace and quiet, getting on with life and following the Spanish dream of being left alone. In fact, I just want to sell another set of encyclopedias without any interference from nobody to some family that probably doesn’t want them, can’t read and write properly and… Oh Hell! I'd better pull off the road.

Last thing I need is to lose some more points off my licence. They already took three last month for driving in carpet slippers instead of the approved brogues. Drivers don’t get corns and blisters in that cute fantasy life dreamt up by the city-living fat-cat pink champagne swilling pencil-chewing jerks that get to invent all these new intrusive laws while helping themselves to another brown envelope and, in passing, running our country into the ground.

There’s a handy lip on our roads, called the ‘arcén’. That’s where you go when you need to stop the car and do something else besides driving. Like kick one of those hidden speed-cameras to death. You don’t want to spend too long on the traffic-curb as it can be quite dangerous, with truck drivers thundering past your narrow ledge of safety or perhaps, if they are nodding off as their tachometer clicks into the red, they might drive straight in, through and over you.

Thumpity thump. The sod never even noticed. Probably thought it was a new kind of ‘sleeping policeman’.

Then, there are the Guardia Civil road-cops; ‘los primos’, we call them. The cousins.

You can’t loiter with your vehicle on the arcén unless you have your emergency lights on, are wearing a kind of high visibility yellow fluorescent jacket, available at a store near you, and have placed your warning triangles both fifty metres before and indeed after to warn other drivers of your untoward immobility.

Good old Pere enjoys his lunch somewhere, thinking of all the good he’s done.

If they show up, the sheriff of Nottingham’s men are going to want to see if you carry a spare pair of glasses, an inspection sticker, a shoe-press, anything at all on the back seat (apart from mother), a nice clean driving licence and the rest of it – and of course, while they are there, they will be looking for illegal immigrants hiding under the spare wheel, traces of narcotics in the ashtray and an illegal radar trap apparatus stuffed down your jumper. Don’t worry about your insurance papers; they’ll have checked you already on their dashboard computer.

Here we have the ‘points system’, just like they do in other countries. How many times do second-rate politicians produce that trick to help one swallow the medicine – ‘Oh, and in Finland you have to carry an extra pair of snow-shoes, so it’s not just here’…?

We start with twelve gold stars on our licences and the police are under strict instruction to start the carving. Aggressively. That and collect money like a Carney at a fun-fair. They take any more off me and, Hell, I’m walking home. It’s all right for the traffic tsar; he can always get another chauffeur.

All this to answer the phone, which has stopped ringing by now anyway. Still, when you work for yourself, pay a fortune in gas and social security, you don’t want to miss a phone call – it might be a sale.

So, I hide the half-empty flask of whiskey under the seat, next to the crowbar; pull the stupid yellow day-glo number on, up over my head. Look like a booby. The price tag is flapping on my chest so I wrench it off and (no one looking) throw the bloody thing off the edge of the road.

To the boot of the car to get the triangles. You need to carry two of them – one for ahead and the other for behind. They had better not blow over; the cops might think I just threw them onto the road in a fit of bad temper.

I take the first one up the road and pace out fifty metres, forty-nine, fifty. Then back to the car and repeat the same process the other way. I will have walked over a quarter of a kilometre by the time I'm through with this but, anyway, I’ve dumped the second warning sign on the ground here on the curve and I've brought the phone and am now gonna…

‘Eh, Oiga’!

There’s some bloke up-road from me. The hell he came from? He’s standing a hundred metres away, just by my front triangle. It trembles in the slight wind. ‘You wanna buy this thing off me?’ he shouts.

‘What’s up?’

‘This triangle, you wanna buy…? He repeats.

‘You can sod off, you bastard!’

A huge trailer rumbles past and the triangle, grateful for the distraction, is blown off the border and flitters down into the valley below.

I’ve picked at the phone now for the re-dial and am walking back to the car, one eye on the chancer and the other out for the cops. I’ve got my surviving triangle tucked protectively under my arm where it gently tears a hole in my fluorescent pajama top.

It was a wrong number. But you already knew that.

1

Like

Published at 2:56 PM Comments (1)

1

Like

Published at 2:56 PM Comments (1)

Going Cheap: One Castle!

Tuesday, November 3, 2020

Almería's Alcazaba was once placed on the market by the City Hall. It must have been a bit strapped for cash when, in 1866, the castle and its 37 hectares of extension were put up for sale at the bargain price of 1,175 pesetas (seven euros), which even then, sounds a bit cheap. Almería's Alcazaba was once placed on the market by the City Hall. It must have been a bit strapped for cash when, in 1866, the castle and its 37 hectares of extension were put up for sale at the bargain price of 1,175 pesetas (seven euros), which even then, sounds a bit cheap.

The city wanted to expand in the direction of the castle and so the offer included the proviso that anyone who bought it would have to demolish the hulk that crowned the hill behind Almería and haul away all the rubble. Tourism hadn't been invented yet and only a few nutters were enchanted by the historic or scenic value of the monument, described by Wiki as an XI Century fortified complex.

(The Alhambra in Granada was also ready for demolition more than once).

The demolition clause proved the undoing of the sale, due to its prohibitive cost. Nevertheless, much of the old castle walls were successfully demolished in the late XIX Century.

The Alcazaba finally received protection as Monumento Histórico Artístico in June 1931.

When the coronavirus is over, pencil it in for your next visit. The Alcazaba (al-qasabah - what a great Moorish word - it means a 'walled fortification in a city'!) and then take a turn around Almería's tapa bars.

0

Like

Published at 6:58 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 6:58 PM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|