You see the famous rock near Antequera from every direction. From the flat plains it juts up, suddenly and harshly. Known to the Spanish as la Peña de los Enamorados (the lovers' rock) and to many as the Indian's Head (or Charles de Gaulle rock) it is visible for miles, a way-marker for those travelling north-south between Córdoba and Málaga, or east-west between Granada and Sevilla.

You see the famous rock near Antequera from every direction. From the flat plains it juts up, suddenly and harshly. Known to the Spanish as la Peña de los Enamorados (the lovers' rock) and to many as the Indian's Head (or Charles de Gaulle rock) it is visible for miles, a way-marker for those travelling north-south between Córdoba and Málaga, or east-west between Granada and Sevilla.

Legend has it that two lovers jumped from the rock when their warring families refused to acknowledge their love. Early versions of the tale say it was a young man from Antequera and a young woman from Archidona. Other versions say it was an Arab prince and a servant girl, or a Muslim princess and a Christian slave boy. Whichever you believe, the story is clear (and sadly unchanging) - families unable to accept difference, chase their children to a tragic death.

This visit to Antequera arose from a very 21st century mistrust of scams, combined with an equally 21st century use of the internet. A phone call out of the blue asking me to take my car to a garage for a free software upgrade had rung alarm bells. Having received several of the "Hello I'm calling from Microsoft and you need to pay me lots of money to fix your computer"-type phone calls, I was a little suspicious. I shouldn't have been. A quick internet search demonstrated that SEAT cars in other countries were being recalled for a software update linked to a minor problem with the airbags. The internet even showed me a photo of the man who had called, in his SEAT uniform! So, fears allayed, I took the car to the Antequera workshop, passing as always la Peña de los Enamorados. And of course all went well and it was simply good customer service.

Free time in Antequera and at last a chance to visit the Dólmenes - megalithic tombs, temples, or ritual sites. A statue known as El Caminante (The Traveller) gazes implacably across the plains from near the Dolmens visitors' centre towards the lovers' rock. Created in 2005 by the artist Miguel García, he somehow manages to link the people of 6,500 years ago who lived out their lives on these plains, with modern humankind, living such extraordinarily different lives from those of our ancestors.

Free time in Antequera and at last a chance to visit the Dólmenes - megalithic tombs, temples, or ritual sites. A statue known as El Caminante (The Traveller) gazes implacably across the plains from near the Dolmens visitors' centre towards the lovers' rock. Created in 2005 by the artist Miguel García, he somehow manages to link the people of 6,500 years ago who lived out their lives on these plains, with modern humankind, living such extraordinarily different lives from those of our ancestors.

Walking between the two main tombs in the July heat you couldn't help but wonder why such labour was expended. The structures use enormous stones, in the same way that Stonehenge does (built probably 2,000 years later). It is believed that this is evidence of co-operation amongst many different local farming communities, working towards a shared goal, putting aside tribal differences to achieve something of value to all. I can't think of a modern equivalent - it seems that with greater knowledge has come an increased tribalism and a reduced ability to share or to live or work together. Perhaps these thoughts were running through my head this week in particular because of watching the devastation wreaked in Palestine and Israel. Certainly the stories of the Lovers' Rock and of humankind's unwillingness to hold hands across racial or religious divides, seem as timeless and unchanging as the rock itself.

Walking between the two main tombs in the July heat you couldn't help but wonder why such labour was expended. The structures use enormous stones, in the same way that Stonehenge does (built probably 2,000 years later). It is believed that this is evidence of co-operation amongst many different local farming communities, working towards a shared goal, putting aside tribal differences to achieve something of value to all. I can't think of a modern equivalent - it seems that with greater knowledge has come an increased tribalism and a reduced ability to share or to live or work together. Perhaps these thoughts were running through my head this week in particular because of watching the devastation wreaked in Palestine and Israel. Certainly the stories of the Lovers' Rock and of humankind's unwillingness to hold hands across racial or religious divides, seem as timeless and unchanging as the rock itself.

Inside the dolmens the wonder and the wondering continued. Burial sites, centres to come together to worship and to pray for good harvests .... the full explanation escaped me. Possible stories swirled through my mind as I struggled to imagine their lives, 6,500 years ago. Children, adults, farming, learning, eating together, playing together, and all the time gazing at the Lovers' Rock, just as hundreds of thousands of modern people do every day, if they remember to look up from their iPads and Androids.

Inside the dolmens the wonder and the wondering continued. Burial sites, centres to come together to worship and to pray for good harvests .... the full explanation escaped me. Possible stories swirled through my mind as I struggled to imagine their lives, 6,500 years ago. Children, adults, farming, learning, eating together, playing together, and all the time gazing at the Lovers' Rock, just as hundreds of thousands of modern people do every day, if they remember to look up from their iPads and Androids.

Modern technology got me here - the internet allayed my suspicions, and the sat-nav led me to the SEAT workshop on an industrial estate and then to the dolmens. Progress, of course. I am happy to take advantage of the technological advances available to me. And it would be ridiculous to say that the "simpler" life of those farmers 6,500 years ago was anything to be hankered after. But somehow walking here and thinking of how much has changed in these six or seven millennia, makes me acutely aware of the new technologies and their capacity for both good and evil. Of course communities, races, tribes, have always fought. They fought each other for survival, for shelter, for food. But wars nowadays are not for those basics, most of the time (except for the besieged in occupied territories). Wars now are for land, for oil, for dominance, and for the imposition of one set of beliefs over another. The technology we have at our disposal is used to kill at great distances, and the mass media is used to spread misinformation, and to create distrust of difference. Call me naive, but if this is progress, could it not be used better?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

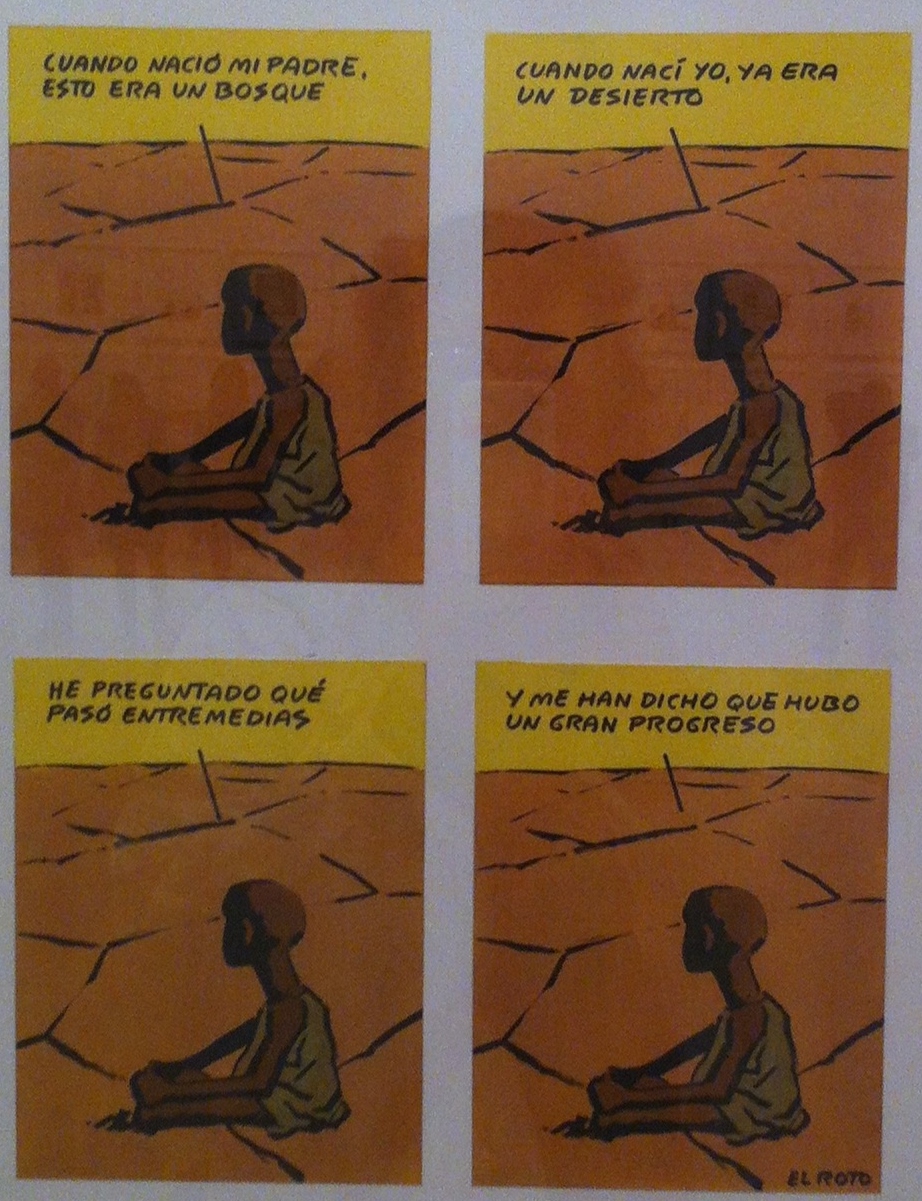

I make no apology for using this picture a second time. It’s by the cartoonist of “El País”, Andrés Rábago, who draws under the pseudonym “El Roto” (the broken).

The child is saying “When my father was born, all this was woodland. When I was born, already it was a desert. I asked what had happened in between. And they told me there had been great progress.”

© Tamara Essex 2014 www.twocampos.com

THIS WEEK'S LANGUAGE POINT:

Saying things are pointless, not worth it etc.

No sirve de nada / De nada sirve – It’s no use, it’s no good.

No sirve de nada preocuparse en ello – It’s no use worrying about it.

De nada sirve persuadirme – It’s no good trying to persuade me.

No tiene sentido tener un coche si nunca lo usas – It’s makes no sense to have a car if you never use it.

Vivo solo un paseo de aquí y por tanto no merece la pena coger un taxi – I only live a short way from here so it’s not worth getting a taxi.

No merecía la pena ir a la cama / irse a la cama / irnos a la cama – It wasn’t worth going to bed.