187 - Empty Benches in Empty Squares - Lockdown Day Nine

Thursday, March 26, 2020

LOCKDOWN DAY TWO:

Monday is the first “normal” day of the lockdown. I go to the surgery for routine blood tests. Everyone is maintaining social distance. Doctors and nurses are wearing masks and gloves. The village is VERY quiet. I use the opportunity to go to a couple of food shops. In the first, they have put tape on the floor to keep people queuing at a good metre’s distance from each other, and that works well. It feels a bit like a board game, when the person at the till leaves the shop we can all move one square forward. In the bakery, a sign prohibits more than one customer at a time, and there is a tray to put the money on.

We learn to ration our “treats” – in the morning the socially-distant doorstep chat (shout) with the neighbours. In the afternoon a walk to the shop. A chance to talk to humans, whether the can of tuna you buy is absolutely essential or not.

A purple button has appeared on our health app. This app, Salud Responde, allows us to book GP or nurse appointments (usually the same day or the next). The purple button, marked “Coronavirus” is slightly too vibrant, and throbs ominously. I haven’t dared press it as it has the air of being poised to squirt disinfectant in my face. A purple button has appeared on our health app. This app, Salud Responde, allows us to book GP or nurse appointments (usually the same day or the next). The purple button, marked “Coronavirus” is slightly too vibrant, and throbs ominously. I haven’t dared press it as it has the air of being poised to squirt disinfectant in my face.

In the squares all the benches are empty.

It looks and feels very strange.

LOCKDOWN DAY FOUR:

Every night at 8pm, across Spain people take to their balconies and join together to applaud the health workers and the emergency services. It is incredibly moving. Videos from the big cities show neighbours leaning over, waving at each other, and clapping. It is sparser in my village, but as I clap on my top terrace our thin and scattered applause merges above us and floats off to join in the nation’s gratitude.

The Spanish king addresses the nation, as does the Prime Minister. The general view is that this will go on for a couple of months beyond the initial fortnight.

LOCKDOWN DAY SIX:

The shop at the top of my road) has upped its game. We queue outside until someone leaves. A squirt of disinfectant on the hands as you enter. It is no surprise that here nobody is taking advantage of the situation – I bought a 12-pack of loo rolls for 1,40€.

There’s bad news from a dear friend whose brother has the virus. He’s in hospital in Madrid so she can’t go to see him, and he’s in his 80s. It brings it home. It’s not just about funny memes and clapping on balconies.

On the patio it is very quiet. There is almost no traffic, and the road improvements in the village have had to stop. The sound of birdsong is everywhere. It was there before, but we had forgotten to hear it.

LOCKDOWN DAY EIGHT:

Life inside the prison cell has just got a whole lot better. A bunch of women friends have done battle with technology and we manage a group video call between five of us. I have an extra-long shouty-chat with Ana-Mari opposite, she on her balcony, me inside my front door but with the glass section open, shouting through the bars.

From next door Isabel waves, but today she doesn’t come out. She’s at the kitchen table with her sewing machine, making face-masks for the healthcare staff and for local people, she is one of a team of volunteers across the village doing this, and a bigger team across Andalucía. Not all heroes wear capes.

We discover that the Spanish Prime Minister is going to ask parliament for an extension to the lockdown, to April 12th. We knew it was coming, but there is still a sinking feeling.

It’s drizzling, which cuts down slightly on terrace-exercise. On LBC radio this morning they interviewed a Frenchman who has just completed an actual Lockdown Marathon since their confinement began in France. His terrace is 7-metres long, and he has counted up all those 7-metre chunks and has done 6,028 lengths of his terrace. In many ways it’s a metaphor for seeing the bigger picture, seeing how small contributions, small steps, add up and contribute to something big and valuable.

Like staying indoors, for the greater good. #MeQuedoEnCasa

© Tamara Essex 2020 http://www.twocampos.com

7

Like

Published at 11:41 AM Comments (3)

7

Like

Published at 11:41 AM Comments (3)

186 - Lockdown in the Pueblo - Day One

Sunday, March 15, 2020

It’s just as well that the Spanish prime minister is easy on the eye. Guapo, we say in Spanish. Just as well, as we sit glued to the television watching his almost daily pronouncements. It’s just like those days last year when we couldn’t tear ourselves away from BBC Parliament.

And he is very definitely on a Spanish timetable. The Friday afternoon governmental declaration was due at 2.30. President Sánchez finally emerged at 3.15. The more significant Saturday evening official announcement of the state of emergency was due at 8pm. The Twitter feed of La Moncloa (the equivalent of No 10 Downing Street) was full of sarcastic comments, and questions as to whether the president was on Canary Isles time (an hour later than mainland Spain). In the end, he was an hour and a half late, as the cabinet meeting had gone on for over seven hours.

He spoke clearly, with both compassion and authority. He emphasised that we are all in this together – but here it actually rang true, unlike when that phrase was used by the UK Tory government about austerity. Later on Saturday night it rang even truer, as it emerged on social media that Sánchez’ wife has tested positive for Covid-19. So we really ARE in it together right up to the president’s family, and he emphasised the need to act together and sensibly in order to protect the entire nation. He spoke clearly, with both compassion and authority. He emphasised that we are all in this together – but here it actually rang true, unlike when that phrase was used by the UK Tory government about austerity. Later on Saturday night it rang even truer, as it emerged on social media that Sánchez’ wife has tested positive for Covid-19. So we really ARE in it together right up to the president’s family, and he emphasised the need to act together and sensibly in order to protect the entire nation.

And he raised his papers, shook them in the air, and told us that the lockdown would start with immediate effect, 10pm on Saturday night. By chance, just as he finished, right across Spain people broke out into applause on their balconies. It wasn’t for him, it was a social-media spread idea to show thanks to all our health and emergency workers. It was a huge success, and the videos were incredibly moving – a visible and audible show of gratitude, and I sincerely hope that it was heard by those to whom it was aimed. And he raised his papers, shook them in the air, and told us that the lockdown would start with immediate effect, 10pm on Saturday night. By chance, just as he finished, right across Spain people broke out into applause on their balconies. It wasn’t for him, it was a social-media spread idea to show thanks to all our health and emergency workers. It was a huge success, and the videos were incredibly moving – a visible and audible show of gratitude, and I sincerely hope that it was heard by those to whom it was aimed.

Today, Day One of the Lockdown, it is Sunday so it would be a quiet day anyway. We are allowed out to buy food and go to the bank. These little pleasures, along  with taking out the rubbish and the recycling, will no doubt become the highlights of our day. “Social distancing” is the new buzz-phrase. Here in the village the shops (yesterday, before the lockdown) were well-stocked and nobody was panic-buying. This morning I shall go for a VERY short walk to see if one of the mini-supermarkets is open. As much to get some fresh air and stretch my legs as anything else. Sunday is usually a sofa-day. I’m beginning to wonder what a sofa-fortnight will be like. with taking out the rubbish and the recycling, will no doubt become the highlights of our day. “Social distancing” is the new buzz-phrase. Here in the village the shops (yesterday, before the lockdown) were well-stocked and nobody was panic-buying. This morning I shall go for a VERY short walk to see if one of the mini-supermarkets is open. As much to get some fresh air and stretch my legs as anything else. Sunday is usually a sofa-day. I’m beginning to wonder what a sofa-fortnight will be like.

This morning we had a “socially-distant” gathering of the women in my little callejón (cul-de-sac). One in pyjamas, one in a bathrobe, the rest in trackies or floppies. One up on her balcony, the rest of us on our doorsteps. Five of us, 45 minutes together but apart, though Antonia beckoned me closer while she  disappeared indoors to gather up 14 beautiful freshly-laid eggs for me. “They just keep on laying!” she said exasperatedly, carefully passing me the bag of treasure. We finished our gathering with an agreement to do it every morning. Not breaking the lockdown, not really bending the rules, but managing to be a little bit social while maintaining social distance. All in all, it’s not the worst place to be trapped. disappeared indoors to gather up 14 beautiful freshly-laid eggs for me. “They just keep on laying!” she said exasperatedly, carefully passing me the bag of treasure. We finished our gathering with an agreement to do it every morning. Not breaking the lockdown, not really bending the rules, but managing to be a little bit social while maintaining social distance. All in all, it’s not the worst place to be trapped.

Social media is both a blessing and a curse. An absolute pandemic of mis-information! Yet a few gems, small groups springing up offering local help, ensuring that neighbours have all they need. And jokes. Of course there are  jokes. A debate is raging on social media about why hairdressers are allowed to remain open, while other retail and service shops are not. The reason is for older and disabled customers who can’t wash their hair, but it has become a major talking-point (internet displacement activity, maybe?). So of course, the idea emerged that bars could rebrand as hairdressers! (la peluquería)! jokes. A debate is raging on social media about why hairdressers are allowed to remain open, while other retail and service shops are not. The reason is for older and disabled customers who can’t wash their hair, but it has become a major talking-point (internet displacement activity, maybe?). So of course, the idea emerged that bars could rebrand as hairdressers! (la peluquería)!

I have no idea whether the approach adopted in Spain is the right one, or the one in the UK. None of us do. I don’t doubt the medical experts on whom the UK is relying, but nor do I doubt the Spanish ones. All of them are aiming to keep us all healthy, and they have come to different conclusions as to how to do that. We won’t know which is right. Not until it is way too late.

© Tamara Essex 2020 http://www.twocampos.com

7

Like

Published at 4:38 PM Comments (3)

7

Like

Published at 4:38 PM Comments (3)

185 - The Best-Laid Plans .....

Sunday, March 15, 2020

I get to the bar first, bang on time. You can take the woman out of England but you can’t take English punctuality out of the woman. Miguel makes my coffee and disappears into the miniscule kitchen to tip some brown sugar into a tiny espresso cup for me. I roll my eyes at him and he says he’s decided to order some sachets of brown at last. ¡Por fin! I’ve teased him often enough about it.

His bar is above a swimming pool accessories shop, it’s near the crossroads up towards Periana, and it’s easy to park. Adriana has collected Lola and Charo in Málaga and they are on their way to pick me up. They park, Spanish-timetable, late, as expected, but I just can’t assume that will happen so I’m always first to arrive. The noise levels increase as my three friends clatter up the wooden stairs and order their coffees, very specific, very demanding, very un-English. We’re not kissing or hugging, unusually, and the first of a hundred conversation topics is THAT virus.

After coffee the Spaniards want to visit the nearby English supermarket, and for the umpteenth time I explain that the name “Arkwright’s” comes from a TV comedy series, and the origin of ‘wright” as a maker, an artisan, such as a  wheelwright. Lola loves studying English and has a thousand questions. Adriana has not a word of English but makes a beeline for Gale’s lemon curd, ignoring my plaintive reminder that it is nothing like as nice as the farmshop lemon curd they bought last year on a visit to my Dorset pueblo, Shaftesbury. Then the biscuit aisle for Scottish shortbread, then the array of Twinings teas. Finally we grab bread for our picnic, and carry our goodies out to the car. wheelwright. Lola loves studying English and has a thousand questions. Adriana has not a word of English but makes a beeline for Gale’s lemon curd, ignoring my plaintive reminder that it is nothing like as nice as the farmshop lemon curd they bought last year on a visit to my Dorset pueblo, Shaftesbury. Then the biscuit aisle for Scottish shortbread, then the array of Twinings teas. Finally we grab bread for our picnic, and carry our goodies out to the car.

Up the hill and then off onto the track up to Adriana’s campo house. First along the parallel track to open the stopcock so we will have water. Not only for our  next coffees, but more importantly so we can water some of her trees. It’s why we go up there, officially. That’s the pretext, but it’s mostly just for the companionable picnic and conversation. Stopcock opened, she padlocks the box and jumps back in the car. We turn and the track snakes higher up to the junction where her chain blocks the access. next coffees, but more importantly so we can water some of her trees. It’s why we go up there, officially. That’s the pretext, but it’s mostly just for the companionable picnic and conversation. Stopcock opened, she padlocks the box and jumps back in the car. We turn and the track snakes higher up to the junction where her chain blocks the access.

The pretty drawstring bag is removed from the glove compartment and the bunch of tagged keys is produced. Lola, Charo and I carry on chatting while Adriana fiddles with the padlock. One topic is put to bed and another starts up, until suddenly we realise that she is still fighting the lock and the chain remains firmly in place. Lola leaps out to help, to equally pointlessly try every key in the obdurate padlock. Puzzled, Adriana peers into the drawstring pouch, and we tip out all the odd keys that can accumulate as if drawn to each other and reproducing in the bag. There is nothing the right size. Never mind, it’s only a short walk up the remainder of the track, and we sort out our bags containing our contributions to the shared lunch before stepping over the chain and climbing the slope.

Arriving on the terrace with its spectacular view of the lake and the mountains, we fall to our usual tasks, bringing chairs and the table round to the side with the view, while Adriana went to open up the house. Lola regales us with a story and  we are laughing as we unstack plastic chairs. Suddenly we see Adriana’s face as she frantically works through the bunch of keys. None of them works in the front door. The lock remains as uncompliant as the padlock had. You can almost hear our brains working it out … we have mountains of food and drink but no knives, bottle-openers or plates. We have plenty to eat but no access to the bathroom or the kitchen. We settle around the table to think, spreading out bread, cheese and olives on the paper they were wrapped in. Adriana phones her son; he was up here last weekend, but he says there was no problem with the keys then. we are laughing as we unstack plastic chairs. Suddenly we see Adriana’s face as she frantically works through the bunch of keys. None of them works in the front door. The lock remains as uncompliant as the padlock had. You can almost hear our brains working it out … we have mountains of food and drink but no knives, bottle-openers or plates. We have plenty to eat but no access to the bathroom or the kitchen. We settle around the table to think, spreading out bread, cheese and olives on the paper they were wrapped in. Adriana phones her son; he was up here last weekend, but he says there was no problem with the keys then.

It’s early March and the sun beats down. The cold meat I’ve brought, a speciality  of my pueblo, needs a knife. Charo’s stuffed peppers are not finger-food. We can’t make the planned salad. But we fail to make an alternative plan, as the conversation meanders over new ground, and the last bit of cheese gets finished off. Finally one of us, I don’t remember who, suggests that we take ourselves off to a venta, a rural bar-restaurante. The food gets bundled back into the bags, the chairs and the table are returned to their places, and we make our way back down to the car, stepping over the unyielding chain. of my pueblo, needs a knife. Charo’s stuffed peppers are not finger-food. We can’t make the planned salad. But we fail to make an alternative plan, as the conversation meanders over new ground, and the last bit of cheese gets finished off. Finally one of us, I don’t remember who, suggests that we take ourselves off to a venta, a rural bar-restaurante. The food gets bundled back into the bags, the chairs and the table are returned to their places, and we make our way back down to the car, stepping over the unyielding chain.

We contour round the mountain track and head off in a different direction. Adriana takes us through Periana and along to los Baños de Vilo. This is the  Axarquía, the inland area east of Málaga. Not as well-known as the hotspots west of the city, not so popular with incomers. Our secret. These are the mountains I see from Colmenar. These are the hills, draped with fruit trees and wandered over by goats, that are my stamping-ground. As always, the Spanish women are puzzled as to how their guiri-friend, the foreigner in their group, has explored these out-of-the-way tracks, when they haven’t. Axarquía, the inland area east of Málaga. Not as well-known as the hotspots west of the city, not so popular with incomers. Our secret. These are the mountains I see from Colmenar. These are the hills, draped with fruit trees and wandered over by goats, that are my stamping-ground. As always, the Spanish women are puzzled as to how their guiri-friend, the foreigner in their group, has explored these out-of-the-way tracks, when they haven’t.

We cut through to los Baños de Vilo, a Moorish tower and pool with natural sulphurous water. In the hot sun the smell of the sulphur was rank and we were not tempted in to bathe. Back in the car, the cheese and olives now a distant memory, our driver and guide took us on to the hamlet of Guaro. I’ve often parked there for the varied hiking trails, the route up to the dramatic Zafarraya Pass, and the renowned restaurant which is where we now head. A shared banquet of scrambled eggs with young garlic shoots, soup made of local freshly-picked asparagus, and a salad the size of the mountain across the valley. We cut through to los Baños de Vilo, a Moorish tower and pool with natural sulphurous water. In the hot sun the smell of the sulphur was rank and we were not tempted in to bathe. Back in the car, the cheese and olives now a distant memory, our driver and guide took us on to the hamlet of Guaro. I’ve often parked there for the varied hiking trails, the route up to the dramatic Zafarraya Pass, and the renowned restaurant which is where we now head. A shared banquet of scrambled eggs with young garlic shoots, soup made of local freshly-picked asparagus, and a salad the size of the mountain across the valley.

Then a hike, a stop to eat the tasty strawberries Charo had brought, and back to  the car (there may also have been the theft of a fat lemon, warm to the touch, for each of us). Down towards civilisation just as it gets dark. The whole day has gone, and the full moon rises behind the palm fronds. Miguel’s bar is closed now but we cross to the other one for a final coffee before jokingly bumping elbows instead of a goodbye kiss. the car (there may also have been the theft of a fat lemon, warm to the touch, for each of us). Down towards civilisation just as it gets dark. The whole day has gone, and the full moon rises behind the palm fronds. Miguel’s bar is closed now but we cross to the other one for a final coffee before jokingly bumping elbows instead of a goodbye kiss.

It wasn’t the day we’d planned, it wasn’t the long afternoon relaxing in the kitchen and on the terrace of the campo house. “The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft agley” as Robert Burns wrote. It couldn’t have mattered less.

© Tamara Essex 2020 http://www.twocampos.com

4

Like

Published at 12:30 PM Comments (0)

4

Like

Published at 12:30 PM Comments (0)

184 - Nothing has Changed ....?

Sunday, February 23, 2020

At Málaga airport they let me through the normal passport queue. A relief. The EU citizens’ queue. My first flight after THAT date. Exit day. The guy at the passport desk said we could continue to use that line all this year, apart from odd days where they would “trial” sending us through the other queue, just to check that it’ll all work smoothly. Landing at Bournemouth nothing had changed, but then it is only a portakabin-style arrivals hall, nothing very high-security. At Málaga airport they let me through the normal passport queue. A relief. The EU citizens’ queue. My first flight after THAT date. Exit day. The guy at the passport desk said we could continue to use that line all this year, apart from odd days where they would “trial” sending us through the other queue, just to check that it’ll all work smoothly. Landing at Bournemouth nothing had changed, but then it is only a portakabin-style arrivals hall, nothing very high-security.

In the press they insist that nothing has changed. Some so-called journalists even state dogmatically that we haven’t actually left yet. They are clearly wrong. But so are the ones who say that nothing has changed yet, and that everything stays the same until December 31st. They are wrong too.

I’m on my flight back home, after a week visiting friends in Dorset (and stocking up on teabags and hot cross buns). Over the next few days I must confirm numbers in the bar where we have organised a surprise farewell party for a good friend being forced back to live in the UK. There is always a tangle of reasons, but she would not be going if the British government had not decided that being tough on freedom of movement was their top priority. I must pop in at Los Ángeles Malagueños de la Noche to pick up their message of thanks to her. She has been tireless in organising a network of volunteer collectors and drivers, the doll workshops for the children’s presents and the spongebag assembly lines, and all this on top of rescuing countless abandoned cats. Undoubtedly, back in England, this whirlwind of selfless energy will waste no time in making herself invaluable to her local human and feline communities, but none of that takes away from the fact that she cannot live where she has made her home. That’s a change.

You know that fundamental principle, “No taxation without representation”? Well that has changed, too. Those who have lived overseas for more than fifteen years had already lost their votes in the UK. But at least they have been able to vote in the municipal elections in their adopted country. Not any more. Those of us in Spain, yes. Spain has signed a treaty extending suffrage to us, despite us being “extra-comunitario” (outside the EU). Not so in all EU countries. Social media groups of British people in Europe are full of complaints that many people are paying taxes both in the UK and in their adopted country, yet have no vote anywhere. That’s a change.

And we check those advice groups every day. Those valiant groups of brilliant volunteers who pore over every missive from the UK and Spanish governments, updating us on every change. THEY know that it’s not true to say that nothing  has changed. We await news about how Spain will organise the issuing of the new cards. The TIE. Tarjeta de Identificación Extranjera. The foreigners’ card. For extra-comunitarios. For outsiders. Our little green residency cards, applied for with such trepidation, received with disproportionate delight, will be taken from us this year. We might be done alphabetically, we don’t know how they will administrate it. For Spain it’s a big task. For each of us, it’s another change. A piece of plastic that identifies us as extra-comunitarios, as outsiders. As people with “permission to reside” but not the RIGHT to live in our homes. That’s a change. has changed. We await news about how Spain will organise the issuing of the new cards. The TIE. Tarjeta de Identificación Extranjera. The foreigners’ card. For extra-comunitarios. For outsiders. Our little green residency cards, applied for with such trepidation, received with disproportionate delight, will be taken from us this year. We might be done alphabetically, we don’t know how they will administrate it. For Spain it’s a big task. For each of us, it’s another change. A piece of plastic that identifies us as extra-comunitarios, as outsiders. As people with “permission to reside” but not the RIGHT to live in our homes. That’s a change.

And now the UK has published its new points-based immigration system and has classified all the EU care-workers and hospitality staff as “low-skilled”. The Facebook groups of EU citizens in the UK have exploded with anger. Thousands more are abandoning their applications for Settled Status and heading home. They understand perfectly well that the new system is for future incomers, but they have felt the change in atmosphere, they have felt unwanted, and this has been the last straw. That’s a change.

So we say to the journalists, the political commentators, the phone-in hosts, and the politicians: we are no longer “Remoaners” but we are still British citizens. And every time you insist that nothing has changed it is another reminder that we were never remembered in all this, never considered.

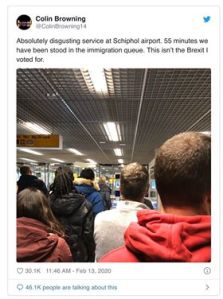

In the media last week there was much laughter at the now infamous Colin, the Brexiteer who was stuck in a queue at passport control at Schiphol Airport, going through the slow, non-EU queue. He tweeted his disgust, adding the hashtag  “Not the Brexit I voted for”. Well yes, Colin, yes it is. Did you imagine that stopping freedom of movement would not impact you? Or me? Or my friend moving back? Sigh. But, with effort, I remember my mantra – blame the conners, not the conned. I genuinely hope that all the good things that people believed they were voting for DO appear. I hope that working conditions improve and that people who felt that the eastern European workers were depressing their wages and their prospects, now get their promotions and their pay-rises. I hope for a fully-funded NHS. I hope the government will replace all the EU funding that Wales, Cornwall and Cumbria have lost. I hope that taking back control means that Parliament and the justice system are in control (though the new Attorney General seems to take a different view). I hope our farmers will be reimbursed for the lost subsidies, and that food standards and animal welfare will be improved. I spend a lot of time hoping. “Not the Brexit I voted for”. Well yes, Colin, yes it is. Did you imagine that stopping freedom of movement would not impact you? Or me? Or my friend moving back? Sigh. But, with effort, I remember my mantra – blame the conners, not the conned. I genuinely hope that all the good things that people believed they were voting for DO appear. I hope that working conditions improve and that people who felt that the eastern European workers were depressing their wages and their prospects, now get their promotions and their pay-rises. I hope for a fully-funded NHS. I hope the government will replace all the EU funding that Wales, Cornwall and Cumbria have lost. I hope that taking back control means that Parliament and the justice system are in control (though the new Attorney General seems to take a different view). I hope our farmers will be reimbursed for the lost subsidies, and that food standards and animal welfare will be improved. I spend a lot of time hoping.

Everyone wants this to work. Everyone. Regardless of how we voted. Food security, jobs, the environment and working conditions – they are all way too important for us not to all be on the same side. We’re all leavers now. I want it to work, truly. But don’t palm me off with platitudes that nothing has changed. For those in the UK that might be true. But from where we stand over here, a lot has changed, and not for the better. I hope that Colin does get the Brexit he voted for, and that all the 17.4 million get the one they wanted, too. Because if not, what the hell has it all been for?

The airport bus whizzes me in to the centre of Málaga. There’s a fiesta going on,  a festival of graffiti in Plaza de la Marina, combined with a basketball festival. Málaga doesn’t change much. Even when it changes, it doesn’t really change. There’s pretty much always a fiesta of some sort in Málaga. a festival of graffiti in Plaza de la Marina, combined with a basketball festival. Málaga doesn’t change much. Even when it changes, it doesn’t really change. There’s pretty much always a fiesta of some sort in Málaga.  I wander as the artists demonstrate urban art and the youngsters shoot hoops, and finally I settle with a coffee in the 23°C sunshine. Please don’t change, Málaga. Over the last four years I’ve discovered that I don’t like change, much. I wander as the artists demonstrate urban art and the youngsters shoot hoops, and finally I settle with a coffee in the 23°C sunshine. Please don’t change, Málaga. Over the last four years I’ve discovered that I don’t like change, much.

© Tamara Essex 2020 http://www.twocampos.com

2

Like

Published at 11:32 AM Comments (10)

2

Like

Published at 11:32 AM Comments (10)

183 - A Toothbrush for Christmas

Friday, February 14, 2020

They were already queuing to get back into the hostel for their lunch when I parked outside on Christmas Eve, risking leaving the car in the “Personas Autorizadas”  spaces. The line snaked right to the corner, and you could see in their posture a sort of resignation, an aspect of helplessness. All of them standing, mostly motionless, just waiting, with nothing else to do and nowhere else to be, until the hostel staff open the door to let in the waiting people. spaces. The line snaked right to the corner, and you could see in their posture a sort of resignation, an aspect of helplessness. All of them standing, mostly motionless, just waiting, with nothing else to do and nowhere else to be, until the hostel staff open the door to let in the waiting people.

But it’s not locked. As I headed towards the door the people at the head of the queue stepped aside and a man with a scruffy beard and dead eyes opened the door to let me through. I thanked him and he looked at me blankly, expecting nothing from me, no thanks, no interaction.

Two uniformed police officers stood in the hostel foyer, relaxed, largely ignoring both the long queue outside, and the much shorter queue inside at the unstaffed reception desk. Nobody was talking. The waiting residents inside automatically made way as I queue-jumped them to peer through the reinforced glass of the reception desk.

Nobody there, so I headed for the door to the left of Reception that leads through to the offices. One of the police officers jumped across to open it for me,  simultaneously preventing a resident from following me. In her office I found the social worker that I’d been to the Consulate with for passports a couple of years ago, and told her I’d brought a carful of sponge bags, enough for all the 120 temporary residents of the Málaga city homelessness hostel. She grabbed another worker and they followed me out to unload. Just then the reception worker came back, and immediately left the queue unattended again and came to help unload. simultaneously preventing a resident from following me. In her office I found the social worker that I’d been to the Consulate with for passports a couple of years ago, and told her I’d brought a carful of sponge bags, enough for all the 120 temporary residents of the Málaga city homelessness hostel. She grabbed another worker and they followed me out to unload. Just then the reception worker came back, and immediately left the queue unattended again and came to help unload.

Only the social worker remembered me from two years ago. The other staff were new (there is a massive turnover of staff here, it’s not a popular posting for funcionarios (the Spanish version of the civil service). Yet the residents, the police,  and the staff, had all made way for me and allowed me through the security door that separates the “front-of-house” from the staff offices without questioning me. We dumped the last sack of sponge bags indoors, they thanked me, the two policía local opened the door for me and told a resident to get out of my way (I shot him an apologetic glance but he wasn’t meeting my eyes), and I returned to my illegally-parked car. and the staff, had all made way for me and allowed me through the security door that separates the “front-of-house” from the staff offices without questioning me. We dumped the last sack of sponge bags indoors, they thanked me, the two policía local opened the door for me and told a resident to get out of my way (I shot him an apologetic glance but he wasn’t meeting my eyes), and I returned to my illegally-parked car.

Looking back at the still waiting queue, silent, immobile, heads bowed, resigned, I could see the difference, the reason why I could walk past the queue unchallenged, why I could expect courtesy from the police, why I could walk with no compunction straight through a security door. It’s because my head was up and my shoulders  back. Because, although my clothes were as crumpled as those of the residents, I wore them with an air of confidence, of entitlement. Because although not an authorised person, I had parked in the space for “Personas Autorizadas”, confident that I could smile and blag my way out of any problem. It’s in the way you walk, and it’s in your eyes. Everybody recognises it, and it sets you apart from the people in that queue. Entitlement. Privilege. back. Because, although my clothes were as crumpled as those of the residents, I wore them with an air of confidence, of entitlement. Because although not an authorised person, I had parked in the space for “Personas Autorizadas”, confident that I could smile and blag my way out of any problem. It’s in the way you walk, and it’s in your eyes. Everybody recognises it, and it sets you apart from the people in that queue. Entitlement. Privilege.

We don’t do presents so much now, my friends and I. Just little gifts, something nice to unwrap. It’s the thought that counts. But there in the hostel, on Christmas Eve  when the sponge bags were given out, the simple gift of a toothbrush, some shower-gel, a couple of small soaps and a razor, was intended to be both useful and thoughtful. It is about the most minimal present you can imagine. But pretty good if your walk no longer has that swagger and your head is no longer held so high, and when what you need most is a toothbrush for Christmas. when the sponge bags were given out, the simple gift of a toothbrush, some shower-gel, a couple of small soaps and a razor, was intended to be both useful and thoughtful. It is about the most minimal present you can imagine. But pretty good if your walk no longer has that swagger and your head is no longer held so high, and when what you need most is a toothbrush for Christmas.

© Tamara Essex 2020 http://www.twocampos.com

3

Like

Published at 11:54 AM Comments (1)

3

Like

Published at 11:54 AM Comments (1)

181 - Anybody Got Any Knickers?

Thursday, September 26, 2019

Church halls pretty much anywhere in the western world all look remarkably similar. This one was just like the one in Yorkshire I went to in the 1960s as a  Brownie, and the one in south London in the 1990s when I hosted fundraising jumble sales, and then in Somerset in the 2010s when I ran charity training courses. This one, though, was in a small Axarquía town in inland Málaga province. Brownie, and the one in south London in the 1990s when I hosted fundraising jumble sales, and then in Somerset in the 2010s when I ran charity training courses. This one, though, was in a small Axarquía town in inland Málaga province.

Ranged along the standard-issue folding tables were heaps of naked and half-dressed Barbie dolls, piles of teeny dresses, hats and trousers, and bags of colour- separated miniature boots and shoes. And five magnificent women, Alison, Janet, Barbara, Mary and Trish. They work on this project throughout the year, knitting, sewing, crocheting, shampooing dolls’ hair, putting together matching outfits. Then each doll goes (temporarily, they assured me) into a plastic bag with four outfits and a little checklist. Finally, in December, they will be carefully placed into a pretty cloth bag and delivered to Los Ángeles Malagueños de la Noche ready for Kings’ Day on January 6th when the children get their presents. separated miniature boots and shoes. And five magnificent women, Alison, Janet, Barbara, Mary and Trish. They work on this project throughout the year, knitting, sewing, crocheting, shampooing dolls’ hair, putting together matching outfits. Then each doll goes (temporarily, they assured me) into a plastic bag with four outfits and a little checklist. Finally, in December, they will be carefully placed into a pretty cloth bag and delivered to Los Ángeles Malagueños de la Noche ready for Kings’ Day on January 6th when the children get their presents.

Their other project for homeless people is the sponge bags, another of Janet’s brainwaves. We gave out 180 last year and they hope to match that this year. A sponge bag, each with a flannel, toothbrush, toothpaste, shampoo, and a bar of soap. Two years ago (or was it three now?) I distributed forty of them at the homelessness day centre and was desperately moved by the delighted gratitude shown by the attendees on receipt of something so simple that we all take for granted.

Back in the church hall Mary made tea and I sliced a cake I had brought as a very  inadequate thank you to these stalwarts. I gave them the message of gratitude from the Chair of Los Ángeles Malagueños, and described for them how the Kings’ Day toy distribution happens, and how lots of children write their letters to the Kings in advance, and how we try to find toys that match their wish-lists. Many of dolls made here by this group get put in the bags for those children. (See Sunburnt Angels for the story). inadequate thank you to these stalwarts. I gave them the message of gratitude from the Chair of Los Ángeles Malagueños, and described for them how the Kings’ Day toy distribution happens, and how lots of children write their letters to the Kings in advance, and how we try to find toys that match their wish-lists. Many of dolls made here by this group get put in the bags for those children. (See Sunburnt Angels for the story).

I was useless. And they were all so skilled. An actual hairdresser was washing  and combing the dolls’ hair! I was captivated by the bags of teeny tiny shoes that someone else had bought and donated. But it was a fiddly job, finding shoes to fit each doll! Why are these things not standardised? I managed to put a dress on one doll and then to find her a pair of shoes. The team explained about different brands of dolls, and the problems of the angle of the foot and its lack of flexibility. I decided that my minimal talents lie elsewhere, so I collected up and combing the dolls’ hair! I was captivated by the bags of teeny tiny shoes that someone else had bought and donated. But it was a fiddly job, finding shoes to fit each doll! Why are these things not standardised? I managed to put a dress on one doll and then to find her a pair of shoes. The team explained about different brands of dolls, and the problems of the angle of the foot and its lack of flexibility. I decided that my minimal talents lie elsewhere, so I collected up  the mugs and went off to be vaguely useful by washing up, now that the sink was no longer acting as a hairdressing salon. As I disappeared into the kitchen I heard a frustrated cry of “Has anyone got any knickers? This is a lovely dress but you can see straight through it!” Undeterred, the team rifled through the boxes of tiny accessories, and knickers were produced. the mugs and went off to be vaguely useful by washing up, now that the sink was no longer acting as a hairdressing salon. As I disappeared into the kitchen I heard a frustrated cry of “Has anyone got any knickers? This is a lovely dress but you can see straight through it!” Undeterred, the team rifled through the boxes of tiny accessories, and knickers were produced.

Especially at the moment, TV documentaries and so-called “reality” shows like to depict us as “expats” lounging around our swimming pools (in truth, few of us have them) or huddling together in our bowls clubs (I’ve never set foot in one). The actual reality might be too boring for them. The actual  reality was there in that church hall that afternoon. Kind people, not seeking recognition, living in their new country, driving around collecting donations of toothpaste or dolls, crocheting and sewing through the winter, and spending a sociable but intensive afternoon once a month creating Christmas magic for children and families they will never know. reality was there in that church hall that afternoon. Kind people, not seeking recognition, living in their new country, driving around collecting donations of toothpaste or dolls, crocheting and sewing through the winter, and spending a sociable but intensive afternoon once a month creating Christmas magic for children and families they will never know.

#NingunNiñoSinRegalo

#NoChildWithoutAPresent

© Tamara Essex 2019 http://www.twocampos.com

DONATIONS GRATEFULLY RECEIVED!

We sometimes sell some donated items to raise money to buy small missing items for the doll project or the sponge bag project. In addition, the general needs of Los Ángeles Malagueños de la Noche are unending. Donations can be sent direct to them – here are the details for the account for Los Angeles de la Noche (this is their international IBAN number which receives donations in any currency!):

Unicaja: ES60 2103 3034 42 0030013426

PAYPAL OPTION NOW AVAILABLE!

Simply go into your own Paypal account and for the recipient, put the email address: tesoreria@angelesdelanoche.org

1

Like

Published at 6:12 PM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 6:12 PM Comments (0)

180 - Settled?

Thursday, September 5, 2019

There was a nurse on my flight home to Málaga. A Spanish nurse, working in a GP surgery in Dorset. British husband, dual-nationality totally bilingual daughter. We’d been chatting in the queue about the newish Ryanair rules requiring us to jam our handbags INSIDE our cabin bags, just for passing through the gate before boarding. ¡Qué pena! What a pain. She was flying to Spain for just a couple of days, to collect her daughter from the Spanish grandparents in Granada province to bring her back for the new school term.

Inevitably THAT subject came up. The other Spanish nurse at her surgery had already packed up and left the UK. She hadn’t wanted to go through the palaver of applying for Settled Status because she’d been out of the UK for a year recently when her abuela(grandmother) had been ill, and she already  knew that would cause hiccups in her application. This woman, Almudena, had put her application in but had not heard the outcome yet. She was a bit worried, as she’d applied quite early (the Settled Status application system was piloted first in the NHS before being rolled out) so she thought there might be a problem. Without it she was worried she wouldn’t be able to travel in November. I’d read similar concerns on the Facebook forum for Spanish people in the UK. I have no idea whether their concerns were justified or not – but when you have those uncertainties, you daren’t make plans. knew that would cause hiccups in her application. This woman, Almudena, had put her application in but had not heard the outcome yet. She was a bit worried, as she’d applied quite early (the Settled Status application system was piloted first in the NHS before being rolled out) so she thought there might be a problem. Without it she was worried she wouldn’t be able to travel in November. I’d read similar concerns on the Facebook forum for Spanish people in the UK. I have no idea whether their concerns were justified or not – but when you have those uncertainties, you daren’t make plans.

The young woman in front of us turned to listen. Her t-shirt bore a feminist slogan in Spanish. She joined in the conversation, almost spitting her answer. “No voy a pedirlo”, she said, her upper lip curling slightly. “I’m not going to apply. It’s not fair. I went there to work, cleaning up their grandmothers so they don’t have to. If they don’t want me there then I’ll leave. I can work anywhere.” The young woman in front of us turned to listen. Her t-shirt bore a feminist slogan in Spanish. She joined in the conversation, almost spitting her answer. “No voy a pedirlo”, she said, her upper lip curling slightly. “I’m not going to apply. It’s not fair. I went there to work, cleaning up their grandmothers so they don’t have to. If they don’t want me there then I’ll leave. I can work anywhere.”

“I thought the same” said Almudena. “I was furious. I made my life there, I had the right. Just because their stupid country made a stupid decision, why should they turn MY life upside down?” The presence of the feisty one had brought out more of Almudena’s frustration. Talking just to me she had only had positives to say about Britain. She had called it “home”. But the anger had been there, simmering very close to the surface. Now it was “their stupid country”. I didn’t object. How could I?

The young care-worker said she might go to Italy next as someone from her village was already working there, and she’d like to add Italian to her impressive  list of languages. Though other EU countries don’t go out actively trying to recruit nurses and care-workers in Spain. Only the UK does that. Ironic, really. The Home Office refuses Settled Status on some technicality for a nurse with 25 years of experience in the NHS (having been educated and trained at Spain’s expense), and at the same time the NHS advertises in the Spanish nursing press and general newspapers to encourage more, to replace those who are exiting. Meanwhile, the Spanish health service welcomes the returners with open arms. They now speak perfect English (useful for dealing with British patients in Spanish hospitals who don’t have the language) and they have worked in a variety of settings in the UK with a wide range of nationalities. Excellent attributes! list of languages. Though other EU countries don’t go out actively trying to recruit nurses and care-workers in Spain. Only the UK does that. Ironic, really. The Home Office refuses Settled Status on some technicality for a nurse with 25 years of experience in the NHS (having been educated and trained at Spain’s expense), and at the same time the NHS advertises in the Spanish nursing press and general newspapers to encourage more, to replace those who are exiting. Meanwhile, the Spanish health service welcomes the returners with open arms. They now speak perfect English (useful for dealing with British patients in Spanish hospitals who don’t have the language) and they have worked in a variety of settings in the UK with a wide range of nationalities. Excellent attributes!  But, sadly, attributes which are not valued in the UK, in our rush to either actively eject these workers or simply ramp up the Hostile Environment so they leave of their own accord. But, sadly, attributes which are not valued in the UK, in our rush to either actively eject these workers or simply ramp up the Hostile Environment so they leave of their own accord.

We filed on board. After an acquaintance of a mere half hour, Almudena hugged me and wished me a good flight and a good continued life in Spain. I wished her luck with her Settled Status and reminded her to join the Facebook group for Spaniards facing Brexit. A couple of hours later we landed in Málaga and I headed home to Colmenar. Yes I still do keep “a foot in two campos”, and I love my visits to Dorset to see my lovely friends. But I am settled in Spain. I feel as though my “status” is that of “settled”. My adopted country is being  kinder to me than my birth country is to Almudena and countless like her. I shall go back in October for the big protest march. I’ll march for Almudena too, and for all the nurses, care-workers, shop staff, plumbers, mothers, partners, neighbours and friends who don’t want to leave, don’t want to be pushed out, don’t want to feel so UN-settled. kinder to me than my birth country is to Almudena and countless like her. I shall go back in October for the big protest march. I’ll march for Almudena too, and for all the nurses, care-workers, shop staff, plumbers, mothers, partners, neighbours and friends who don’t want to leave, don’t want to be pushed out, don’t want to feel so UN-settled.

© Tamara Essex 2019 http://www.twocampos.com

5

Like

Published at 1:36 PM Comments (7)

5

Like

Published at 1:36 PM Comments (7)

179 - Escaping the Heat

Thursday, August 29, 2019

Forty degrees and higher. Really, that is too much. The rhythm of the day changes to suit the temperature. At the hottest time, after a lazy late lunch, it’s time for a siesta. Late at night, after midnight and into the small hours, it is finally cool enough outside to sit on a kitchen chair on the slope of our little street and share some comfortable time with the neighbours, catching up with the minutiae of life.

Fifty of us from the village (49 Spaniards and me!) escaped the heat a week ago and went on the holiday organised by the town hall, travelling up north to Galicia where not only are the temperatures 12-15°C lower, but there is even that blissful possibility of a little light rain! As always, the town hall staff had organised a cracking programme covering all the sights of the area, but (also as always) every day was packed, from early breakfast in the hotel through three or even four  different visits in a day, and ending with late nights and singing in the bar. Every village has a Pedro, and ours entertained us with songs and jokes long into the night. Even better (or maybe worse!), this year our hotel was in a pueblo celebrating its annual feria. Despite having celebrated our own feria the week before, some of our group sallied forth to participate; I felt my age and retreated to bed, the music and the fireworks close enough to enjoy but far enough away not to keep me awake. different visits in a day, and ending with late nights and singing in the bar. Every village has a Pedro, and ours entertained us with songs and jokes long into the night. Even better (or maybe worse!), this year our hotel was in a pueblo celebrating its annual feria. Despite having celebrated our own feria the week before, some of our group sallied forth to participate; I felt my age and retreated to bed, the music and the fireworks close enough to enjoy but far enough away not to keep me awake.

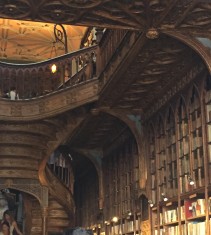

We had excursions to Santiago de Compostela (bagpipe music in the streets!), Pontevedra, Combarro, Cambados, Monte de Santa Tecla, several bodegas, a river cruise, and innumerable castles and  cathedrals. Galicia had a, well, an “uncomfortable” history with the English, and possibly a dozen times our tour guide made reference to the marauding English, the treasures stolen by the English and now in the British Museum, and the damage done by English pirates. I did a lot of apologising! Then, by way of a change, we crossed the border into Portugal and visited Oporto. The official city guide there had a much more positive view of Great Britain and spoke glowingly of the two countries’ relationship, the impact of various British people on the growth of the city, and finally led us to an ancient bookshop, Librería Lello, with cathedrals. Galicia had a, well, an “uncomfortable” history with the English, and possibly a dozen times our tour guide made reference to the marauding English, the treasures stolen by the English and now in the British Museum, and the damage done by English pirates. I did a lot of apologising! Then, by way of a change, we crossed the border into Portugal and visited Oporto. The official city guide there had a much more positive view of Great Britain and spoke glowingly of the two countries’ relationship, the impact of various British people on the growth of the city, and finally led us to an ancient bookshop, Librería Lello, with  twisting wooden staircases, that had been on the brink of failing fifteen years ago, until in a radio interview one day J K Rowling mentioned how this quirky bookshop had inspired elements of Hogwarts and of Diagon Alley, when she had worked in Oporto for a year teaching English. On the point of closure, within ten days of the interview the bookshop began to receive a trickle of visitors which rapidly turned into a flood. Within two months they had to institute a queuing system, and two more months later, a charging system – 5€ refundable against the purchase of any book. To this day, tickets need to be bought in advance, and the 200-strong queue is fenced on the other side of the road, as the bookshop’s success was threatening that of the neighbouring shops. The magic of Harry Potter pops up in extraordinary places! twisting wooden staircases, that had been on the brink of failing fifteen years ago, until in a radio interview one day J K Rowling mentioned how this quirky bookshop had inspired elements of Hogwarts and of Diagon Alley, when she had worked in Oporto for a year teaching English. On the point of closure, within ten days of the interview the bookshop began to receive a trickle of visitors which rapidly turned into a flood. Within two months they had to institute a queuing system, and two more months later, a charging system – 5€ refundable against the purchase of any book. To this day, tickets need to be bought in advance, and the 200-strong queue is fenced on the other side of the road, as the bookshop’s success was threatening that of the neighbouring shops. The magic of Harry Potter pops up in extraordinary places!

On our final night the hotel organised a traditional Galician ritual, una queimada. A witch, a burning cauldron, scary Celtic music, atmospheric chanting, all to make the local fruited alcohol, la queimada, which is like a very strong mulled wine or punch. An unforgettable finish to the holiday. On our final night the hotel organised a traditional Galician ritual, una queimada. A witch, a burning cauldron, scary Celtic music, atmospheric chanting, all to make the local fruited alcohol, la queimada, which is like a very strong mulled wine or punch. An unforgettable finish to the holiday.

Exploring the rest of this enormous, beautiful country is such a joy. I love my “escapadas”, whether on my own, visiting friends in other parts of Spain, travelling  with friends, or these frenetic holidays with my village. Each style of travel has its charm and its advantages. The trips with this lively, noisy, kind bunch of people that I am delighted to call my neighbours, provide me with an intensive week-long language immersion. They might leave me exhausted and in need of another holiday in order to recover, but they further deepen my ties with this special little village which has embraced me as much as I have embraced it. with friends, or these frenetic holidays with my village. Each style of travel has its charm and its advantages. The trips with this lively, noisy, kind bunch of people that I am delighted to call my neighbours, provide me with an intensive week-long language immersion. They might leave me exhausted and in need of another holiday in order to recover, but they further deepen my ties with this special little village which has embraced me as much as I have embraced it.

As the August heat continues (surely hotter even than last year?), I escape again and fly to Dorset for a week of visiting friends in more manageable temperatures. I messaged a friend asking what the weather was going to be like. Her reply pinged onto my phone: “The weather is going to be lovely over the Bank Holiday weekend”. A minute later the phone pinged again: “Well, lovely for Dorset”. It’s all relative.

© Tamara Essex 2019 http://www.twocampos.com

2

Like

Published at 7:54 PM Comments (1)

2

Like

Published at 7:54 PM Comments (1)

178 - Big Blue Skies - Small Cloud

Wednesday, August 7, 2019

Back when I worked (oh how long ago it seems, now!) I was up with all the jargon. Words like social inclusion, stakeholders, outcomes and future-proofing. The charity sector’s version of management-speak. And yet all of a sudden I am “future-proofing” all sorts of aspects of my life! And it feels quite serious.

Purely by luck rather than any sort of forward planning my house will, I think, do me well into old age. Watching friends both in Spain and the UK needing to make adaptations or move to more manageable accommodation or nearer essential  services triggered a very serious walk around my house, looking at it dispassionately. Will it work for my later years? Yes, I think so. There’s a downstairs bedroom with easy access to the bathroom. At a pinch, a stairlift might even be possible. I’m in the village centre, easy access to shops, buses, neighbours etc. And, as importantly as any of those practicalities, it’s where I want to be. services triggered a very serious walk around my house, looking at it dispassionately. Will it work for my later years? Yes, I think so. There’s a downstairs bedroom with easy access to the bathroom. At a pinch, a stairlift might even be possible. I’m in the village centre, easy access to shops, buses, neighbours etc. And, as importantly as any of those practicalities, it’s where I want to be.

A couple of friends have thought that I’m being premature. But a stroke, a fall, a broken hip, a debilitating illness, these things can strike at any time. We all know that. We’ve all seen it. And how much harder is it to move when in the middle of any of those problems?

So the house will suit me until they carry me off to a nursing home or to the crematorium. Yet all the while, all the small changes I can make now, all the slightly bigger changes that I can envisage and budget for further down the line, the over-arching question-mark is still there, hanging there, that uncertainty, probably manageable for most of us, probably not for some. Is there any point in planning for the future while the dark cloud of the unmentionable B-word hovers over us?

In the meantime, a big part of future-proofing continues to be improving and perfecting the Spanish language. Because only through the language are deep friendships made, and only through deep friendships are real roots put down. So I carry on studying, carry on practising with friends, including with Jose, my inter-cambio language partner since I arrived (and always my best resource). In the meantime, a big part of future-proofing continues to be improving and perfecting the Spanish language. Because only through the language are deep friendships made, and only through deep friendships are real roots put down. So I carry on studying, carry on practising with friends, including with Jose, my inter-cambio language partner since I arrived (and always my best resource).

Yet all the while, all the time the language improves, that cloud still hangs there. The hours and the money on lessons … we lack the certainty to be 100% sure that it’s all worth while. The brain says “of course it is!” and I continue to actively help and encourage other British people wanting to learn Spanish. But deep inside the niggle is there. Learning and improving the language assumes a future here. Despite the clear blue Spanish summer sky, we are never without that cloud. It just hangs there.

So there is not just the normal future-proofing that everyone should be on top of – updating the will, ensuring that loved ones are protected – five million of us have extra future-proofing to do, we have to do Brexit-proofing. Of course, everyone has to, not just those of us who exercised our Treaty rights to live in a different country. Everyone needs to prepare (just like the leaders of the Leave campaign, most of whom have demonstrated their patriotism by moving trust funds, wealth management companies, or their manufacturing base out of the UK). But we lesser mortals have to plough through a list of additional tasks, whether we are citizens of EU27 countries living in the UK, or UK citizens living in one of the EU27 countries.

Future-proofing our residency cards. After five years of official residency in Spain we are entitled to change them for a card that has the word “permanent” on it. Only a small change, but the “guidance in case of No Deal” that the Spanish  government has prepared for us sets out that people without “permanent” residency may have more hoops to jump through in the future when we become “Third Country Nationals” and change to a different, non-EU identity card. When we have fewer rights. When we don’t, in fact, have the RIGHT to be here, we only have “permission”. government has prepared for us sets out that people without “permanent” residency may have more hoops to jump through in the future when we become “Third Country Nationals” and change to a different, non-EU identity card. When we have fewer rights. When we don’t, in fact, have the RIGHT to be here, we only have “permission”.

Future-proofing our driving licences. I finally got round to exchanging my driving licence for a Spanish one. In case of No Deal. Because we don’t know. Because so many things remain unclear. They have taken my British one, given me a temporary one, and I check the postbox each morning awaiting the Brexit-proof Spanish licence (which will need explaining when I drive in the UK!).

Health care. The big one. Frankly, all I can do is check my savings account and my ISA and hope and assume that there is enough in there to take care of me in the case of No Deal. You move to another EU country safe in the knowledge that the 300,000 British pensioners who have done the same before you, have their healthcare funded by the UK (from the taxes paid throughout our lives) paid to our new host country through the EU-wide agreement. Without a Deal, many will reluctantly return to the UK, unable to pay for healthcare and medications out of a pension which every month buys fewer euros. Pensioners faced with bills of 1,000€ a month, some even more, just for medications. Those of us lucky enough to have come out here with a bit of a cushion check it nervously, wondering if it will last. The enormous blue sky stretches from the village to beyond the mountains. And in the middle, unseen by everyone except British people, hangs that cloud.

I went on one of my little road-trips last week. Una escapada. A lovely few days,  meeting old friends and new. Back via a village that’s not too far from me, Torrox Pueblo, which traditionally hangs umbrellas in the main square to provide spots of shade and a bit of colour. Lovely! Colourful. Photogenic. From nowhere, between the coloured brollies, up in the blue Spanish summer sky, a white cloud drifted across. meeting old friends and new. Back via a village that’s not too far from me, Torrox Pueblo, which traditionally hangs umbrellas in the main square to provide spots of shade and a bit of colour. Lovely! Colourful. Photogenic. From nowhere, between the coloured brollies, up in the blue Spanish summer sky, a white cloud drifted across.

The cloud is always there.  Life goes on, we future-proof, and as far as we can we Brexit-proof. But life is in limbo for five million people about to lose our rights. There’s a cloud that doesn’t go away. Never a day or even an hour goes by without it forcing its way, uninvited, into our thoughts. And a coloured umbrella won’t be enough to protect us. Life goes on, we future-proof, and as far as we can we Brexit-proof. But life is in limbo for five million people about to lose our rights. There’s a cloud that doesn’t go away. Never a day or even an hour goes by without it forcing its way, uninvited, into our thoughts. And a coloured umbrella won’t be enough to protect us.

© Tamara Essex 2019 http://www.twocampos.com

1

Like

Published at 4:28 PM Comments (17)

1

Like

Published at 4:28 PM Comments (17)

177 - Forty Days

Sunday, February 17, 2019

Forty-four days.

I go for my morning walk, my feet heading automatically to the Enchanted Place. The almond blossom is just finishing, and the grass smells fresh. The view is clear,  across to the rocky outcrop that so dominates the village, across to our big mountain, with just a touch of snow on its peak, down to the neighbouring village, and back through the frame of the almond trees to the village that I call home. I shake off the worries, the cloud that hangs over, and turn back, retracing my steps and round to the bakery where Gloria puts my bread roll in a bag as I enter, without waiting for me to ask. across to the rocky outcrop that so dominates the village, across to our big mountain, with just a touch of snow on its peak, down to the neighbouring village, and back through the frame of the almond trees to the village that I call home. I shake off the worries, the cloud that hangs over, and turn back, retracing my steps and round to the bakery where Gloria puts my bread roll in a bag as I enter, without waiting for me to ask.

Forty-three days.

February. The skies are blue but indoors it is chilly. I light the fire after lunch and settle down to some Spanish homework. No more exams for me, but I keep going to classes and there’s always more to learn. Suddenly in the Spanish article I’m reading the word referéndum appears and at the same moment a log slips and I jump. I glance out of the window and it seems greyer. The flames flicker but there’s a chill.

Forty-two days.

On Facebook I click on a group I belong to, of Spanish people living in the UK. At first I joined to help me get used to casual badly-written Spanish, and in case I could help with advice. Now I stay to understand the processes they face, in case we will face something similar here. It seems inhuman, excessively-demanding, and every day on the group there are awful stories of people with 25 years or more in the UK being refused “Settled Status” because they can’t PROVE they have lived there (including someone who has worked consistently for a Local Authority). A few weeks ago the Prime Minister lifted the £65 charge. As so often, she missed the point. The point is that they, like me, moved because they had the right so to do. As long as we met the fairly basic requirements (of working or being self- sufficient) we had the RIGHT to live elsewhere. What the EU citizens in the UK are currently having to do is ASK permission. Permission which can be … and is being … refused, apparently randomly. This small Facebook group of 5,400 Spaniards log on each morning to share their happiness at a successful application, their distress at a refusal, their confusion because applications must be made through an App but it only works on Android phones. The UK’s Home Office trips them up at every turn, and they turn to the group for advice and for solace. sufficient) we had the RIGHT to live elsewhere. What the EU citizens in the UK are currently having to do is ASK permission. Permission which can be … and is being … refused, apparently randomly. This small Facebook group of 5,400 Spaniards log on each morning to share their happiness at a successful application, their distress at a refusal, their confusion because applications must be made through an App but it only works on Android phones. The UK’s Home Office trips them up at every turn, and they turn to the group for advice and for solace.

Here in Spain we do the same. Following parliamentary votes, party divisions, British Consulate press releases and online updates. Following them slavishly, following the advice and support groups that exist for British people in each of the EU countries. We all have friends who haven’t quite got all the required paperwork in place, and we worry for them. Those of us with official residency here will have to do what the Spanish in the UK are doing, we will have to ask permission to stay. Can they refuse? Yes, though we obviously hope our adopted host nation continues to be more welcoming to us than the UK is to the Spanish nurses, architects and bar-workers whose right to live there has changed to requesting permission.

Forty-one days.

I’m out with Pilar and Ana in Málaga. A coffee, a film, drinks and a few tapas. Gossiping, relaxing. They avoid the subject, though they are following it closely too, worried for me.

A couple of weeks ago it was announced that pensioners living in EU countries would only get the normal inflationary uplift one year more, then their pensions would be frozen at that level. Last week it was announced that pensioners living in EU countries were no longer entitled to NHS care if they visited the UK. There is now clarity about the restrictions on people without official residency. All those second-home owners, part-timers, the winter “swallows”, many of them elderly, who sank their savings into their much-loved Spanish holiday-home. 90 days in 180 days, but that’s for the whole Schengen area, not just Spain, so those who liked to take a week or two to drive down, exploring France on the way, will have to start spreadsheets, counting, rationing their days. Their right to spend time in their own home is suddenly restricted, suddenly diminished.

Forty days.

I come out of the oldies’ gym in the village, waving goodbye to the women and jumping in my car to head down the autovía. In Málaga the city is gearing up for Carnaval. The lights are up, large and small stages pop up in the squares and side-streets. The cycle of another year is underway. After Carnaval it’ll be Semana Santa, then feria, and so it goes on. After six years here I still love each of those events. I’d miss them. I come out of the oldies’ gym in the village, waving goodbye to the women and jumping in my car to head down the autovía. In Málaga the city is gearing up for Carnaval. The lights are up, large and small stages pop up in the squares and side-streets. The cycle of another year is underway. After Carnaval it’ll be Semana Santa, then feria, and so it goes on. After six years here I still love each of those events. I’d miss them.

It’s not that I won’t be able to stay. I will hand in my little green residency card, that I was so proud of in 2013 when I got it from the police station, and I will ask permission to stay. I have no doubt it will be granted. But I still have to ask permission. They will grant it, I’m sure, but it is not a right any more. So it feels different. It ever so slightly changes everything.

I’m unutterably sad. I know I’m lucky, I know I’m protected from the worst impact. Some of my rights are protected by dint of already being here (though the protections become far fewer if there is no deal, and here we are at forty days and we still don’t know). Others cannot follow us, not so easily, not by right. Back there in the UK the impact will be much greater. I know that. We all do. But right now, as I take a mug of tea up onto the terrace and gaze across the village rooftops, as the countdown clicks down to under forty days, the selfish part of me surfaces. I think about the Home Office refusing permission to Spanish people. I think about a friend here worried about not having residency papers. And another friend whose healthcare needs may cut short his Spanish dream. And I think about needing to ask permission to stay, and about the forthcoming general election here in Spain and I worry about what that might mean for my adopted country but also what it might mean for us third-country immigrants who no longer have rights but must ask permission to stay. Permission to stay at home.

© Tamara Essex 2019 http://www.twocampos.com

2

Like

Published at 12:15 PM Comments (9)

2

Like

Published at 12:15 PM Comments (9)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|