150 - Sábado Night's Alright

Friday, July 24, 2015

I’ll never forget the moment. It changed forever the way I looked at art. Madrid, May 2011. The square, Puerta del Sol, was filling with makeshift tents as “Los Indignados”occupied the centre of Madrid. Coming in on the metro from my college accommodation with a Spanish family, I got off one stop early each day to walk through the square, deliver donations of water, milk or juice to the well-organised communal kitchen area. I tried to understand the posters, the protests, and the petitions, before heading to my morning classes at the language school a couple of blocks away. with a Spanish family, I got off one stop early each day to walk through the square, deliver donations of water, milk or juice to the well-organised communal kitchen area. I tried to understand the posters, the protests, and the petitions, before heading to my morning classes at the language school a couple of blocks away.

FOTO: JOSE LUIS ROCA

“Los Indignados” were on the news each night. Our Spanish teachers at the language school commented about what was happening during the daily “culture” session. After class we had free time to explore Madrid, and my feet took me back daily to Puerta del Sol. I didn’t know then that Spain would become my home. I didn’t know that from the chaos and anarchy in the square would emerge a young political party thatwould change the face of Spain’s two-party system. I didn’t know that I was seeing the emergence of the “Occupy” movement that would spread across Europe and end up outside St Paul’s Cathedral that winter. It was an exciting time to be in Madrid, as something was being created at that moment.

And there was more going on in the city. The intensive course was exhausting but there was no time to rest, with all of Madrid to explore. The wonderful Museo El Prado, and theMuseo Reina Sofía. After class I lugged a couple more 8-litre water bottles to the protesters’ kitchen, then walked on through the park to Reina Sofîa, where the 20thC Spanish art is housed. The crowds clustered in front of Picasso’s “Guernica” – huge, dramatic, impressive, violent. As expected. I paid my homage to it and moved away from the hordes into an adjoining room. My mind was overflowing with new Spanish grammar and the activities in Puerta del Sol, and wondering whether I had managed the minimum acceptable time to stand in front of Picasso’s masterpiece.

Around the corner I stopped dead and stared, open-mouthed. I’d seen this painting in prints but nothing had prepared me for the real thing. Sorolla’s “Niños en la Playa”, the sand and the sea shining, glistening, the light on the naked bodies of the three boys was quite extraordinary. I was rooted to the spot. Beneath each boy lying on the beach, you could see how the pressure of their bodies changed the colour and texture of the wet sand, and their reflections added colour and life to the painting. I couldn’t move. I had never looked so closely at the textures and the brushstrokes of a painting. The light and shade on the bodies and on the sand captivated me. From the depths of my memory emerged the Italian word “chiaroscuro” – light and shade. O-level art in Sydney. Suddenly that word had a purpose. A hundred and two years old, the oil paint leapt from the canvas as if it were fresh from the studio. quite extraordinary. I was rooted to the spot. Beneath each boy lying on the beach, you could see how the pressure of their bodies changed the colour and texture of the wet sand, and their reflections added colour and life to the painting. I couldn’t move. I had never looked so closely at the textures and the brushstrokes of a painting. The light and shade on the bodies and on the sand captivated me. From the depths of my memory emerged the Italian word “chiaroscuro” – light and shade. O-level art in Sydney. Suddenly that word had a purpose. A hundred and two years old, the oil paint leapt from the canvas as if it were fresh from the studio.

Four years later and an exhibition called “Días de Verano” (Days of Summer) came to the Museo Carmen Thyssen in Málaga. And it features around 30 Sorolla paintings. Sadly not that particular painting, though many more stunning beach and seaside pictures. This summer I have been a regular visitor to the gallery, popping in to gaze at one or two paintings for ten minutes every few days. The art comes alive in front of you, and the glistening oil is as bright and luminous as ever, unchanging. Four years later and an exhibition called “Días de Verano” (Days of Summer) came to the Museo Carmen Thyssen in Málaga. And it features around 30 Sorolla paintings. Sadly not that particular painting, though many more stunning beach and seaside pictures. This summer I have been a regular visitor to the gallery, popping in to gaze at one or two paintings for ten minutes every few days. The art comes alive in front of you, and the glistening oil is as bright and luminous as ever, unchanging.

And then last week the music, too, came alive in Málaga’s “Palacio de Deportes” when rock legend Sir Elton John hit town. His voice was as strong as ever, though he avoided some of the falsetto sections, and his energy was extraordinary for his 68 years. As we all piled into the aisles to dance to the last few songs, some Spanish lads were singing along to “Saturday Night’s Alright” with a strange mixture of Spanglish lyrics – “Sábado, sábado, sábadonight’s alright, alright alright!”. Elton announced that he planned to tour for only a couple more years, and suddenly it felt even more special to have been there, probably the last time Elton would rock Málaga. The music lives on but a live performance is something special, something more than listening to a CD. To be “hopping and bopping to the Crocodile Rock” along with 6,000 people AND Elton John and his band (and some security guards who had given up and were joining in) is an experience that engages all the senses and a memory that will grow in sentimental value as the legendary rocker approaches retirement. along to “Saturday Night’s Alright” with a strange mixture of Spanglish lyrics – “Sábado, sábado, sábadonight’s alright, alright alright!”. Elton announced that he planned to tour for only a couple more years, and suddenly it felt even more special to have been there, probably the last time Elton would rock Málaga. The music lives on but a live performance is something special, something more than listening to a CD. To be “hopping and bopping to the Crocodile Rock” along with 6,000 people AND Elton John and his band (and some security guards who had given up and were joining in) is an experience that engages all the senses and a memory that will grow in sentimental value as the legendary rocker approaches retirement.

The day after the concert I went back into Museo Carmen Thyssen and gazed at one of my favourites, two children changing into swimsuits. With paintings, time makes no difference. We never needed the artist there to interpret the work. We do that for ourselves, and create our own meanings. Music is a different experience. Being there while the artists sing and play, each performance different in tiny ways, unique. The massive screens showing close-ups of Elton’s hands on the piano, the live audience, the performers’ sweat – it all adds up to something that is of the moment, and can never have the longevity of sculpture, painting, or great architecture. We will still have the CDs, but when the performers are not there to bring it to life, something irreplaceable is lost. The transience adds something to the value of a live concert, yet contradictorily it is the permanence and immutability of great paintings that gives them their value. difference. We never needed the artist there to interpret the work. We do that for ourselves, and create our own meanings. Music is a different experience. Being there while the artists sing and play, each performance different in tiny ways, unique. The massive screens showing close-ups of Elton’s hands on the piano, the live audience, the performers’ sweat – it all adds up to something that is of the moment, and can never have the longevity of sculpture, painting, or great architecture. We will still have the CDs, but when the performers are not there to bring it to life, something irreplaceable is lost. The transience adds something to the value of a live concert, yet contradictorily it is the permanence and immutability of great paintings that gives them their value.

Either way, being here, this summer, in Málaga, has offered some amazing opportunities.

© Tamara Essex 2015 http://www.twocampos.com

2

Like

Published at 11:32 AM Comments (1)

2

Like

Published at 11:32 AM Comments (1)

149 - All You Need is Fruit

Thursday, July 16, 2015

Sometimes you just need fruit. It was the big food distribution day at Los Ángeles Malagueños de la Noche, and the end of lunch service until September. The people in the queue had already queued for breakfast and queued to get a numbered ticket for the groceries, and it was way too hot to be standing in a queue. Even the volunteers were wilting in the heat, and we knew it was nothing like as bad for us as it was for the people in the queue.

We had put up extra shades, extended the covered area, but it was never enough. Especially on groceries day, when the queue was longer than ever.

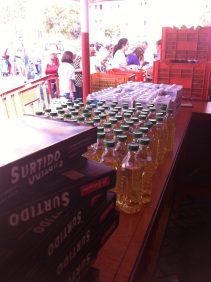

A line of volunteers inside the over-heated portakabin poured olive oil from big drums into half-litre bottles, banging the caps on, and stacking them in crates. Another production line scooped sugar from huge sacks into little bags, tying a tight knot, and tossing them into boxes. At the other end, three more volunteers did the same with powdered drinking chocolate. I started unboxing biscuits and stripping the outer plastic off the triple-packs, and stacking the single-packs in trays. Bags of rice and macaroni were left in the factory boxes, shouldered by the male volunteers and stacked under the tables outside. Milk, a thousand 1-litre cartons of milk, never enough, everyone always asks for more than we can give. A line of volunteers inside the over-heated portakabin poured olive oil from big drums into half-litre bottles, banging the caps on, and stacking them in crates. Another production line scooped sugar from huge sacks into little bags, tying a tight knot, and tossing them into boxes. At the other end, three more volunteers did the same with powdered drinking chocolate. I started unboxing biscuits and stripping the outer plastic off the triple-packs, and stacking the single-packs in trays. Bags of rice and macaroni were left in the factory boxes, shouldered by the male volunteers and stacked under the tables outside. Milk, a thousand 1-litre cartons of milk, never enough, everyone always asks for more than we can give.

The small van arrived and Cisse unloaded boxes of sweets, an added bonus, something to make the day’s distribution marginally less prosaic. The large van arrived from the storeroom, and Diego, Falli and Celestine unloaded big crates of green peppers, tomatoes, aubergines and watermelons. The 44th Al-Andaluz Boy Scouts arrived and began stacking the tables and sharing out tasks. The small van arrived and Cisse unloaded boxes of sweets, an added bonus, something to make the day’s distribution marginally less prosaic. The large van arrived from the storeroom, and Diego, Falli and Celestine unloaded big crates of green peppers, tomatoes, aubergines and watermelons. The 44th Al-Andaluz Boy Scouts arrived and began stacking the tables and sharing out tasks.

La Jefa de la Caseta gave me my task – I was on milk. The queue began slowly so I was able to offer the choice of full-fat or semi-skimmed. Those with children could have the cartons with added calcium. But no second carton, not for anyone. Almost the first sentence I had learned at Los Ángeles had been “Lo siento, solo tenemos lo que tenemos”– sorry, we’ve only got what we’ve got.

Our friendly Policía Local was scrutinising the queue, calming things down, avoiding pushing in. The number system worked well, but people with a long wait wouldn’t go far away, wouldn’t go round the corner into the shade. Too anxious. Too needy. Too hungry. Our friendly Policía Local was scrutinising the queue, calming things down, avoiding pushing in. The number system worked well, but people with a long wait wouldn’t go far away, wouldn’t go round the corner into the shade. Too anxious. Too needy. Too hungry.

The Boy Scouts accompanied the older or more frail people in the queue, carrying their bags as the heavy groceries became too much. On the last table, fruit and vegetables were collected, armfuls of green peppers tipped over the precious groceries, and a watermelon gently resting on top.

The queue was endless. Maybe the knowledge that we weren’t going to be giving lunches for the hot summer months. It was blazing hot, 40°. A pregnant woman was taken out of the queue and brought to the front in the shade. The queue shuffled back a pace or two, uncomplaining. A Boy Scout stripped the plastic from the six-packs of milk to stack them beside me. They ran around, seeing what needed to be done, without being told. They brought jugs of water and plastic cups for the volunteers and for the hot, tired, thirsty people in the queue. Being prepared, putting others before themselves.

Finally the last person filed past. Macaroni, rice, biscuits, sweets, chocolate powder, sugar, milk, oil, vegetables, and a watermelon. There was little left. Four watermelons, so Antonio (our president) brought a big knife out of the caseta and carved slices for the volunteers and the scouts. Nothing had ever tasted nicer. Across the concrete plaza people from the queue were sharing watermelon too. Finally the last person filed past. Macaroni, rice, biscuits, sweets, chocolate powder, sugar, milk, oil, vegetables, and a watermelon. There was little left. Four watermelons, so Antonio (our president) brought a big knife out of the caseta and carved slices for the volunteers and the scouts. Nothing had ever tasted nicer. Across the concrete plaza people from the queue were sharing watermelon too.  We waved and raised a slice to each other and relished the cool melon. Thoughts of “them and us” or “givers and receivers” (had they ever been there) dissolved in the heat. We were all grateful recipients of nature’s bounty, of the generosity of the huge network of collaborators who donate to Los Ángeles, and of the fruits of our labours. We waved and raised a slice to each other and relished the cool melon. Thoughts of “them and us” or “givers and receivers” (had they ever been there) dissolved in the heat. We were all grateful recipients of nature’s bounty, of the generosity of the huge network of collaborators who donate to Los Ángeles, and of the fruits of our labours.

A day later, in the dentist’s chair, Angel explained what he was going to do. Root canal treatment, never a favourite. For once I didn’t try listening to his conversations with the dental nurse. Sometimes, even this obsessive doesn’t want to practise! He gave me quadruple anaesthetic, but I still dug my fingernails into my palm to take my mind off what he was doing. But suddenly I tuned in. “Más fresas” said Angel. More strawberries? “Vale, ¿cuantas fresas?” asked the nurse. “Dame más fresas” repeated Angel. I concentrated. Was this the best time for him to take a fruit break? In the middle of my rather sensitive treatment? If he took a break, it was a short one. Another x-ray to check all was well, and we were done. As he detailed how long I should continue the antibiotics, I remembered the strawberries. “In the middle, why did you ask for strawberries?” I asked him. “Si, fresas” said Angel. Then he laughed and explained that the Spanish word“fresas” doesn’t only mean strawberries – it also means drill-heads! Probably just as well really ….

© Tamara Essex 2015 http://www.twocampos.com

0

Like

Published at 10:49 AM Comments (7)

0

Like

Published at 10:49 AM Comments (7)

148 - Through a Looking Glass

Wednesday, July 1, 2015

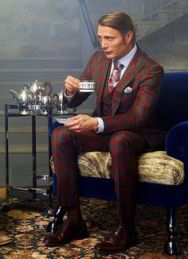

“All English people are like lords and ladies, no?” She wasn’t joking. Perhaps she’s been lucky in the English people she has met, but she is convinced that all of us live in castles and have butlers. She may have been watching the wrong TV programmes.

“There was a mansion in Torremolinos near where I lived as a child” explained Maite in thick Spanish. “Every afternoon when I walked home from school, at exactly 3.15 he would sit at his table in the shade of a tree, and the maid would bring him a tray of tea. I loved to see it, because I know that’s what all English people do.” From this strong childhood memory she had learned three things – that time-keeping is very important to English people, that we all have maids, and that we all drink tea at 3.15. “You drink tea at 3.15, don’t you?” she asked. “Sometimes” I replied. She looked a bit shocked at my slap-dash failure to adhere to my national norms. “But ALWAYS at 8am, without fail” I added, reassuringly. “At EXACTLY 8am?” she asked. “Oh yes, on the dot.” It seemed to comfort her. would sit at his table in the shade of a tree, and the maid would bring him a tray of tea. I loved to see it, because I know that’s what all English people do.” From this strong childhood memory she had learned three things – that time-keeping is very important to English people, that we all have maids, and that we all drink tea at 3.15. “You drink tea at 3.15, don’t you?” she asked. “Sometimes” I replied. She looked a bit shocked at my slap-dash failure to adhere to my national norms. “But ALWAYS at 8am, without fail” I added, reassuringly. “At EXACTLY 8am?” she asked. “Oh yes, on the dot.” It seemed to comfort her.

Jose, my intercambio partner, would perhaps be equally disappointed were he to visit England. He speaks excellent English, partly due to watching the film of “Pride and Prejudice” about a hundred times. He politely greets my friends with “I am delighted to make your acquaintance”, imperceptibly clicking his heels, and proffering a handshake, the other hand behind his back in pure Mr Darcy fashion. He has learned a beautiful, almost forgotten, very refined version of English, of which I rather regret the passing. “It looks very well” he says about a friend’s outfit, or a new car. Instinctively I jump to correct him but stop myself. It’s not wrong, not at all. It’s just that nobody says it any more. Not since the early 1800s.

Some time before his C1 English exam Jose will get to visit London. The range of accents will confuse him, but most of the time he will be wrong-footed by being surrounded by a lack of care for the language he loves, a sloppiness, and a slurring into indistinguishable grunts. And, of course, a complete absence of subjunctives. Before his last exam, I hosted an “English tea-party” with cucumber sandwiches (without crusts, of course), and scones and clotted cream, using a borrowed bone china tea-set. It fitted right into his preconceptions of English people (though the addition of English poetry-readings may have made it an event not TOO frequently replicated in modern-day England). lack of care for the language he loves, a sloppiness, and a slurring into indistinguishable grunts. And, of course, a complete absence of subjunctives. Before his last exam, I hosted an “English tea-party” with cucumber sandwiches (without crusts, of course), and scones and clotted cream, using a borrowed bone china tea-set. It fitted right into his preconceptions of English people (though the addition of English poetry-readings may have made it an event not TOO frequently replicated in modern-day England).

Walking in the Alpujarras recently with a mixed group of English and Spanish friends, one Catalan man couldn’t help expressing his surprise at finding a dozen Brits with reasonable Spanish. “But the English don’t speak more than ‘dos cervezas’ and only shop at their own shops” he kept repeating. Walking along a mountain track, he turned round to stare at us, chatting away with the Spanish contingent, and scratched his head in confusion and delight. It reminded me of the radio interviewer who grabbed me on Kings’ Day at the soup kitchen where I volunteer, to ask why I wasn’t volunteering at a dog rescue “like all the other English”. It’s all prejudice, assumptions, misconceptions, a constructed view of the world that usually gets enough reinforcement to enable people to continue with that view. None of the perspectives are particularly critical, just not wholly accurate. And to me it is fascinating to see the mirror held up to us, to see ourselves as some parts of our host country see us. Walking in the Alpujarras recently with a mixed group of English and Spanish friends, one Catalan man couldn’t help expressing his surprise at finding a dozen Brits with reasonable Spanish. “But the English don’t speak more than ‘dos cervezas’ and only shop at their own shops” he kept repeating. Walking along a mountain track, he turned round to stare at us, chatting away with the Spanish contingent, and scratched his head in confusion and delight. It reminded me of the radio interviewer who grabbed me on Kings’ Day at the soup kitchen where I volunteer, to ask why I wasn’t volunteering at a dog rescue “like all the other English”. It’s all prejudice, assumptions, misconceptions, a constructed view of the world that usually gets enough reinforcement to enable people to continue with that view. None of the perspectives are particularly critical, just not wholly accurate. And to me it is fascinating to see the mirror held up to us, to see ourselves as some parts of our host country see us.

As immigrants, inevitably there are times when one turns to online information groups, providing information about our areas, in our native language. At times it is simply easier than searching the Spanish press or internet for an answer. Similarly, in the UK, Spanish temporary or permanent visitors and workers create Spanish-language information groups, to explain the bizarre British bureaucracy to new arrivals from Spain, and to share moans about the impenetrability of the English culture, language, and people. “Learn English!” they scream at Spaniards seeking work in the UK. People turn to the forums in exasperation, having gone to the town hall to renew their car tax, and having been told to “Go to Swansea” by a town hall secretary “who doesn’t even speak Spanish!” they complain. If nobody else does first, I jump in to explain that they don’t actually have to “go to Swansea”, it can all be done online or at the Post Office. “How odd” they mutter. “Why do the British make everything so complicated and bureaucratic?” “Go to Swansea” by a town hall secretary “who doesn’t even speak Spanish!” they complain. If nobody else does first, I jump in to explain that they don’t actually have to “go to Swansea”, it can all be done online or at the Post Office. “How odd” they mutter. “Why do the British make everything so complicated and bureaucratic?”

On a forum of Bristol-based Spaniards, the discussions were getting heated. “It’s impossible to make friends with the English, they are such a closed society.” “Well how good is your English?” “I can’t improve my English till I have more English friends, and I can’t find work without English either.” “So share a house with English.” “No I don’t want to live with them, they have strange habits.” “Yes that’s true, and housing is SOOOooo expensive here.” “Everything is expensive here!” “And the language is impossible, they talk WAY too fast, and they don’t sound like my teacher did.”

Frequently I read sweeping statements about the English, how ALL English people are setting out to rip off the Spanish, how all English landlords are crooks, how the police let the English break the law but jump on the Spanish …. I don’t get involved, I know they are just frustrated. I have read almost identical comments (often much ruder) from British people in Spain, berating the entire nation of Spaniards. In Bristol the argument usually ended with a Spanish person shouting “Well why don’t you just go back to Spain then, if you hate it so much here?”

So we are all aristocrats, we all drink tea at 3.15, and we all speak beautifully. On the other hand we don’t learn foreign languages, we only ever volunteer in animal charities, we have stupid bureaucratic laws designed to oppress incomers, and we hate Spanish people!

Generalisations. Easy to make. Easy to write in a forum of largely like-minded people, and without thinking condemn an entire nation as if they all share personal characteristics. Reading it and hearing it from the other side is an interesting exercise in how we ourselves are seen. And a useful reminder NOT to criticise or lump everyone together. The internet can, at times, be an excellent mirror on ourselves.

© Tamara Essex 2015 http://www.twocampos.com

2

Like

Published at 1:17 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 1:17 PM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|