53 - First-World Problems

Thursday, April 25, 2013

"Oh you're SOOoooo lucky!" I get told that a lot. Of course I know I'm lucky. What's more, I remind myself every day. Probably every hour. But it's not because I live in two beautiful places and have the freedom to enjoy them. It's certainly not for the reasons most people mean when they say "Oh you're SOOoooo lucky!"

I was born, through none of my doing, into an ethnic group and a socio-economic group which rarely faces any form of discrimination, attack, or even pressure at any real level. The countries where I spend my time have democratic systems, social security systems, and health systems, all of which not only ensure that I am unlikely ever to be left totally starving and destitute, but more importantly ensure the same for everyone else (to a greater or lesser extent). I was not born in a country ravaged by war or starvation. I have chosen to be an immigrant in Spain, but my ethnicity, education, mobility and finances make that comfortable and unremarkable rather than the dangerous situation that faces many immigrants in many countries.

None of that is of my own making, and only a part was of my parents’ making. The wider systemic benefits which have cosseted me all my life are down to luck - the luck of being born in a good time and in a good place, to parents for whom the same was true. It could have been so different.

With that lucky beginning, the confidence and the work ethic instilled by my parents were able to blossom. After my father's premature death, my first job at the age of 17 was as a cub reporter on the Windsor, Slough & Eton Express. A year later an ethical stand-off (oh the sublime arrogance of an teenager with an emerging moral compass!) led to my resignation from journalism and a move to stage management in the London fringe then repertory theatre around the country, tours, and dance festivals. With the horrific arrival of the HIV pandemic I moved into the social care and support of people living with AIDS, then campaigning around broader social care issues, and eventually into 16 years of successful freelance charity consultancy. All of them have been jobs I enjoyed and which made me feel useful. It never occurred to me that I couldn't have a job I loved. It never occurred to me that I might have to do something I hated just to earn a pittance. Most of that comes from the luck of my birth in a developed 20thC western nation combined with the same luck my parents had in THEIR births, enabling them to pass on to me the education, assumptions, and work ethic that I was lucky enough to grow up with. With that lucky beginning, the confidence and the work ethic instilled by my parents were able to blossom. After my father's premature death, my first job at the age of 17 was as a cub reporter on the Windsor, Slough & Eton Express. A year later an ethical stand-off (oh the sublime arrogance of an teenager with an emerging moral compass!) led to my resignation from journalism and a move to stage management in the London fringe then repertory theatre around the country, tours, and dance festivals. With the horrific arrival of the HIV pandemic I moved into the social care and support of people living with AIDS, then campaigning around broader social care issues, and eventually into 16 years of successful freelance charity consultancy. All of them have been jobs I enjoyed and which made me feel useful. It never occurred to me that I couldn't have a job I loved. It never occurred to me that I might have to do something I hated just to earn a pittance. Most of that comes from the luck of my birth in a developed 20thC western nation combined with the same luck my parents had in THEIR births, enabling them to pass on to me the education, assumptions, and work ethic that I was lucky enough to grow up with.

So everything is luck. The timing and geography of birth.

And mostly, the people who say "Oh you're SOOOooooo lucky!" are equally lucky. Mostly, they also come from a similar socio-economic group, and were born in  western democracies with systems of social security and health provision. It is said that if you keep coins for parking in the car, and if there is a handful of change on a mantelpiece or in a drawer, you are amongst the richest 10% in the world - the rest cannot treat money with such casual contempt. You don't need a mansion, a plasma screen TV or a fancy Gaggia coffee-machine to prove wealth, just a pile of coins that you are rich enough not to need right now. western democracies with systems of social security and health provision. It is said that if you keep coins for parking in the car, and if there is a handful of change on a mantelpiece or in a drawer, you are amongst the richest 10% in the world - the rest cannot treat money with such casual contempt. You don't need a mansion, a plasma screen TV or a fancy Gaggia coffee-machine to prove wealth, just a pile of coins that you are rich enough not to need right now.

Everyone reading this has a computer. The majority are probably reading it on an iPad or a decent laptop. Most are in their own homes, from where they are not at risk of eviction. Most will eat well today. We are all rich, compared to half the world who will not eat well today. That alone makes us extraordinary lucky.

What else makes us feel lucky? Clearly family and friends. The people around us who enrich our lives so much. For many that includes animals too. Activities - for some it is their participation in sports, for others it is their art and creativity, the open air, walking in the hills, a rewarding job, reading, travelling, or growing food or beautiful flowers. Special moments when something is achieved.

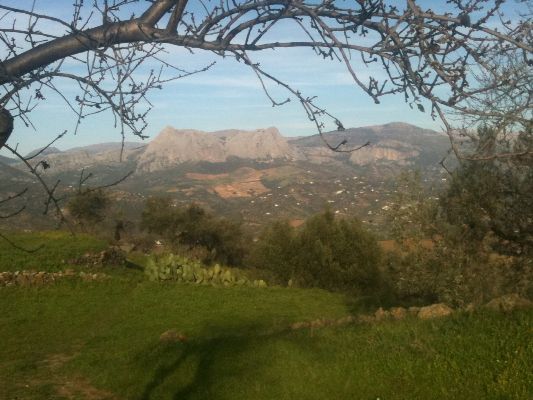

"Oh you're SOOOoooo lucky!" Yes, I know. I remember that every time I wake, healthy enough to enjoy the countryside I see from the window, wealthy enough to put gasolino into the car and to explore Andalucía and my adopted country. I remember that every time I spend time in Dorset in my cosy cottage, lunching with dear friends, shopping at the farmers' market, and visiting London for friends and culture. I remember that every time a friend from the UK is able to jump on a plane and come out to see me. I remember that every time I turn on a tap and clean water comes out. I remember that every time I go to the Enchanted Place and remember my mother and all that she did for me, all that she made me. "Oh you're SOOOoooo lucky!" Yes, I know. I remember that every time I wake, healthy enough to enjoy the countryside I see from the window, wealthy enough to put gasolino into the car and to explore Andalucía and my adopted country. I remember that every time I spend time in Dorset in my cosy cottage, lunching with dear friends, shopping at the farmers' market, and visiting London for friends and culture. I remember that every time a friend from the UK is able to jump on a plane and come out to see me. I remember that every time I turn on a tap and clean water comes out. I remember that every time I go to the Enchanted Place and remember my mother and all that she did for me, all that she made me.

I am so lucky. We all are. Just think how different life could have been for us if we had been born somewhere else, in different circumstances, without the riches we enjoy. Think of that when we are about to moan about a delayed flight, a traffic jam, a new bureaucratic form to fill in, an item out of stock in a shop, or when we lose internet access for a few hours. First-World Problems. So much of the world would love to experience our problems.

If you've read this far, thank you. Now, from you, three things that remind YOU how lucky you are.

© Tamara Essex 2013

0

Like

Published at 11:57 AM Comments (27)

0

Like

Published at 11:57 AM Comments (27)

52 - Inter-Cambio and Getting to Grips with Grammar

Thursday, April 18, 2013

It must be extraordinarily difficult to learn Spanish if you think you don't like learning languages, or if you hate grammar, or don't know what the English words are for different parts of speech. I'm very fortunate to find that I genuinely enjoy the grammatical building blocks of a language, and I love practising and improving my Spanish.

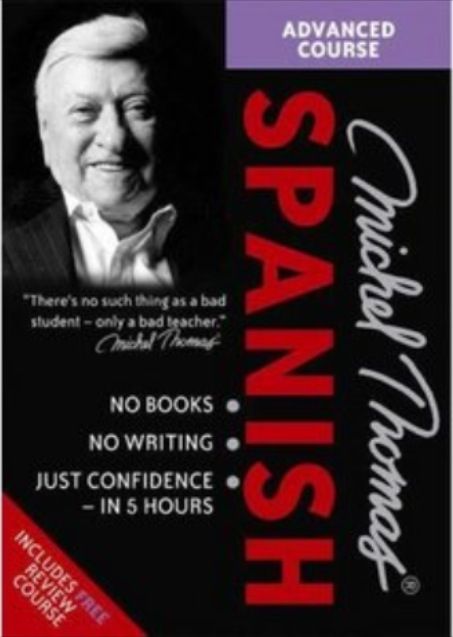

I went to my first Spanish lesson about 7 years ago. Dorset Adult Education, evening classes at the school just behind my house, taught by a Dutch woman. After the first, beginners' year, they didn't run an improvers' course, so my friend  Hazel and I carried on meeting on the same night, at each other’s houses, and used the superb Michel Thomas CDs to work on grammar. With high motivation, and Michel Thomas' help, we sped along. In year three we felt we needed external guidance again, so drove 30 miles each way to Poole Adult Ed each week to do a GSCE class with the irascible Carlos, a Columbian man with a penchant for teaching slightly risqué vocabulary (though to be fair, he did get the WHOLE class though the exam). Year four and no classes to be found, so Hazel and I had a holiday in Sevilla and carried on with Michel Thomas' Advanced Course. Year five and still motivated, we searched for an advanced conversation class and found we had to drive 26 miles to Salisbury College each week where a very strange teacher (this time Bolivian) imposed her views on art or literature, preferring to get HER point across about an artist, rather than encouraging the flow of discussion amongst the students. Hazel and I carried on meeting on the same night, at each other’s houses, and used the superb Michel Thomas CDs to work on grammar. With high motivation, and Michel Thomas' help, we sped along. In year three we felt we needed external guidance again, so drove 30 miles each way to Poole Adult Ed each week to do a GSCE class with the irascible Carlos, a Columbian man with a penchant for teaching slightly risqué vocabulary (though to be fair, he did get the WHOLE class though the exam). Year four and no classes to be found, so Hazel and I had a holiday in Sevilla and carried on with Michel Thomas' Advanced Course. Year five and still motivated, we searched for an advanced conversation class and found we had to drive 26 miles to Salisbury College each week where a very strange teacher (this time Bolivian) imposed her views on art or literature, preferring to get HER point across about an artist, rather than encouraging the flow of discussion amongst the students.

That summer I treated myself to a week-long intensive course in Madrid, coupled with a home-stay in a Spanish family's house. It was an exhausting week but incredibly valuable (and not overly-expensive), and I felt my language was more fluid at the end of it.

Here in Colmenar, as in most towns, the Ayuntamiento puts on free classes. But last year the funding came primarily from the health department, so we had to focus on health-related vocabulary, resulting in repetitive slide-shows of clinic reception areas and hospital departments. Also, the group-leader was not a teacher of Spanish-as-a-foreign-language and was unable to help with complex grammatical questions. A useful service for us immigrants, but it is inevitably difficult for any teacher to deal with a wide range of skill levels and sporadic attendance.

We're fortunate also to have Axalingua in the village. A professional language school run by los hermanos guapos Juan-Mi and Pepe, they offer English and French to Spanish people and Spanish to all the immigrants and tourists. A friend came to stay with me and attended a week-long intensive beginners' course, and rated it very highly. I have attended the fortnightly advanced conversation group and really enjoyed the fun yet rigorous teaching style, and want to attend more regularly. We're fortunate also to have Axalingua in the village. A professional language school run by los hermanos guapos Juan-Mi and Pepe, they offer English and French to Spanish people and Spanish to all the immigrants and tourists. A friend came to stay with me and attended a week-long intensive beginners' course, and rated it very highly. I have attended the fortnightly advanced conversation group and really enjoyed the fun yet rigorous teaching style, and want to attend more regularly.

More recently I have begun a one-to-one inter-cambio with José down in Torre del Mar. So far this is proving to be the best method for language improvement so far. We share the time, half on improving his English and half on improving my Spanish. Through conversation, we establish where each other’s weak points are, and then at the next lesson we each bring a prepared exercise designed to strengthen the vocabulary, grammar, or pronunciation issues identified. José has excellent vocabulary but wants to improve his pronunciation. I am a level or two below him in my Spanish, and he drills me on tenses, as well as helping me use a more natural and colloquial word-order. I'm very lucky to have found an inter-cambio who is as serious as I am, and as interested in getting the grammar right. Other Spanish friends are fantastically useful at correcting me and expanding my vocabulary but of course don't focus on whether we should be using the conditional or the pluperfect subjunctive at any given moment!

On top of that, I try to visit a bar several mornings a week (I know, it's a tough life!) to drink a coffee or juice and read Málaga Hoy, looking at the more formal constructions they use (ridiculously pompous might be another description!) and how it contrasts with chatting with José and others. I have Spanish telly in the lounge and try to watch the news a few times a week, and occasionally something like the Spanish "Quién Quiere Ser Millonario?" can be quite fun. My bedside clock-radio chats rapidly and incomprehensibly to me in Spanish as I fall asleep. On top of that, I try to visit a bar several mornings a week (I know, it's a tough life!) to drink a coffee or juice and read Málaga Hoy, looking at the more formal constructions they use (ridiculously pompous might be another description!) and how it contrasts with chatting with José and others. I have Spanish telly in the lounge and try to watch the news a few times a week, and occasionally something like the Spanish "Quién Quiere Ser Millonario?" can be quite fun. My bedside clock-radio chats rapidly and incomprehensibly to me in Spanish as I fall asleep.

Out of all possible methods, I think my top recommendation for other British people in Spain would be to find a really good inter-cambio language partner (but no, I'm not sharing José!). Or a few private lessons at Axalingua to get you to the level where you can confidently join a class or conversation group. Plus I believe that the Michel Thomas CDs (the Foundation course and then the Advanced course) are unbeatable, whatever level you are. I still keep Advanced CD 4 in the car and just play it over and over, listening to the verb constructions and those awkward "should have", "could have", "would have", "might have" etc etc.

Oh there's an idea! José wants to practice contractions. I foresee a session on "could've" and "might've" coming on!

Deberíamos haber practicado más, entonces habríamos podido entenderlo. We should’ve practised more, then we’d’ve been able to understand it.

Si hubiera hecho los deberes, habría sabido como traducirlo. If I’d done my homework, I would’ve known how to translate it.

© Tamara Essex 2013

0

Like

Published at 8:17 PM Comments (15)

0

Like

Published at 8:17 PM Comments (15)

51 - Bedding In

Thursday, April 11, 2013

Springtime. My first Axarquía spring. A year since I came house-hunting in Colmenar. This week my white-van-man brought my final three boxes, some lamps, and the comfy leather chair from mum's bungalow.

Having got through my first winter I understand more about why Spanish people organise things differently in the cold season and move into a smaller part of their houses. So I'm slowly turning the downstairs bedroom into a study / winter room.  I've got rid of the twin beds and have put in a lovely metal day-bed, comfortable as a sofa for me to lounge on for reading or writing, and a handy spare bed when needed. The sun streams in all year round, and it's a room that's easy to keep warm all day in winter. It's not finished yet but, as in all things, poco a poco, little by little. That room is my project. The leather chair is perfect in there, and the day-bed is really pretty. I've got rid of the twin beds and have put in a lovely metal day-bed, comfortable as a sofa for me to lounge on for reading or writing, and a handy spare bed when needed. The sun streams in all year round, and it's a room that's easy to keep warm all day in winter. It's not finished yet but, as in all things, poco a poco, little by little. That room is my project. The leather chair is perfect in there, and the day-bed is really pretty.

Buying the day-bed didn't go entirely smoothly. I'd picked one in a Segunda Mano (second-hand shop) and paid for it, arranging delivery for a few days later. Then an hour later I saw a prettier one that I fell in love with in another shop - aaargh! I phoned the owner of the first shop, grovelled and apologised and asked if I could change my mind. He was pleasant, and said I could go straight back that morning and have my money back. Phew! But by the time I got there he too had changed his mind and would only offer me a credit note. By then of course I'd paid for the second day-bed. I argued (it's by far the best way of improving your language skills!), but got nowhere and left unhappily with the credit note.

A few days later I met up with my Spanish inter-cambio friend (we meet once or twice a week to help each other improve our language skills). He suggested I use the libro de reclamaciones (complaints book) and checked my draft for accuracy. I plucked up my courage and went back to the shop and submitted my first ever hoja de reclamación (complaint form). It's unlikely to work, because obviously the shop owner is now saying he never offered me the cash refund. Still, as always I turned the experience into an opportunity to practice the language, learning and using different vocabulary in different settings.

Springtime. My first Axarquía spring. The weather is very changeable. The morning walk to the bakery alternates between a sprint in a mackintosh and a glorious languorous stroll bathed in warm sunshine. Slowly unpacking books, putting up hooks and shelves, hanging my print of Zara McQueen’s painting of Castle Hill in Shaftesbury ….. home-making. Thinking about getting the top terrace right. Morning coffee in a bar, reading the Spanish newspaper. Springtime. My first Axarquía spring. The weather is very changeable. The morning walk to the bakery alternates between a sprint in a mackintosh and a glorious languorous stroll bathed in warm sunshine. Slowly unpacking books, putting up hooks and shelves, hanging my print of Zara McQueen’s painting of Castle Hill in Shaftesbury ….. home-making. Thinking about getting the top terrace right. Morning coffee in a bar, reading the Spanish newspaper.  Some good beach days. Getting to know the wonderful city of Málaga. Meals in and out with friends. Language practice. Lunch at a chiringuito (beach cafe). An opportunity to think about how retirement might look and feel. Beginning to realise this might be what it looks like. Some good beach days. Getting to know the wonderful city of Málaga. Meals in and out with friends. Language practice. Lunch at a chiringuito (beach cafe). An opportunity to think about how retirement might look and feel. Beginning to realise this might be what it looks like.

Liking it.

© Tamara Essex 2013

0

Like

Published at 9:13 PM Comments (12)

0

Like

Published at 9:13 PM Comments (12)

50 - Semana Santa - The Splendour and the Silence

Thursday, April 4, 2013

Changeable weather couldn't keep the penitents, the celebrants, the Nazarenos or the tourists away from Semana Santa. In every city, town and village in Spain, people turned out to see the richly-decorated floats and the cofradías (brotherhoods) carrying them. Changeable weather couldn't keep the penitents, the celebrants, the Nazarenos or the tourists away from Semana Santa. In every city, town and village in Spain, people turned out to see the richly-decorated floats and the cofradías (brotherhoods) carrying them.

I have yet to find an area of Spain that does not genuinely believe that their Semana Santa is by far and away the best. Surely they can't ALL be right?

Well maybe they can. They're all so different, yet they're all the same. A full year of preparation, culminating in this most special of weeks and an outpouring of religious (and non-religious) fervour. People crossing themselves and sobbing at the sight of the floats, their long wait finally rewarded. Well maybe they can. They're all so different, yet they're all the same. A full year of preparation, culminating in this most special of weeks and an outpouring of religious (and non-religious) fervour. People crossing themselves and sobbing at the sight of the floats, their long wait finally rewarded.

In the city of Málaga, the largest of the enormous tronos (floats) needs 400 men to carry it. La Virgen del Rocío with her long train is one of the most splendid, while live doves were  released to accompany Las Palomas. Hundreds of thousands of people lined the streets, and every day brought out different tronos, each one a favourite for many people. My photos don’t do justice so I’m crediting people who have done a much better job than I did – these pictures from Málaga are by Emma Munck. released to accompany Las Palomas. Hundreds of thousands of people lined the streets, and every day brought out different tronos, each one a favourite for many people. My photos don’t do justice so I’m crediting people who have done a much better job than I did – these pictures from Málaga are by Emma Munck.

Then in Colmenar Viernes Santo (Good Friday) dawned cloudy but dry. Villagers  anxiously checked the sky throughout the day until it was time for the procession. All day a trickle of people filed past the two tronos in the cofradia headquarters. By 4pm the church was full for Mass. Then at 8pm the floats were ready to emerge. Silence fell outside as the huge doors were swung open and the band began its solemn march. The first float, Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno, followed, carried for the first time solely by women. Behind, anxiously checked the sky throughout the day until it was time for the procession. All day a trickle of people filed past the two tronos in the cofradia headquarters. By 4pm the church was full for Mass. Then at 8pm the floats were ready to emerge. Silence fell outside as the huge doors were swung open and the band began its solemn march. The first float, Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno, followed, carried for the first time solely by women. Behind,  María Santisima de los Dolores emerged, carried by the men of the village. As the procession made its way around the village and up to the church, a reverent silence fell in the streets, broken only by scattered applause and some quiet sobs, almost drowned out by the solemn drumming. Four and a half long hours later the tired women and men returned the tronos to their resting place for another year. María Santisima de los Dolores emerged, carried by the men of the village. As the procession made its way around the village and up to the church, a reverent silence fell in the streets, broken only by scattered applause and some quiet sobs, almost drowned out by the solemn drumming. Four and a half long hours later the tired women and men returned the tronos to their resting place for another year.

From high up here on the hill, we look down into the valley onto the neighbouring village of Riogordo. I tease my friends there, reminding them that we "look down on them" and that they "look up to Colmenar". I'm not sure I can ever  use that line again. Because the most extraordinary experience of Semana Santa was watching "El Paso" in Riogordo, with 600 villagers taking part to act out the Easter story. How amazing for their village to put on such a huge dramatic event every year, and of such high quality. Taking over three hours, the story was acted out across a natural landscape of hillocks creating different areas for the scenes. The ex-stage manager in me couldn't help but be impressed with Judas' suicide (he fell dramatically, to hang from the tree use that line again. Because the most extraordinary experience of Semana Santa was watching "El Paso" in Riogordo, with 600 villagers taking part to act out the Easter story. How amazing for their village to put on such a huge dramatic event every year, and of such high quality. Taking over three hours, the story was acted out across a natural landscape of hillocks creating different areas for the scenes. The ex-stage manager in me couldn't help but be impressed with Judas' suicide (he fell dramatically, to hang from the tree  apparently by his neck), and of course the crucifixion. The music was well-chosen and the central performances were given with passion, while the hundreds of “extras” took their roles seriously (though the occasional first-century villager did whip out an iPhone to grab a photo!). Again, my own photos paled beside Jo McCarthy-Matthews’ dramatic pictures so she gets the credit for the ones used here. apparently by his neck), and of course the crucifixion. The music was well-chosen and the central performances were given with passion, while the hundreds of “extras” took their roles seriously (though the occasional first-century villager did whip out an iPhone to grab a photo!). Again, my own photos paled beside Jo McCarthy-Matthews’ dramatic pictures so she gets the credit for the ones used here.

So perhaps everybody is right. For each city, town and village, their own traditional celebrations are the most important. The Malagueños KNOW that their Semana Santa is the best in Spain. The village of Colmenar KNOWS that whilst theirs is not the biggest it is still the best. And little Riogordo, tucked away in its Axarquía valley, is safe in the knowledge that nobody can ever look down on it again.

© Tamara Essex 2013

0

Like

Published at 2:06 PM Comments (2)

0

Like

Published at 2:06 PM Comments (2)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|