There’s a guy called Dirk Wolz in a small town in Germany who has opened his home to twenty-four Muslim refugees. #Respect. There are few people who would do that. Very few. I couldn’t. I have only one, and that’s been challenging and enriching in equal measures.

He washes up “wrong”. There’s stuff I’ve never seen before in the fridge. I have to put a dressing gown on to go downstairs to the loo in the night. He uses the washing machine almost every day. A coach and horses has been driven through my fiercely-guarded privacy. The night before he was due to move here from the Málaga refugee hostel, at the end of his permitted six months, I cried myself to sleep, dreading the loss of my privacy, and wishing I’d never offered him the spare room.

Yousef is Palestinian, from a small town a couple of hours north-west of Jerusalem. Gentle, cultured, skilled, speaking five languages, he wanted nothing more than to live quietly with his wife and their new baby. But when his life there became untenable and his workplace was attacked, he crossed over through a string of checkpoints, through Israeli territory to Jordan, and then flew to Madrid where he successfully claimed asylum. After four months in the asylum “holding centre” in Madrid, the authorities stuck a pin in a map and despatched him to the refugee centre at Málaga. In a small room with four metal bunks, his room-mates changed every few days. Unsettling. Refugees in Spain get six months in the official hostels, with access to free Spanish lessons, help with their paperwork, their meals, and sometimes job training courses. Yousef tracked down someintercambio groups in Málaga to speed up his Spanish – that’s where we met and became friends, early this year (143 – How the Other Half Lives).

every few days. Unsettling. Refugees in Spain get six months in the official hostels, with access to free Spanish lessons, help with their paperwork, their meals, and sometimes job training courses. Yousef tracked down someintercambio groups in Málaga to speed up his Spanish – that’s where we met and became friends, early this year (143 – How the Other Half Lives).

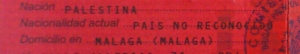

Depending on their country of origin, some refugees find existing networks in Spain, but there are few Palestinians here. So at the end of his time in the hostel Yousef came to Colmenar to share my house. At the town hall, we sat in front of Antonia to register Yousef on the padrón (the local census). Her first request was for his passport. Nope, that’s in Madrid, held by the immigration department (as refugees are not allowed to travel out of the country). Instead he has a document that classifies him as a refugee with permission to work. Antonia had never seen one before – he’s the first refugee on the village padrón. She began to put his details on the computer. Place of birth? Palestina. Nationality? Bizarrely, despite naming his country of birth, his current nationality is printed as “País no reconocido”. Country not recognised. Antonia looked shocked. Yousef looked uncomfortable. It felt like a kick to the stomach. Can you imagine? To have no passport, and just a document that discounts your home, your country? For the millionth time I was thankful for the geographical fluke that provided me with a UK passport.

passport, and just a document that discounts your home, your country? For the millionth time I was thankful for the geographical fluke that provided me with a UK passport.

Two thirds of UN member states officially recognise the State of Palestine, though few EU countries do. Neither the UK nor Spain do so. Antonia didn’t understand – thought it was an error. Tried to write “Palestina” on her computer. It wasn’t recognised. “But of COURSE it exists” she said. “Yes”, said Yousef sadly, “it’s beautiful and it’s my home”. Antonia fell silent. We had nothing we could say. She said she would find out how to register him, and that we were not to worry. I signed the paper to confirm my address as his home.

Back at the house, to celebrate him becoming “un vecino de Colmenar” Yousef knocked up a Palestinian paella. “Is that really a thing?” I asked. “No” he grinned. It was delicious. And during his time in the house he cooked wonderful Arab food for me a few times a week in between odd days of work gathering almonds in the Colmenar campo or driving a fork-lift in a Málaga warehouse. And all the time working towards the day when his wife and child could come to Spain too.

up a Palestinian paella. “Is that really a thing?” I asked. “No” he grinned. It was delicious. And during his time in the house he cooked wonderful Arab food for me a few times a week in between odd days of work gathering almonds in the Colmenar campo or driving a fork-lift in a Málaga warehouse. And all the time working towards the day when his wife and child could come to Spain too.

Each of us can only “rate” our experiences within our own contexts, our own framework. When I first knew him I asked Yousef what his journey was like from Palestine to Madrid. “Terrible”, he had replied. And it was, challenged and delayed at every one of the many checkpoints. Though once he reached Jordan, it was a plane journey to Spain rather than the treacherous routes some have to face. Stressful and facing an uncertain future in the asylum system, but at the same time not much more uncomfortable than any other flight to Spain.

Just before the end of Yousef (1)’s stay in the refugee hostel, I met another Yousef in the room next door. Yousef (2) had travelled overland from Syria with his wife, 6 year-old daughter, and baby boy. The day I was there for coffee with Yousef (1), the new family had transferred to the hostel that morning from the holding centre at Melilla. Their journey, it has to be said, was tougher. Yousef (2) didn’t dare take his two small children the sea route via Turkey and Greece, so they travelled overland via Egypt, Libya, Algeria and Morocco. There, they sat for a month on cardboard staring at the fence – the same fence I’d crossed with confidence a year before, brandishing my UK passport (123 – Passport to Paradise).

I’d crossed with confidence a year before, brandishing my UK passport (123 – Passport to Paradise).

After one failed attempt to cross the fence, where Yousef (2) reached the top but had to jump back down on the same side, the wrong side, when he couldn’t pull his family up, and after watching a friend who had hidden in the boot of a car being found by border patrols, the family put their trust and their entire savings in the hands of a Moroccan “fixer” in Nador. Some are crooks, take the money and disappear. Yousef (2) was lucky. The fixer was honest, he knew which of the Moroccan border police to bribe, and Yousef and his family finally walked through from Morocco into no-man’s land. Nobody had “fixed” the second part of the border crossing, the Spanish side, so the family aimed for a Guardia Civil officer of about Yousef’s age, walked up, and with almost a helpless shrug, said “Well, here we are.”

Perhaps it shouldn’t make a difference, but Yousef’s straight gaze, his wife’s beautiful pleading eyes, their daughter’s uncomprehending face under a head of curls, and the baby boy held out for the policeman to see, made it impossible for the Spanish police officer to refuse this desperate young Syrian family who had come so far through such terrible conditions, from their ravaged country, and who just needed three more yards to gain that foothold on Spanish soil. The Spanish policeman looked back across no-man’s land to the Moroccan policeman. They shared a nod, and the Spaniard jerked his head towards the promised land, and stepped back out of the way. The Syrian family walked to the Melilla immigration centre and applied for asylum. They were held there in an even more crowded holding centre than the Madrid one, and after a few months they too were sent to Málaga.

Spanish policeman looked back across no-man’s land to the Moroccan policeman. They shared a nod, and the Spaniard jerked his head towards the promised land, and stepped back out of the way. The Syrian family walked to the Melilla immigration centre and applied for asylum. They were held there in an even more crowded holding centre than the Madrid one, and after a few months they too were sent to Málaga.

Yousef (1) handed me my mug of coffee and then took the kettle to the newcomers in the room next door so that the baby’s food could be mixed up. Meanwhile, Yousef (2) told me his story. “Are you going to learn Spanish?” I asked him (his English wasn’t bad). “No” he said, “We’re going to Germany”. He’s a high-level engineer working in the gas and electricity industries. And amazingly, a fortnight later when I went back to get one of Yousef (1)’s bags, Yousef (2) had gone. He had contacted the German immigration department, emailed his CV, and they had been sent a permit to travel to Berlin.

So Yousef (1) brought his bags, his strange washing-up habits, his humour and his excellent cooking skills to Colmenar. It turned out that having to put on a dressing gown for a midnight wee wasn’t the end of the world. Sometimes we did our own thing, sometimes we sat companionably by the wood-burner, reading but sharing the odd joke, and sometimes a meal would go on late into the night as we’d discuss religion and politics or he’d tell me about his country, his family, and his hopes. I discovered that actually “the wrong way” is merely a different way and that I could bite back the words before saying “Not that knife for that …”.

for a midnight wee wasn’t the end of the world. Sometimes we did our own thing, sometimes we sat companionably by the wood-burner, reading but sharing the odd joke, and sometimes a meal would go on late into the night as we’d discuss religion and politics or he’d tell me about his country, his family, and his hopes. I discovered that actually “the wrong way” is merely a different way and that I could bite back the words before saying “Not that knife for that …”.

It is odd though – most of us don’t live platonically with other adults after our twenties. Certainly by our fifties we are set in our ways, there’s an unwillingness to change. Different mugs for different drinks, different knives for different things, a way of washing up. It’s not a bad lesson to learn, that “my way” is merely that, and is not the right way or the only way. Either way, I remember with shame my reluctance to share the house with a stranger; weighing up what Yousef has given up and had taken from him  over the past twelve months, what price my privacy? It’s not even close. Anyway, I have learned a thousand things from him and my life is far, far richer for knowing him. And I’m discovering what the stuff in the fridge is, too.

over the past twelve months, what price my privacy? It’s not even close. Anyway, I have learned a thousand things from him and my life is far, far richer for knowing him. And I’m discovering what the stuff in the fridge is, too.

© Tamara Essex 2015 http://www.twocampos.com

NOTE: Both Yousefs gave permission for their stories to be written. Both wanted people to understand more about who refugees are, why they have left their own countries, and how they are no different from any of us. These two Yousefs have children for whom they want what any parent wants – safety, shelter, and a future.

NOTE: Both Yousefs gave permission for their stories to be written. Both wanted people to understand more about who refugees are, why they have left their own countries, and how they are no different from any of us. These two Yousefs have children for whom they want what any parent wants – safety, shelter, and a future.