Some people are easy to like. Belén, for example. Kind, generous, pretty, gorgeous eyes, and she works more than 40 hours a week as a volunteer, cooking and serving meals for homeless people at Los Ángeles Malagueños de la Noche. One of life’s special people. So when it was her turn to need something, dozens of strangers who had never met her were willing to help.

I put the word out amongst my network. We needed to find a double buggy for this special lady. Her second baby is due in December, and anything useful would be an enormous help. Needless to say, the people of the internet responded magnificently. My message box exploded with offers of help. People offered baby clothes, a baby bath, cash to split the cost with me if we ended up buying the buggy. Two professional knitters sent some gorgeous brand new outfits. Two charity shops promised to look out, and offered big  discounts. A fortnight after putting out the call, I drove down to the bar by the reservoir to meet Janet, my long-standing (and long-suffering!) collector, and we transferred the buggy, the baby clothes, plus a dozen sacks of adult clothes for general distribution into my never-quite-big-enough car.

discounts. A fortnight after putting out the call, I drove down to the bar by the reservoir to meet Janet, my long-standing (and long-suffering!) collector, and we transferred the buggy, the baby clothes, plus a dozen sacks of adult clothes for general distribution into my never-quite-big-enough car.

Belén is still working, the month before the baby is due. And it’s heavy, hot work, at Los Ángeles, though the whole team tries to protect her. I drove up as usual at the end of the lunchtime service. The lunch trays were being collected up, washed and stacked.

Belén is still working, the month before the baby is due. And it’s heavy, hot work, at Los Ángeles, though the whole team tries to protect her. I drove up as usual at the end of the lunchtime service. The lunch trays were being collected up, washed and stacked.  The leftover hot noodle dish was being shared out amongst the volunteers, and the tables wiped down. The new indoor dining room is a huge step forward – it looks like any local bar, and is a far more dignified way to serve people than the outdoor queuing and eating that we used to offer. As the last service-user shuffled out of the door, Diego organised a few volunteers to unload my car. The buggy we’d bought from a charity shop was impressive,

The leftover hot noodle dish was being shared out amongst the volunteers, and the tables wiped down. The new indoor dining room is a huge step forward – it looks like any local bar, and is a far more dignified way to serve people than the outdoor queuing and eating that we used to offer. As the last service-user shuffled out of the door, Diego organised a few volunteers to unload my car. The buggy we’d bought from a charity shop was impressive,  with a rain-hood and a removable basket that doubles as a car seat for the new baby. Belén was astounded. As she drove off, exhausted, after her 8-hour shift in a hot kitchen, I spotted the last bag still in my car. I passed it through her car window. Tiny newly-knitted baby clothes, some in blue, some in pink. She squeezed my hand. Hard.

with a rain-hood and a removable basket that doubles as a car seat for the new baby. Belén was astounded. As she drove off, exhausted, after her 8-hour shift in a hot kitchen, I spotted the last bag still in my car. I passed it through her car window. Tiny newly-knitted baby clothes, some in blue, some in pink. She squeezed my hand. Hard.  And whispered “Gracias – gracias de corazón”. She’ll never know quite the scale of “Operation Buggy” nor quite how many people were involved, and she doesn’t need to. But it’s good to know that the “extranjeros” of the Axarquía area can work together to help one of the most deserving people around.

And whispered “Gracias – gracias de corazón”. She’ll never know quite the scale of “Operation Buggy” nor quite how many people were involved, and she doesn’t need to. But it’s good to know that the “extranjeros” of the Axarquía area can work together to help one of the most deserving people around.

And then we come to Norman. Name changed to protect the irredeemably grumpy. He had been living in Málaga town hall’s homeless hostel for a few weeks, but hadn’t come in to the day centre next door so I hadn’t met him. I was waiting outside the British Consulate to organise new passports for him and for a woman I’d been working with for  some months. The social services transport pulled up. Ana, the social worker, waved from inside. Margaret clambered down and gave me a hug, thanking me for helping her do her passport application. A man I didn’t know disembarked slowly using a walking frame. Once he was safely on the pavement I stuck out my hand and greeted him: “Hello, you must be Norman, we haven’t met before. I’m Tamara. Let’s hope we can get your passport application in today.” Norman glared at me. “I’m only here to collect my passport. Whaddya mean, application?”

some months. The social services transport pulled up. Ana, the social worker, waved from inside. Margaret clambered down and gave me a hug, thanking me for helping her do her passport application. A man I didn’t know disembarked slowly using a walking frame. Once he was safely on the pavement I stuck out my hand and greeted him: “Hello, you must be Norman, we haven’t met before. I’m Tamara. Let’s hope we can get your passport application in today.” Norman glared at me. “I’m only here to collect my passport. Whaddya mean, application?”

“Hello Norman, I’m Tamara. Nice to meet you.” I got the sense this afternoon wasn’t going to be a pleasant chat. I was determined that we would start with the basic pleasantries. “I’m not doing no application. I just want my passport”. I gave up, I didn’t want to fight. I explained that we had to do the application that afternoon, and that I was  there because the ayuntamiento (town hall) didn’t have a credit card that could be used for making payment in sterling. Norman turned on the social worker. “You told me I was coming to collect my passport!” he shouted at her in English. Ana has some English but it was obvious that these two had been mis-communicating for a while. “No”, explained Ana, gently, “We’re here to organise that now.”

there because the ayuntamiento (town hall) didn’t have a credit card that could be used for making payment in sterling. Norman turned on the social worker. “You told me I was coming to collect my passport!” he shouted at her in English. Ana has some English but it was obvious that these two had been mis-communicating for a while. “No”, explained Ana, gently, “We’re here to organise that now.”

Norman swore at us and then shouted at the social services driver who had come over to give him his carrier bag. With a sinking feeling, I led the way into the Consulate, through security, and up to the second floor.

“OK, let’s start with Margaret” I suggested. Norman exploded. “I’ve been waiting four months for this ****ing passport!” That inflamed Margaret, who shrieked back at him “You only arrived in the hostel three weeks ago! I really HAVE been waiting months!” Ana looked weary, not fully understanding the content of the argument, but looking as though she’d experienced this before. Behind the glass, the Consulate staff raised their eyebrows, but left me to it.

“Alright then, let’s start with yours, Norman. But be patient with me, I’ve never done an online passport application”. He glared at me. “Well, you’re not much bloody use, are you?” he shouted. He headed for the window to complain to the Consulate staff. “Why can’t you do it? You must have done it a million times!” Jacqui calmly explained to him that they don’t do passport applications, this was a special favour, and that somebody needed to make the payment. She added a suggestion that Norman should perhaps be grateful that someone had volunteered to use their own personal bank card to pay for his passport. He didn’t look as though he agreed,

It took some persuasion to get him to sit down with me at the computer. Every question made him angry. It took a long time. Page one (personal details) successfully completed,  we clicked onto the next section. On the sight of another page of questions, Mr Happy threw another wobbly and swore again, announcing that he couldn’t be ****ing ar*ed. The social worker reminded him that if he wanted to move out of the homelessness hostel and into the residential home in a town west of Málaga, he had to have a residency card in Spain, and to get that he needed an up-to-date passport (his having expired four months before). He sat down again and we slowly completed page two. Moving on to page three, I quickly scanned the forthcoming questions and my heart sank. We were going to have to send his old passport back. I could imagine his reaction.

we clicked onto the next section. On the sight of another page of questions, Mr Happy threw another wobbly and swore again, announcing that he couldn’t be ****ing ar*ed. The social worker reminded him that if he wanted to move out of the homelessness hostel and into the residential home in a town west of Málaga, he had to have a residency card in Spain, and to get that he needed an up-to-date passport (his having expired four months before). He sat down again and we slowly completed page two. Moving on to page three, I quickly scanned the forthcoming questions and my heart sank. We were going to have to send his old passport back. I could imagine his reaction.

Gently, I explained to Norman the remainder of the application process. That the application would go in via the internet, and that we had a page to print off and post to Belfast with his old expired passport. As expected, he exploded. He threw a chair across the Consulate and banged the table. “You ain’t having my ****ing passport!” he shouted and headed for the door. The social worker lost her temper and shouted back at him in Spanish which made him angrier. “I don’t speak ****ing Spanish and don’t shout at me!” he screamed at her. With tempers disappearing on all sides, I was being translator and mediator, while wondering if I would ever get away for my beachside coffee arranged for later.

Calm eventually restored, we stumbled through to the end of the application and reached the payment page. Norman said “Get the woman, she’ll pay.” I explained again that the town hall bank card can’t make payments in pounds sterling, so I was going to use mine. He finally looked straight at me. “Are you a social worker?” “No, I’m a volunteer at the charity next door to the hostel.” “Oh.” Pause. “Well … right. Get on with it, then.”

Payment of £102.36 duly made (including postage to Spain), Norman headed for the door. “Give me your passport” said the social worker. “No” said Norman. “Tomorrow I must post it” said the social worker. “No” said Norman. In between some quite creative swear words, he said he was not handing it over (he used a great many more words than that, but nothing that can be typed here). The consulate staff offered to take his passport if he didn’t want to give it to the social worker. He swore at them. Exasperated, the social worker turned to me and said “Tamara, you must tell him to give it to me.” I took a deep breath. “No” I said. Ana looked surprised. I explained to her in Spanish that Norman was an adult with rights. It is his passport, and in any case he has been sleeping rough for goodness-knows how long and he has never lost it, so if he chooses to, he can keep it one more night. We needed to respect his decision – he was aware of the small risk of it being stolen, and it was his choice.

Norman left. We did Margaret’s application and made the payment in a quarter of the time and I made it to the beach for my coffee. I gave Jose a shortened version of the story. “Why did you do his application?” “Because he needs a passport to be able to get on with the next stage of his life.” “But he should have been grateful, he should have said thank you.”

And that was the crux of it. No, Norman has no responsibility whatsoever to be grateful, nor to say thank you, nor to be pleasant. Whoever said that only nice people deserve help? The government has successfully driven that wedge between people – dividing the “deserving” from the “non-deserving”. And it’s even easier to categorise people who are homeless. To feel sympathy for this one, who lost their job and couldn’t keep up the mortgage payments, but not for this one, who has been in prison for selling drugs. But how often do we get to hear the whole story? The whole depth of what led someone to make the decisions they made?

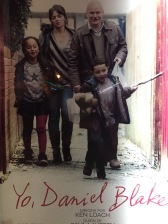

Then a few days later I went to see “I, Daniel Blake”, the excoriating Ken Loach film that shines a light on the government targets set to sanction job-seekers and reduce the  numbers receiving JSA or disability payments. The minister responsible at the time, Iain Duncan-Smith, said that the characters in the film “didn’t ring true”. He had introduced many of the cuts now being suffered by disabled people (so his resignation in protest against the latest cuts “didn’t ring true” to many of us). He and his successor in the DWP spent a long time encouraging the press and the public to divide the nation into “hard-working families” and the “undeserving” on benefits. Widening the gap between the haters and the hated. Giving people someone to blame. If it’s not immigrants, it’s benefits scroungers. Sometimes it’s immigrants on benefits.

numbers receiving JSA or disability payments. The minister responsible at the time, Iain Duncan-Smith, said that the characters in the film “didn’t ring true”. He had introduced many of the cuts now being suffered by disabled people (so his resignation in protest against the latest cuts “didn’t ring true” to many of us). He and his successor in the DWP spent a long time encouraging the press and the public to divide the nation into “hard-working families” and the “undeserving” on benefits. Widening the gap between the haters and the hated. Giving people someone to blame. If it’s not immigrants, it’s benefits scroungers. Sometimes it’s immigrants on benefits.

I don't acceptt the concept of “deserving” and “undeserving”. Everyone deserves food, shelter, an education, the chance to work, respect, dignity, self-determination, and a passport. Nothing in the Human Rights Act says you have to be grateful. The sad truth about Norman is that he has probably always received a bit less of all the essentials because he isn’t enormous fun to be around.  Belén will probably always get her needs met because you only need to meet her and you want to put in that extra effort. And I only needed to mention her voluntary work with Los Ángeles, and people all over Málaga province were queueing up to help (mostly other great hard-working volunteers themselves!). There is no queue to help Norman. He’ll never be the first service-user we think of when a box of shoes or coats comes in, or a carton of biscuits. But he has all the same needs, and all the same rights.

Belén will probably always get her needs met because you only need to meet her and you want to put in that extra effort. And I only needed to mention her voluntary work with Los Ángeles, and people all over Málaga province were queueing up to help (mostly other great hard-working volunteers themselves!). There is no queue to help Norman. He’ll never be the first service-user we think of when a box of shoes or coats comes in, or a carton of biscuits. But he has all the same needs, and all the same rights.

And every time we begin to forget that, the divisive lot win. The haters. The Daily Express, who want us to sneer at the “undeserving poor” so we forget to put attention on the government policies that have put them there. And right now while the papers are full of the High court Brexit decision and now the US elections, the government has sneaked through some more shocking cuts to disabled people’s benefits. When we wonder which of us we shouldn’t be caring about, the wedge is driven further through the remnants of what used to be a kind, co-operative, British society. Politicians divide people, intolerance becomes the norm, hate speech becomes standard, and people stop caring. Every time we think that Norman has some kind of responsibility to say please and thank you, we give more power to the haters and take it away from humanity.

© Tamara Essex 2016 http://www.twocampos.com