Miguel Ángel Fernández, “El Tigre,” a construction worker, is drinking orujo liquor and talking nonstop. He may not realize it, but his life serves a good illustration of the public works frenzy that Spain has experienced in the last few decades.

Fed by European funding, the country has built deserted airports and high-speed rail networks used by very few passengers. Between 2004 and 2013, Spain received €20.56 billion in European money for transportation infrastructure. Of this, €7.45 billion went to the high-speed AVE train.

A prime example of the waste is the series of rail tunnels being built in Pajares, a mountainous area in the northern region of Asturias.

The tunnels, meant for the AVE, have already swallowed up more than €3 billion, and there is no opening date in sight.

El Tigre worked on that project for nearly 10 years. “It was a botched job,” he says. “Construction companies just wanted to get it over with as soon as possible and get their money.”

His story coincides with statements made anonymously by several engineers and geologists who did not want to openly criticize the Public Works Ministry.

“I worked on the Guadarrama tunnels and they came out well,” notes Fernández, 60, in reference to the AVE tunnels going through the Madrid mountains that were built between 2002 and 2007.

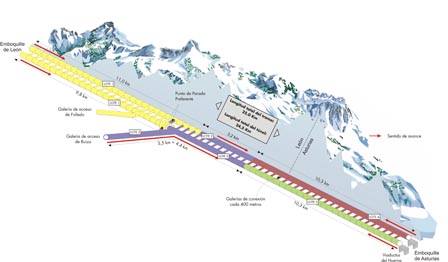

Happy with that experience, in 2003 the ministry awarded the contract for the Pajares project — two 24.6-kilometer-long tunnels, plus several smaller links to connect Asturias and León.

The project had a budget of just under €1.8 billion and involved nearly all of Spain’s major builders: FCC, Acciona, Dragados, Ferrovial, Sacyr, Constructora Hispánica and others.

But the trouble started soon, when water began seeping into the tunnels. “The tunnelling machine kept running into pockets of water,” recalls El Tigre, who is currently unemployed. “I have seen the water pull away containers weighing three tons. But instead of stopping to seal the tunnel properly, we were told to go faster to get out of the water area fast.”

The tunnels were completed in record time. On July 11, 2009, then-Public Works Minister José Blanco attended an event to celebrate the occasion. But the water problems were still there.

El Tigre orders another orujo and notes: “Instead of boring the tunnels eight months ahead of schedule, they should have taken longer, but that was money for the construction companies. Our orders were to finish fast, no matter what.”

A spokesman at Adif, the state-owned railway infrastructure manager in charge of building the AVE tracks, said this was no time to assign guilt, and that other countries have had similar problems with their own projects. He also underscored that the Pajares works represent one of the largest and toughest engineering projects in all of Europe.

Adif commissioned a hydrologic study of the terrain when the work was already underway. However, a study conducted as early as 1986 had already warned that this was a karst area, made up of porous bedrock that lets rainwater seep through. “It is expected that the route will be affected by significant water formations,” read the report.

The various problems led Adif to accept cost overruns that the builders claimed were necessary to complete the project. In the course of a decade, the initial plans were altered 15 times, and price tags reviewed. So far, €2.99 billion has been invested (a cost overrun of €1.2 billion, the same amount that led to the dispute over the Panama Canal construction work). The tracks have not yet been laid, meaning that the cost of the entire project will soar to at least €3.5 billion.

The European Commission, which contributed €724.3 million to the Pajares project, is now asking questions about the overruns. The Anti-Fraud Office has already recommended that the EC ask Spain to return €250 million for allegedly exaggerating the cost of the stone used to build the El Musel port in Gijón.

Pajares is probably the biggest excess in a long list of failed public works projects that include two deserted airports in Castellón and Murcia and the AVE link to Extremadura, with stretches that run to the middle of nowhere that railway technicians have privately dubbed “the AVE of Okavango,” in reference to the African river that empties into the Kalahari Desert.

“It pains me to say this, but Pajares is the greatest failure of Spanish engineering since the Ribadelago dam,” says one geologist, in reference to the ill-designed dam that burst and flooded the village of Ribadelago, in Zamora, in 1959.

See link on the state of the tunnels. They have dried up all the underground water deposits that were supplying the wells and pastures in the region, an ecological disaster.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MX8Pc-7rTRA