When the first full moon of May arrives, the large ‘Bluefin Tuna’ or the ‘Red Tuna’ as it is referred to here, in Spain, migrate from the cold waters of the Atlantic to the warmer Mediterranean in order to reproduce. For years the environmental movement has warned of the danger of extinction of this species due to over-fishing. An agreement on the catch quota does not leave anyone completely satisfied but it is difficult to balance the requirements to preserve resources and preserve a fishing tradition and consumption that dates back thousands of years, especially when certain methods of fishing are far more ecological than others and less aggressive.

International negotiations on Bluefin tuna catches have resulted in less than a 4% increase in quota for this year. The Bluefin tuna is considered ‘ La Pata Negra of the Sea’ in Spain and is one of the most highly prized fish used in Japanese raw fish dishes. About 80% of the Atlantic and Pacific Bluefin tuna is consumed in Japan. Bluefin tuna sashimi is a particular delicacy in Japan and ‘Red Tuna Tartar’ a gastronomic speciality in Cadiz. All tuna were definitely not born equal.

Not all species of the tuna family are equally appreciated from a gastronomic point of view but the Bluefin tuna is the protagonist and the most acclaimed of all is the ‘Red Tuna of Almadraba’ caught on the coast of Cadiz in the Straights of Gibraltar. La Almadraba is an art that dates back 3,000 years and is considered the most ecological and sustainable method used to date, as it permits individual selection and the fish that are set free are not injured in any way.

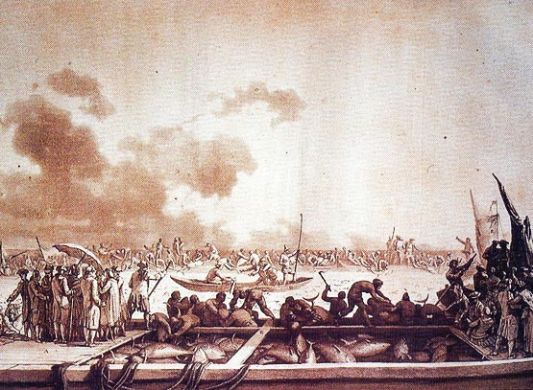

The word Almadraba comes from the Andalusian Arabic word Almadrába, which means a place where one is hit or fights. This technique has its roots dating back to the time of the Phoenicians and even the Romans fed their legions on this migrating tuna. It uses a complex and labyrinthine net system that sinks more than 30 meters deep. It is funnel-shaped and located on the migratory path of the Bluefin tuna, usually near the coast and then pulled up by hand (La Levantá) so the fish come to the surface where they can be selected according to size and the rest are then returned to the Sea (La Bajá).

The fishermen join their boats to form a circle and while all the Bluefin are raging around on the surface, the fishermen are pulling them out of the water by hand, many of them weighing over 200Kg. It is quite a spectacle. This method is truly artisan and is of unquestionable effectiveness and has no consequence to the environment unless too many fish are captured but the Almadrabas are the leading source of information on the control of the species and were the first to give the alarm when numbers started to drop. As opposed to other methods used throughout the Atlantic and Pacific that include industrial nets and lines trapping enormous quantities of tuna of all ages and all sorts of marine life along with them. On some occasions in other countries, even explosives are used to speed up the process, killing everything around. The following video will help understand how the Almadraba actually works.

The Red Tuna of Almadraba is caught when it returns from northern Europe, after spending the winter off the freezing coasts of countries like Norway and Iceland, on the arrival of the Spring and Summer, between May and June, it sets off to the Mediterranean to reproduce in the warmer and less turbulent waters. Like all migratory animals, the Red Tuna builds up its energy reserves and fattens up as much as possible before setting out on that immense Odyssey of thousands and thousands of miles. When it appears on the Andalusian coast its meat has obtained an optimum level of fat and it is at this point when the meat is most succulent.

The Red Tuna of Almadraba can be caught ‘on the way in’ or ‘on the way out’, depending on when it passes through the Strait of Gibraltar. The return journey to northern Europe is in the months of September and October but the ‘first leg’ of the trip delivers the best quality fish and is usually dedicated in its entirety to ‘fresh’ consumption as the tuna on the way back carry less fat and the meat is dryer. Most of this ‘first catch’ is sold to Japan where they queue up to buy the Red Tuna of Almadraba. In the central market of Tsukiji (Tokyo) this tuna goes on sale to the public at well over 90 Euros a kilo and on occasion much much more. Here in Spain this year it is exported from the fishing market at around 20 Euros a kilo. A very pricey fillet by the time it reaches the consumer.

The importance of this fish and the techniques used to catch it are little known in Spain but there is a growing awareness of its value in the municipalities where you can find an Almadraba such as Conil, Barbate, Tarija and Zahara de Los Atunes where they are already boosting its gastronomic and touristic appeal.

Once the Red Tuna have been captured they are taken away to be cut up and filleted. This in itself is another art form that has been passed down over the generations and is called “El Ronqueo” because of the noise the knife makes when separating the different parts of the Bluefin. It is a hoarse grunting sound almost like the grunt of a pig caused by the knife running along the spines as they slice through the meat. It is quite impressive how they cut up a fresh Tuna in such a short time taking advantage of virtually every part of the fish and leaving just the bones, separating all the different cuts manually. Even the Japanese who are masters with their knives come to Cadiz to see the Masters of the Ronqueo and even pay more if certain reputable people have cut up the fish. It is quite a spectacle but certainly not for sensitive audiences. So who would have thought that one of the most sought after fish in Japan is actually captured in Spain?