In the Spanish language, a wide range of objects and ideas are defined by a nationality, from the so-called Russian salad (ensaladilla rusa) to the English wrench (llave inglesa), and expressions such as “voting like a Bulgarian” (votar a aprobación a la búlgara), which refers to decisions that receive unanimous approval, typically out of fear.

But what does the adjective “Spanish” mean in other languages? When, and for what reason, is “Spanish” used as a descriptor?

A group of phrase-lovers points out that the word Spanish and Spain appears in many expressions in foreign languages. On the one hand, certain languages associate Spain with the strange and incomprehensible. For example, in Slovak, saying that something is “a Spanish town” (To je pre mňa španielska dedina), means it doesn’t make any sense. The same expression exists Czech (španělská vesnice).

In German there is a similar association; if something sounds strange and unreliable, then it “sounds Spanish” (das kommt mir spanisch vor). And in French, “speaking like a Spanish cow” (parler comme une vache espagnole) is to speak very bad French.

However, when we cross the Atlantic Ocean to the United States, the word carries a completely different meaning, particularly in the world of viral memes and social media jokes. Saying a person “cries in Spanish” means they are over-the-top and exaggerate their feelings of distress. And the expression “speaking in Spanish” refers to all kinds of seduction abilities, associated with the stereotype of the “Latin lover.”

A second group points out that “Spanish” often has negative connotations, with the adjective unfairly used to describe unwelcome events and problems.

The most obvious example is the so-called Spanish Flu a reference to the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed 40 million people (including Austrian painter Gustav Klimt). Although the pandemic did not break out or spread from Spain, it is described as the Spanish flu in English, Slovak (španielska chrípka), Portuguese (gripeespanhola) and German (Spanische Grippe).

The flu was given this title because of the attention it received in the Spanish media. Other international media filled their pages with news of the First World War and censored information about the effects of the disease so as to not appear weak before their enemies. But Spain, which did not participate in this war and did not have to worry about its image, faithfully reported the news on the flu and paid for it with its name.

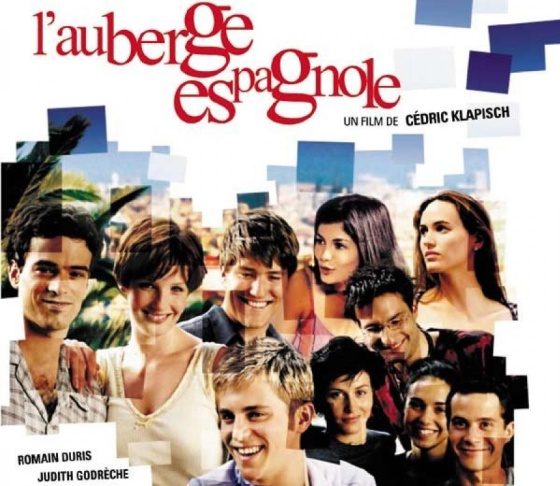

The adjective “Spanish” is also negatively used in the French phrase a “Spanish hotel” (l'auberge espagnole), which describes a place that is messy and disorganized. This was the title of a 2002 French film by Cédric Klapisch about a chaotic student apartment belonging to a group of European students in Barcelona on their Erasmus year (known as The Spanish Apartment and Pot Luck in English). Meanwhile, the French phrase to “make castles in Spain” (faire des châteaux en Espagne) is the equivalent of saying something is pie in the sky.

The adjective “Spanish” is also negatively used in the French phrase a “Spanish hotel” (l'auberge espagnole), which describes a place that is messy and disorganized. This was the title of a 2002 French film by Cédric Klapisch about a chaotic student apartment belonging to a group of European students in Barcelona on their Erasmus year (known as The Spanish Apartment and Pot Luck in English). Meanwhile, the French phrase to “make castles in Spain” (faire des châteaux en Espagne) is the equivalent of saying something is pie in the sky.

Other negative uses of the adjective are related to the Spanish Inquisition. For example, certain torture methods used during the Inquisition are described as “Spanish” in other countries. In Slovak, a “Spanish boot” (španielska čižma) refers to the iron casting that was placed on a person’s leg to crush their bones.

In English, a Spanish tickler is the name given to a metal claw that was used to rip flesh away from the bone. Another example is the English phrase “Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition,” which refers to an unexpected visit from a threatening figure. This phrase comes from a well-known episode of Monty Python.

In English, a Spanish tickler is the name given to a metal claw that was used to rip flesh away from the bone. Another example is the English phrase “Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition,” which refers to an unexpected visit from a threatening figure. This phrase comes from a well-known episode of Monty Python.

Other uses of “Spanish” in foreign languages are less negative. In ancient battles, to defend a strategic area, sharpened stones were stuck into the ground with their points facing outward. This made it hard for horses to walk and forced riders to take the road by foot. Examples of this are seen on pre-Roman walls in Celtic and Iberian areas. The invention has been called the “Spanish rider" in German (Spanischer Reiter) and in Slovak (španielsky jazdec).

Interestingly in Spain however, this defense mechanism is called “fields of stones” or the “horse of Friesland,” an allusion to Friesland, a province in the Netherlands.

When it comes to food, the word “Spanish” has a variety of meanings. Unsurprisingly, Andalusian olive oil is called Spanish oil outside of Spain (sometimes, sadly, Italian olive oil). But it also has more unexpected uses. In Germany, “Spanish” is used to describe paprika (spanischer Paprika); in Italy, ice cream with sour cherries is called spagnola (even though the berries are not eaten in Spain); in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, a meat roll stuffed with vegetables is known as a “Spanish bird” (španělský ptáček and španielsky vtáčik respectively).

Generally speaking, what is “Spanish,” according to others, tends to be associated with the outrageous, the exotic or based on common stereotypes.