The Aljafería in Zaragoza was declared a National Monument of Historical and Artistic Interest on the 4th June 1931. In 1947, however, it still remained a woeful sight in rags, according to the architect Francisco Íñiguez Almech, who for over thirty years undertook a slow and thorough recovery task. After his death in 1982, this was continued by the architects Ángel Peropadre Muniesa, Luis Franco Lahoz and Mariano Pemán Gavín. The result of all these alterations, backed by several archaeological digs, has led to the present-day appearance of the building, in which the original remains can be distinguished from the reconstructed part.

Moreover, the Regional Assembly of Aragon has its seat in one section of this collection of historical buildings. Work on the Assembly building was started in 1985 by the architects Franco and Pemán. This work is part of the aesthetic trends of contemporary architecture, and its authors have avoided including historical elements that could lead to possible mistaken interpretation. In 2001, UNESCO declared the Mudejar architecture of Aragon a World Heritage site, and praised the Aljafería palace as one of the most representative and emblematic monuments of Aragonese Mudejar Architecture.

This retains part of the primitive fortified enclosure on a quadrangular floor plan reinforced by great ultra-semicircular turrets, together with the prismatic volume of the troubadour Tower, whose lower part, which dates from the IX century, is the most ancient part of the architectonic building.

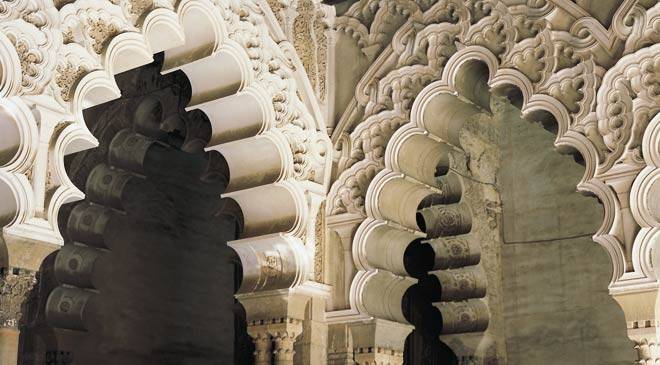

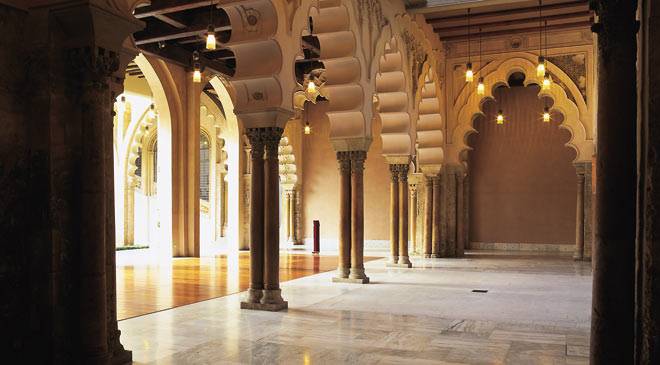

The Islamic Palace enclosure houses residential quarters in its central area which are similar to the typological model of the 'omeya' influenced Islamic palaces, just like those that had developed in the Moslem palaces in the desert (which date back to the VIII century). So, in contrast to the defensive spirit and the strength of its walls, the 'taifal' palace, which is of delicate ornamental beauty, presents a composite plan based on a great rectangular open-air courtyard with a pool on its southern side. Next come two lateral porticoes with a polycusped mixed line series of arches that acts as visual screens and at the far end some tripartite rooms, which were originally intended for ceremonial and private use. There is also a small oratory in the northern portico, with a small octagonal floor plan, in whose interior fine and lavish plaster decorations can be seen (with typical ataurique motifs) as well as some brightly coloured well contrasted pictorial fragments, which are of particular interest. All of these artistic achievements correspond to the work carried out during the second half of the XI century under the command of Abu-Ya-far Ah-mad ibn Hud al-Muqtadir, and they serve to highlight the cultural importance and the rich virtuosity of his court. Furthermore, the Aljafería is thought to be one of the greatest pinnacles of Hispano-Moslem art, and its artistic contributions were later copied at the Reales Alcazares in Seville and at the Alhambra in Granada.

The palace of the Catholic King and Queen was erected on top of the Moslem structure in around 1492, to symbolise the power and prestige of the Christian monarchs. However, the direction of the work fell to the Mudejar master, Faraig de Gali. The work blended the medieval artistic inheritance with the new Renaissance contributions. From this origin came some of the most significant examples of the so-called Reyes Catolicos style (that of the Catholic King and Queen).

The palace comprises a flight of stairs, a gallery or corridor and a collection of rooms known as The Lost Steps, which lead to the Great Throne Room. Of these, the most interesting are, on the one hand, the paving made up of small paving tiles and the tiles from Muel, and on the other, the gold and polychrome wooden ceilings among which the magnificent coffered ceiling in the Throne Room is especially remarkable.

From 1593, by order of King Phillip II, the Siennese engineer Tiburcio Spanochi drew up plans to transform the Aljafería into a modern style fort or citadel. Consequently, he provided the buildings with an outer walled enclosure with pentagonal bastions at the corners and an imposing moat surrounding it all (with slightly sloping walls and corresponding drawbridges). However, the real reason for building this fort was none other than to show royal authority in the face of the Aragonese people’s demands for their rights as well as the monarch’s wish to curb possible revolts by the people of Zaragoza. After this first military renovation, throughout the XVIII and XIX centuries, extensive alterations were made to the building to adapt it for its use a barracks. To this day the blocks built during the reign of Charles III remain, along with two of the NeoGothic turrets added during the time of Isabel II.

Lastly, it must be must be pointed out that very few Aragonese monuments have as many excellent architectonic examples such as those at the Aljafería in Zaragoza, summing up ten centuries of daily life as well as historic and artistic events in Aragon.