The ritual 'matanza' (pig slaughter) and the making of sausages and other meat products are portrayed in Roman sculpture: the Iberian Peninsula was renowned throughout the Empire for producing fine pigs and charcuterie.

The ritual 'matanza' (pig slaughter) and the making of sausages and other meat products are portrayed in Roman sculpture: the Iberian Peninsula was renowned throughout the Empire for producing fine pigs and charcuterie.

Sausages were then known as botulus (from which botulism, the name of the illness caused by inadequately preserved foodstuffs was later taken), or its diminutive botellus. Blood sausages of the black-pudding type were known as botuli, and one of the Iberian Peninsula's most characteristic sausages, the botillo, typical of the El Bierzo region (León, Castilla de León), clearly derives its name from the same source. Non-blood sausages were known as farcimina and what they contained and how they were made and cooked is explained in recipes in Apicius famous cookery book. It describes how pig intestines were stuffed with chopped meat, fat, egg, spices, offal, and so on, and how they were smoked and cured; readers are also informed that they could be eaten boiled, roasted or cooked over the fire. From this we can infer that the manufacturing method has stayed the same for at least 2,500 years and that the ingredients, too, have changed very little, even now varying from region to region and one type of charcuterie to another.

In the Middle Ages, scarcity and unhygienic conditions meant that meat was rarely eaten fresh. Despite the fact that meat was beyond the reach of most of the population except to mark the occasional feast day, the meat they did eat would have been preserved in the traditional manner, namely salted or in the form of sausages.

The most important difference between pre- and post-16th-century Spanish sausages is that many of the later ones contain a new ingredient destined to become a basic in much of Spain's cuisine: the type of paprika known as pimentón. This marvellous condiment enhanced the keeping properties of cheeses and charcuterie, added flavour and colour, and furthermore could be used to disguise certain signs that meat was going off. The tradition of adding pimentón (in its two most extreme types: sweet or hot) to many Spanish sausages is still very much alive today, and can be thanked for originating what is now perhaps Spain's most characteristic sausage - the chorizo - which was taken up all over the country, particularly in the 18th century. Today, only one region of Spain does not use pimentón in any of its traditional sausages, Catalonia's classics are seasoned with just salt and pepper.

The most important difference between pre- and post-16th-century Spanish sausages is that many of the later ones contain a new ingredient destined to become a basic in much of Spain's cuisine: the type of paprika known as pimentón. This marvellous condiment enhanced the keeping properties of cheeses and charcuterie, added flavour and colour, and furthermore could be used to disguise certain signs that meat was going off. The tradition of adding pimentón (in its two most extreme types: sweet or hot) to many Spanish sausages is still very much alive today, and can be thanked for originating what is now perhaps Spain's most characteristic sausage - the chorizo - which was taken up all over the country, particularly in the 18th century. Today, only one region of Spain does not use pimentón in any of its traditional sausages, Catalonia's classics are seasoned with just salt and pepper.

This period, too, saw the invention in Andalusia of lamb meat sausages, which are still made today. These were thought up by Jewish converts to avoid being denounced for not eating sausages while remaining within the strictures of the faith to which they still secretly adhered.

Like all meat products, sausages remained a food that only the privileged few could enjoy. Banquets held by the successive courts of modern Spain made much of the nation's varieties of sausage, though inevitably they were outshone by hams and game. Charles IV (1748-1819) was a prolific eater of chorizos, a fact celebrated by the inclusion of the figure of his supplier in a famous tapestry by Francisco Bayeu (1734-1795).

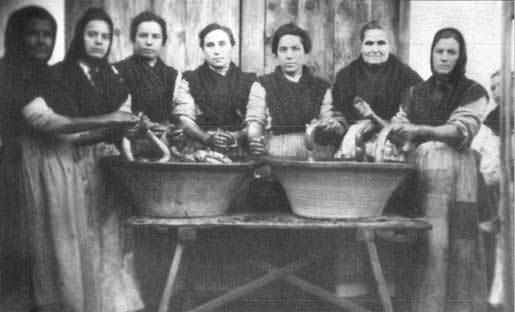

Until the closing decades of the 19th century, nearly all pork-derived products were made from the meat of the native, Ibérico, breed of pig. Pork products began to become more generally accessible in the towns and cities after specialized municipal abattoirs were opened. In the first thirty or so years of the 20th century, certain pork products and sausages started to become available to the masses. Village matanzas continued to take place in Spain right up to the end of the 20th century, surviving alongside a meat industry that grew consistently from the 1950s on, after white pigs had been introduced and become widespread.