The Cáceres Museum is housed in two historic buildings in the historic town centre of Cáceres, declared a Human Heritage Site by UNESCO.

The 'Casa de las Veletas' (Veletas Palace) houses the Archaeological and Ethnographical sections; it is a building which originates from 1600 by and was built by its owner, Don Lorenzo de Ulloa y Torres, in a site which may have been once occupied by a Muslim fortress which has now disappeared. The beautiful square patio with its eight Tuscan columns dates from this period. Nevertheless, the house was redesigned by Don Jorge de Cáceres y Quiñones, who introduced the gargoyles and the beautiful enamelled pottery ornaments on the roof, as well as the large shields on the main façade.

The Fine Arts collection can be seen in the Casa de los Caballos, which was a stable and later a dwelling until its conversion into a museum; after a recent renovation, it was opened to the public in 1992.

Although the first Board of the museum was set up in 1917, the concept of its creation arose in 1899 when a group of scholars of the history of Cáceres began to collect objects of archaeological and artistic interest and keep them in the Grammar School. In 1931 the Palacio de las Veletas was rented to house the Museum, which after an architectural refurbishment, was inaugurated on 12th February 1933.

After the later acquisition of the building, it was renovated in 1971 and the permanent exhibition was improved, a task which was repeated in 1976 in the Ethnography Section. In 1989 the Ministry of Culture transferred the management of the Museum to the Government of Extremadura, retaining for itself the ownership of the building and part of the funds.

It is the Archaeological collection which gave rise to the Museum itself, beginning its formation at the end of the 19th century. It occupies five rooms on the ground floor, and two more rooms in the basement of the same building which house the mediaeval collections, plus a third one with information about Muslim cisterns.

The chronological development of the archaeological exhibition extends from the Lower Palaeolithic to the beginnings of the Middle Ages.

The visit starts in the hall itself. This houses a big white marble sculpture which represents an androgynous genie (of a benevolent nature) coming from the Roman colony “Norba Caesarina” which gave origin to the present city of Cáceres.

Room 1 presents various lithological industries belonging to the Palaeolithic period, coming from river terraces of the province. Objects from the Neolithic period are also shown and others excavated from various megalithic tombs.

Room 2 provides a global vision of the most representative elements from the Bronze and Copper Ages, the collection of standing blocks as well as objects from the first Iron Age.

In room 3 we enter fully into the world of pre-Roman settlers. Amongst its most representative productions are the boars.

Rooms 4 and 5 are dedicated to Rome and occupy the most extensive space showing various aspects related to urban development, economy, religion and the funereal world.

The basement of the Casa de las Veletas houses the medieval collections, plus a collection of Roman epigraphy.

In room 6 objects and decorative architectural elements can be found related to funeral and liturgical spaces of the Late Roman, early Christian and Visigothic Ages.

The rooms 7 and 8 show a representative part of the important collection of Roman inscriptions reunited throughout the province, with inscriptions of three types: funerary, votive and honorary.

The epigraphic collection of the Museum, with about 150 copies, is among the most important in Spain and gives us a wealth of information on aspects such as social class, religious rites, geographical origins, etc.

Here you can visit the Islamic cistern - water deposit, dated between the 10th and 12th centuries, which was located in the basement and is the largest water deposit created in Spain under Arab rule, heir to the grand byzantine reservoirs of Constantinople. It is 14 metres long and 10 metre wide.

Situated on the first floor of the Casa de las Veletas, the Ethnography Section explains different processes and shows various objects which inform us about the models of cultural development in the province of Cáceres. Room 9 is dedicated to the production of resources, particularly agriculture, stock-breeding, hunting and grazing with interesting examples of farm implements and tools for caring for stock. Following the visit, we pass to room 10, where we can contemplate objects related to the production of resources –river fishing– and its transformation, through the production of oil, cheese and wine and the craft of carpentry.

Room 11 instructs the visitor on aspects relative to work, through activities and trades such as filigree, including the main components of a goldsmith´s workshop from Ceclavín, as well as the typical pieces of jewellery for the summer costumes of Cáceres, and mechanisms related to textile manufacture from a traditional loom to combs, carders, a winding machine or a spool. Room 12 presents a rich collection of costume, from linen undergarments to holiday and everyday clothes of Montehermoso, Serradilla, Malpartida de Plasencia, etc.

Continuing the visit in room 13, we reach a collection of items of domestic use shown together with other large objects, such as the bench and stocks for prisoners from Guijo de Granadilla, the still from Guadalupe or the mule cart from Zorita. In the showcases can be seen pottery from Talavera, Puente del Arzobispo or Manises and also examples from Extremadura, as well as objects made of horn, bone and wood. Room 14 is dedicated to beliefs and musical expression.

The Fine Arts Section consists of two rooms in which different artistic collections are placed. In room 15 the most outstanding items from the collection of Contemporary art are shown, which began with the creation of the Cáceres Prize for Painting and Sculpture in the seventies and eighties, and the works it acquired at the time and which the Junta de Extremadura continues to acquire. Exhibits representative of Contemporary Spanish Art of the 20th century can be seen, with works by artists belonging to the most representative artistic movements such as “El Paso”, with Saura, Millares or Canogar, or the Grupo Crónica. Near them are creations by key artists such as Picasso, Miró, Clavé, Genovés, Guinovart, Guerrero, Lucio Muñoz, Barjola and Tàpies. The sculpture of the 20th century is represented by Alberto, Chirino, Palazuelo and Oteiza, among others.

The collection can be described as the most important in the region relating to this period in Extremadura and, no doubt, one of the most representative of the Spanish avant‑garde, with the presence of the best known artists.

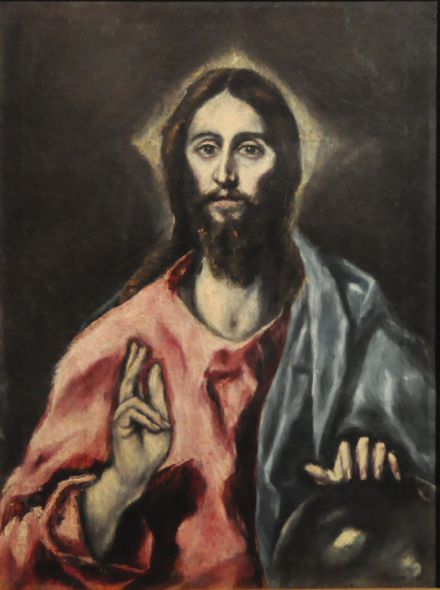

In room 17 examples of Medieval and Modern art are installed. They include sculpture (in wood, ivory and alabaster), goldwork and painting. The key piece of this room is the picture of Jesus the Saviour by El Greco, which comes from the Convent of Agustinas Recoletas del Cristo de la Victoria, of Serradilla.

The museum is very much worth a visit and not particularly well known, so if you happen to be in the area pay it a visit. It is free for all EU citizens.