Tenerife's most visible landmark, Mt Teide, has been a point of reference for those who sailed between the Straight and the Atlantic coast since antiquity and also a reference for Holywood as it has served as a backdrop for many films and was the stage for “1 Million Years B.C” which immortalised the late Raquel Welch.

With an altitude of 3,718 metres above sea level, Mt. Teide is the highest mountain in Spain and in all of the Atlantic archipelagos. The steep slopes of the mountain reach this altitude in a mere thirteen kilometres from the coastline. This is a strato-volcano-type edifice sitting on an ancient and gigantic crater-shaped depression made up of two semi-craters (calderas) separated by the "Roques de Garcia". Mt. Teide is crowned by the Pilon de Azucar (Sugar Loaf), which is still residually active in the form of fumaroles of steam and sulphur at 86º C

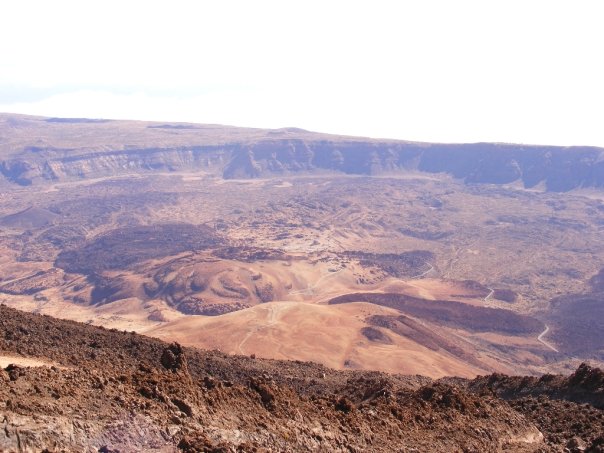

The Crater (caldera), known as Las Cañadas, takes its name from the most typical feature of the park, the Cañada, a sedimentary plain that is normally situated at the foot of the walls or amphitheatre of the caldera. This entire spectacular geological landscape is derived from a grand volcanic structure, called the Cañadas Edifice, which originally encompassed the central sector of Tenerife. This edifice, with its enormously complex structure, grew in height over the millennia due to the accumulation of large quantities of lava flows and layers of pyroclasts, spewed out in many successive eruptions that occurred over a period of 3.5 million years, with alternating periods of construction and destruction.

The Las Cañadas Circus still arouses controversy among geologists as there are several hypotheses about how it was formed, such as an explosion, erosion, collapse and major landslips. The most widely accepted theory until the early nineties was the hypothesis of a collapse as the fundamental cause. Research of the island sub-soil, however, and studies of the sea bed and its relief, in the final years of the 20th century, have confirmed the hypothesis maintained by Tenerife geologist and geographer Telesforo Bravo since 1962, against the general opinion of the scientific community of the time; i.e. that both Las Cañadas del Teide and the Orotava and Güimar Valleys are depressions formed by massive gravitational landslides, of over 100 cubic Km of earth.

The last recorded eruption that took place within the current boundaries of the national park occurred on the slopes of Pico Viejo, or Chahorra, in 1798, over a period of three months. This was the longest of all the eruptions that have occurred in recorded history in Tenerife: the lava spewed out of a fissure almost one kilometre long covered an area of almost 5 square kilometres and almost spilled over the wall of Las Cañadas through Boca de Tauce, one of the lowest points of the amphitheatre.

The environment is completed by the endorheic plains or flats of sedimentary material all along the base of the wall. These enclaves were called "cañadas" (passes or trails in Spanish) because they were important routes for guiding livestock through a genuine sea of lava, and this name lives on today. This explains the origin of the entire mountain peak area of the island, known in general terms as "Las Cañadas del Teide", or the Mt. Teide Passes. This vast natural cut or amphitheatre reveals the internal structure of the old volcanic edifice (Cañadas Edifice), forged by layers being laid down, one on top of another, recording the history of the eruptions of over a period of 3 million years. Las Cañadas circus is one of the largest calderas in the world. It is elliptical in shape, 16 km across at the widest point, 10 km across at the narrowest and with a perimeter of 45 km, of which, the part that is currently visible covers some 23 km, as the north wall was buried by later eruptions, which have led to the formation of Mt. Teide. The lava from different eruptions has filled in extensive areas of the former caldera with volcanic material of all kinds, sculpting a spectacular landscape of apparent chaos. So, more rounded volcanoes can be seen with yellowish and whitish tones due to the accumulation of pumice stone, like Montaña Blanca, or cones of ash and cinder, ranging in colour from reddish to black, due to the varying processes of oxidation over time, almost perfectly shaped structures like Montaña Mostaza. The lava flows sometimes form slag fields known as "malpaises" or "badlands", others fall down the slopes or run over older volcanoes, forming tongues, and others break up into enormous blocks, such as the "Valle de las Piedras Arrancadas" (Valley of the Broken Stones), near Montaña Rajada, where obsidian, shiny black volcanic glass, abounds.

Obsidian was the raw material for the stone industry of the Guanches, who used it to make cutting tools that they called "tabonas".

To climb to the summit of the Teide, at a height of 3,718 metres, is a unique experience. The fact that part of the route can be done by cable car allows anyone, no matter what there physical condition is to make the ascent. The more adventurous can ascend on foot by the path that leaves from the area of Montaña Blanca, next to the road. This is the only route allowed and is quite demanding which takes almost six hours of walking.

The cable car service, which runs every day if the weather conditions allow, reaches the area known as the Rambleta, at a height of 3,555 metres. The rest of the ascent, a little over 200 metres, must be made on foot. Access to the peak (along the Telesfero Bravo path) is restricted and you need to apply for a permit to reach the summit whether you are on foot or going by cable car.

Ver mapa más grande