Salamanca - Home to Spain's Oldest University

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

Over two thousand years is sufficient time to amass all kinds of events, large and small, happy and dramatic, glorious or difficult. The Celtic tribes of the Vettones and Vacceos, Hannibal and the Romans; the re-founding of the city by Alfonso VI, following the sacking of Toledo by the Moors, the wars between the factions, the ruling of the nobility in the 14th and 15th centuries, the War of the Commons, the splendour of the XVI century when Salamanca was the epicentre of learning and worldly knowledge, the crisis of the Baroque period, the Peninsular War, and the isolation of the 19th and a good part of the 20th century, have moulded both the physical and the spiritual aspects of the city’s structure, identity and culture. UNESCO designated it a World Heritage City in 1988 and it became European Culture Capital in 2002.

With the Plaza Mayor, the Clerecía: the Jesuit seminary, the University and the New Cathedral, Salamanca is one of the essential centres of a dynasty of architects, decorators and sculptors from Catalonia, the Churriguera. This Churrigueresque style also exerted considerable influence in the 18th century in the countries of Latin America. The Roman bridge that spans the River Tormes south-west of the city is one of the numerous witnesses, that still stands today, to the 2,000-year history of ancient 'Salmantica'. However, only the arches on the city-side of the bridge are original, the rest date from the rebuilding of the bridge in the 18th century. This bridge is part of the renowned Ruta de la Plata, a route that was of major economic and strategic importance following the Roman occupation. Salamanca's monuments have an exemplary value: the Old Cathedral, the Salina Palace and above all the Plaza Mayor, the most sumptuous of the Baroque squares in Spain.

However, the city owes its most essential features to the University. The remarkable group of buildings in the Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque styles which, from the 15th to the 18th centuries, grew up around the institution that proclaimed itself 'Mother of Virtues, of Sciences and of the Arts' makes Salamanca, like Oxford and Cambridge, an exceptional example of an old university town in the Christian world. Although officially founded later than those of Bologna, Paris, Cambridge and Oxford, the University of Salamanca had already established itself in 1250 as one of the best in Europe even though it had been founded as a place of study in 1218 by order of King León Alfonso IX.

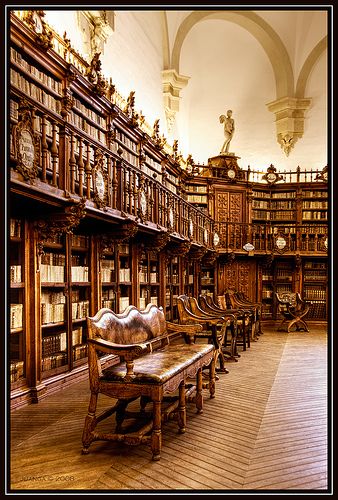

It followed the Bologna model, namely it gave preference to the study of Civil and Canon Law over theology and philosophy which were favoured at the University of Paris. During its period of greatest splendour, the 15th and 16th centuries, it was the head of the European Universities. It is currently the oldest university in Spain. One of the main features is the Fray Luis de León lecture hall, the reliefs along the stairwell of the cloister, and the Library, founded in 1254 by Alfonso X “the Wise”, with a collection that contains a large number of priceless manuscripts and pre-1500 publications. Amongst these priceless treasures is a copy of the Tohá and the so-called “libros redondos” that Torres Villaroel bought in Paris and which are in fact globes, but he gave them this name so that the librarian at that time would agree to pay for them. The Escuelas Menores courtyard leads to the "Cielo de Salamanca" (heaven of Salamanca). It represents an astrology programme that was undoubtedly involved with the teaching of astronomy and astrology at the University. In keeping with student tradition, if you want to breeze through your exams, you must first see the frog on the University facade. On almost all of the university buildings, you will find one of the famous "vítores" wall paintings. These were originally painted using bulls blood and symbolise the victory of the recently graduated Doctorate students over their books.

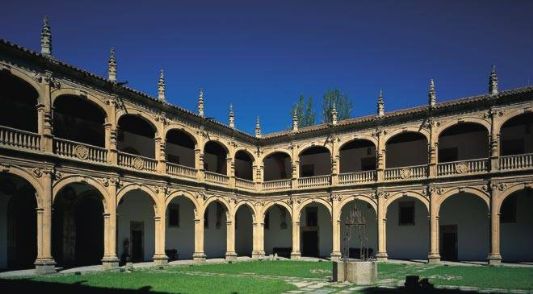

The most beautiful example of the Renaissance colleges in Salamanca is the Colegio de los Irlandeses built between 1527-1578 to house Irish students. Others ancient buildings are the Colegio de Huérfanos; the Colegio San Pelayo; the Colegio Santa Catalina; the Colegio San Ildefonso. The superb Baroque colleges of the 18th century are Colegio de la Ordén Militar de Calatrava, Colegio de San Ambrosio, and Colegio de l'Universitad Pontificia, with its marvellous patio, 'Salon des Actos' and monumental stairway. The more austere Colegio de Anaya was one of the last monuments of this institution to be built in a style inherited from the Middle Ages, along with the Colegio de Santa Maria de Los Angeles, founded in 1780; the latter incorporates the late Gothic style facade of the earlier Colegio de San Millán.

The Royal College of the Jesuit Order was built in part by Gómez de Mora in 1611. The missionaries that were trained went on to spread the Catholic Faith around the world. Nevertheless, the herculean construction task lasted another 150 years before it was completed at which time, in 1767, the Jesuit Order was expelled from Spain by Carlos III. The building was subsequently split into four, was abandoned and then suffered the scorn of war, ecclesiastical confiscation and finally ruin. It was in 1946 that it was reformed and was used to house the Pontifical University. Both the college and the private areas of the nuns have an upper gallery allowing them to go for strolls and enjoy the sun in the winter months, as the convent has neither allotment nor garden.

The Casa de las Conchas (House of Shells) is one of the most popular palaces of Salamanca and one of the best examples of Spanish Gothic civil architecture. It was commissioned in the late 15th and early 16th century by Don Rodrigo Arias Maldonado, a relative of the Catholic Kings and Knight of the Order of Saint James. The shells are the main ornaments of the building’s facade.

One of the aspects that generates a great deal of interest is why he chose the shells as the ornamental detail. Some believe that it was a show of pride by Maldonado for belonging to the order of Saint James. Others, undoubtedly more romantic, believe that the repetition of the shell, in heraldic terms, was an expression of love felt by Lord Rodrigo for his wife, Lady María.

Salamanca's Plaza Mayor is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful squares in Spain and in the world and one of the best examples of Baroque architecture in the Peninsula. Since work was completed on it between 1729 and 1755, this typical Castilian square, has been the meeting point for the people of Salamanca - who see it as their living room – and foreigners alike. Awarded the status of National Monument in 1935, in the technical and artistic accreditation it states that it is "the most decorated, proportionate and harmonious of all the squares of its period in Spain". It has 88 arches and a number of medallion reliefs. Currently, as in the past, the square is still the venue for the city’s major religious and civil celebrations: bull-fighting, processions and in the past, even executions. That is why some owners of the properties are able to rent out their balconies for certain events at a considerably high price.

.jpg)

Each year on 15 August, above the belfry of the City Hall they place a flagpole, on top of which stands the figure of a bull with the Spanish flag. The figure, which is given the name of "Mariseca", is placed there to announce the approach of the Salamanca festivals, and it is not removed until they are over.

The silhouette of the Cathedrals towers over the Salamanca skyline and its inside reflects the life and history of the city and the city’s residents. Together, standing side by side, they go to form a wonderful historical and artistic complex: the Old Cathedral and the New Cathedral. The new one, a fusion of Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque architecture. The Old one is Romanesque. To access the Old Cathedral, you must first go through the new one. As you walk through the door, you are taken back in time, this Romanesque church is home to an ancient, medieval spirit. Architecturally speaking, a defensive building, linked to the period of resettlement (work on its construction began in around 1509, of a people at war where the heroes of the time were the so-called warrior saints (Raimundo de Borgoña or Bishop Jeronimo). The San Martín Chapel is also known as the Aceite (oil) Chapel because it was used to store the earthenware jars of oil that were used to fuel the lamps in the Cathedral. The thickness of its wall meant that during the Spanish Civil War, it was used as an air-raid shelter, and even General Franco is reputed to have sheltered there.

Towards the end of the 15th century, the population of Salamanca underwent huge growth, thanks to the popularity and renown of the University. The Old Cathedral was now too small, and the mostly Gothic aesthetic and ideology of its interior made it a rather archaic venue and it was simply not very practical. So in 1513 work began on the construction of the New Cathedral, one of the last Gothic cathedrals to be built in Spain, and it was completed some two centuries later in 1733. Different architectural styles seem to randomly appear in its construction. The New Cathedral epitomises urban development. Its opulence reflects its triumph over its ideological rivals and of its parishioners. It is both the largest and the tallest building in the city. In 1755, the famous Lisbon earthquake seriously damaged the bell tower. The bell mechanism was damaged so the bell-ringer had to climb up to the bells to ring them. This tradition continues to this day and each 31 October, someone wearing a traditional Salamanca outfit climbs the tower and plays a Charrada a traditional Salamanca tune.

Considered by many to be the Spanish Renaissance city par excellence, it makes for a unique setting, both for its architectural and urban beauty which has survived the test of time and for its important role regarding humanistic thinking and the thirst for knowledge so prevalent in this historic period. Sunrise and sunset are magical moments. The light manages to transform both the interior of the buildings and their exterior, a singular light that bathes the gilt-coloured façades that reflect the famous people who once walked its streets, and whose presence can still be felt.

Best time of year to visit: All year but also at Easter.

0

Like

Published at 8:32 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 8:32 PM Comments (0)

Altamira - A Prehistoric Masterpiece

Thursday, September 17, 2020

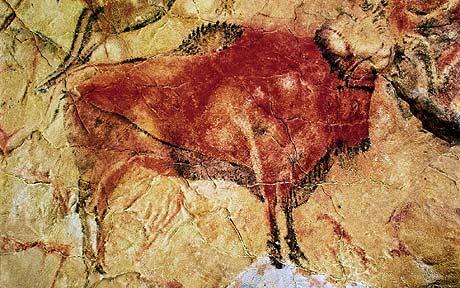

Altamira, the subject of a film at present with Antonio Banderas, was the first cave in which prehistoric cave paintings were discovered. When the discovery was first made public in 1880, it led to a bitter public controversy between experts which continued into the early 20th century, since many did not believe prehistoric man had the intellectual capacity to produce any kind of artistic expression. The acknowledgment of the authenticity of the paintings, which finally came in 1902, changed the perception of prehistoric human beings.

The cave represents the apogee of Paleolithic cave art that developed across Europe, from the Urals to the Iberian Peninusula, from 35,000 to 11,000 BC. Because of their deep galleries, isolated from external climatic influences, these caves are particularly well preserved. The caves are inscribed as masterpieces of creative genius and as the humanity’s earliest accomplished art. They are also inscribed as exceptional testimonies to a cultural tradition and as outstanding illustrations of a significant stage in human history.

UNESCO granted the World Heritage designation to these and another 17 caves in northern Spain containing Palaeolithic Cave Art. The Altamira cave has an irregular shape and is some 270 metres in length. It has an entrance hall, main gallery and side hall, and contains some of the world’s best examples of prehistoric rock art. The drawings are some 14,000 years old and show bison, deer, boar, horses… They are painted using natural, red-coloured ochre and outlined in black.

To ensure their conservation, the cave structure and paintings have been painstakingly reproduced, using the same painting techniques from the time, in the Altamira Museum’s Neo-cave. Visitors can marvel at the details of the great ceiling with its polychromed bison, and visit the painters’ workshop, where they can hear an explanation of the techniques used to create this masterpiece of rock art.

Admission charges:

General public: 3 €

Concessions: 1.50 €

Annual pass: 25 €

Free admission

Saturdays from 14:00 and all day Sunday.

18 April, World Heritage Day.

18 May, International Museum Day.

12 October, Spanish National Day.

6 December, Spanish Constitution Day.

1

Like

Published at 5:21 PM Comments (2)

1

Like

Published at 5:21 PM Comments (2)

The Valley of Salt - Northern Spain

Thursday, September 3, 2020

Salt has always been associated with the sea or on some occasions, salt mountains and even mines, but in Northern Spain, in the Basque country near the town of Álava, there is a rather unusual saltern where nature does practically all the work and has been for millenniums. This privileged location is called the Salt Valley of Añana.

The first thing you might ask yourself when you see this marvel is how and why is salt produced here and not someplace else? Especially when there is no mine visible. The answer is a geological phenomenon known as a Diapir. Roughly speaking, the area that makes up the valley was covered by a big ocean more than 200 million years ago that eventually dried up, leaving a layer of salt several kilometres thick. With time, this layer was covered by new stratum that hid it from sight forever. Because of the different densities between layers (similar to what happens when we mix water with oil), in some very specific points of the valley, the salt emerged to the surface. And those are the places where we can find the underground salt deposits. But how do you extract it? The answer is simple: either by mining which is hard work and expensive or taking advantage of the saltwater (brine) springs that are created after freshwater has filtered through the layers of solid salt diluting it and bring it to the surface, and enabling a 200 million-year-old mineral to reach your kitchen table. The salt works of Añana belong to the large group of neighbours in fact almost the entire population of the village owns shares in the salt plant as they are fortunate enough to have several springs that provide around 260.000 litres of brine daily with a concentration near to saturation point. The first thing you might ask yourself when you see this marvel is how and why is salt produced here and not someplace else? Especially when there is no mine visible. The answer is a geological phenomenon known as a Diapir. Roughly speaking, the area that makes up the valley was covered by a big ocean more than 200 million years ago that eventually dried up, leaving a layer of salt several kilometres thick. With time, this layer was covered by new stratum that hid it from sight forever. Because of the different densities between layers (similar to what happens when we mix water with oil), in some very specific points of the valley, the salt emerged to the surface. And those are the places where we can find the underground salt deposits. But how do you extract it? The answer is simple: either by mining which is hard work and expensive or taking advantage of the saltwater (brine) springs that are created after freshwater has filtered through the layers of solid salt diluting it and bring it to the surface, and enabling a 200 million-year-old mineral to reach your kitchen table. The salt works of Añana belong to the large group of neighbours in fact almost the entire population of the village owns shares in the salt plant as they are fortunate enough to have several springs that provide around 260.000 litres of brine daily with a concentration near to saturation point.

Looking at it today, it's almost inconceivable that something so abundant and low cost would have had such historical importance. However, it has to be taken into consideration that salt was, and is, essential in a lot of industrial processes and also in human and animal diet. It was even more important before the development of industrial cooling since it was one of the most effective methods of preserving food. As a matter of fact, salt was the cause of war and forced peace, the cause of death and crownings, of richness and poorness, the creation and destruction of towns and cities, and of course, greed. This is very evident in the history of Añana... The first traces of settlements near the salt springs date back 5,000 years. Since then their inhabitants adapted the area to their interests and left their mark. In the Iron Age, they left the bottom of the slopes and built their houses on easily defendable elevated sites and in Roman times, the settlement system suffered a big change. Probably due to the importance of the salt of Añana, just a few kilometres from the springs, near the modern-day town of Espejo, emerged a city called Salionca. Its economic development attracted the surrounding population to live in this thriving city. Around the fifth century, Salionca was destroyed after suffering a major fire and the city was abandoned and some of its inhabitants went to live and work in the salt valley.

The springs bring the brine to the surface level in a natural and continuous way, which allows its use without any need for drilling or pumping. It is entirely ecological. There are a number of them in the Salt Valley and its surroundings, but only four of them (Santa Engracia, La Hontana, El Pico and Fuentearriba) are usable because their flow is permanent (about 3 litres per second) and salinity is near saturation point (210 grams per litre).

The saltwater is transported and distributed continuously and by using gravity through a complex network of canals called 'rollos'. Although originally many of them were simple trenches dug in the ground, they eventually were replaced by hollowed-out pine logs. The main distribution system, with more than three kilometres in total length - starts at the fountain of Santa Engracia in a single channel which is divided within a distribution tank called a 'Partidero': on the eastern slope of the valley, the Royo de Suso flows down and on the west slope the Quintana.

Deposits are also imperative for the salt farm. Currently, there are 848 wells for storage and way this water is distributed to the different threshing pits have always been an issue of dispute, as they are each privately owned and maintained by their respective owners. Thus there is a need for a complex distribution rulebook for the use of the brine, known as the Master Book. This ultimately keeps the peace between numerous owners.

The production of salt in Añana is based on the evaporation of water from the brine by natural means. To do so, saltwater is poured on horizontal surfaces called 'balsas' (rafts) or threshing pits whose surface varies between twelve and twenty square meters. The groups of threshing pits worked by the same owner are called farms. They are adapted to the complex topography of the site, both in form and height, resulting in complicated shapes that cover most of the Salt Valley territory. The point of maximum splendour was in the middle of the twentieth century when in the valley there were 5648 threshing pits in operation.

The buildings destined to store the salt in Añana can be divided into two types: private and public. The former was originally owned by salt workers. Such structures are mainly located under the threshing pits, taking advantage of existing holes between the walls of the terraces and the evaporation platforms. This building technique greatly facilitates the filling, because the salt is simply discharged by small holes in the surface of the threshing pits called 'bouquets' (sluices). The main function of these buildings is to hold the salt until transported to public warehouses located outside the valley. Añana had four of these buildings, which were built and controlled by the State during the monopoly of salt. They became known as El Grande, El Torco, Santa Ana and El Almacenillo del Campo. The whole production was kept there at the end of the season. In total, they could store about 110,113 “fanegas” of salt (approximately 5,681,830 kg). Now it is all in hands of the local community and although they could be extracting salt most of the year, they limit it to a few months a year when the temperatures are high enough to achieve fast evaporation, thus reducing the costs of labour per kg produced.

If you happen to be in the area it is certainly worth a visit, on-site there are tourist guides and trips around the valley and a museum with a shop where you can choose from a vast variety of different salts varying from “Flor de Sal” the most valuable; known as white gold and seasoned salts amongst others. This is one lucky village that has a permanent source of income no matter what the economic climate is, in fact, the only thing that would affect its production would be the lack of sunshine and in Spain that is not very likely.

0

Like

Published at 8:42 PM Comments (2)

0

Like

Published at 8:42 PM Comments (2)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|