Discover the Ribeira Sacra

Thursday, February 16, 2023

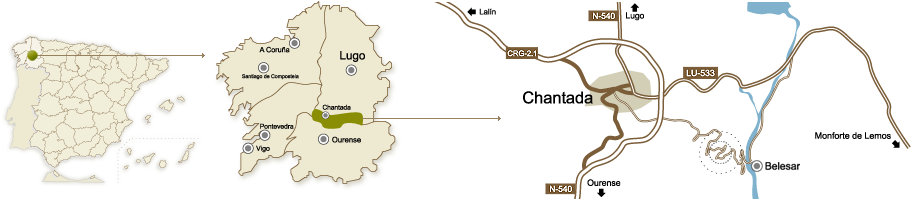

The Ribeira Sacra is an area in inland Galicia that is home to spectacular natural features such as the canyon of the Sil River, this region’s most emblematic landmark and a wide array of valuable artistic heritage. Referred to as the land of monasteries, it is graced with over a dozen demonstrating the huge importance of this region during the Middle Ages. It is a genuine journey back in time. However in recent history, the Ribeira Sacra region had lost a significant amount of importance but over the past few years, its international success in wine producing and rural tourism is putting it back on the map.

The Sil River which identifies the region, forms a natural boundary between the provinces of Ourense and Lugo, in the heart of Galicia in northern Spain. You'll be breath-taken by its rugged landscapes, dominated by vineyards, mountains and ravines. The Ribeira Sacra region, follows almost 200km of river, a region which is peppered with historical architecture such as churches and shrines, mostly in the Romanesque style, as well as palaces and monasteries. Home to Spain's oldest Christian parishes, the Ribeira Sacra was the starting point for Christianity on the Iberian Peninsula.

1,500 years ago, congregations of monks and hermits settled here, and for centuries devoted themselves to meditation and reflection. This peace and harmony live on to this very day in the region's villages and medieval monasteries. Unfortunately, some are now abandoned but are still well worth visiting as their walls have been witnesses to the passing of time and the damp, moss and vegetation impart an uncanny air of mystery.

They are reached by means of forest tracks and country roads running through lush green forests. One of the most important is the monastery San Esteban de Ribas de Sil, located to the north of Nogueira de Ramuín. Besides being the largest in the Ribeira Sacra, it is now a luxurious Parador Hotel, a place I would very much like to spend an evening or two.

In the same village, you'll find the monastery of Santa Cristina, where you can stroll around its cloisters and surroundings and soak up the magical atmosphere. Very close by are some of the region's most famous viewing points: the Balcones de Madrid. From this natural terrace, you can see the immensity of the Sil River canyon, with gorges up to 500 metres deep. The views are spectacular. Once here you can explore this section of the river (40 navigable kilometres) by catamaran. There are routes of differing durations. The longest, which takes approximately three hours and can be done at any time of year, runs from Abeleda to Os Chancís, 24 kilometres downstream. There are also shorter routes, such as the one departing from the San Esteban pier to Abeleda.

The Ribeira Sacra offers a whole list of historical sites to visit, such as Montederramo and the Santa María monastery, now a school. One can also visit Tarreirigo, where you'll find San Pedro de Rocas, a chapel carved straight out of the rock, and considered the oldest monastery in Galicia. Another option is to go to Ferreira, home to the convent of Las Madres Bernardas, the only convent in Galicia occupied by nuns since its foundation until the present day. Or else you could even opt to experience all the charm of Monforte de Lemos, an interesting medieval town.

In addition to the landscape and its historical attractions, one of the strengths of the Ribeira Sacra is its cuisine. In the Ribeira Sacra, we can find a wide range of quality local products and delicacies, many of them with a protected origin, which can be tasted in restaurants and farmhouses throughout the area. The speciality of the Ribeira Sacra is its high-quality pork. The historical importance of pig slaughter in the region continues to this day and offers a fantastic choice of pork products throughout the year: cured sausages, cured hams, chorizos, androllas and the list goes on. In addition to pork, the Ribeira Sacra is also well known for veal, goat, lamb, small game and large game (in season) as its land is extremely fertile. Cherries, chestnuts and honey are also highly valued products in the region but what has been crossing borders and carrying the flag for this region is its wine. The cultivation of wine in this region dates back over 2,000 years when it was introduced by the Romans and then continued to be a key element for monastic communities throughout the Ribeira Sacra. It was really the monks who cultivated and perfected the techniques in the region and are responsible for modelling the extraordinary landscape with terraces we can see today all along the river.

Today wine production is the major driver of economic development within the Ribeira Sacra. The creation of the Denomination of Origin and the Regulatory Council in 1997 was a powerful stimulus to increase not only the quantity but also the quality of the wine produced and I have to say today they are making some fantastic wines throughout the 1,550 hectares dedicated to vineyards in the region. In 2005 they reached 99 winemakers. Undoubtedly the best red wines produced in the Galicia are from the Ribeira Sacra. The reds of the Ribeira Sacra are best served at room temperature and are perfect with all kinds of meats but especially game.

For wine lovers who just can’t resist visiting wineries, tasting wines and the opportunity to buy “in situ”, the Ribeira Sacra is a wonderful route to take. Every day the number of wineries that can be visited increases and are included in Wine Tourism Programmes and shortly the future Museum of Wine in Monforte de Lemos will be opening its door. One of the finest wines I have tried from the region is “Via Romana”, a great wine, either red or white, I’m sure you’ll just love them.

3

Like

Published at 6:28 PM Comments (2)

3

Like

Published at 6:28 PM Comments (2)

The Olive Tree

Friday, February 10, 2023

The origin of the olive tree is lost in time, coinciding and mingling with the expansion of the Mediterranean civilisations which for centuries governed the destiny of mankind and left their imprint on Western culture.

Olive leaf fossils have been found in Pliocene deposits at Mongardino in Italy. Fossilised remains have been discovered in strata from the Upper Paleolithic at the Relilai snail hatchery in North Africa, and pieces of wild olive trees and stones have been uncovered in excavations of the Chalcolithic period and the Bronze Age in Spain. The existence of the olive tree therefore dates back to the twelfth millennium BC.

The wild olive tree originated in Asia Minor where it is extremely abundant and grows in thick forests. It appears to have spread from Syria to Greece via Anatolia (De Candolle, 1883) although other hypotheses point to lower Egypt, Nubia, Ethiopia, the Atlas Mountains or certain areas of Europe as its source area. Caruso for that reason believed it to be indigenous to the entire Mediterranean Basin and considers Asia Minor to have been the birthplace of the cultivated olive some six millennia ago. The Assyrians and Babylonians were the only ancient civilisations in the area who were not familiar with the olive tree.

Taking the area that extends from the southern Caucasus to the Iranian plateau and the Mediterranean coasts of Syria and Palestine (Acerbo) to be the original home of the olive tree, its cultivation developed considerably in these last two regions, spreading from there to the island of Cyprus and on towards Anatolia or from the island of Crete towards Egypt.

In the 16th century BC the Phoenicians started disseminating the olive throughout the Greek isles, later introducing it to the Greek mainland between the 14th and 12th centuries BC where its cultivation increased and gained great importance in the 4th century BC when Solon issued decrees regulating olive planting.

From the 6th century BC onwards, the olive spread throughout the Mediterranean countries reaching Tripoli, Tunis and the island of Sicily. From there, it moved to southern Italy. Presto, however, maintained that the olive tree in Italy dates back to three centuries before the fall of Troy (1200 BC). Another Roman annalist (Penestrello) defends the traditional view that the first olive tree was brought to Italy during the reign of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus the Elder (616 - 578 BC), possibly from Tripoli or Gabes (Tunisia). Cultivation moved upwards from south to north, from Calabria to Liguria. When the Romans arrived in North Africa, the Berbers knew how to graft wild olives and had really developed its cultivation throughout the territories they occupied.

The Romans continued the expansion of the olive tree to the countries bordering the Mediterranean, using it as a peaceful weapon in their conquests to settle the people. It was introduced in Marseille around 600 BC and spread from there to the whole of Gaul. The olive tree made its appearance in Sardinia in Roman times, while in Corsica it is said to have been brought by the Genoese after the fall of the Roman Empire.

Olive growing was introduced into Spain during the maritime domination of the Phoenicians (1050 BC) but did not develop to a noteworthy extent until the arrival of Scipio (212 BC) and Roman rule (45 BC). After the third Punic War, olives occupied a large stretch of the Baetica valley and spread towards the central and Mediterranean coastal areas of the Iberian Penisula including Portugal. The Arabs brought their varieties with them to the south of Spain and influenced the spread of cultivation so much that the Spanish words for olive (aceituna), oil (aceite), and wild olive tree (acebuche) and the Portuguese words for olive (azeitona) and for olive oil (azeite), have Arabic roots.

With the discovery of America (1492) olive farming spread beyond its Mediterranean confines. The first olive trees were carried from Seville to the West Indies and later to the American Continent. By 1560 olive groves were being cultivated in Mexico, then later in Peru, California, Chile and Argentina, where one of the plants brought over during the Conquest - the old Arauco olive tree - lives to this day.

In more modern times the olive tree has continued to spread outside the Mediterranean and today is farmed in places as far removed from its origins as southern Africa, Australia, Japan and China. As Duhamel said, "the Mediterranean ends where the olive tree no longer grows", which can be capped by saying that:

"There where the sun permits, the olive tree takes root and gains ground".

0

Like

Published at 7:40 PM Comments (2)

0

Like

Published at 7:40 PM Comments (2)

Cooking 'Old Clothes'!

Thursday, February 2, 2023

One of the greatest pleasures of making a good Cocido Madrileño - Madrid stew - is being able to enjoy the leftovers. It is worth cooking a little extra in order to prepare another delicious dish. "Ropa vieja" (old clothes in Spanish) is a recipe which is just as good if not better than the original stew it is made from! This dish is a very common recipe in Madrid, Castilla-La Mancha and even in the Canary Islands.

The base for the recipe is the Cocido Madrileño or any variety of chickpea stew, even a traditional Valencian Puchero can be used. But here I will share the recipe when using a Cocido Madrileño:

Ingredients for 4 people - ROPA VIEJA

1 Onion

300g Stew leftovers (chickpeas, meat, vegetables, black pudding etc)

1 tablespoon Sweet paprika

3 tablespoons Extra virgin olive oil

2 Garlic cloves

Total time: 40m

So we start with the leftovers of the Cocido Madrileño stew, or any other traditional stew with chickpeas from your area. The main ingredient from the leftovers we are going to use is the cooked chickpeas, then of course the remains of the meat and the vegetables: cabbage, carrot and potato. Everything has to be well chopped so that there are no pieces larger than the chickpeas. We will also use a couple of ladles of the stew broth to give the final result a sweeter touch as I will explain later.

We start by poaching a finely chopped brown onion until it is golden brown, almost caramelized, so don't rush it. Then put it to one side. We continue to finely chop two cloves of garlic and add them to the pan with two tablespoons of olive oil, letting them brown over very low heat. When the garlic is golden, remove the pan from the heat and add a tablespoon of paprika, stirring it so that it mixes well with the oil and does not burn or it will go bitter.

Add the chickpeas, the vegetables and the very minced stew meat to the pan. Mix well and let all of it cook over low heat for about ten minutes, stirring so that the oil with the garlic, onion and paprika sauce permeates all the food. The flavour of the Ropa Vieja will depend mainly on what is left over from your stew, especially if there is more or less chorizo, bacon, black pudding, etc. as these ingredients add strong flavours.

The final touch will depend on your taste. Some people prefer to let the chickpeas cook until they are dry and crunchy and others prefer to add one or two ladles of stew broth at the end of the preparation process to make the "old clothes" easier to swallow! I prefer that to be honest.

This dish or recipe for making use of leftovers is designed to be eaten as a single dish because it has a great satiating effect like almost all legume recipes. You can give it a final touch by adding a splash of white wine vinegar - especially an aromatic one - something I do like to do and works really well.

Enjoy!

1

Like

Published at 8:24 PM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 8:24 PM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|