How olives actually get to your table...

Thursday, April 30, 2020

The sales of table olives have shot through the roof in Spain during the lockdown. Mainly because everyone is snacking at home and enjoying their aperitifs in their living room, on their balcony or terrace. That ice-cold beer or chilled wine with a bowl of nuts or olives can not be missed even through quarantine. However, people often think that table olives can come straight off the tree and into a jar with perhaps some seasoning, but this is not the case and far from it. The substance that renders it essentially inedible is oleuropein, a phenolic compound bitter enough to shrivel your teeth. The bitterness is a protective mechanism for olives, useful for fending off invasive microorganisms and seed-crunching mammals. In the wild, olives are dispersed by birds, who avoid the bitterness issue by swallowing them whole. Given the awfulness of the "au natural" olive, you can’t help but wonder why early humans, after the first appalling bite, didn’t shun the olive tree forever.

The olive is a drupe or stone fruit, like cherries, peaches, and plums, in which a fleshy outer covering surrounds a pit or stone, which in turn encases a seed. In the case of the olive, the outer flesh contains up to 30 per cent oil—a concentration so impressive that the English word oil comes from the ancient Greek "Elaia", which means olive. But it also has a low sugar content from 2.6-6% when compared with other drupes which have on average 12%.

Due to these characteristics, it makes it a fruit that cannot be consumed directly from the tree and it has to undergo a series of processes that differ considerably from region to region, and which also depend on the variety of olive. Some olives are, however, an exception to this rule because as they ripen they sweeten right on the tree, in most cases this is due to fermentation. One case is the Thrubolea variety in Greece, however, this is not at all common.

The oleuropein, which is distinctive to the olive, has to be removed as it has a really strong bitter taste and those who have eaten an olive straight off the tree know what I am talking about: it is not, however, pernicious to health. It just tastes terrible. Depending on local methods and customs, the fruit is generally treated in sodium or potassium hydroxide, brine or successively rinsed in aerated water, a rather complicated process.

The olive's suitability for table consumption is a function of its size, which is important for presentation. Olives between 3 and 5g are considered medium-sized, while those weighing over 5 g are large. The stone should come away easily from the flesh and a ‘flesh to stone’ ratio of 5 to 1 is considered acceptable. The higher this ratio the better the commercial value of the olives. The skin of the fruit should be fine, yet elastic and resistant to blows and to the action of alkalis and brine.

High sugar content in the flesh is an asset. The lowest acceptable level is 4%, especially in olives that undergo fermentation. For table olives, oil content should be as low as possible because in many cases it impairs the keeping properties and consistency of the processed fruit. Only in certain types of black olives is a medium to high oil content desirable.

In Spain, most of the table olives are green olives. These are obtained from olives harvested during the ripening cycle when they have reached their normal size, but prior to colour change. They are usually hand-picked when there is a slight change in hue from leaf-green to slightly yellowish green and when the flesh begins to change consistency but before it turns soft. Colour change should not have begun. Trials have been run to machine harvest table olives, but owing to the high percentage of bruised fruit they had to be immersed in a diluted alkaline solution while still in the orchard, this being said table olives are still in their majority harvested by hand. Recently harvested, the olives should be taken to the plant for processing on the same day.

Green olives are processed in two principal ways: with fermentation, which is considered the Spanish style, and without fermentation, which is considered the Picholine or American style.

In Spain the majority of olives are treated in a diluted lye solution (sodium hydroxide) to eliminate and transform the oleuropein and sugars, to form organic acids that aid in subsequent fermentation, and to increase the permeability of the fruit. The lye concentrations vary from 2% to 3.5%, depending on the ripeness of the olives, the temperature, the variety and the quality of the water. The treatment is performed in containers of varying sizes in which the solution completely covers the fruit. The olives remain in this solution until the lye has penetrated two-thirds of the way through the flesh. The lye is then replaced by water, which removes any remaining residue and the process is repeated. Lengthy washing properly eliminates soda particles but also washes away soluble sugars, which are necessary for subsequent fermentation.

Fermentation is carried out in suitable containers in which the olives are covered with brine. Traditionally, this was done in wooden casks. More recently, larger containers have come into use that are inert on the inside. The brine causes the release of the fruit cell juices, forming a culture medium suitable for fermentation. Brine concentrations are 9-10%, to begin with, but rapidly drop to 5% owing to the olive's higher content of interchangeable water.

When properly fermented, olives keep for a long time. If they are in casks, the brine level must be topped up. At the time of shipment, the olives have to be classified for the first or second time as the case may be. The original brine is replaced and the olives are packed in barrels and tin or glass containers. Sometimes they are stoned (pitted) or stuffed with anchovies, pimento, etc. The most commonly used varieties in Spain are Manzanillo and Gordal.

But after discovering this you may be thinking, whoever came up with the idea of finding a way to eat a drupe that was at first sight totally inedible and had the patience to even work it out?

Well, it is a bit of a mystery but the general consensus is that it was the Romans who most likely came up with the technique that put the olive fruit itself on the dinner table. Earlier people had discovered that olives could be debittered by soaking them in repeated changes of water, a painstaking process that took many months and was probably discovered by accident. This was somewhat improved by fermenting the olives in brine, which was marginally quicker, but the Romans found that supplementing the brine with lye from wood ashes (sodium hydroxide) cut the time required for producing an edible olive from months to hours.

About 90 per cent of the world’s olive crop goes to make olive oil. The remainder is harvested for table olives which, though there are over 2,000 known olive cultivars, are known to most of us in two colours: green and black.

Green olives, the kind found in martinis, are picked green and unripe and then cured. These are often called Spanish olives, as mentioned earlier. Tree-ripened olives, left to themselves, turn purple - not black (as you can see in the image on the left) - due to an accumulation of anthocyanin, the same pigment that puts the purple in Concord grapes.

Black olives, though labelled as “ripe” on supermarket cans, actually aren’t: these, a California invention, are green olives that have been cured in an alkaline solution, and then treated with oxygen and an iron compound (ferrous gluconate) that turns their skins a shiny patent-leather black, so they are in fact manipulated and artificial in colour.

2

Like

Published at 2:38 PM Comments (1)

2

Like

Published at 2:38 PM Comments (1)

Tuna Casserole - A Basque Classic

Tuesday, April 21, 2020

Following my series of tuna posts, I thought a warm dish might be more attractive given the sudden turn in the weather recently. This tuna casserole is of Basque origin, a region whose cuisine is celebrated throughout Spain and the world as being one of the best. Known as "Marmitako", it is basically a tuna fish stew with potatoes that is not too difficult to make but is extremely tasty and filling.

The name Marmitako comes from the Basque word 'marmita' which means 'pot' or 'casserole' in the Basque language. This is combined with the suffix of the genitive case 'ko' to give Marmitako which literally means 'from the pot'. And that is precisely what this Spanish recipe is, a stew made in a pot. Of course, many dishes in Basque gastronomy are made in pots but clearly someone decided that this dish was deserving of the title.

Marmitako stew originally began life onboard the local fishing boats off the Spanish coast, and in many cases, still is. However, it has also been a staple dish of many Basque restaurants, something which you will see when you visit Spain, especially in Summer which is the fishing season for tuna.

There are a number of variations of the dish, which mainly vary due to the type of fish used in the recipe. One of the most popular varieties is the one that uses salmon instead of the traditional tuna. However, tuna tends to be the favoured ingredient as it was delicious, widely available and not that expensive!

This tuna fish stew is like a thick soup, which is in mostly due to the potatoes. The traditional method of 'cracking' the potatoes is done as it makes the potatoes release more starch into the stew. This also means that the fish soup is filling and a relatively small amount of ingredients can go a long way - perfect for those lovers of Spanish gastronomy on a budget!

Another great thing about Marmitako is that the main body of the stew can be prepared up to the point when you are about to add the tuna and will keep in a fridge overnight. You can then heat up the stew the next day and add the tuna then. This is what you will need:

Marmitako | Fresh Tuna and Potato Stew

Ingredients:

2 dried choriceros or ancho chilli peppers

1 lb fresh tuna fillet

Coarse salt

2 lbs of russet potatoes (around 4 potatoes)

⅓ cup Olive oil

1 yellow onion, chopped finely

1 clove garlic, crushed

½ green bell pepper, seeded and cut into long, thin strips

1 tbsp sweet pimetón or paprika

Serves 6 when eaten as a main course

Preparation:

Put the dried chilli peppers into a heatproof dish and cover with boiling water and leave to stand for about 30 minutes, or until the peppers are soft.

Then drain the chilli peppers, slit them open and scrape out the flesh and put to one side. Get rid of the seeds, skins and stems.

Cut the tuna fillet into small pieces and sprinkle them with the coarse salt and leave to one side.

Peel the potatoes and then 'crack' them by cutting a little way into each potato and then breaking it open the rest of the way. The pieces should be the same size as chestnuts. Leave the pieces of the potatoes to one side.

In a saucepan, heat the olive oil over medium-high heat then add the onion, garlic, bell pepper strips and the chilli pepper flesh. Stir the mixture well and cook for about 5 minutes or until both the onion and green pepper have begun to go soft and all the ingredients are mixed together nicely.

To this mixture, add the potatoes and pimetón and mix well. Season with some salt and add water to cover the ingredients by about 5 centimetres (2 inches). Bring to a boil and then cover. Once covered, reduce the heat to medium-low heat and then cook for another 30 minutes or until the potatoes feel soft when prodded with a fork.

Add the tuna to the pan and then simmer until the tuna is opaque around 5 minutes. Remove the stew from the heat and then allow to stand for half an hour before serving.

When you come to serve the stew, reheat it over a low flame to a sufficiently hot temperature. Ladle out into warm bowls and serve straight away.

Enjoy!

1

Like

Published at 7:16 PM Comments (1)

1

Like

Published at 7:16 PM Comments (1)

Tuna tartare - Barbate meets Japan

Thursday, April 16, 2020

The other day, while I was writing the article about Barbate and its red tuna industry I must admit my mouth started to water thinking of a fantastic red tuna tartare I ate in Valencia. It was absolutely spectacular and not at all “fishy” in flavour. I am not a great fish eater and I am very picky with fish, I don’t like the strong characteristic “fishy” taste that some fish have when you can actually taste the sea in the meat, so it is something that tends to make me choose meat or seafood and stick to a very small selection of mild fish such as cod, tuna or swordfish which I find meatier and also more filling. However I do consider myself gastronomically adventurous and I will try everything several times over, but in different places, just in case I find a recipe that changes my mind on a certain product. And this dish did exactly that. I was never a fan of raw fish before and I am still not, really, every time I go to a Japanese Restaurant I end up ordering Beef Teriyaki, Seafood and maybe some prawn and avocado Maki just for the wasabi, which I just love. But when I tasted this red tuna tartar I was absolutely taken by it and another speciality dish was added to my list of favourites.

11.40.39 - Copy 1.png) I thought I would share this very simple and very elegant recipe with you all, as it is a real stunner of a dish at any dinner party or just as a light lunch. It is so simple to make, so full of flavour. For this recipe, as all ingredients are raw, make sure you use a good quality extra virgin olive oil, it will make all the difference and one that is not bitter, such as an Arbequina or a Serrana de Espadán both have a very low pungency. The bitterness will overpower the dressing and the flavour of the avocado and the tuna. So taste the oil before you mix it in. I thought I would share this very simple and very elegant recipe with you all, as it is a real stunner of a dish at any dinner party or just as a light lunch. It is so simple to make, so full of flavour. For this recipe, as all ingredients are raw, make sure you use a good quality extra virgin olive oil, it will make all the difference and one that is not bitter, such as an Arbequina or a Serrana de Espadán both have a very low pungency. The bitterness will overpower the dressing and the flavour of the avocado and the tuna. So taste the oil before you mix it in.

Ingredients (2 servings):

300 g of Red Tuna loin (or sushi-grade tuna)

120g of Avocado

20g of Shallots

20g of Chives

30g of Peeled Tomatoes

10g Sesame Seeds

Lime Zest

(If the tuna is ‘fresh’ from the market it is important to freeze it for 48 hours to kill any parasites such as Anisakis)

All of these ingredients should be diced and the shallots should be very finely chopped. The chives should be chopped coarsely. Place all the ingredients together in a bowl, finely grate a small amount of lime peel over the ingredients and mix them up. I have never weighed the lime peel so I have no idea how much it is, I just do it by sight as if I was seasoning with salt. So it is just a little amount to give the flavour a little kick! Reserve a little of the sesame seeds and the chives to decorate the dish at the end. (You can mix the diced tuna, sesame seeds, tomato, chives and shallots and then layer the avocado separately if you prefer for presentation purposes.)

Now we need to make the marinade for we will need the following ingredients:

10ml Extra Virgin Olive Oil

20ml Soy Sauce

2ml Sesame Oil

10ml Jerez ‘Sherry’ Vinegar (If possible from the variety Pedro Ximenez, it is sweeter)

2 Teaspoons Wholegrain Mustard or a 1 teaspoon of Wasabi. (This should be added according to taste preference, whichever you prefer. If you don’t like either, this ingredient can be removed and it will still be fantastic)

Pour all the ingredients into a bowl to make the marinade and whisk it all together.

Use a tablespoon to pour some of the marinade over the diced ingredients. Mix the marinade through the ingredients adding little by little until it is all well covered. Taste and season with salt if necessary. Let it stand to marinate for about half an hour and then serve. A great way of serving this dish is as a 'timbale'. If you have a ring mould great but if you don’t you can use a section cut out from a plastic water bottle to serve as a mould, I didn’t and this solution worked just fine!

Take the mould, fill it with the marinated mixture and pour a couple of teaspoons of the marinade over the mixture in the mould (if you are layering the avocado place the cubes at the bottom). Carefully remove the mould and sprinkle the remaining sesame seeds and chives over the top and Listo! Ready to eat! If you want slightly more sauce just pour a couple of spoons into the base of the bowl.

I hope you enjoy it, I certainly did!

2

Like

Published at 9:25 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 9:25 PM Comments (0)

The Mecca for Tuna

Friday, April 10, 2020

When the first full moon of May arrives, the large ‘Bluefin Tuna’ or the ‘Red Tuna’ as it is referred to here, in Spain, migrate from the cold waters of the Atlantic to the warmer Mediterranean in order to reproduce. For years the environmental movement has warned of the danger of extinction of this species due to over-fishing. An agreement on the catch quota does not leave anyone completely satisfied but it is difficult to balance the requirements to preserve resources and preserve a fishing tradition and consumption that dates back thousands of years, especially when certain methods of fishing are far more ecological than others and less aggressive.

International negotiations on Bluefin tuna catches have resulted in less than a 4% increase in quota for this year. The Bluefin tuna is considered ‘ La Pata Negra of the Sea’ in Spain and is one of the most highly prized fish used in Japanese raw fish dishes. About 80% of the Atlantic and Pacific Bluefin tuna is consumed in Japan. Bluefin tuna sashimi is a particular delicacy in Japan and ‘Red Tuna Tartar’ a gastronomic speciality in Cadiz. All tuna were definitely not born equal.

Not all species of the tuna family are equally appreciated from a gastronomic point of view but the Bluefin tuna is the protagonist and the most acclaimed of all is the ‘Red Tuna of Almadraba’ caught on the coast of Cadiz in the Straights of Gibraltar. La Almadraba is an art that dates back 3,000 years and is considered the most ecological and sustainable method used to date, as it permits individual selection and the fish that are set free are not injured in any way.

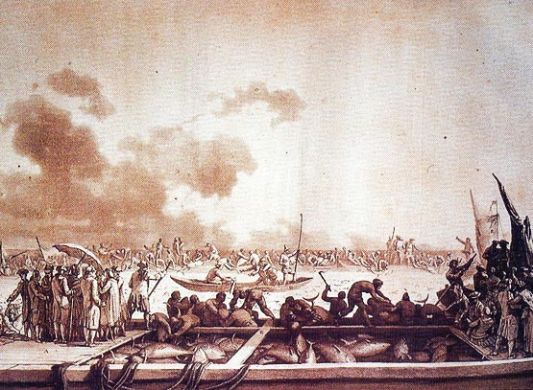

The word Almadraba comes from the Andalusian Arabic word Almadrába, which means a place where one is hit or fights. This technique has its roots dating back to the time of the Phoenicians and even the Romans fed their legions on this migrating tuna. It uses a complex and labyrinthine net system that sinks more than 30 meters deep. It is funnel-shaped and located on the migratory path of the Bluefin tuna, usually near the coast and then pulled up by hand (La Levantá) so the fish come to the surface where they can be selected according to size and the rest are then returned to the Sea (La Bajá).

The fishermen join their boats to form a circle and while all the Bluefin are raging around on the surface, the fishermen are pulling them out of the water by hand, many of them weighing over 200Kg. It is quite a spectacle. This method is truly artisan and is of unquestionable effectiveness and has no consequence to the environment unless too many fish are captured but the Almadrabas are the leading source of information on the control of the species and were the first to give the alarm when numbers started to drop. As opposed to other methods used throughout the Atlantic and Pacific that include industrial nets and lines trapping enormous quantities of tuna of all ages and all sorts of marine life along with them. On some occasions in other countries, even explosives are used to speed up the process, killing everything around. The following video will help understand how the Almadraba actually works.

The Red Tuna of Almadraba is caught when it returns from northern Europe, after spending the winter off the freezing coasts of countries like Norway and Iceland, on the arrival of the Spring and Summer, between May and June, it sets off to the Mediterranean to reproduce in the warmer and less turbulent waters. Like all migratory animals, the Red Tuna builds up its energy reserves and fattens up as much as possible before setting out on that immense Odyssey of thousands and thousands of miles. When it appears on the Andalusian coast its meat has obtained an optimum level of fat and it is at this point when the meat is most succulent.

The Red Tuna of Almadraba can be caught ‘on the way in’ or ‘on the way out’, depending on when it passes through the Strait of Gibraltar. The return journey to northern Europe is in the months of September and October but the ‘first leg’ of the trip delivers the best quality fish and is usually dedicated in its entirety to ‘fresh’ consumption as the tuna on the way back carry less fat and the meat is dryer. Most of this ‘first catch’ is sold to Japan where they queue up to buy the Red Tuna of Almadraba. In the central market of Tsukiji (Tokyo) this tuna goes on sale to the public at well over 90 Euros a kilo and on occasion much much more. Here in Spain this year it is exported from the fishing market at around 20 Euros a kilo. A very pricey fillet by the time it reaches the consumer.

The importance of this fish and the techniques used to catch it are little known in Spain but there is a growing awareness of its value in the municipalities where you can find an Almadraba such as Conil, Barbate, Tarija and Zahara de Los Atunes where they are already boosting its gastronomic and touristic appeal.

Once the Red Tuna have been captured they are taken away to be cut up and filleted. This in itself is another art form that has been passed down over the generations and is called “El Ronqueo” because of the noise the knife makes when separating the different parts of the Bluefin. It is a hoarse grunting sound almost like the grunt of a pig caused by the knife running along the spines as they slice through the meat. It is quite impressive how they cut up a fresh Tuna in such a short time taking advantage of virtually every part of the fish and leaving just the bones, separating all the different cuts manually. Even the Japanese who are masters with their knives come to Cadiz to see the Masters of the Ronqueo and even pay more if certain reputable people have cut up the fish. It is quite a spectacle but certainly not for sensitive audiences. So who would have thought that one of the most sought after fish in Japan is actually captured in Spain?

2

Like

Published at 7:15 PM Comments (2)

2

Like

Published at 7:15 PM Comments (2)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|