Spanish Flu & Coronavirus

Tuesday, March 31, 2020

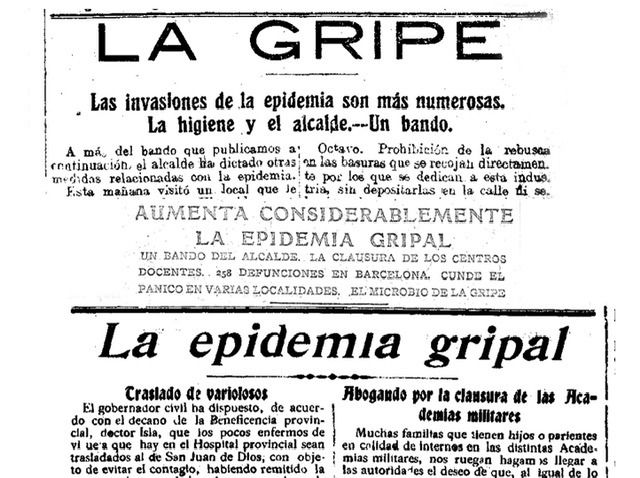

The initial response to the 1918 outbreak was to play it down, and later efforts at disinfection and social distancing proved insufficient to stop the spread of a disease that killed over 147,000 in Spain in one year.

When the new flu-like disease emerged, the initial response in Spain was to laugh it off. On May 22, 1918, the front page of the Spanish newspaper ABC reported on a new illness, described as similar to the flu but with milder symptoms. That same month, Madrid held its annual San Isidro festivities, providing the perfect conditions for mass contagion.

With World War I still raging, countries involved in the conflict did not report on the disease to keep morale up and avoid providing the enemy with an edge. But Spain, which remained neutral in the conflict, was free to flag it up, which is why the 20th-century pandemic, which killed more than 50 million people worldwide, was nicknamed the “Spanish flu” even though its origin was not in Spain.

The 1918 influenza pandemic showed both significant differences and stunning similarities with today’s coronavirus crisis. As with the current virus, the situation in 1918 was exacerbated by the fact that it was not immediately taken seriously, and the erratic response by health officials eroded their authority in the eyes of citizens and the press, which questioned the government’s every decision.

And just like today’s coronavirus, the influenza outbreak showed no respect for hierarchies, with both King Alfonso XIII and the head of government, Manuel García Prieto, falling ill.

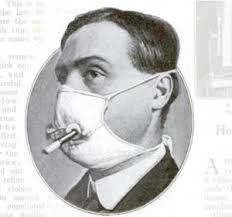

In 1918, half of Spain’s inhabitants were illiterate and the infant mortality rate was twice that of today’s poorest countries. Yet many measures implemented to contain the epidemic were similar to those being employed today. Universities and schools were closed, and rail travel was controlled, with disinfection teams deployed along railroad lines in an effort to contain the spread of the virus. There were also local authorities who were reluctant to impose restrictions; the mayor of Valladolid, for example, dragged his feet when it came to cancelling the fiestas in September, fearing the financial impact on the city’s business fabric.

Similarly, there was little that doctors could do apart from helping the sick to survive, although the techniques were much more rudimentary. Several experimental vaccines were tested without success, and some doctors even tried bloodletting despite the fact that such a practice had been discredited for a century. The Spanish began to wonder if doctors and scientists had any clue about what was going on.

With science failing to provide any answers, many turned to God. In Zamora, one of the hardest-hit provinces, Bishop Álvaro Ballano told his flock that the evil that was hanging over them was a consequence of their sins and lack of gratitude, and that is why the vengeance of eternal justice had fallen upon them.

To placate God, he organised one Mass after another in the provincial capital’s cathedral, probably facilitating the spread of the virus, and he confronted the health authorities which sought to ban them. In this respect, times have changed and bishops are not only respecting the advice from the health authorities but also making sure it reaches the faithful, limiting attendance at funerals to immediate family members.

.jpg)

The first stage of infection in 1918, equivalent to where we are with the coronavirus, was in fact not the most deadly. With the arrival of summer, the epidemic subsided, but in the fall it returned with a vengeance. The health system was overwhelmed, and at a time when many people were still living in the countryside, rural doctors were scarce; when they died, they were rarely replaced. Then as now, volunteers were recruited from among medical students.

The official death toll of the 1918 flu in Spain, a country of just over 20 million inhabitants at the time, was terrifying. In 1918 it killed 147,114 people; the following year, it took 21,245 lives and in 1920, it killed 17,825. The epidemic lasted three years and it particularly targeted people in their 20s who were completely healthy. The official death toll of the 1918 flu in Spain, a country of just over 20 million inhabitants at the time, was terrifying. In 1918 it killed 147,114 people; the following year, it took 21,245 lives and in 1920, it killed 17,825. The epidemic lasted three years and it particularly targeted people in their 20s who were completely healthy.

The supply of coffins in some Spanish cities ran out, and the mayor of Barcelona asked for the army’s help in transporting and burying the dead. This has not been the case yet in Spain, but it has in Italy, which is a week ahead in terms of the evolution of the pandemic. On March 18, dozens of coffins in the local cemetery in Bergamo were loaded onto army trucks to be taken to less affected areas for cremation.

The Spanish population fell only twice during the 20th century. In 1918, there was a net loss of 83,121 people and in 1939, it lost 50,266 due to the Civil War...

0

Like

Published at 4:38 PM Comments (6)

0

Like

Published at 4:38 PM Comments (6)

The Spanish Guitar - A brief history

Friday, March 13, 2020

The name "guitar" comes from the ancient Sanskrit word for "string" - "tar". (This is the language from which the languages of central Asia and northern India developed.) Many stringed folk instruments exist in Central Asia to this day which have been used in almost unchanged form for several thousand years, as shown by archeological finds in the area. Many have names that end in "tar", with a prefix indicating the number of strings for example: The name "guitar" comes from the ancient Sanskrit word for "string" - "tar". (This is the language from which the languages of central Asia and northern India developed.) Many stringed folk instruments exist in Central Asia to this day which have been used in almost unchanged form for several thousand years, as shown by archeological finds in the area. Many have names that end in "tar", with a prefix indicating the number of strings for example:

two = Sanskrit "dvi" - modern Persian "do" -

dotar: two-string instrument found in Turkestan

three = Sanskrit "tri" - modern Persian "se" -

setar: 3-string instrument, found in Persia (Iran),

(cf. sitar, India, elaborately developed, many-stringed)

four = Sanskrit "chatur" - modern Persian "char" -

chartar, 4-string instrument, Persia (most commonly known as "tar" in modern usage)

(cf. quitarra, early Spanish 4-string guitar, modern Arabic qithara, Italian chitarra, etc)

The Indian sitar almost certainly took its name from the Persian setar, but over the centuries the Indians developed it into a completely new instrument, following their own aesthetic and cultural ideals. The Indian sitar almost certainly took its name from the Persian setar, but over the centuries the Indians developed it into a completely new instrument, following their own aesthetic and cultural ideals.

The guitar's ancestors came to Europe from Egypt and Mesopotamia. These early instruments had, most often, four strings - as we have seen above, the word "guitar" is derived from the Old Persian "chartar", which, in direct translation, means "four strings". Many such instruments, and variations with from three to five strings, can be seen in mediaeval illustrated manuscripts, and carved in stone in churches and cathedrals, from Roman times through till the Middle Ages.

By the beginning of the Renaissance, the four-course (4 unison-tuned pairs of strings) guitar had become dominant, at least in most of Europe. The earliest known music for the four-course "chitarra" was written in 16th century Spain. The five-course guitarra battente first appeared in Italy at around the same time, and gradually replaced the four-course instrument. The standard tuning had already settled at A, D, G, B, E, like the top five strings of the modern guitar.

In common with lutes, early guitars seldom had necks with more than 8 frets free of the body, but as the guitar evolved, this increased first to 10 and then to 12 frets to the body.

A sixth course of strings was added to the Italian "guitarra battente" in the 17th century, and guitar makers all over Europe followed the trend. The six-course arrangement gradually gave way to six single strings, and again it seems that the Italians were the driving force.

In the transition from five courses to six single strings, it seems that at least some existing five-course instruments were modified to the new stringing pattern. This was a fairly simple task, as it only entailed replacing (or re-working) the nut and bridge, and plugging four of the tuning peg holes. In the transition from five courses to six single strings, it seems that at least some existing five-course instruments were modified to the new stringing pattern. This was a fairly simple task, as it only entailed replacing (or re-working) the nut and bridge, and plugging four of the tuning peg holes.

At the beginning of the 19th century one can see the modern guitar beginning to take shape. Bodies were still fairly small and narrow-waisted.

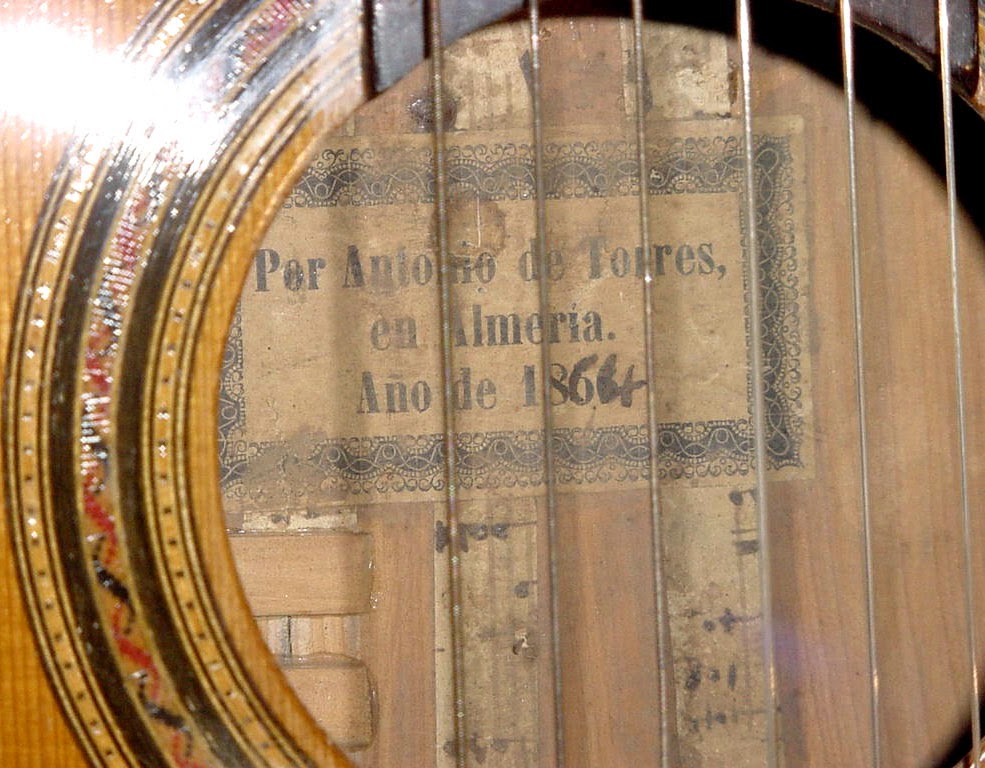

The modern "classical" guitar took its present form when the Spanish maker Antonio Torres increased the size of the body, altered its proportions, and introduced the revolutionary "fan" top bracing pattern, in around 1850. His design radically improved the volume, tone and projection of the instrument, and very soon became the accepted construction standard. It has remained essentially unchanged, and unchallenged, to this day.

0

Like

Published at 9:38 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 9:38 PM Comments (0)

One of Spain's Most Important Cathedrals

Tuesday, March 3, 2020

One of the finest examples of Spanish Gothic art. This cathedral is outstanding for the elegance and harmony of its architecture, and it is the only one in Spain which, for its cathedral building alone, has received the UNESCO World Heritage designation. Although it is predominantly Gothic, the cathedral also displays other artistic styles, given that it was built over a period lasting from 1221 to 1795. Its main façade is the Puerta del Perdón, with a starred rose-window and a gallery of statues of the Castile monarchs.

On either side are its 84-metre towers, crowned by magnificent 15th-century spires with open stonework traceries. Its most beautiful group of sculptures, however, is to be found on the Puerta del Sarmental façade, with the image of a Pantocrator surrounded by the apostles and evangelists. Inside, special mention should be made of the dome of the main nave, topped with a beautiful Mudéjar vault. Beneath it lies the remains of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, known as ‘El Cid Campeador’, and his wife, Doña Jimena.

Close by, you will find the beautiful Escalera Dorada golden staircase by Diego de Siloé, built in the 16th century and inspired in the Italian Renaissance. In the side-naves of the cathedral, there are 19 chapels, with the Condestable and Santa Tecla chapels standing out especially. There are also valuable works of art to be enjoyed: a unique collection that includes altarpieces, paintings, choir stalls, tombs and sculptures, amongst other objects.

0

Like

Published at 6:43 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 6:43 PM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|