As Safe as it Gets..

Friday, September 27, 2024

"Next stop, Banco de España." When you travel on line 2 of the Madrid metro and approach this station, little would you know that just a few meters away you can find one of the best-kept treasures in Spain, the Bank of Spain's gold deposit chamber? A chamber that contains a third of Spain’s total reserve of this precious metal.

The central headquarters of the Bank of Spain is one of the most representative buildings of Madrid and of the Spanish architecture of the 19th and early 20th centuries. For the construction of the current headquarters of the Bank of Spain, the palace of the Marquis of Alcañices was acquired in 1882, located on Calle de Alcalá around the Paseo del Prado. The first stone was laid on July 4, 1884, in a ceremony attended by King Alfonso XII and the monumental building was inaugurated in 1891.

Construction of the vault for the safekeeping of the gold began in late 1932 and was completed in two and a half years, with 260 workers working three shifts. Its approximate cost was nine and a half million pesetas. The inauguration took place shortly before the Civil War, during which it served as a refuge from the bombings for the families who inhabited the bank building.

The chamber is 35 meters deep and its surface is 2,500 square meters. Its design seems to be inspired by a similar construction of the vault of the Vienna Savings Bank.

The construction is made of reinforced concrete and molten cement, and to carry it out it was necessary to pipe and divert the waters present in the subsoil, some 25 meters deep, as it pressed on the walls of the chamber. This water corresponds to the Las Pascualas stream, which runs almost at surface level along the Castellana and which was, in its day, channelled underground, running down Calle Alcalá and feeds into the fountain of Cibeles.

Access to the chamber is through several armoured doors, the first of which weighs around 16 tons and was manufactured in Pennsylvania, USA, by Cofres Forts York (York Safe & Lock Company). The other smaller doors, but also armoured, were manufactured by the same company. Its weight ranges between 15 and 8 tons. To carry out the descent of these doors down into their position, steel cables were used that could only be used once, due to the wear they suffered when supporting the immense weight of the doors.

The armoured door has a very small tolerance, of tenths of a millimetre, so that even the slightest impurity in the arch prevents it from fitting correctly and the anchor points from being activated. In addition, the door is made of steel, but not stainless, so care must be taken to maintain it, and it should always be covered with a thin layer of petroleum jelly to prevent it from rusting.

The gold chamber houses the numismatic collection of the Bank of Spain, only comparable to the collections of the Archaeological Museum or the Royal Mint, and part of the gold reserves. Inside it, a third of the Spanish gold reserve is stacked on shelves made by the engineer Eiffel. Some even say that the chamber could contain 38 Nazi gold bars with which Switzerland paid Spain between 1941 and 1945 and that they have the III Reich shield with its swastika printed on them.

What is clear is that most of the coins that make up this collection come from popular subscriptions made during the Civil War, donations, sometimes voluntary, for the financing of the army and the deposits constituted from 1937, as a result of the Decree of Nationalization of Foreign Exchange and Gold. This Decree obliged all citizens to deliver the gold in paste or coin that they had in their power to replace the gold reserves that the republican government had sent to Moscow as payment for war supplies.

These deliveries were made in the form of deposits and most of them are not recoverable because the depositors chose to collect in cash the gold value of their coins. Others, whose coins had a higher numismatic or sentimental value, preferred to keep the deposit in the hope of recovering them when the regulations allowed. Some of the latter are still being returned, provided that the claimant can prove his right to the deposit.

The collection, of great numismatic value, is made up of more than half a million pieces and includes coins of very diverse origin since it collects not only the numismatic history of the Iberian Peninsula but there are also Greek, Roman, Byzantine pieces, from Hispanic America, French or British. It also has a complete collection of gold dollars, minted since the 17th century. There is also a less numerous collection of silver pieces.

The Bank of Spain owns 9.1 million troy ounces of gold, according to 2014 data, which are deposited in its own vaults and in three other places abroad, including the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, for reasons of logistical ease, in case it was necessary to mobilize these reserves. Another place where part of the gold is conserved is Fort Knox, in the United States. A standard gold bar weighs 400 troy ounces, just under 12 and a half kilos.

To get to the vault, you have to overcome various obstacles and as you can imagine, it is not very easy. That said, it sounds like an adventure for Indiana Jones and this location is the used in the new season of the Money Heist!

- The first obstacle is a 16-ton steel door. To open the door, three keys are necessary: those of the general manager, the controller and the cashier.

- Then you reach a fortified elevator that is the only way to descend through a vertical tunnel of 36-38 meters. Of course, you need a different key to use the elevator.

- Once down, you go through an underground corridor until you reach another 14-ton steel door.

- Once through that door, there is a moat. To cross it you have to use a retractable bridge as in the Middle Ages.

- Behind the bridge is another 8-ton armoured door. This is the access to the vault that contains the gold. In addition to this, there are sensors, cameras and all kinds of surveillance devices.

If an alarm were to go off, all doors would automatically close and the moat would be completely flooded within minutes thanks to the underwater stream channelling into the fountain of Cibeles. The police or the army would arrive in less than 5 minutes and it would all be over.

But ultimately it is Cibeles who is safeguarding Spain’s gold!

Not once has anyone ever attempted to rob the Bank of Spain.

Inside the original building from 1891, the main staircase and the patio stand out, which was the general reception area and which today occupies the library, to which a cast-iron structure was added, commissioned from the Mieres Factory.

The monumental Carrara marble staircase, which is accessed from the Paseo del Prado door, is a sample of the most traditional architecture, designed by the Bank's architects and executed by Adolfo Areizaga from Bilbao. Next to it are magnificent Symbolist-style stained glass windows commissioned from the German company Mayer, with numerous allegorical figures.

With the expansion decided in 1927 and completed in 1934, the new operations yard, with a height of 27 meters and an area of about 900 square meters, departs from the classic concepts and includes some examples of Art Deco, such as the upper window or the clock, a decorative and functional piece located in the centre of the patio. Also noteworthy is the roundabout, which serves as an interior link between the two buildings.

3

Like

Published at 11:27 PM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 11:27 PM Comments (0)

Discover The Carapucho - Galicia's most unusual Raincoat

Saturday, September 21, 2024

Drawing upon the rich tapestry of traditional Galician life, the Carapucho emerges not merely as a garment but as a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of the Galician people, especially the rural populace. This unique creation, fashioned from straw, reflects a harmonious blend of necessity and artistry, deeply embedded in the historical narrative of Northern Spain.

The Essence of Carapucho

The rural areas of Galicia have always been subject to harsh environmental conditions, with cold rains characterising much of the year. The Carapucho was born out of a practical need to shield oneself from these relentless downpours. However, its significance transcends its utility, marking a cultural identity that has weathered the storms of time.

Crafted from straw, the Carapucho served as a makeshift raincoat for peasants. This material choice was no accident; straw was readily available and offered effective waterproof characteristics, making it an ideal resource for protective clothing in a pre-industrial context. The craftsmanship involved in creating a Carapucho demonstrates a profound understanding of the materials at hand and a creative spirit that turned simple agricultural byproducts into a vital part of everyday life. The process of making a Carapucho involved more than merely fashioning a hat or a cloak; it was a meticulous craft that required patience, skill, and a deep connection with the natural environment. The peasants would gather straw or reeds, materials that were in abundant supply across the Galician countryside. These were then intricately woven together to form a coherent structure. The result was not only functional, protecting the wearer's entire head and, in some cases, even the shoulders and upper body from the rain, but also allowed for free movement, which was crucial for working outdoors.

Moreover, the creation of the Carapucho was a communal activity, reflecting the collectivist spirit of rural Galicia. It was common for families or groups of neighbours to come together, sharing techniques and stories as they worked. This not only facilitated the practical transmission of knowledge across generations but also strengthened community bonds. Each Carapucho, therefore, was imbued with a sense of shared identity and collective resilience.

Beyond Practicality: Symbolism and Identity

While the primary function of the Carapucho was undeniably practical, its cultural significance cannot be overstated. In a region where weather could dictate the rhythm of daily life, the ability to carry on work regardless of the elements was both a necessity and a point of pride. The Carapucho came to symbolise the hardiness of the Galician people, embodying their unyielding spirit and close relationship with the land.

As industrialisation and modern advances introduced new materials and clothing options, the use of the Carapucho in its traditional form diminished. However, it remains a potent symbol of Galician heritage, evoking memories of a time when life was intimately tied to the rhythms of nature and community was forged in the face of adversity.

The Carapucho Today

In contemporary times, the Carapucho holds a special place in the cultural memory of Galicia. While no longer a common sight in the fields, it endures as an emblem of Galician identity, celebrated at cultural events and festivals. Artisans and historians alike continue to explore and preserve the techniques used to create these remarkable garments, ensuring that the knowledge does not fade into obscurity.

The Carapucho is much more than a historical curiosity; it is a vibrant thread in the fabric of Galician culture, representing the convergence of necessity, creativity, and community.

1

Like

Published at 11:25 AM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 11:25 AM Comments (0)

Zaragoza's National Monument: The Aljafería

Saturday, September 14, 2024

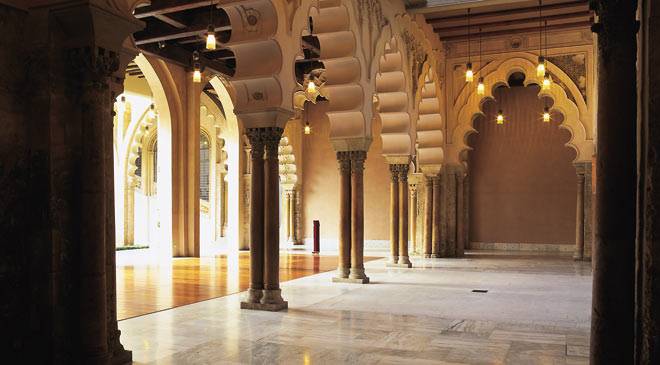

The Aljafería in Zaragoza was declared a National Monument of Historical and Artistic Interest on the 4th June 1931. In 1947, however, it still remained a woeful sight in rags, according to the architect Francisco Íñiguez Almech, who for over thirty years undertook a slow and thorough recovery task. After his death in 1982, this was continued by the architects Ángel Peropadre Muniesa, Luis Franco Lahoz and Mariano Pemán Gavín. The result of all these alterations, backed by several archaeological digs, has led to the present-day appearance of the building, in which the original remains can be distinguished from the reconstructed part.

Moreover, the Regional Assembly of Aragon has its seat in one section of this collection of historical buildings. Work on the Assembly building was started in 1985 by the architects Franco and Pemán. This work is part of the aesthetic trends of contemporary architecture, and its authors have avoided including historical elements that could lead to possible mistaken interpretation. In 2001, UNESCO declared the Mudejar architecture of Aragon a World Heritage site, and praised the Aljafería palace as one of the most representative and emblematic monuments of Aragonese Mudejar Architecture.

This retains part of the primitive fortified enclosure on a quadrangular floor plan reinforced by great ultra-semicircular turrets, together with the prismatic volume of the troubadour Tower, whose lower part, which dates from the IX century, is the most ancient part of the architectonic building.

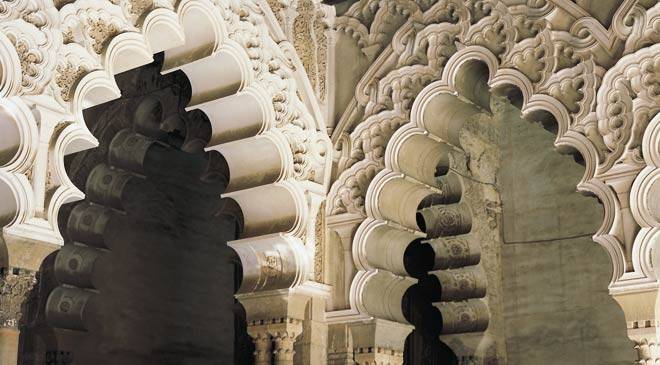

The Islamic Palace enclosure houses residential quarters in its central area which are similar to the typological model of the 'omeya' influenced Islamic palaces, just like those that had developed in the Moslem palaces in the desert (which date back to the VIII century). So, in contrast to the defensive spirit and the strength of its walls, the 'taifal' palace, which is of delicate ornamental beauty, presents a composite plan based on a great rectangular open-air courtyard with a pool on its southern side. Next come two lateral porticoes with a polycusped mixed line series of arches that acts as visual screens and at the far end some tripartite rooms, which were originally intended for ceremonial and private use. There is also a small oratory in the northern portico, with a small octagonal floor plan, in whose interior fine and lavish plaster decorations can be seen (with typical ataurique motifs) as well as some brightly coloured well contrasted pictorial fragments, which are of particular interest. All of these artistic achievements correspond to the work carried out during the second half of the XI century under the command of Abu-Ya-far Ah-mad ibn Hud al-Muqtadir, and they serve to highlight the cultural importance and the rich virtuosity of his court. Furthermore, the Aljafería is thought to be one of the greatest pinnacles of Hispano-Moslem art, and its artistic contributions were later copied at the Reales Alcazares in Seville and at the Alhambra in Granada.

The palace of the Catholic King and Queen was erected on top of the Moslem structure in around 1492, to symbolise the power and prestige of the Christian monarchs. However, the direction of the work fell to the Mudejar master, Faraig de Gali. The work blended the medieval artistic inheritance with the new Renaissance contributions. From this origin came some of the most significant examples of the so-called Reyes Catolicos style (that of the Catholic King and Queen).

The palace comprises a flight of stairs, a gallery or corridor and a collection of rooms known as The Lost Steps, which lead to the Great Throne Room. Of these, the most interesting are, on the one hand, the paving made up of small paving tiles and the tiles from Muel, and on the other, the gold and polychrome wooden ceilings among which the magnificent coffered ceiling in the Throne Room is especially remarkable.

From 1593, by order of King Phillip II, the Siennese engineer Tiburcio Spanochi drew up plans to transform the Aljafería into a modern style fort or citadel. Consequently, he provided the buildings with an outer walled enclosure with pentagonal bastions at the corners and an imposing moat surrounding it all (with slightly sloping walls and corresponding drawbridges). However, the real reason for building this fort was none other than to show royal authority in the face of the Aragonese people’s demands for their rights as well as the monarch’s wish to curb possible revolts by the people of Zaragoza. After this first military renovation, throughout the XVIII and XIX centuries, extensive alterations were made to the building to adapt it for its use a barracks. To this day the blocks built during the reign of Charles III remain, along with two of the NeoGothic turrets added during the time of Isabel II.

Lastly, it must be must be pointed out that very few Aragonese monuments have as many excellent architectonic examples such as those at the Aljafería in Zaragoza, summing up ten centuries of daily life as well as historic and artistic events in Aragon.

0

Like

Published at 1:46 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 1:46 PM Comments (0)

The Capital of Spain - constantly on the move...

Friday, September 6, 2024

Although there are those who still think that Madrid has always been the capital of Spain, the truth is that it has not. Throughout the history of the country and for different historical reasons throughout it, the capital moved in the past to other cities such as Toledo, Valladolid, Cádiz or Valencia, among others. All this together with the first capitals that were part of the peninsula at the time of ancient Visigothic Hispania, at the time of the Roman Republic or at the beginning of the Kingdom of Spain that originated after the reconquest in Covadonga (Asturias). These are the cities that have been the capital of Spain: Although there are those who still think that Madrid has always been the capital of Spain, the truth is that it has not. Throughout the history of the country and for different historical reasons throughout it, the capital moved in the past to other cities such as Toledo, Valladolid, Cádiz or Valencia, among others. All this together with the first capitals that were part of the peninsula at the time of ancient Visigothic Hispania, at the time of the Roman Republic or at the beginning of the Kingdom of Spain that originated after the reconquest in Covadonga (Asturias). These are the cities that have been the capital of Spain:

Cordoba

Córdoba was founded by the Romans during the second century BC, and it also became the capital of Hispania in times of the Roman Republic, as well as the Betica province during the Roman Empire. But its moment of splendour as a capital occurred during the Muslim domination of the Iberian Peninsula when it rose as the capital of the Emirate of Córdoba. A history that has also led it to become the city that houses the most titles of World Heritage Sites and thanks to authentic treasures that still live on today such as the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba, its historic centre, the Fiesta de Los Patios or the palatine city of Medina Azahara, among others.

Barcelona

Barcelona was the first capital of Hispania Goda and it was reinstated several times specifically during the Visigothic period. Known at that time as Barcino, present-day Barcelona was a Roman city until the arrival of the Goths. Few remains from that Visigoth period are currently preserved in Barcelona, but most of what has been preserved can be seen in the archaeological basement of the Barcelona History Museum. Another important moment in the history of the city would be in 1937 when, in the middle of the Civil War, it was decided to move the headquarters of the Republican Government to Barcelona.

Cangas de Onís

In addition to being known as one of the must-see visits if you travel to Asturias, as well as for the Covadonga Cave, the Basilica and the famous lakes of Covadonga, Cangas de Onís was the first capital of Asturias and according to Asturians, it was also the first capital of the Kingdom of Spain. It was precisely in Covadonga where Don Pelayo won the battle against Muslim troops in 722, thus initiating the Reconquest. In Cangas de Onís, Don Pelayo first established the capital of the Kingdom of Asturias and later that of Spain.

Toledo

Toledo has had its role as capital in two moments in history. The first was in the year 567 when King Atanagildo decided to move the capital of the Spanish Visigothic Kingdom from Barcelona to Toledo. In this way, Toledo became the capital of the Kingdom of Spain. Hundreds of years later, between 1519 and 1561, Toledo once again became the capital of the Spanish empire with Carlos V, but they would finally end up in 1561 with the Cortes moving to Madrid.

Madrid

The history of Madrid as capital begins in May 1561 when Felipe II makes the decision to establish the Court permanently in this city. A decision that would forever change the history of the city, which at that time was just one more city in the kingdom. One of the main reasons associated with this decision is the geographical centrality of Madrid with respect to the rest of the peninsula, although this change has also been linked to political and love affairs on the part of Felipe II.

From this moment the accelerated growth of this city began, although it should be noted that between 1601 and 1939 the Cortes passed in different periods of time from Madrid to other cities such as Valladolid, Seville, Cádiz, Valencia or Burgos, the latter two, coinciding with the instability of the Spanish Civil War. It is finally in 1939 when the capital city returns permanently to Madrid.

Valladolid

For the city of Valladolid, history took an unexpected turn in 1601 after the advisor of Felipe III, the Duke of Lerma, managed to transfer the Court of Madrid to Valladolid. An unexpected event that made Valladolid the capital of the Empire from 1601 to 1606. An event that also brought this city its moment of maximum splendour.

Seville

Seville was the capital of Spain specifically for two years and at the same time that the Napoleonic wars occurred (between 1808 and 1810). In those years, a large part of Spanish territory was invaded by Napoleon's troops and Seville was one of the places where they fought with the greatest force against these troops. It was specifically on December 16, 1808, when Count Floridablanca, president of the 'Junta Central', summoned the Junta to Seville, from which time Seville became the Spanish capital, the Real Alcázar being the headquarters of the 'Junta Central'. This came to an end in January 1810 when Seville finally surrendered to the French army.

Cadiz

In addition to being the oldest city in Spain and also in Europe, its foundation being located eighty years after the Trojan War around the 13th century BC, Cádiz also became the capital of Spain after the transfer of the Cortes and after the handover of Seville to the French. Its period as capital city ran from 1810 to 1813 and it was in this city where the Spanish Constitution of 1812, La Pepa, was proclaimed.

Valencia

Valencia also experienced its time as the capital of Spain, something that occurred between November 1936 and October 1937, after the Council of Ministers made the decision to move the capital and due to the dangerous approach of Franco's troops to Madrid. A moment in history that corresponded to the Second Republic and in the midst of the Civil War. A new capital that happened from one day to the next. The current headquarters of the Cortes, the Palacio de Los Borja, was converted to the republican centre of operations.

Burgos

After the government of the Republic moved between 1936 and 1939 from Valencia, to Barcelona and Gerona and Figueras, finally, Burgos ended up holding the capital of Spain between April 1 and October 18, 1939, coinciding with the end of the Spanish Civil War. This resulted in Burgos becoming the capital of nationalist Spain after the coup against the Republic.

4

Like

Published at 11:07 PM Comments (0)

4

Like

Published at 11:07 PM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|