12 Grapes on New Year's Eve - Why?

Friday, December 27, 2024

Traditions have always aroused a lot of curiosity in me because there is always a reason for them, nothing just happens by chance. Every year I celebrate the tradition of the New Year's Eve grapes and many years ago I wondered why they actually did this and nobody really seemed to know why. Still, to this very day, I am yet to meet a Spaniard who knows the story..... so I always end up telling it, every year!

The very short version of the story, which is pretty much common knowledge, is that wine farmers from Alicante and Murcia promoted the tradition in 1909. They were eager to sell on their large surplus of grapes from the incredible harvest they had had that year. However, although this story has some truth to it, the real origin dates back even further.

If we define the tradition of the New Year's Eve grapes as when twelve grapes are eaten in the Puerta del Sol at 12 am on December 31, which is basically the general understanding, the first written testimony of this goes as far back as January 1897 when the Madrid Press published that in "Madrid it is customary to eat twelve grapes as the clock strikes twelve, separating the outgoing year from the incoming year…" this means that at least in 1896 it was done, and probably many years before that for it to be considered “customary” by the local press.

The plausible explanation for why someone decided it was a good idea to get cold the last night of the year waiting for a clock to strike 12 strokes and choke on a dozen grapes goes back to 1882. That year the mayor of Madrid, José Abascal y Carredano, decided to impose a tax of 5 pesetas for all those who wanted to go out and celebrate the Three Kings on the night of January 5. The purpose of this was not to stop any tradition or start any new ones but to stop the general public from raising hell and getting drunk through the night – this should not be confused with the festive floats and processions which were in the afternoon and open to everyone.

However, it did deprive the vast majority of the locals of partying that night, except for those that were well off, of course. This obviously led to the people rebelling and trying to find a way to let off steam so New Year’s Eve became the night of preference for partying and an opportunity to make a mockery of the recent bourgeois traditions imported from France and Germany. The local newspapers frequently published how the upper class now celebrated the New Year by drinking champagne and eating grapes during the New Year’s Eve dinner, so as an act of protest the working class would congregate in the Puerta del Sol and eat grapes as the clock struck twelve.

This behaviour quickly spread and popularised in the capital, to the point that in 1897 the merchants of the city advertised the sale of “Lucky Grapes” and within just a few years it was known as far away as Tenerife. Now, this is when the Levante wine farmers come on the scene, taking advantage of their surplus production in 1909, they carried out a national campaign to embed and enhance the custom throughout the country and were thus able to sell all their harvest. This behaviour quickly spread and popularised in the capital, to the point that in 1897 the merchants of the city advertised the sale of “Lucky Grapes” and within just a few years it was known as far away as Tenerife. Now, this is when the Levante wine farmers come on the scene, taking advantage of their surplus production in 1909, they carried out a national campaign to embed and enhance the custom throughout the country and were thus able to sell all their harvest.

Clearly, it worked and today there are few who do not welcome the New Year with 12 grapes in their hand and eat them to the sound of each stroke as it counts down to the New Year. Rare is the Spaniard who will risk poisoning their fate for the coming year by skipping the grapes, many don’t finish them in time and it does take a bit of practice but it is the effort that counts, no effort – no luck, well at least that’s what those who don’t succeed tend to say…

For those who cannot be in the Puerta del Sol, they will follow it on television, normally on La Primera which tops the national audience ratings year after year with around 8 million viewers, some 6 million more than second place. Being such an important occasion some people spend a few extra minutes to remove the seeds or peel the skins off their grapes all in an attempt to improve their chances of swallowing them in time. My best piece of advice is: buy small seedless grapes and you’ll have no problem but they are not easy to come by as the traditional grape variety for New Year's Eve is the Vinalopó from the Valencian Community, the one promoted by the wine farmers back in 1909, so if you can't find seedless try to avoid the large juicy ones or you’ll be in trouble and may well choke your way into the New Year, try and pick the smaller ones and at least remove the seeds…. Good Luck and wishing you all a Happy New Year! the national audience ratings year after year with around 8 million viewers, some 6 million more than second place. Being such an important occasion some people spend a few extra minutes to remove the seeds or peel the skins off their grapes all in an attempt to improve their chances of swallowing them in time. My best piece of advice is: buy small seedless grapes and you’ll have no problem but they are not easy to come by as the traditional grape variety for New Year's Eve is the Vinalopó from the Valencian Community, the one promoted by the wine farmers back in 1909, so if you can't find seedless try to avoid the large juicy ones or you’ll be in trouble and may well choke your way into the New Year, try and pick the smaller ones and at least remove the seeds…. Good Luck and wishing you all a Happy New Year!

1

Like

Published at 8:10 AM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 8:10 AM Comments (0)

Spain's greatest inventor?

Friday, December 13, 2024

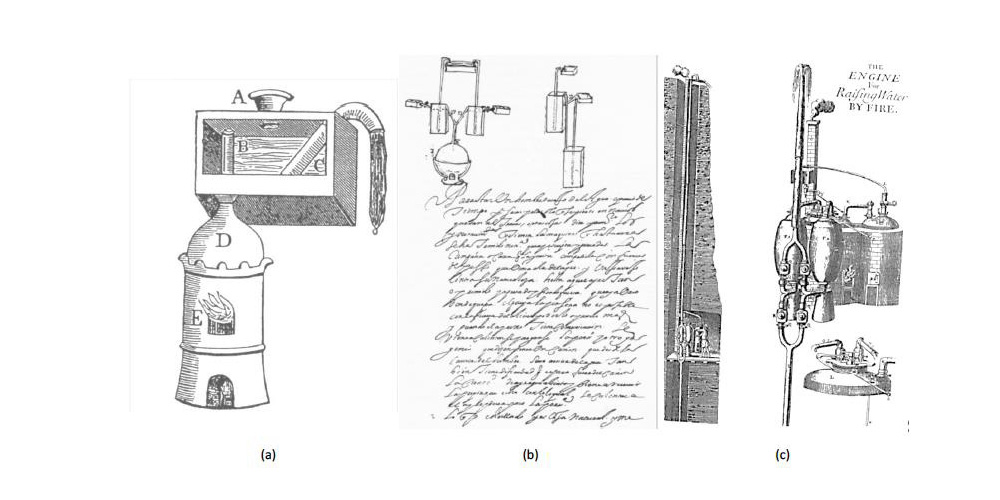

The Industrial Revolution changed everything. In the history of humanity, there have been many technological milestones and a good handful of them have contributed to shaping our world into what we know today. However, along with fire, writing and the digital revolution, the industrial revolution competes for first place in the ranking of importance and, therefore, its main representative: the steam engine. Perhaps that is why the Spanish find it so attractive to think that, perhaps, the person responsible for all this could be a Spaniard. A 16th-century Spaniard who designed a steam engine prior to the one that James Watt would patent in 1769. His name had been lost over the centuries as if brushed aside and forgotten.

Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont was a Navarrese military man, humanist and polymath who soon turned to music, cosmology and, of course, engineering. Depending on where we read about his life, we will find from modest biographies to true odes to this “Spanish Leonardo”. What is true, then? If we leave aside the ambiguous statements and the chauvinistic effluvia, we will find a series of interesting and commendable achievements, but that is far from the production of most of the historical figures that we have for "geniuses”, such as Da Vinci. And, knowing this, it is normal that we start from a certain point of mistrust when accepting that he could be the father of one of the most decisive revolutions in history. A suspicion that increases when we begin to document ourselves about it and find that there seem to be a few figures who dispute the invention of the steam engine. What's the problem? None of them lies as such, but it seems difficult to assign paternity to this invention and there is a good reason for it.

The truth is that the family tree of almost any technological revolution is very difficult to trace. It is not clear where it begins or who should be recognised as the father. In the end, a series of figures share quite important merits and it does not seem easy to choose one in particular, so our brain ends up asking us to desist, unable to unravel the web of contradictions that we find (especially in informative texts). Luckily, there are two key questions that we can ask ourselves whenever we find ourselves in this situation and that may help us resolve the doubt.

Of course, the simplest question would be "who was the first?". But in general, we will find that almost all devices are based on previous designs and, as much as it surprises us, they can be traced back almost as much as we want. For example, in the case of a machine that uses steam to generate movement, we could go back to the first century AD. and name Heron of Alexandria as the father of technology. His aeolipile was a sphere filled with water which, when heated, released pressurized steam through two twisted tubes, thereby spinning the sphere on an axis. In fact, maybe we could go back a few years because we know that Heron used to be inspired by previous designs by Ctesibius. However, we will agree that it was impossible to achieve the Industrial Revolution with the Alexandrian design. Therefore, the really important question is not that, but who put the intention and who made it efficient.

Heron did not know what to use the aeolipile for, his intention was not adequate and that is why he did not begin to use it to generate the workforce. That turning point, in which a technological anecdote finds a revolutionary application, is possibly the key to determining who its true inventor is. In this case, there is quite a bit of dispute, because until a few decades ago Thomas Savery was spoken of as the pioneer who developed, for the first time, a functional steam engine. Specifically, his purpose was to use it as a suction pump, capable of creating a vacuum by expanding and contracting steam. That happened in 1698 but we have already said that our Spanish candidate lived in the previous century, so if he had found a clear application, it could become the first practical application of which we are aware.

Well, the truth is yes. Indeed, Jerónimo had already used his steam engine to generate a vacuum and ventilate mines thanks to it. However, we will agree that none of these applications is close to the engines that made the Industrial Revolution what it was. However, there is an even bigger problem: it was completely inefficient, practically a curious toy, better than nothing, but quite useless. Thomas Newcomen would take a new step in 1712, creating the atmospheric steam engine, capable of pumping water more or less continuously, but it was still very inefficient. That is why we usually consider James Watt the father of the steam engine because when he came up with his patent in 1769, that machine had two basic characteristics: it was applicable and it was much more efficient than its predecessors. To get an idea, it consumed a third of the coal that Newcomen's needed to produce the same energy, and that is what we needed to fuel a true Industrial Revolution.

Without a doubt, Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont is a Spanish figure to be proud of, but despite the fact that he made some important progressions, it is difficult to justify that he is the father of a technology for which he was neither the first nor the one who gave the real leap in efficiency.

2

Like

Published at 10:57 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 10:57 PM Comments (0)

'El Día de los Santos Inocentes' and Its Somber Roots

Thursday, December 5, 2024

Día de los Santos Inocentes (Day of the Holy Innocents) is observed on December 28th in Spain and many Latin American countries, and its origin is rooted in a tragic event described in the Bible. According to the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 2:16-18), King Herod the Great, feeling threatened by the prophecy of the birth of Jesus, ordered the massacre of all male infants in Bethlehem who were two years old and under. This horrifying event .jpeg) is known as the "Massacre of the Innocents." is known as the "Massacre of the Innocents."

King Herod, having been informed by the Wise Men of the birth of a new "King of the Jews," sought to eliminate any potential challenger to his throne. When he realized that the Wise Men had outwitted him by not returning to disclose Jesus' location, he ordered the killing of all young male children in Bethlehem and its vicinity. This event caused untold suffering and grief among the families of these innocent children.

The Transformation of the Tradition

Over time, the commemoration of this somber event evolved into a cultural and social tradition with a distinctly different tone. In Medieval Spain, this day began to be marked by a series of pranks and practical jokes, akin to April Fool's Day in many Western countries. Today, Día de los Santos Inocentes is characterized by light-hearted antics and merriment. People play practical jokes, tell tall tales, and the media often publishes fake news stories, all in good fun.

The transformation from a day of mourning to one of mirth is an interesting cultural evolution. The exact reasons for this shift are not entirely clear, but it is believed that the blending of pagan and Christian traditions, along with a natural human tendency to ward off the darkness of winter with joy and laughter, played a significant role.

The Cultural Twist

Despite the comedic overtones associated with modern celebrations of Día de los Santos Inocentes, the day retains its historical and religious roots for many. It serves as a reminder of the innocent lives lost in Bethlehem and the cruelty of Herod's decree. In some regions, traditional observances still include religious services and prayers to honor the memory of the martyred children.

In various parts of Spain and Latin America, unique local customs also reflect the day’s dual nature. For example:

-

In Guatemala, the day is marked by the release of small lanterns into the sky, symbolizing the souls of the innocent children.

-

In Mexico, elaborate practical jokes are combined with a more reflective aspect, where families remember the biblical story.

-

In Ecuador, there are parades and street performances that mix comedy with poignant reminders of the historical events.

A Day of Duality

Día de los Santos Inocentes is a day of duality, blending sorrow with joy, and reflection with laughter. It demonstrates how cultural traditions can evolve and adapt over time, incorporating new elements while retaining their historical and religious significance. The pranks and jokes that are now synonymous with the day bring a sense of joy and community, but they also add a layer of complexity to the commemoration of an event that originally symbolized a dark period of infanticide and suffering.

In celebrating Día de los Santos Inocentes, many people are reminded of the resilience of the human spirit and the importance of finding light even in the darkest of times.

2

Like

Published at 2:48 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 2:48 PM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|