Wine vinegar probably came into use in the Iberian Peninsula at around the time when the Iberians were starting to trade with the Phoenicians. Vinegar-making most certianly dates back at least as far as the first Iberian-made wine.

Texts from the Roman period mention vinegar as a substance in habitual use, and some also report on its production and trade. Given that Hispania, and more specifically its constituent province of Baetica (present-day Andalusia), was the main supplier of wine to the Roman Empire, it seems likely to have supplied it with vinegar, too. The first written reference to this appears in the writings of Columella (4-70AD) in the 1st century.

Texts from the Roman period mention vinegar as a substance in habitual use, and some also report on its production and trade. Given that Hispania, and more specifically its constituent province of Baetica (present-day Andalusia), was the main supplier of wine to the Roman Empire, it seems likely to have supplied it with vinegar, too. The first written reference to this appears in the writings of Columella (4-70AD) in the 1st century.

The main Hispanic grape varieties came from the southern and eastern parts of the colony. One of the most prized was one that Pliny (61-112AD) refers to as balisca (though the Iberians called it coccolobis), of which there were two varieties, one that turned dry as it aged and another that became sweeter. There was also a red grape of lesser quality known as aminnea.

One of the best-known wines came from Turdetania (an area that occupied part of present-day Andalusia, including the Jerez area, in Cádiz). It was regarded as a luxury product and was sold in amphorae bearing the inscription vinum gaditanum (wine of Cádiz). Another famous one, mentioned by Pliny, was lauro: held to be one of the best wines in the world, it is thought to have originated in the Liria region, in present-day Valencia.

It makes sense to suppose that areas that produced wine of such quality, and in such quantity, would also have been sources of fine vinegar, though trade-related documents to prove this are few and far between. However, vinegar (acetum) was one of the most highly regarded condiments and preservatives in Roman cuisine and medicine.

A container of oil (lagoena) , a salt cellar (salinum) and a bottle of vinegar (acetabulum) were regarded as essentials in the home of a citizen of the Roman Empire. The custom survives to this day, and all restaurants in Spain have a receptacle holding different containers of vinegar, oil, salt and pepper at the disposal of customers for seasoning the food if they think it needs it.

Apicius’ cookery book mentions different categories of vinegar, designated according to their source or flavouring: for example, vinegar from Ethiopia, Syria and Libya; vinegar flavoured with cumin (cuminatum) , aniseed (anetatum), coriander (coriandratum) , and laserpicium (laseratum) .

Not all the different kinds of vinegar used in Roman cooking were wine-derived, however, one favourite was pear vinegar (mentioned in a recipe by Palladius (408-431? - 457/461?), and there were also marrow, bluebell, fig and other fruit vinegar.

In a pattern inherited from the Greeks, vinegar was still consumed in drinks, sauces and preserves. Oxymel, a mixture of vinegar and honey, was still drunk, and one particularly noteworthy sauce, known as oxigarum, was made by adding vinegar to garum; oxycrate, a mixture of water, honey and vinegar, was believed to be an effective treatment for gastric ailments; a mustard sauce (noted by Palladius) was composed of mustard seeds, honey, oil from Baetica and strong vinegar; and there were other sauces for fish, seafood and meat of various kinds.

The taste for acidic and sweet-and-sour flavours is clearly reflected in Apicius’ recipes: a third of them include vinegar or other acidulates among their ingredients. Vinegar was, of course, still used as a preservative, either in an acid solution in which foodstuffs were immersed, or for boiling some meats (such as duck and other fowl), and certain vegetables (such as helenium and bulbous vegetables).

One of the commonest uses for vinegar in the Roman Empire was as an additive to the water that soldiers drank in the absence of wine. It gave the water a bitter-sweet taste, and the acetic acid served as a disinfectant and kept it drinkable. The acidulated water drunk by Roman soldiers was that period’s equivalent of a soft drink and was known as posca, the word used for the liquid with which the compassionate soldier moistened the lips of Jesus on the cross as described in the New Testament (Mark: 15, 36).

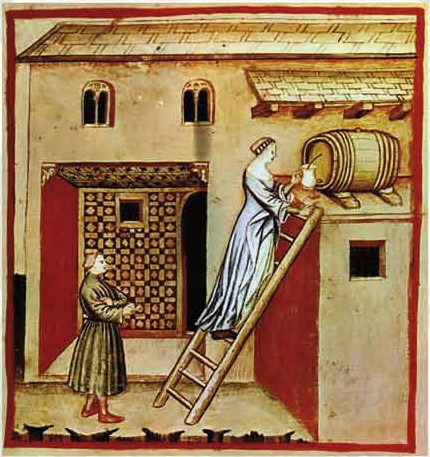

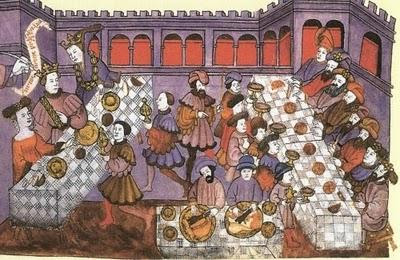

In Europe in the Middle Ages, the habits and customs of the Ancient World continued as far as vinegar was concerned: mixtures with honey (or other sweeteners) and vinegar (oxymel) were still made as sauces for meat and fish, as recipes of that period reflect. For example, the first known Spanish cookery book, the Libre del Sent Soví, written in Catalan in 1324, includes a recipe for a sauce to go with venison consisting of a mixture of “salt, vinegar, arrope [grape must boiled down to a thick concentrate, as sweet as honey] in regular proportions”. This common combination of flavours appears again in the (unknown) author’s advice in a recipe for lamb’s intestines: “Season with salt, bitterness and sweetness”. Oxigarum was still eaten, too, and furthermore, the taste for acidic flavours in cooking became accentuated - a phenomenon that is one of the principal distinguishing features of medieval cooking in Europe.

In Europe in the Middle Ages, the habits and customs of the Ancient World continued as far as vinegar was concerned: mixtures with honey (or other sweeteners) and vinegar (oxymel) were still made as sauces for meat and fish, as recipes of that period reflect. For example, the first known Spanish cookery book, the Libre del Sent Soví, written in Catalan in 1324, includes a recipe for a sauce to go with venison consisting of a mixture of “salt, vinegar, arrope [grape must boiled down to a thick concentrate, as sweet as honey] in regular proportions”. This common combination of flavours appears again in the (unknown) author’s advice in a recipe for lamb’s intestines: “Season with salt, bitterness and sweetness”. Oxigarum was still eaten, too, and furthermore, the taste for acidic flavours in cooking became accentuated - a phenomenon that is one of the principal distinguishing features of medieval cooking in Europe.

The Moors who invaded the Iberian Peninsula from 711 on were also fond of acidic flavors in their food: they used fruits such as acidic apples, bitter oranges, pomegranates and other tart fruit. Despite the Koran’s prohibition against drinking wine, some periods were more permissive than others in Muslim Spain and vine growing was never abandoned altogether. Great care was taken, too, of Jerezana grapes, which were famed for their fleshy fruit and were eaten both fresh and dried (as raisins).

The acid-tasting condiments most frequently used in Spanish cooking were grape-derived: verjuice (the juice of unripe grapes, the most acidic of the edible acids) and vinegar. Over-acidity in food was corrected with honey or, later, cane sugar. Vinegar was used for boiling olives, capers and various vegetables, for making sauces and for marinating meat and fish. The marinade consisted of a mixture of sour milk, vinegar and morrî, a type of garum made from the guts of various fish in Al Ándalus. It was also used straight in salads, which were dressed then as now, as encapsulated in today´s popular saying: “La ensalada bien lavada y salada, poco vinagre y muy aceitada” (Salad should be well washed and salted, with just a little vinegar and plenty of oil). Another traditional use for vinegar that was carried through to the medieval period was its therapeutic application: the importance of dietetics from the 14th century on reinstated vinegar as a purgative and digestive aid.

During the Modern Era in Europe, the medieval preference for flavors with an acidic edge waned slightly, yet mildly acidic elements remain a feature of half the recipes of the period. This enduring predilection for bitter-sweet flavors is still in evidence in post-1750 Colonial Spanish cookery, in which vinegar plays a part, mixed with cane sugar or added as a finishing touch to many dishes. Other traditional uses for vinegar start to be recorded in the dietetic recipe books known since the 16th century by the generic name of ‘libros de mermelada’ (marmalade books), which contain recipes for marmalades made with honey or cane sugar, preserves in vinegar, sauces, spiced wines, and soaps, perfumes and remedies. The reason for this interweaving is that, from the 16th to 18th centuries, cane sugar, honey and vinegar were regarded as dietary remedies. Vinegar was believed to open the pores, thereby helping to convey food to all parts of the body.

Vinegar was a traditionally home-made product that the big sherry companies started to produce (retaining artisan production methods) from the 18th century on. As a rule, winery owners segregated wines afflicted by picado (acetification) into separate cellars so as not to spoil those around it. Vinegar, though a necessity, was perceived as a black mark against a bodega rather than a contribution to its kudos. Therefore vinegar was usually only for domestic use, and it was not until the mid 20th C. that sherry vinegar was exported. Nonetheless, some of the big firms started to devote attention to it.

Vinegar was a traditionally home-made product that the big sherry companies started to produce (retaining artisan production methods) from the 18th century on. As a rule, winery owners segregated wines afflicted by picado (acetification) into separate cellars so as not to spoil those around it. Vinegar, though a necessity, was perceived as a black mark against a bodega rather than a contribution to its kudos. Therefore vinegar was usually only for domestic use, and it was not until the mid 20th C. that sherry vinegar was exported. Nonetheless, some of the big firms started to devote attention to it.

In the course of the 20th century, sherry vinegar developed into one of Spain’s three regulated Designations of Origin for vinegar. It is made by entirely artisan methods, which entitles it to 3% of residual alcohol and a minimum acidity of 7% by volume. This vinegar gradually acquires a dark mahogany color as it ages: it is made from grape varieties Palomino Fino, Palomino de Jerez (a variety that is becoming increasingly scarce), Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel (all of them whites). Only two types of vinegar are marketed: Vinagre de Jerez, which has been aged for a minimum of six months, and Vinagre de Jerez Reserva, aged for a minimum of two years, but generally much older than the stipulated minimum, sometimes as much as 50 years old, such as Gran Capirete.