The Industrial Revolution changed everything. In the history of humanity, there have been many technological milestones and a good handful of them have contributed to shaping our world into what we know today. However, along with fire, writing and the digital revolution, the industrial revolution competes for first place in the ranking of importance and, therefore, its main representative: the steam engine. Perhaps that is why the Spanish find it so attractive to think that, perhaps, the person responsible for all this could be a Spaniard. A 16th-century Spaniard who designed a steam engine prior to the one that James Watt would patent in 1769. His name had been lost over the centuries as if brushed aside and forgotten.

Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont was a Navarrese military man, humanist and polymath who soon turned to music, cosmology and, of course, engineering. Depending on where we read about his life, we will find from modest biographies to true odes to this “Spanish Leonardo”. What is true, then? If we leave aside the ambiguous statements and the chauvinistic effluvia, we will find a series of interesting and commendable achievements, but that is far from the production of most of the historical figures that we have for "geniuses”, such as Da Vinci. And, knowing this, it is normal that we start from a certain point of mistrust when accepting that he could be the father of one of the most decisive revolutions in history. A suspicion that increases when we begin to document ourselves about it and find that there seem to be a few figures who dispute the invention of the steam engine. What's the problem? None of them lies as such, but it seems difficult to assign paternity to this invention and there is a good reason for it.

The truth is that the family tree of almost any technological revolution is very difficult to trace. It is not clear where it begins or who should be recognised as the father. In the end, a series of figures share quite important merits and it does not seem easy to choose one in particular, so our brain ends up asking us to desist, unable to unravel the web of contradictions that we find (especially in informative texts). Luckily, there are two key questions that we can ask ourselves whenever we find ourselves in this situation and that may help us resolve the doubt.

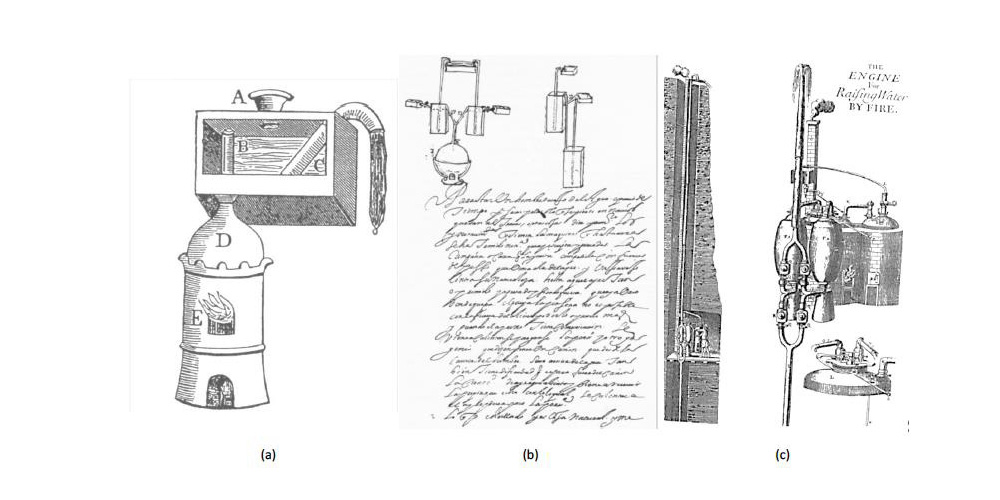

Of course, the simplest question would be "who was the first?". But in general, we will find that almost all devices are based on previous designs and, as much as it surprises us, they can be traced back almost as much as we want. For example, in the case of a machine that uses steam to generate movement, we could go back to the first century AD. and name Heron of Alexandria as the father of technology. His aeolipile was a sphere filled with water which, when heated, released pressurized steam through two twisted tubes, thereby spinning the sphere on an axis. In fact, maybe we could go back a few years because we know that Heron used to be inspired by previous designs by Ctesibius. However, we will agree that it was impossible to achieve the Industrial Revolution with the Alexandrian design. Therefore, the really important question is not that, but who put the intention and who made it efficient.

Heron did not know what to use the aeolipile for, his intention was not adequate and that is why he did not begin to use it to generate the workforce. That turning point, in which a technological anecdote finds a revolutionary application, is possibly the key to determining who its true inventor is. In this case, there is quite a bit of dispute, because until a few decades ago Thomas Savery was spoken of as the pioneer who developed, for the first time, a functional steam engine. Specifically, his purpose was to use it as a suction pump, capable of creating a vacuum by expanding and contracting steam. That happened in 1698 but we have already said that our Spanish candidate lived in the previous century, so if he had found a clear application, it could become the first practical application of which we are aware.

Well, the truth is yes. Indeed, Jerónimo had already used his steam engine to generate a vacuum and ventilate mines thanks to it. However, we will agree that none of these applications is close to the engines that made the Industrial Revolution what it was. However, there is an even bigger problem: it was completely inefficient, practically a curious toy, better than nothing, but quite useless. Thomas Newcomen would take a new step in 1712, creating the atmospheric steam engine, capable of pumping water more or less continuously, but it was still very inefficient. That is why we usually consider James Watt the father of the steam engine because when he came up with his patent in 1769, that machine had two basic characteristics: it was applicable and it was much more efficient than its predecessors. To get an idea, it consumed a third of the coal that Newcomen's needed to produce the same energy, and that is what we needed to fuel a true Industrial Revolution.

Without a doubt, Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont is a Spanish figure to be proud of, but despite the fact that he made some important progressions, it is difficult to justify that he is the father of a technology for which he was neither the first nor the one who gave the real leap in efficiency.