By the 31st of December Columbus had decided that he should load provisions and water aboard the Niña. He was still receiving promises of more gold from the Cacique, and he would have liked to explore more down the coast to find the source of the metal, but he wrote that he was wary of another accident that could make the Niña incapable of the return journey. He had met cordially with several native Caciques and had received gold as gifts, and he urged the men who were to remain behind at fort Navidad to obtain as much gold as they could for their return from Spain. It was during one of these meetings that a native from further along the coast to the east reported having seen the Pinta. This news added another dimension to Columbus' worries. There were now two expeditions; the one that he led, and the one led by Pinzón.

In order to give the natives a show of force, he took the king and some of his advisors out in the Niña and fired one of the lombards at the hull of the Santa Maria. They were suitably impressed when the ball went straight through the ship and a good way beyond. He writes that he hoped that the natives would see that his men were friends and would defend them in case of attack from a nearby tribe called the Caribs, who the natives feared.

He began to organise the provisions for those who were to remain. Most were volunteers. Along this coast Columbus’ small flotilla had seen nothing but good nature and friendship from the natives. He left Diego de Arana, a native of Cordoba and Pedro Gutierrez, "repostero de estrado" of the King and Rodrigo de Escovedo, a native of Segovia. He gave them all the powers which he had received from the sovereigns in Castile. The officials supplied by Isabel, the escribano and alguacil also elected to stay. He left them seeds for sowing and a ship's carpenter and calker, a good gunner “who knows a great deal about engines” and a cooper and a physician and a tailor, and all, he says, are seamen. He left them biscuit sufficient for a year and wine and much artillery and the ship's boat in order that they, as they were most of them sailors, could go to discover the mine of gold when they should see that the time was favourable.

Columbus left 39 men behind at La Villa de Navidad on the 22nd January 1493. He had no alternative to leaving good crewman behind whilst he was obliged to sail with people that he did not trust.

He first had to navigate seas to the east of Española (Haiti) which were full of reefs and sandbanks, and Columbus carefully picked his way through them. He sent a sailor to climb the rigging around the main mast and watch the sea ahead for dangers. It was in the afternoon of the 6th that the lookout called that he had seen the Pinta ahead. With nowhere safe to anchor, the two ships returned to the coast at a place they had called Monte Christi.

When they finally met Martin Alonso Pinzon, the captain of the Pinta, he was full of apologies saying that he was forced by circumstances beyond his control to leave the other ships behind. The natives on his ship had led him on a wild-goose-chase from island to island looking for gold. Columbus wrote that he believed none of it, and another account says:

“(they) had not obeyed and did not obey his commands, but rather had done and said many unmerited things in opposition to him, and as Martin Alonso had left him from November 21st to January 6th without cause or reason but from disobedience: and all this the Admiral had suffered in silence, in order to finish his voyage successfully” The account continues, “he decided to return with the greatest possible haste and not stop longer.”

On the 9th, whilst they were anchored in the mouth of a river at Monte Christi, Columbus ordered the ships to sail upriver to fill the water butts on both ships with fresh water for the voyage home. While they were filling the water butts, his sailors were amazed to see that the sand of the river was full of grains of gold. When they brought the barrels aboard they found that the gaps between the staves and the hoops were full of gold dust. He had found the source of the gold just 20 leagues from La Villa de Navidad, but the crews both ships now knew where it was, and the stakes in this great gamble had just got higher. Columbus writes:

“That he would not take the said sand which contained so much gold, since their Highnesses had it all in their possession and at the door of their village of La Navidad; but that he wished to come at full speed to bring them the news, and to rid himself of the bad company which he had, and that he had always said they were a disobedient people.”

Around 12th January, they left the coast behind and struck out across the Atlantic. The two ships stayed in formation for four weeks making poor headway, but on 13th February ran into a storm. For three hours the two ships tried to hold their easterly course, but finally they had to turn and run west before the force of the gale. During the night, the ships became separated and the Niña spent the rest of the next day going west. The Niña was not handling well in the storm because the ballast of the ship was wrong, and Columbus ordered the crew to fill the empty drinking-water and provision barrels in the hold with sea water to try and stabilise the ship.

At the height of the storm Columbus called the crew to prayer and he ordered as many dried peas as there were crewmen to be brought from the provisions. He marked one with a knife and put them all in a hat. They drew lots four times and he made the crew vow that if they survived the voyage whoever picked the marked peas would make the pilgrimages to four different shrines in Spain and that the first land they would all go in procession in their shirts to pray under the invocation of Our Lady. In secret, he wrote a declaraion about all that he had discovered and wrapped it in a wax cloth with a letter asking whoever found it to return it to the King and Queen of España so that: “The Sovereigns might have information about his voyage.” He ordered that a barrel be brought to his cabin and he sealed the parcel within and threw it overboard.

On the morning of the 15th February the skies brightened from the west and they saw an island on the horizon. It took them all day to reach it, but they could find no harbour and so they dropped anchor on the lee side of the island. In the night the anchor was torn away, and the Niña had to beat about to hold position. The following morning they dropped a second anchor and sent the small boat ashore where his sailors learned it was the island of Santa Maria, one of the islands of the Azores. That evening, Juan de Castaneda, the governor of the island, sent men to the beach with fowls and fresh bread. Castaneda apologised for not coming himself, but that in the morning he would bring more refreshments. In thanks for their deliverance from the storm, Columbus allowed half the crew to go ashore and fulfil the vows they made. They asked the islanders there to send a priest to say mass for them in a small hermitage further along the coast.

Columbus had forgotten that the King of Portugal had put a price on his head before the voyage, but now they had returned safely after discovering a New World, there was a bigger price offered for their capture and the safe delivery of the knowledge they carried in their heads; and the Azores were Portuguese territory.

Whilst the crew prayed they were surrounded by armed villagers. Columbus waited for them to return, then fearing the worst, he sailed around the coast to where he could see the hermitage. The governor of the island was there with armed soldiers and he was rowed out to the Niña in the small boat. Columbus tried to entice them aboard, but the governor was too wily to be captured. Even with half of them held on the island, the Niña still had had sufficient crew to continue her return voyage to Spain. He held up the letters from Isabel and Ferdinand and promised retribution against Portugal from España unless his men were returned. The governor yelled that he did not recognise the kingdom of España; he was duty bound to follow the orders of the King of Portugal.

Columbus realised that he was wasting his time, and since the wind was against him he ordered that running repairs be made to the ship which was taking on water. He had already lost one anchor and was not about to lose any more either to sabotage or storm. The weather was worsening and he set sail for the nearby island of San Miguel, but the seas became so rough that he was forced to return to Santa Maria. On the 22nd they anchored in the lee of the island and a messenger asked if Columbus would allow two priests and an escribano (notary) aboard to examine his papers of authority. They were allowed aboard and given every respect as they studied the letters signed by Isabel and Ferdinand. Finally, after conferring in whispers, they told Columbus that his men would be returned. Columbus had successfully called the governor's bluff, and his men rowed out to take their place on the Niña once more.

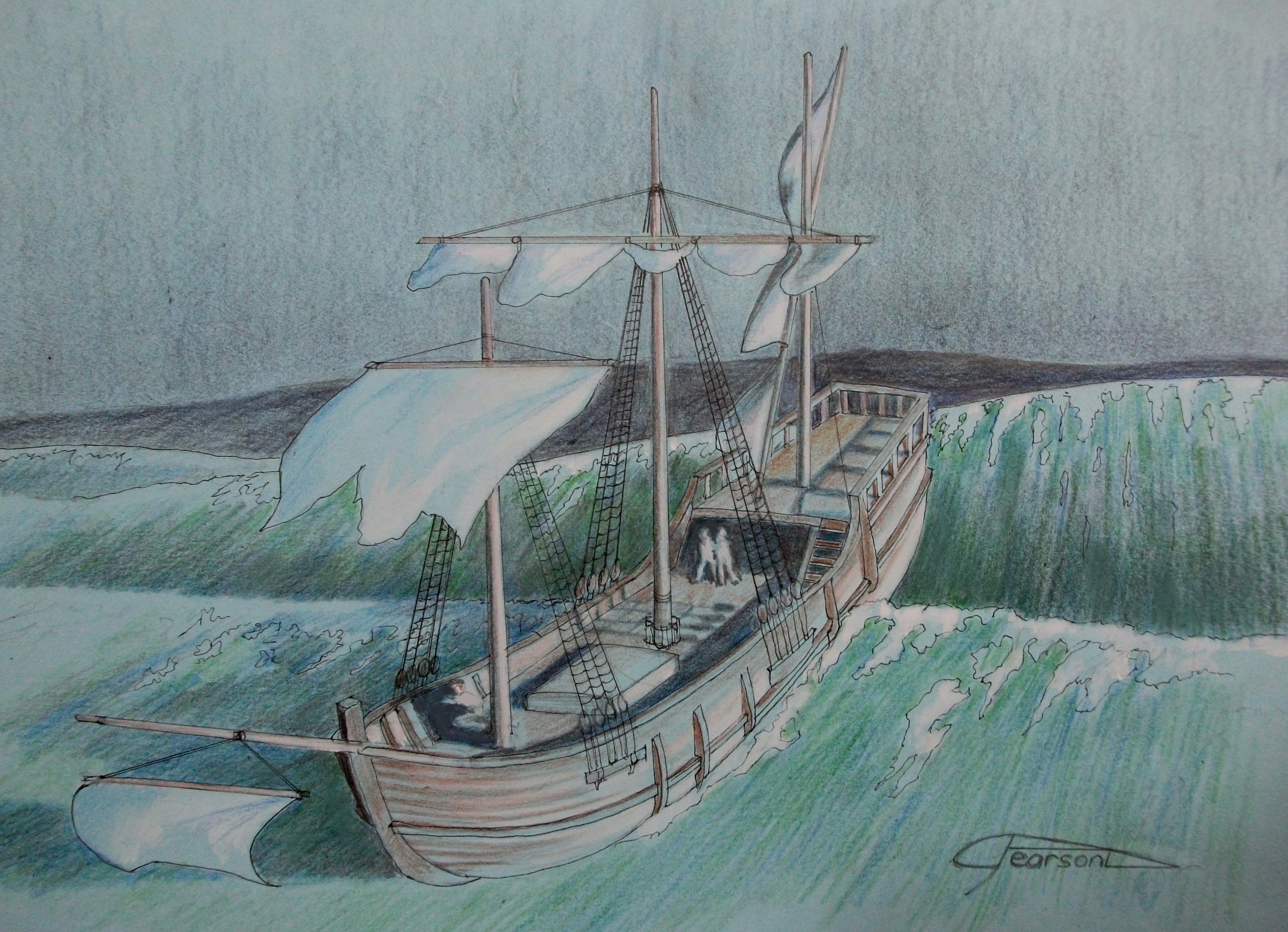

Picture; Alan Pearson, alanpearson.pixels.com

On Sunday 24th February the wind eased and came around to a direction which would take the Niña back to Spain. Columbus immediately put on all sail and left the Azores behind. All went well for three days before what could have been a tornado battered the tiny ship and split her sails. By March 4th the storm still had not abated, but the dawn brought the sight of land and many of his sailors recognised the Rock of Cintra to the north of the port of Lisbon. At the mouth of the river Tagus was the small village of Cascaes, and the villagers had watched the Niña’s approach through the storm and had gone to the church and prayed for the safe return of this tiny vessel. Their prayers were answered, and Columbus docked his ship at Rastelo within the bay of Lisbon, where he learned that 25 ships had been lost in the storm, and many more had been tied-up in Lisbon waiting for the storm to pass. There was no news at all of the Pinta.

But the storm was not over for Columbus. He was still in hostile Portugal, and the flagship of the Portuguese navy was also tied up in Rastelo waiting for the storm to pass. Columbus noted that; “She was better furnished with artillery and arms than any ship he ever saw.” On March 5th her captain and financial patron, Bartholomew Diaz, sent an armed party to the Niña to demand that Columbus come to his ship and give an account of himself. Columbus wisely refused. The reply came back that he could send the master of the Niña in his stead. Columbus again refused. No member of his crew would leave his ship to be held hostage.

Realising that he was on a knife edge, where any aggression would result in a war with España, Diaz asked to see the letters of free passage given by Isabel and Ferdinand. Columbus agreed, and after reading the letters he sent his captain, Alvaro Dama, who arrived, “In great state with kettle-drums and trumpets and pipes” and put himself and his crew at the disposal of the admiral. All of Lisbon had heard of the discovery and wanted to see Columbus and the natives of the Indies, and for the next three days they were inundated with visitors and dignitaries. He was invited to visit the King of Portugal who was at the valley of Paraiso, nine leagues from Lisbon and he was entertained and recieved “many honours and favours”.

Finally, at 8 o'clock on March 13th Columbus raised the anchors and set sail to return to España. Two days later at sunrise he was off the sandbar at Saltes, Huelva, and when the tide turned at mid-day, he sailed upriver and tied up the Niña at the same dock that she had left on August 3rd the year before.

Pinzón and the Pinta had missed the Azores and arrived at the port of Bayona in northern Spain. After a stop to repair the damaged ship, the Pinta limped into Palos just hours after the Niña. Pinzón had expected to be proclaimed a hero, but the honour had already been given to Columbus. Pinzón died a few days later.