On July 17 1936, 34 year-old Captain Virgilio Leret of the Spanish Air Force was relaxing with his wife, Carlota Leret O’Neill, and his two daughters, Maria Gabriela and Carlota. He had rented a yacht and anchored it just off the Atalayón Hydroplane base in Melilla in North Africa, where he had been posted as base commander. The yacht was an ideal place to escape the July heat of the African coast and his family had joined him for a short holiday. This was the summer holiday season when the Spanish flocked to the coasts. This yearly exodus to escape the heat was called to verano. The base was deserted with nearly all the aircrews and maintenance men on holiday with their families. Leret had few urgent duties at the base, and it was ideal for him to row out to the yacht to be with his family when he was not busy.

Vigilio Leret

Vigilio Leret

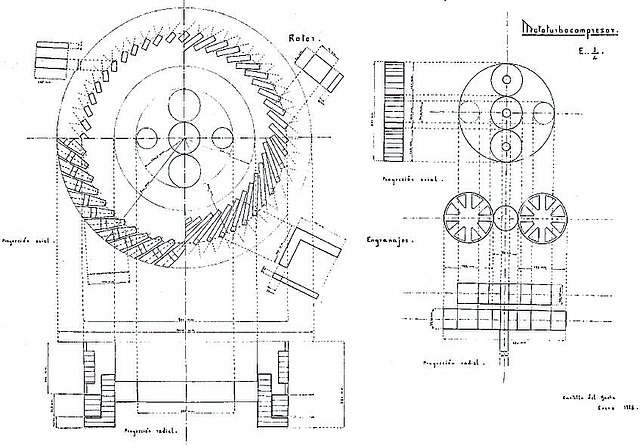

Leret was an exceptionally gifted engineer and was about to begin the production of an invention that he had been working on for the last few years. The year before, he had patented the design of “The turbo compressor continuous combustion engine como propulsor de aviones, y en general de todo clase de vehículos.” No less a dignitary than the Prime Minister of the Republic, Manuel Azaña, was about to order that production of the new motor would commence in September 1936 at the Hispano Suiza de Aviación engineering works. Three months earlier, on April 29, Azaña had made him professor of the mechanics’ school at Cuatro Vientos airfield near to Madrid. He had already been given his posting to El Atalyón , but had stayed on at Cuatro Vientos until May. Leret was killing time before he became a consultant in the manufacture of his jet engine.

(Sir Frank Whittle was the first to patent the jet engine in 1930,then Leret’s design was patented in 1935, with the German physicist Hans Von Ohain coming last when he patented his version of the jet engine in 1936.)

The Leret turbocompressor.

Leret’s career in the air force had not been without complications. He had followed in his father’s footsteps and joined an army academy at 15 years-old. He graduated top of his class in 1920 as a Second Lieutenant. One of his first postings in May 1921 was to the Campamento de Aviasión de Sania Ramel, the first airport in Spanish Morocco. This was to be his introduction to aviation.

After this he spent time in various infantry divisions in mainland Spain and it was during one of these tours that he met the woman who would become his wife, Carlota O’Neill y de Lamo, who was working as a left-wing writer. He had already tried to take the army’s military pilot course, but he had been unable to complete it because of other duties. In March 1926 he was at Los Alcalázares where he started training as an observer. This was also interrupted by first an air accident that hospitalised him for month and then malaria that took him three months to recover from. A year later, in October 1927, he qualified as a civilian pilot and the following January he completed his military pilot training.

In November 1928 he wrote to Carlota asking if she would marry him “as a social defence for the future”. She had already given him two daughters, and it was at his father’s request that he had proposed. On February 10 1929 he married Carlota, but Virgilio’s staunchly Catholic family ignored his children because they had been conceived out of wedlock. Nevertheless, Leret continued with his studies and in 1929 he qualified as an electromechanical engineer after completing a correspondence course.

However, storm clouds were gathering over Spain, and the military was becoming a hotbed for dissent. Some of this was over pay and the lack of promotion prospects, and many of the career officers were actively supporting dissent.

On December 15, 1930, Leret and some of his fellow officers refused to pursue General Queipo de Llano and Air Commander Ramón Franco who had escaped by air after a failed military uprising at the Cuatro Vientos airbase. This came three days after the Jaca uprising. His superiors sentenced him and eleven others to prison and discharged them from the army. Things moved quickly, and within three months the Second Spanish Republic had been proclaimed. Leret and his comrades were released and restored to their previous rank and pay in the army.

In May 1932 Leret took the seaplane course at Melilla which he completed in February 1933. He was in trouble again when he publicly denounced a political military broadcast and was sentenced to two months’ imprisonment in the fortress of El Hacho, Ceuta. It was whilst he was in prison that he finalised the design of his jet engine.

His troubles were all behind him now and he was enjoying the swimming, fishing, late dinners and long siestas with his family on the yacht. Their holiday continued for two weeks until Friday July 17, when at midday they heard gunfire at the base. Shortly after, Armando González Corral and Luis Calvo Calavia, two of his fellow officers at the base, rowed a boat out to the yacht and told him that the base was under attack from the Nationalists. Leret picked up his gun and hat and kissed his wife before joining the other men in the boat. As they rowed away, Carlota watched the face of her husband, who never took his eyes off of her. She never saw him again.

At the base Leret discovered that a column of Regulares led by the Francoist Moroccan officer Moham Meziane were advancing on Melilla and had stopped to take the airbase. Hopelessly outnumbered and with little ammunition, Leret defended the base for around two hours until the ammunition ran out. They surrendered, and the Regulares severely beat Leret and his men and threw them in prison. The following morning they were taken out and shot. One report states that his own officers were forced to shoot Leret. They were the first casualties of the Spanish Civil War.

Carlota knew nothing of events until the Moroccans came to the yacht and took her ashore the same morning that her husband was killed. Five days later, she was officially arrested as a suspected “red” and thrown into prison. Carlota was handed four suitcases that had been on the yacht. The Moroccans had been lax and had not searched the cases assuming that they contained only clothes; but one of them contained three sets of plans for Virgilio’s jet engine. She was not told what fate had befallen her daughters.

Afraid that the plans would fall into the hands of the Francoists, Carlota made plans to smuggle them out of the prison. One of the other inmates was Ana Vásquez, who had been put in prison for prostituting her own daughters. Ana was not suspected of any political involvements, so was told to keep an eye on the “reds” and inform on them. Instead, Ana helped Carlota smuggle the drawings out wrapped in dirty laundry. The drawings were collected on the outside by the son of another inmate whose mother had been imprisoned after her husband had been shot. He hid them under a loose floor tile in his house.

Carlota was tried three times by a military court and sentenced to six years in prison. The Spanish Civil War raged on, and at one point when the Falangists had taken Toledo, a group of soldiers came to the prison and demanded some women to shoot in celebration. Carla hid in a water tank with just her nose out of water. She remained there all night and only came out when the Falangists had gone.

She was released in 1941 and immediately went to the now deserted house where the plans had been hidden. After a short search through sand and rubble she found the loose tile and the drawings beneath. The dry desert air had preserved them in near pristine condition.

The Spanish Civil war was over, with the Caudillo brutally ruling over a starving, impoverished and demoralised Spain. Outside of the “allegedly” neutral Spain, the Second World War was escalating in ferocity, with Hitler invading Russia in June 1941 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December. If ever the free world needed a secret weapon it was now.

Carlota could not possibly have known about the top secret work on jet engines of Frank Whittle or Hans Von Ohain. She only knew that her husband’s plans must not fall into German hands. Carlota had found one of her daughters by now, and they both took one set of the plans to the British Embassy where they met James Dickson the aviation attaché.

She gave Dickson the plans, but he was killed in an accident shortly after they met. Carlota never found out what happened to the drawings that she gave him. Over the next few years, Carlota made contact with her other daughter, but wherever she went she took the remaining drawings with her.

Carlota Leret O’Neill finally settled in Caracas, Venezuela, as an exile with her daughters. She died in 2000 at the age of 90. Her youngest daughter, Carlota, began to show her father’s drawings in an effort to draw attention to his work. In 2011 Spain’s AENA’s national airport authority financed a documentary on Spanish television about Leret’s work. Later, Carlota took the drawings to the Museo del Aire in Madrid. They were impressed, but lacked the funding to mount a display of her father’s engine.

“They were excited at the museum but they told me they didn’t have the money to build and mount the engine”. Carlota toured engineer’s workshops and finally ordered the building of a replica of the engine. This was paid for with her own money, and she won’t reveal how much it cost, although some of the money was raised from the sale of her mother’s memoirs.

The Turbo Compressor engine took 2,500 man-hours to build and comprised of 2,674 parts. In the Ministry of Defence’s 2002 publication, Aeroplano, aeronautical engineer Martin Cuesta wrote, “Had he not been shot his engine would surely have become a reality with the resulting honour for its creator and for Spain.”

Three hundred and ninety pages long, Carlota O’Neill’s book, Una Mujer En La Guerra De Espana, is a heart-rending story of poverty, prison and exile which is, above all, long declaration of her love for her husband, who was probably the first victim of the Spanish Civil War. His body was never found and there are no records of his grave.

Sources: Most of this story was taken from El Pais and Wikipedia. Carlota O’Neil’s books are on sale from Amazon.