After news of the first two voyages of Christopher Columbus had become widespread, every maritime nation throughout Europe scrambled for a slice of the action. They would chiefly be funded, sometimes with an unlimited budget, by King John II, and his successor Manuel I of Portugal, Henry VII of England and Isabel and Ferdinand of España. The widespread publication of his letters describing the islands that he had discovered galvanised maritime adventurers across Europe, and exploration was to become the game of the century.

When Columbus set sail on his second voyage in 1493, Juan de la Cosa accompanied him, but again, he is barely mentioned. (The log for the second voyage has never been found.) However, he appears in official records when he claims compensation for the loss of his ship, the Santa Maria. In a letter to de la Cosa, the king and queen give him praise and recompense for his ship.

“Salutations and thanks to you Juan de la Cosa … you have given us good service and we hope that you will help us from now on. In our service at our mandate you sailed as captain of a nao of yours … during which the lands and islands of the Indies were discovered, you lost your nao … In payment and satisfaction we hereby give you license and faculty to take from the city of Jerez de la Frontera, or from any other city or town or province of Andalusia, two hundred cahises of wheat to be loaded and carried from Andalusia to our province of Guipúzcoa, and to our county and the lordship of Vizcaya, and not elsewhere.”

This indicates that Juan de la Cosa was a trader as well as an explorer and cartographer. It also hints that he owned at least one other ship. In any case, the letter arrived too late; he had already set off with Columbus on his second voyage when it arrived, but even though he had been side-lined in the Columbus logs, he was fast becoming a significant player in the exploration of the New World.

When the third voyage sailed, it would be documented by Bartolomé de Las Casas, and its objective was to prove or disprove a claim made by King John II of Portugal, who had proposed that there was a much larger mainland to the south-west of the islands that Columbus had discovered. The king’s theory was based on reports that “canoes had been found which set out from the coast of West Africa (Cape Verde Islands) and sailed to the west with merchandise.” The travellers’ tales that had been dismissed as fables by previous mariners were now being examined more closely. Columbus left with six ships from Sanlúcar de Barrameda on 30 May 1498, but his search for a mainland had already been anticipated by another native of Genoa.

A replica of the Matthew in Bristol, England. Photo: Chris McKenna.

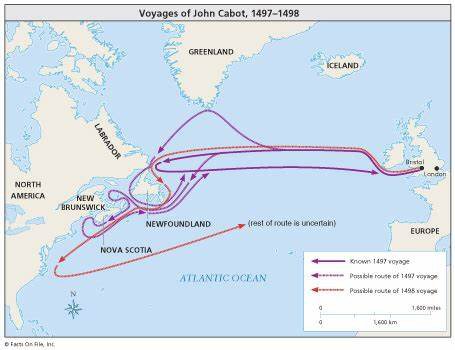

In May 1497 John Cabot had set off from Bristol with a crew of 18 in a boat named Matthew which was little larger than a fishing smack. Cabot had been born in Genoa, but had settled in England and had made several voyages out into the Atlantic searching for islands to use as staging posts to extend his exploration further west. When the news came of Columbus’ first voyage and discovery, he provisioned his ship and sailed due west from England. On June 24 he landed at what he thought was an island off north-east Asia, but was almost certainly Cape Bretton Island, at the entrance to the St. Lawrence Seaway, gateway to the great lakes of North America. On his return to England in August 1497 King Henry VII awarded him a pension of £20 and a prize of £10.

Whilst Cabot was away, a Portuguese navigator had sailed from Iceland to Greenland, which he supposed to be the extreme north-east of Asia. Cabot learned of this, and now infused with confidence after his success, decided to try this more northerly route. With the backing of the king, he set sail with two ships whose combined crews amounted to 300 sailors. They sailed in May 1498 (more or less the same time that Columbus sailed.)reaching Greenland in June and continued north until icebergs and a mutinous crew made Cabot turn south. He sailed offshore of Baffin Island, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and New England on his way south. Cabot found no signs of an Asian civilisation, and watching his dwindling supplies, decided to return to England. He reported his finds to the king when he arrived in the autumn, but Cabot died shortly after his return. King Henry, however, realised the significance of the discovery, and later claimed the whole of North America as an English possession.

All of these mariners were sailing into the unknown. The birthplace of sailing, the Mediterranean Sea, can generate fierce storms, but they pale into insignificance in comparison to the North-Atlantic. Columbus had discovered dozens of islands in the Atlantic, but that was all they were; islands. Cabot had discovered a mainland, but he had no idea how big it was. For his third voyage, Columbus now had a mission to find out if there was a bigger landmass further south-west.

Three of Columbus’ six ships were taking much-needed supplies to La Isabela on Hispaniola, and they sailed directly there. The remainder of Columbus’ fleet sailed to Porto Santo first and then to Madeira, where he spent time comparing notes with the Portuguese captain João Gonçalves da Camara. Finally, they sailed to the Cape Verde islands via the Canaries and took on supplies before setting out across the Atlantic.

Despite seeking all the advice that he could gather on the southern Atlantic, his fleet ran straight into one of its perils. On the 13 July his ships became becalmed in the doldrums. They were not far from the equator, and the sun beat down on the hapless ships, making working on deck during the day impossible. More dangerous, the above water timbers dried out and shrank, loosening joints and leaving gaps in the planking. Barrels of provisions suffered the same fate, and the contents of ones that were open began to putrefy. The dehydration of the crew meant that the consumption of precious fresh water accelerated to critical levels. Mercifully, an easterly wind finally arrived to push them out of the inferno.

On July 31 they sighted the island of Trinidad and sailed to its most south-western point, where they met with natives in canoes who had come from the west. The fleet sailed west and on 1 August arrived at the delta of the Orinoco River. Columbus realised that the delta was sure proof of a huge river system further west; he had found the southern continent. They entered a tidal race now called the serpent’s mouth into the Gulf of Paria, a bay enclosed by Trinidad to the east and South America to the west, and on the following day they landed on the west coast of Trinidad where they met stiff resistance from the natives and were forced to return to their ships to escape the attack. This was not the end of his trials, because early in the morning of August 4, the fleet narrowly missed another disaster when a tsunami swept into the bay and almost capsized the flagship.

For seven years Columbus had been the acclaimed discoverer of the Indies. He had been at the centre of a social, political and maritime revolution. He had suffered betrayals and hostility from his crews and challenges to his authority. In all of his voyages of discovery he had led from the front, through storms at sea and political intrigues at home, he had carried the flag of España, and it was this flag that was planted at the northern end of the bay on the Paria Peninsula to claim South America for España.

But Columbus did not go ashore. During the previous month he had been suffering from insomnia. It may have been caused by the constant stress of command and the ever present danger. His eyes had become bloodshot and he had difficulty seeing. The other captains planted the flag, erected a cross and read the speeches. Sometime later he went ashore in his official capacity to claim the find, but his health was now uncertain. At least the natives here were friendlier and gave him food, and he topped up his barrels with fresh water.

They returned to Hispaniola to find that there was a full scale rebellion going on amongst the Spanish settlers who had been promised rich farmlands and gold. Some of them had taken passages on returning supply ships and were now lobbying the king and queen, claiming that they had been misled and that Columbus was guilty of gross mismanagement. He hung some of his crew for disobedience and faced criticism from the church, which was disappointed that none of the natives had been converted to Christianity. In fact, Columbus was making quite a lot of money shipping them back to Spain and selling them as slaves. Finally cornered, Columbus had to agree to humiliating terms and he was removed as governor. He was arrested and put in manacles for transportation back to España where he would face the charges against him. When they ordered his crew to fasten the iron bands around his wrists they refused. None of the other captains or their crews would shackle him, and it was left to his ship’s cook who very reluctantly put him in chains. Even then, it was only because of Columbus’ insistence that the cook did what nobody else was prepared to do.

The exploitation of the natives continued unabated, and so did the exploration of the oceans. The next three years saw an explosion of voyages as the seagoing countries of Europe mounted expedition after expedition and the map makers struggled to keep track of the discoveries. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel of España had the lion’s share of the discoveries, but England and Portugal were about to claim some of the new lands and the huge profits that they would bring.