Written history is mostly composed of the names of kings and queens and the wars that they got themselves into. Peppered with dates of their births and deaths, they lie silently on the pages of history books like gravestones in a cemetery. But every so often, the whole world is changed forever by a monarch whose strength and spirit transcends the dust of time. Queen Isabel of Castile was one such monarch. Before her marriage to Ferdinand of Aragon, Hispaña was a disjointed union of often warring kingdoms. Powerful ducal family dynasties really controlled the power of the kings, and in turn, the kings and dukes all bowed to the pope and the Catholic Church.

Her path to the crown of Castile was itself a testament to the courage and resilience of Isabel. Her story begins when her father, King Juan II, was king of Castile. He was crowned in 1406 and he and his first wife, Maria de Aragon, produced four children before she died in 1445, but the only one to survive was a boy called Enrique.

King Enrique of Castile

King Enrique of Castile

Enrique grew to manhood and was married to Blanca de Navarra, but after seven years, the marriage was still unconsummated, earning Enrique the unofficial title of “El Impotente.” This left his 42 year-old father with a problem. His close advisor and friend, Álvero de Luna, suggested that he remarry, and proposed 19 year-old Isabella of Portugal as a likely candidate to produce another male heir. They were married in July 22 1447, and Isabella duly gave birth to two children with King Juan, a girl, Isabel, and Alfonso, a boy. Had her step-brother, Enrique, produced a male heir, then Isabel would never have been born.

This is where the plotting began.

Before the ink was dry on the marriage documents, Álvero de Luna began to dominate the new queen and her husband, even to the point of trying to control their marital couplings. The young Isabella railed at this interference, and tried to convince King Juan to get rid of his closest and most-trusted advisor. During her confinement, there were bouts of sickness, and Isabella suspected that the evil Álvero was trying to poison her. On 22 April 1451, she gave birth to a daughter whom they named Isabel, but she knew she must find a way to eliminate the threat that Álvero de Luna posed to her and the life of her daughter.

Several years after Isabel and Juan’s wedding, De Luna made a fatal mistake. One of the nobles had openly defied him, and Álvero had him thrown from a high window to his death. Isabella badgered her husband to have him arrested for murder, and when the witnesses described what had happened, King Juan had no alternative but to order Álvero de Luna’s execution. With the threat to her life removed, Isabella faced a new problem as the health of her husband slowly deteriorated. She gave him a son, Alfonso, in November 1453, but by the following July, Juan was dead.

Enrique had seen the writing on the wall and petitioned the pope to annul the marriage with Blanca de Navarra. (Blanca was entirely happy with the annulment and went on to have two children with her next husband). He now needed a new wife and a son. He was crowned King of Castile in 1454, and the following year he was married to Joanna of Portugal. In 1462, they had a baby girl, (eight years after the wedding!) whom they named Joanna. Unfortunately, the noble families of Castile were highly suspicious of Enrique, and even more suspicious of his drinking partner and friend, Beltrán de la Cueva, who had been seen slipping into Joanna’s room so often that the whole court knew of the affair, and the rumour grew that Enrique was not the father of the girl.

Princess of Asturias is a title usually given to the heir to the Spanish crown. And when Enrique invited the nobles to come to the palace and swear allegiance to little Joanna, the new Princess of Asturias, they grudgingly obliged, but gave her the unflattering name of Beltraneja; a name that has stuck with her throughout Spanish history. The disquiet festered amongst the nobles, who finally persuaded him to grudgingly name his half-brother Alfonso as heir. Enrique had been led into a trap. The following year, the same nobles proclaimed11 year-old Alfonso as king, and Enrique had to fight to keep his crown.

Civil war broke out amongst the nobles, who were split into factions about who should rule Castile. Enrique was weak and was ruled by his advisors who were disliked by many of the populace as well as the nobles. Isabel was 13 by now and of marriageable age, and Enrique tried to use her as a pawn to placate the wayward nobles. He was advised to marry Isabel to Pedro Girón Acuña Pacheco, Master of the Order of Calatrava and brother to the King's favourite, Juan Pacheco. These were two of the most evil men in the kingdom, and Pedro was known as a drunken violent lout. Badgered by his nobles, and desperately short on money, he agreed. The lure was that Pedro, who was very rich, would pay into the impoverished royal treasury an enormous sum of money.

Isabel was aghast and prayed to God that the marriage would not come to pass. Her prayers were answered when Don Pedro suddenly fell ill and died while on his way to meet his fiancée. The civil war began anew and went on for another three years. Whilst the war raged on, young Alfonso died of unknown causes. Isabel had powerful, ruthless and devious followers amongst the nobles, and she realised that poisoning and murder might be a part of their strategy, even to the extent of killing her own brother. Now there were only two choices for who would inherit the crown after Enrique; Joanna or Isabel.

The Toros de Guisando in Avila. Prehistoric sculptures that may have predated the Romans.

Isabel was front and centre in the battle to win the crown of Castile. Isabel had enough followers to defend her claim to the crown, and the dispute broke into open civil war again. Finally, Isabel and Enrique met at the Toros de Guisando in Ávila on 18 September 1468 and negotiated a truce which included agreeing to name Isabel as heiress to the throne and give her the title of Princess of Asturias. Many of the nobles wanted to have Isabel crowned immediately, but Isabel refused to be queen whilst Enrique was still alive. Enrique was still king, but only in name.

This was where the church became involved. The bishops called into doubt the validity of Enrique’s daughter Juana's lineage, and he desperately sought to marry her back into a royal family to regain her title. Meanwhile, Isabel had made herself the hottest, yet most dangerous woman in a boiling political stew of conflicting loyalties and alliances. Enrique and his nobles tried to marry her off in power deals with other kings, but she evaded all attempts at an arranged marriage and despite pressure from the nobles, she steadfastly refused to take the crown from her half-brother before he was dead.

The brother of the King of France and the King of Portugal paraded themselves before her, but she remained unmoved by them. The only candidate that Isabel had any interest in was the son of the King of Aragon. He had originally been betrothed to Isabel, but had been brushed aside by events. Aragon had just fought a war with France, and Isabel marrying into French royalty would be a disaster for the kingdom. The only problem was that Isabel and Ferdinand were second cousins, and the Church forbade their union because of the danger of inbreeding. Nevertheless, her advisors began negotiations for the wedding. Enrique had depleted the coffers of Castile with constant wars, and the main reason he was forced to sign the peace treaty of Guisando was a lack of money to continue fighting. Enrique tried to raise an army to contest the wedding, but found that his impoverished nobles refused to fund another war. Andalusia withdrew financial and military support making him virtually powerless to stop the wedding.

The secret wedding negotiations were not going well. To Ferdinand's dismay, Isabel was implacable about relinquishing her claim to the crown of Castile and she stipulated that the pre-nuptial agreement gave them equal power to rule over the kingdom. The deal was called “tanto monter, monter tanto” meaning that whoever rules, it comes out the same.

In a desperate attempt to block the marriage, Enrique took Isabel's mother away and kept her in isolation in the castle at Arévalo. Knowing that Isabel would follow her, he had conceived a plan that would imprison them both away from her advisors without the use of force. He could now lead her into a marriage with Luis, whose father had died and who had now become the King of France.

Isabel’s mother was deteriorating mentally and she suffered bouts of hallucinations an frequently could not recognise her own children. Alone, and in great danger, Isabel was constantly badgered to sign a marriage proposal from the French King. One of her trusted friends rode to rescue her, bringing a gift from the King of Aragon, a necklace of rubies and pearls. Isabel made up her mind in an instant and rode off with him, leaving her mother with her enemies.

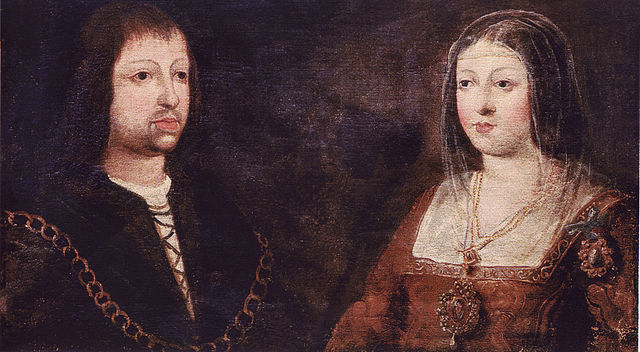

So far, Isabel and Ferdinand had never met. The capitols of the two kingdoms were two hundred miles apart, and Enrique controlled the borders of Castile. Ferdinand disguised himself as a servant, and with two aides, passed over the border into Castile to meet with Isabel. To everybody’s delight, the two fell in love, and the wedding plans accelerated.

Enrique's only hope of stopping the wedding now was through the Church. His spies had discovered the weak point in their plans. A papal bull had been drawn up by the previous pontiff, Pius II, allowing second cousins to marry, but he died before he could sign it. Through the bishop of Toledo, Isabel and Ferdinand had been petitioning his successor, Pope Paul II, to uphold the bull and give the marriage his blessing. The Pope refused, and the marriage of Isabel and Ferdinand was forbidden.

The nobles and the church realised that they had a winning team with Ferdinand and Isabel. Their marriage would stop the constant wars that were bankrupting their kingdom. Enrique was a total embarrassment, but putting him out of the battle for the crown would not be easy. Desperate times call for desperate measures, and the Bishop of Toledo, with the backing of the clergy, managed to obtain the old unsigned papal bull granting the second cousins the right to marry. He forged the dead pope’s signature on the bull and showed it to Isabel. Isabel and Ferdinand were delighted that they had the permission of the pope for their wedding, but Enrique’s spies also had friends in the clergy, and a letter was delivered to Isabel by one of her friends telling her of the deceit. Isabel was furious that her trusted advisors would lie to her and lead her into a trap. With great tact, they persuaded her that the pope would be led by events. If they married, then he would be forced to give his consent.

Isabel allowed her heart to rule her head, and in the greatest secrecy, Isabel had her mother and handmaiden friends brought to her side. They were all with her when she married Ferdinand at the Palacio de los Vivero in Valladolid on 19 October 1469.

The true power over the kingdoms had now passed to Isabel, effectively uniting Castile, León and Aragon to form the basis for one state, which became the nascent country called after its ancient name of Hispania, and later changed to España. The united kingdoms still continued to govern themselves as separate entities, but the seeds had been sown for something greater.