A lost genius

Thursday, February 8, 2024

On July 17 1936, 34 year-old Captain Virgilio Leret of the Spanish Air Force was relaxing with his wife, Carlota Leret O’Neill, and his two daughters, Maria Gabriela and Carlota. He had rented a yacht and anchored it just off the Atalayón Hydroplane base in Melilla in North Africa, where he had been posted as base commander. The yacht was an ideal place to escape the July heat of the African coast and his family had joined him for a short holiday. This was the summer holiday season when the Spanish flocked to the coasts. This yearly exodus to escape the heat was called to verano. The base was deserted with nearly all the aircrews and maintenance men on holiday with their families. Leret had few urgent duties at the base, and it was ideal for him to row out to the yacht to be with his family when he was not busy.

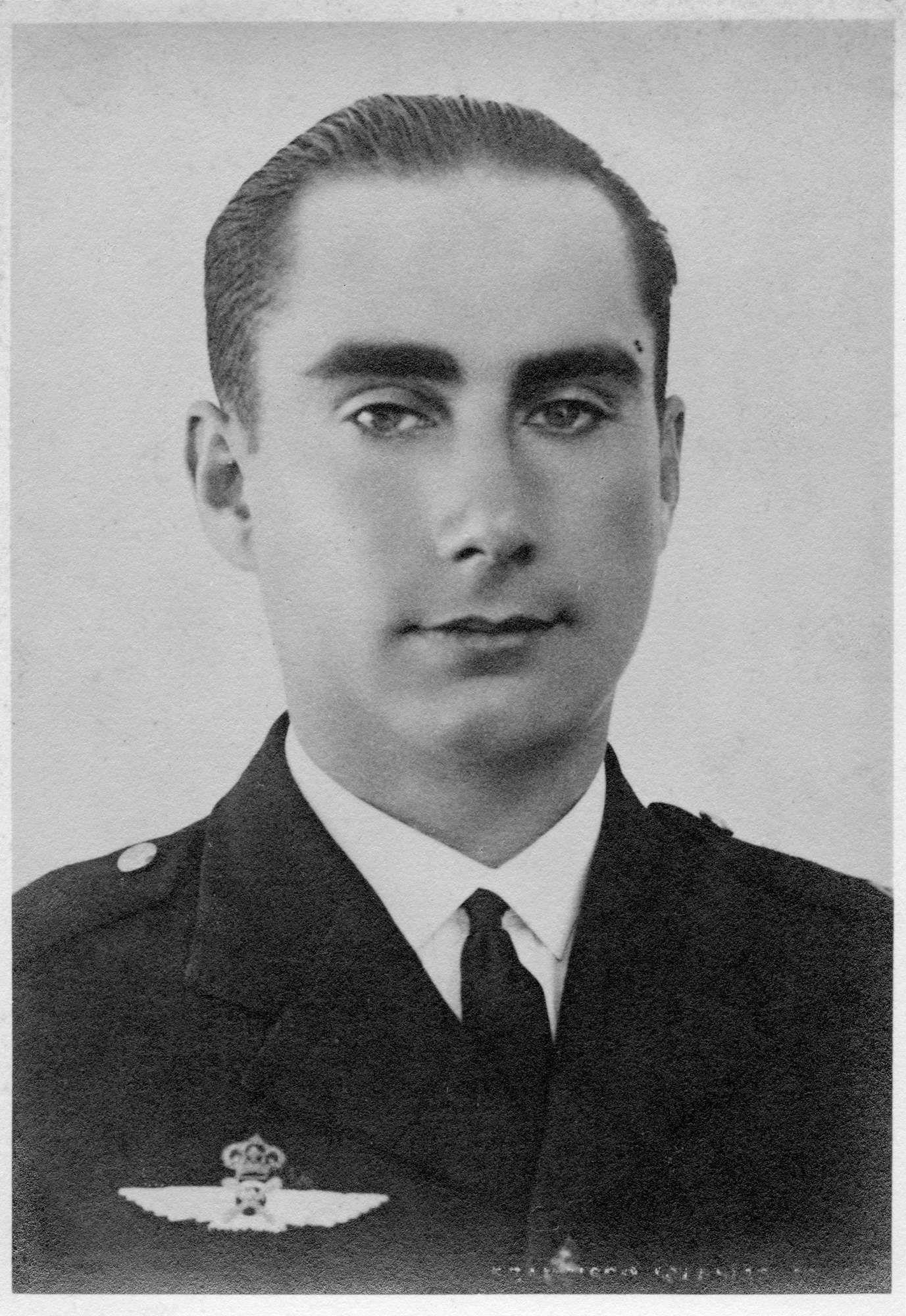

Vigilio Leret Vigilio Leret

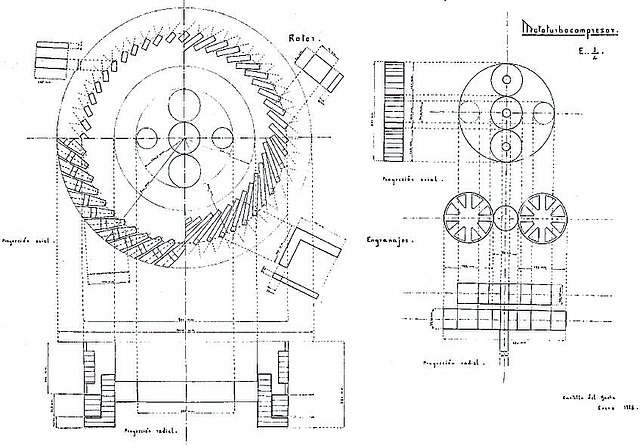

Leret was an exceptionally gifted engineer and was about to begin the production of an invention that he had been working on for the last few years. The year before, he had patented the design of “The turbo compressor continuous combustion engine como propulsor de aviones, y en general de todo clase de vehículos.” No less a dignitary than the Prime Minister of the Republic, Manuel Azaña, was about to order that production of the new motor would commence in September 1936 at the Hispano Suiza de Aviación engineering works. Three months earlier, on April 29, Azaña had made him professor of the mechanics’ school at Cuatro Vientos airfield near to Madrid. He had already been given his posting to El Atalyón , but had stayed on at Cuatro Vientos until May. Leret was killing time before he became a consultant in the manufacture of his jet engine.

(Sir Frank Whittle was the first to patent the jet engine in 1930,then Leret’s design was patented in 1935, with the German physicist Hans Von Ohain coming last when he patented his version of the jet engine in 1936.)

The Leret turbocompressor.

Leret’s career in the air force had not been without complications. He had followed in his father’s footsteps and joined an army academy at 15 years-old. He graduated top of his class in 1920 as a Second Lieutenant. One of his first postings in May 1921 was to the Campamento de Aviasión de Sania Ramel, the first airport in Spanish Morocco. This was to be his introduction to aviation.

After this he spent time in various infantry divisions in mainland Spain and it was during one of these tours that he met the woman who would become his wife, Carlota O’Neill y de Lamo, who was working as a left-wing writer. He had already tried to take the army’s military pilot course, but he had been unable to complete it because of other duties. In March 1926 he was at Los Alcalázares where he started training as an observer. This was also interrupted by first an air accident that hospitalised him for month and then malaria that took him three months to recover from. A year later, in October 1927, he qualified as a civilian pilot and the following January he completed his military pilot training.

In November 1928 he wrote to Carlota asking if she would marry him “as a social defence for the future”. She had already given him two daughters, and it was at his father’s request that he had proposed. On February 10 1929 he married Carlota, but Virgilio’s staunchly Catholic family ignored his children because they had been conceived out of wedlock. Nevertheless, Leret continued with his studies and in 1929 he qualified as an electromechanical engineer after completing a correspondence course.

However, storm clouds were gathering over Spain, and the military was becoming a hotbed for dissent. Some of this was over pay and the lack of promotion prospects, and many of the career officers were actively supporting dissent.

On December 15, 1930, Leret and some of his fellow officers refused to pursue General Queipo de Llano and Air Commander Ramón Franco who had escaped by air after a failed military uprising at the Cuatro Vientos airbase. This came three days after the Jaca uprising. His superiors sentenced him and eleven others to prison and discharged them from the army. Things moved quickly, and within three months the Second Spanish Republic had been proclaimed. Leret and his comrades were released and restored to their previous rank and pay in the army.

In May 1932 Leret took the seaplane course at Melilla which he completed in February 1933. He was in trouble again when he publicly denounced a political military broadcast and was sentenced to two months’ imprisonment in the fortress of El Hacho, Ceuta. It was whilst he was in prison that he finalised the design of his jet engine.

His troubles were all behind him now and he was enjoying the swimming, fishing, late dinners and long siestas with his family on the yacht. Their holiday continued for two weeks until Friday July 17, when at midday they heard gunfire at the base. Shortly after, Armando González Corral and Luis Calvo Calavia, two of his fellow officers at the base, rowed a boat out to the yacht and told him that the base was under attack from the Nationalists. Leret picked up his gun and hat and kissed his wife before joining the other men in the boat. As they rowed away, Carlota watched the face of her husband, who never took his eyes off of her. She never saw him again.

At the base Leret discovered that a column of Regulares led by the Francoist Moroccan officer Moham Meziane were advancing on Melilla and had stopped to take the airbase. Hopelessly outnumbered and with little ammunition, Leret defended the base for around two hours until the ammunition ran out. They surrendered, and the Regulares severely beat Leret and his men and threw them in prison. The following morning they were taken out and shot. One report states that his own officers were forced to shoot Leret. They were the first casualties of the Spanish Civil War.

Carlota knew nothing of events until the Moroccans came to the yacht and took her ashore the same morning that her husband was killed. Five days later, she was officially arrested as a suspected “red” and thrown into prison. Carlota was handed four suitcases that had been on the yacht. The Moroccans had been lax and had not searched the cases assuming that they contained only clothes; but one of them contained three sets of plans for Virgilio’s jet engine. She was not told what fate had befallen her daughters.

Afraid that the plans would fall into the hands of the Francoists, Carlota made plans to smuggle them out of the prison. One of the other inmates was Ana Vásquez, who had been put in prison for prostituting her own daughters. Ana was not suspected of any political involvements, so was told to keep an eye on the “reds” and inform on them. Instead, Ana helped Carlota smuggle the drawings out wrapped in dirty laundry. The drawings were collected on the outside by the son of another inmate whose mother had been imprisoned after her husband had been shot. He hid them under a loose floor tile in his house.

Carlota was tried three times by a military court and sentenced to six years in prison. The Spanish Civil War raged on, and at one point when the Falangists had taken Toledo, a group of soldiers came to the prison and demanded some women to shoot in celebration. Carla hid in a water tank with just her nose out of water. She remained there all night and only came out when the Falangists had gone.

She was released in 1941 and immediately went to the now deserted house where the plans had been hidden. After a short search through sand and rubble she found the loose tile and the drawings beneath. The dry desert air had preserved them in near pristine condition.

The Spanish Civil war was over, with the Caudillo brutally ruling over a starving, impoverished and demoralised Spain. Outside of the “allegedly” neutral Spain, the Second World War was escalating in ferocity, with Hitler invading Russia in June 1941 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December. If ever the free world needed a secret weapon it was now.

Carlota could not possibly have known about the top secret work on jet engines of Frank Whittle or Hans Von Ohain. She only knew that her husband’s plans must not fall into German hands. Carlota had found one of her daughters by now, and they both took one set of the plans to the British Embassy where they met James Dickson the aviation attaché.

She gave Dickson the plans, but he was killed in an accident shortly after they met. Carlota never found out what happened to the drawings that she gave him. Over the next few years, Carlota made contact with her other daughter, but wherever she went she took the remaining drawings with her.

Carlota Leret O’Neill finally settled in Caracas, Venezuela, as an exile with her daughters. She died in 2000 at the age of 90. Her youngest daughter, Carlota, began to show her father’s drawings in an effort to draw attention to his work. In 2011 Spain’s AENA’s national airport authority financed a documentary on Spanish television about Leret’s work. Later, Carlota took the drawings to the Museo del Aire in Madrid. They were impressed, but lacked the funding to mount a display of her father’s engine.

“They were excited at the museum but they told me they didn’t have the money to build and mount the engine”. Carlota toured engineer’s workshops and finally ordered the building of a replica of the engine. This was paid for with her own money, and she won’t reveal how much it cost, although some of the money was raised from the sale of her mother’s memoirs.

The Turbo Compressor engine took 2,500 man-hours to build and comprised of 2,674 parts. In the Ministry of Defence’s 2002 publication, Aeroplano, aeronautical engineer Martin Cuesta wrote, “Had he not been shot his engine would surely have become a reality with the resulting honour for its creator and for Spain.”

Three hundred and ninety pages long, Carlota O’Neill’s book, Una Mujer En La Guerra De Espana, is a heart-rending story of poverty, prison and exile which is, above all, long declaration of her love for her husband, who was probably the first victim of the Spanish Civil War. His body was never found and there are no records of his grave.

Sources: Most of this story was taken from El Pais and Wikipedia. Carlota O’Neil’s books are on sale from Amazon.

4

Like

Published at 3:39 PM Comments (6)

4

Like

Published at 3:39 PM Comments (6)

The flights of Gran Poder

Thursday, February 1, 2024

In 1928, 11 years before Franco came to power, when Spain was governed by King Alfonso XIII and his wife Victoria Eugenie (granddaughter of Queen Victoria and Albert) two officers in the Spanish armed forces set out to claim some aviation world records for Spain. During the early part of the last century aviators were setting new records for distance every other week. Most people know the greats, Alcock and Brown, 1919: first transatlantic flight, Lindbergh 1927: non-stop New York to Paris, Bert Hinkler 1928: England to Australia solo.

The aircraft they were going to use was a Breguet 19. The design was a sesquiplane, a form of biplane with one wing with less than half the area of the other (usually the lower wing). Originally designed as a long range bomber and reconnaissance aircraft, the type had first flown in March 1922. It had a top speed of 214 km/hour and a range of 800km.

Breguet 19

Rather than buy the aircraft from Breguet, The Spanish authorities decided to buy the rights to build their own aeroplane. (Something that many modern countries choose to do to create their own manufacturing technology). The aeroplane was constructed by the C. A. S.A. workshops and christened “Jesus Del Grand Poder” in honour of Queen Victoria Eugenie.

The officers who were to fly her were both captains in the military, but it’s not clear if they were in the Spanish air force or the Spanish army. However, both photographs show them with wings on their tunics.

Pilot: Capitán D. Francisco Iglesias Brage. Who was named as official engineer, scientific advisor, and the man who organised and planned the flights.

His co-pilot, Capitán Ignacio Jiménez-Martin, (Recorded as a captain in the Spanish infantry.)

Their first try at a long distance flight was in March 1928, when they did a non-stop circuit of Spain covering 5,100km. This was to prove that the aircraft and crew were capable of a long duration flight.

With this successfully accomplished, they planned a flight from Seville to Iraq. If successful, they could claim a speed and distance record. The distance was slightly longer than their test flight (5,200km.) and over much more rugged and desolate terrain. They took off on 29 May but their attempt was thwarted when they encountered a sandstorm which ruined their attempt at a speed record. The journey took 28 hours which was too long to claim a record. The first lesson was that adverse winds on the day could ruin a speed attempt. By design or accident they landed at Naziryah, 150km. north of Basra, but flew on to Basra after a short rest.

The return journey was to be less demanding. The first stop was Constantinople, a distance of 2,200 km. which they covered in 13 hours 15 mins. From here they flew direct to Barcelona, a distance of 2,270km., covering the greater distance in the same time as they took to reach Constantinople: 13 hours 15 mins. Next, they made a relatively short hop across Spain to Seville via Madrid.

Over the winter of 28/29 the Gran Poder team planned a truly gigantic leap into the unknown that must have taxed their fortitude. A flight from Seville to Bahia in Brazil, a distance of 6,550km over the Atlantic Ocean, one of the most unpredictable oceans in the world. When they flew to Basra they would have selected to fly over, or at least know the location of every airfield on the route. The open desert would have been daunting, but if people knew your route rescue parties could follow your planned course in the event of a forced landing. Over the open ocean there was no safety net. In the event of a forced landing Gran Poder and her crew would disappear without trace.

On April 30 1929 they wheeled the Gran Poder out of its hanger at Tablada, an airfield near to Seville, and made the final checks. The range of the aircraft had been increased with the addition of internal fuel storage that had turned the aeroplane into a flying fuel tank and greatly increased its take-off weight. After a long run to gain speed, the Gran Poder left the ground and slowly climbed as it headed south.

Forty-four hours and twenty minutes later it touched down at Bahia in Brazil after covering 6,550 km. non-stop.

After a few days rest for refuelling and maintenance checks, the two pilots flew the aircraft a further 800 km. to Rio de Janeiro in 8hours 28 minutes. They continued down the coast of South America, crossed into Uruguay, and landed at Montevideo, a distance of 2.300km. This leg had taken them 13 hours, and from here they made a short hop across the River Plate to Buenos Aires.

They had to plan the next stage of the flight very carefully. The flight from Buenos Aires to Santiago was 1,250km. But the city of Santiago is at an altitude of 600m. above sea level and it’s in a valley surrounded to the east by the jagged peaks of the Andes which tower to 6,000m. A local peak close to Santiago is the 5,434m Cerro el Plomo . To make matters worse, the hollow that Santiago sits in is frequently enveloped in mists; a nightmare for any pilot who is unfamiliar with the terrain or local landmarks. The fuel for the Gran Poder had to be calculated so that they would not be too heavy to cross the highest passes, but still leave them a generous safety margin.

During modern times, four engined passenger planes have set off to cross the Andes and discovered that once they reached an altitude that would ensure that they cleared the highest peaks they suddenly stopped moving relative to the ground below. They had entered a higher weather system between the Pacific and Atlantic that regularly saw winds of 400km/hour.

In the event, the two pilots managed to cross the Andes and their good luck held as they emerged into the clear broad valley in which Santiago sits. The landing was uneventful.

When they recorded the flight time, they realised that their speed over the ground during the flight had been 160km/hour whilst their flying speed had been 200km/hour. The headwinds had been mild and they had been lucky. Their flight time had been only an hour longer than they had planned.

Had the headwind been any greater, they would have had to make a forced landing in the Argentine wilderness. This flight was a first for a Spanish aircraft, and when they reached Peru the crew were to be presented with a certificate recording their achievement.

After descending from Santiago to near sea level, their next stop was Arica, on the border between Chile and Peru. This was an 1,800km. leg which they covered in 11 hours. After an overnight rest and some aircraft checks they took off for their next stop, Lima, Peru; a distance of 10,050km. This was achieved after an uneventful flight of 7hours. From here they made a relatively short hop of 920km. to Paita, before setting off again to cross the Equator and land at Colon, Panama, a 10 hour flight that covered 1,920km. Their penultimate flight was a 9 hour flight to Managua, Guatamala, a distance of 1,550km. Finally their last flight was an 8 hour leg across the Caribbean to Havana, Cuba.

The distance by air from Havana to Seville was over 8,000 km. and beyond the Gran Poder’s range. The aircraft was dismantled and loaded onto a cargo ship for the journey home.

When they re-assembled the Gran Poder in Cadiz two local artists who are recorded as Lafita and Manzano painted figures on the fuselage representing people from each of the countries they had visited. Flags and coats of arms of some the countries were also copied onto the aircraft. The two pilots then flew from the aircraft Cadiz to Seville, their starting point, and then on to Madrid where they were given a welcome fitting for two of Spain’s heroes.

It was now October 1929, but this was not the end for Gran Poder. Her two pilots returned to Seville from Madrid then returned to Madrid to begin another round of flights to North Africa, landing at Melilla, Tetuan, Larache before finally returning to Madrid.

There the Gran Poder stayed parked in a hanger for a year whilst the world forgot about her. In December 1930 she was brought out of retirement to fly to Casablanca and back, and the following May she flew to Barcelona and back. In June that same year she flew to Northern Spain landing at Logrono and Leon before returning to Madrid. Her final flight was from Madrid to Rome and back, a distance of 3,200km. The Gran Poder remained in Madrid during the Spanish Civil war and World War 2, but in 1952 the Museo de Cuatro Vientos in Madrid finished their restoration of this record breaking aircraft and it became a permanent exhibit there.

During its lifetime, the Gran Poder had flown a total of 47,805 km. and its flying hours totalled 273 hours 51 mins. In 1995 an artist painted this picture of the Jesus Del Gran Poder in flight and it hangs next to the aircraft in the museum.

1

Like

Published at 9:25 AM Comments (7)

1

Like

Published at 9:25 AM Comments (7)

Sailing on a silver sea

Thursday, August 31, 2023

Balboa’s luck seemed to have run out, but fate stepped in to give him a last reprieve. The colony’s newly appointed, Bishop de Quevedo, intervened and cautioned Pedrarias about abusing his power. The church still had considerable authority here in this far-flung outpost, and a reluctant Pedrarias moderated the harsh treatment he had planned for Balboa.

Pedrarias must have been furious, but worse was to follow for the governor. If Balboa had a guardian angel she must have been working overtime in Spain.

King Ferdinand died in January 1516, and whether it was a last wish of the king, or a decree from King Charles I, his successor, I am not sure, but shortly after his incarceration came notification for Pedrarias to show Balboa the greatest respect and from now on to consult him on all matters pertaining to the conquest and government of Castilla de Oro. This must have been hard enough to swallow, but worse was to come. For his valuable services to Spain, the king bestowed on Balboa the titles of "Adelantado de los mares del sur" and "Gobernador de Panama and Coiba". This, of course, meant that Pedrarias had to immediately release Balboa and his men.

In an attempt to dispel the rivalry between the two men, and what has to be said is a bizarre solution to the problem, the Bishop and Isabel de Bobadilla arranged for Balboa to be married to one of Pedrarias’ daughters. However, she lived in Spain and had no intention of moving to the colony. It was to be a marriage of convenience and proxy and arranged by the bishop, and for a while it worked. Balboa learned to show respect and affection toward his father-in-law, but there was still that cruel, distrustful streak in Pedrarias that had earned him his evil reputation. The Bishop de Quevedo returned to Spain, but Isabel de Bobadilla was to become a woman of considerable power and respect in the future of Spanish exploration and influence in the Caribbean.

In Spain, the new discoveries were exciting the already rich and powerful nobility. The marriages that Isabel and Ferdinand had arranged for their children were paying great dividends in the powerful royal families of Europe. Even without the New World discoveries, Spain was on a trajectory would make it one of the most powerful nations in the world.

Balboa’s fascination with the South Sea continued to occupy him, and despite Pedrarias hindering every attempt by Balboa to organise a new expedition, he finally agreed to give him an 18-month licence to explore the southern sea.

Balboa gathered the carpenters and shipbuilders that he wanted for building new ships on the other ocean. He employed native guides and warriors for defence, and took along African slaves as porters. The small army of 300 that Balboa had gathered sailed up the coast to establish a staging post which they named Acla. From there they crossed the isthmus and arrived at the mouth of the Rio Balsas where they began the construction of four ships. Once the ships were finished and tested, Balboa took the flotilla out into the southern sea. He sailed south along the coast of what is now Darien and then explored further west around what is now the Isla del Rey, finally sailing back to the coast north of his starting point and following the coast south and returned to the Rio Balsa with the intention of building bigger boats.

On his return, he was given letters from his father-in-law which warmly expressed a desire to hear all about his voyage first-hand. Balboa set off back across the isthmus, but half-way met his old companion, Francisco Pizarro.

There was no welcome however. Pizarro was under orders to arrest Balboa for trying to usurp Pedrarias’ power as governor by starting a rival colony at Acla. Balboa was outraged that such an accusation should be made. He had asked and been granted permission from his father-in-law before he set off. He demanded that he be tried in Spain, but Pedrarias together with Martin Enciso forced through the trial and Balboa, Fernando de Argüello, Luis Botello, Hernán Muñoz, and Andrés Valderrábano were accused as accomplices and were sentenced to death by decapitation. The sentence was to be carried out in Acla, to show that the conspiracy had its roots in that colony.

As the men were led to the block the town crier read out the charges and to emphasise the governor’s power he added, "This is the justice that the King and his lieutenant Pedro Arias de Ávila impose upon these men, traitors and usurpers of the Crown's territories."

Balboa shouted his plea of innocence to the crowd.

"Lies, lies! Never have such crimes held a place in my heart. I have always loyally served the King, with no thought in my mind but to increase his dominions."

They were to be his last words. The executioner beheaded them all one-after another other with an axe. Pedrarias seemingly watched the executions from behind a platform and out of sight of the crowd in case there was a rebellion. Their heads were put on public display as a sign of his power.

.jpg) Monument to Balboa in Darian. Photo:Chico Monument to Balboa in Darian. Photo:Chico

In the years that followed, Acla fell into disuse and the jungle reclaimed the site of the settlement. Pedrarias also disappeared from history except for being noted as a cruel evil governor of a tiny settlement. Balboa, however is remembered as the man who discovered what a later explorer would name the Pacific Ocean.

With corruption, betrayal and the lust for power and gold firmly established in the New World, Spain was about to have another lucky break that would eventually make it a truly world encompassing sea power. The King of Portugal was discouraging all exploration of the New World for fear that it would upset his monopoly on gold and spice trade with the far-east. This was to incite some of his more adventurous explorers to leave Portugal and move to Spain. Balboa’s discovery of a new ocean had revitalised an old dream that had died with Columbus; a westerly passage to China and the far-east.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The area of Balboa’s settlement at Santa Maria is now a part of the province of Darien. It is also the location of the infamous Darian Gap. Europe has a huge problem of dispossessed refugees from corruption, war and dictators. Central America has the same problem. The gap gained its name from the gap in the Trans America Highway which runs from Alaska to the southern tip of Argentina. This 60 mile gap in the highway has claimed the lives of thousands of refugees fleeing the oppression and exploitation of the drug barons and corrupt politicians in South America.

In 1972 a team of British explorers led by Colonel John Blashford -Snell attempted the first vehicle crossing of the Darian Gap in two Range Rovers. Blashford -Snell has led over a hundred expeditions all over the world, but the Darian Gap proved to be one expedition too far. The expedition took several months to cover the 60 miles during which the 11 of the Columbian army support group who accompanied the expedition were killed and 50% of the rest of the team evacuated as medical casualties. There is still no permanent road across the Darian Gap.

Photo: Ass Press

The only connecting links are dirt tracks through the expanse between Columbia and Panama. The surrounding countryside is made up of some of the most dangerous and difficult terrain on the planet, with vast swamps and steep mountains covered in dense impenetrable rainforest. Nevertheless, tens of thousands of refugee families each year attempt the crossing in their desperation to find a better life. Not only do they face the daunting terrain, but the indigenous fauna. Several breeds of poisonous snakes and pumas prowl the jungle. To add to this are the local gangsters who charge a high price for safe passage through their territories. One of them, The Gulf Clan, a Columbian paramilitary group, have established a transit camp at Las Tekas in Columbia to “process” the migrants who pay them huge amounts to allow them to make the crossing under the supervision of their “coyotes” or guides. The ten day journey takes a heavy toll on the refugees who are often carrying children. Rape, robbery and sexual trafficking are additional extras the may have to suffer. Many die on the way.

Jean Gough, regional director of Latin America and the Caribbean UNICEF said in an October 2021 news release: “Week after week more children are dying or losing their parents, or being separated from their relatives whilst on this perilous journey.” UNICEF estimates that half the children who crossed in 2022 were under five and at least five hundred were unaccompanied. UNICEF records that 36 people died trying to cross in 2022, but the figure is likely to be much higher.

According to Panamanian migration officials 88,000 people have made the crossing in 2022 and the number is expected to rise to 400,000 in 2024. Armed bandits who are trying to take over Haiti are causing thousands of displaced refugees to flee to the US where they are hoping they can claim asylum. The Panamanian authorities and international aid organisations have set up camps on their side of the gap, but the numbers arriving have quickly swamped their facilities.

After the 2010 earthquake in Haiti many of Haitians fled to South America where they faced persecution. In 2021, 61% of those crossing the gap were from Haiti, but now the bigger percentage is from Venezuela as humanitarian conditions in their own country deteriorate. Ninety-five percent of the population of Venezuelans live in poverty with 76% of them in extreme poverty and in 2022, 2.5 million Venezuelans registered for temporary protection status in Columbia with Brazil granting 345,300 residency permits to Venezuelan refugees.

It is easy to speculate that if the Spain of 1520 had chosen the leaders of its new colonies more carefully, then this circle of corruption and violence might never have got started.

In a book called Why Nations Fail, written by Darren Acemoglu and James A Robinson, the authors suggest that rule by conquest and subjugation set the standard for how all South America would be governed. The primary Spanish aim of expeditions into the interior was the extraction of gold. To this end, the invaders seized the chiefs and kings of the territories and held them to ransom, demanding gold be delivered for their release. They were often tortured to death to extract all the gold in their kingdoms.

These were the tactics of Pizarro when he conquered Peru, when he: “Set out with every intention of imitating the strategy and tactics of his fellow adventurers in other parts of the New World”. Spain went on to create a web of institutions to exploit the indigenous people and force their living standards down to subsistence levels. This turned Latin America into the most unequal continent in the world.

The same thing was tried when England set up its first colony in the New World. England was a late starter, and it was only when Elizabeth’s navy had defeated the Spanish Armada in1588 in a very lucky series of battles off the south coast of England that England could dare to challenge the Spanish control of the Atlantic. Eager to grab a slice of the action in the New World, the English founded the colony of Jamestown in 1607. The English chose North America because it was all that was left; Spain controlled all the rest of the Americas. The British had exactly the same game-plan as the Spanish, which was to conquer and exploit the natives. They had no idea that they had picked the worst place possible to start their conquest. Twenty miles from Jamestown was the camp of Wahunsonacock, a chief who controlled a small empire of 30 tribes. Leaving aside the story of Pocahontas and John Smith, the colony ran into serious difficulties. The natives would not co-operate and give them food, and the colony began to starve, culminating in the winter of 1609. Out of 500 settlers only 60 survived the winter. After that, the Virginia Company, which had funded the entire enterprise, realised that to encourage new settlers (and some profits) they would have to do things differently.

It took nine years for the company to realize that treating the settlers as slaves would not work. They were given their own land and freed from their crippling contract with the company. After that, the settlers fought to remove all the controls that the British tried to force onto them. In 1619, a General Assembly was introduced which gave all men a say in the laws and institutions which governed the colony. This was the start of democracy in what was to become The United States of America.

0

Like

Published at 8:09 AM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 8:09 AM Comments (0)

A whole new world

Thursday, August 24, 2023

In the space of three years, Vasco Núñez de Balboa had come from being a bankrupt stowaway to the governor of the only settlement on the American mainland after ousting the two governors appointed by the King of Spain. He had performed this minor miracle whilst living in the most inhospitable jungle and facing ferocious natives; but Balboa was just getting started.

In late 1512 he entered the territory of the cacique Careta who rallied his warriors to defend their lands. He defeated the chief, but later befriended him. Subsequently, he converted him to Christianity and had him baptized. From then on, Careta became one of his best native allies and gave the Spaniards food to help sustain the colony. Careta might have had an ulterior motive, because he and his tribe had an enemy in the nearby villages of the cacique Ponca, and Balboa and Careta unified their forces and attacked Ponca’s villages. Overcome by this overwhelming force, Ponca and the remains of his tribe fled into the jungle leaving their village to be plundered. Balboa’s new army moved on to the tribal territory of Cogmore, another cacique. This time there was no battle and they were welcomed by Cogmore who organised a feast in their honour. Later, he also agreed to be baptized.

Wherever the Spaniards went, their preoccupation for gold was noted by the natives. In a society where gold was just an easily worked ornamental metal that had no other value, this obsession must have seemed very strange. Balboa’s men were complaining about the meagre amounts of gold that they were being allocated as their reward for living in such a hostile environment. It was during one of these periodical share-outs of the gold booty that a squabble broke out amongst the Spaniards. The eldest son of Cogmore, Panquiaco, was watching and he stepped forward and knocked over the scales used to measure each man’s share.

He shouted to the Spaniards: "If you are so hungry for gold that you leave your lands to cause strife in those of others, I shall show you a province where you can quell this hunger.” He told them of a kingdom to the south where people ate their food from plates of gold and drank from golden goblets. The Spaniards, who had now fallen silent, listened as Panquiaco warned them that they would need at least a thousand men to defeat the tribes living inland and those on the coast of the other sea.

Balboa was told of this outburst and, like one of his hunting dogs, his ears pricked up at the promise of so much gold. He was also intrigued by Panquiaco’s reference to the “other sea”. He decided to mount an expedition to explore inland. Balboa had taken note of the need for a stronger force to overcome these other tribes and in 1513 wrote a letter to the King of Spain asking for more men who were already acclimatised to the tropical heat. Ideally they should be from Hispaniola. He also requested that he be supplied with provisions, weapons and carpenters who were versed in the building of ships. His ambitious plan was to find the source of all this promised gold as well as this curious “other sea” and build a shipyard there to explore it. In early 1513 he returned to Hispaniola to recruit more men. Unfortunately, Fernández de Enciso, one of the appointed administrators that Balboa had ousted, had spread the word that Balboa was an illegal usurper of the title of governor. He was told that there would be no further assistance from Hispaniola for his expedition.

Undaunted, Balboa dispatched his friend, Enrique de Colmenares, directly to Spain to plead his case with the king, but news Balboa’s take-over had reached the Spanish courts and he was denied assistance. He returned to Santa Maria empty handed and decided to mount an expedition with the meagre forces that he had in the settlement. After gathering information from the friendly native chiefs he began planning the route of his expedition. Whilst he had been waiting in Hispaniola for a reply to his letter to the king, another expedition from Santa Maria had made an attempt to follow the Rio Atrato, but after 30 miles they saw no tracks or villages and returned. There was no easy way to penetrate inland; every mile would have to be cut through a dense and often boggy jungle. Only native guides who knew the land would be able to lead Balboa through to the “other sea”. On September 1, 1513 Balboa set off from Santa Maria aboard a brigantine leading a small flotilla of 10 native canoes. In total there were around 190 Spaniards plus Balboa’s secret weapon, a pack of his hunting dogs. He also had a military contingent under the command of none other than Francisco Pizarro. They sailed up the coast to the village of the cacique, Careta, who joined him with 1,000 warriors to enter the lands of his old enemy, Ponca. After following the Rio Chucunaque they found him and his warriors on September 6 and immediately attacked.

Ponca had regrouped his villagers but the battle was a forgone conclusion and Ponca surrendered. The terms were not unjust and he agreed to ally himself with Balboa and Careta. By September 20, the force was ready to move inland again, this time against the next cacique, Torecha, who ruled in the village of Cuarecuá. It took four days of hard cutting through the jungle to reach the village and Torecha was ready for them. He met the Spaniards in force and a fierce battle ensued which only ended when one of Balboa’s hunting dogs killed Torecha. Faced with no alternative, Torecha’s tribe agreed to join Balboa’s army. By now Balboa had many wounded men and all were weary from the hard passage through the jungle. His men decided to camp in the village to recover their strength.

Balboa, however, gathered a small contingent of men who were eager to continue the next day. The natives that he had questioned had told him that he would be able to see the “other sea” from the range of mountains immediately in front of them and less than a day’s climb away. Balboa made better headway than the others, no doubt wishing to claim to be the first to see the “other sea”. He was rewarded just before noon on September 25, 1513 when he reached the crest of a hill and saw in the distance what would later be called the Pacific Ocean. As one-by-one the others caught up, they were awed at the sight, and Andrés de Vera, the expedition's chaplain, intoned the Te Deum. Meanwhile, others erected stone pyramids and carved crosses into the bark of nearby trees to mark the site of the discovery.

Picture: Alan Pearson

I think that Balboa had grasped the significance of the “other sea” immediately. All the expeditions from Spain, including the first one by Columbus, had one overriding motive; to find a westerly trade route with China and the orient, and here it was. Balboa had been incredibly fortunate. From Cabo Gracias a Dios at the northern end of Veragua it would have been a 400mile trek through the most inhospitable jungle in the world to reach the Pacific. Similarly, from Cabo de la Vela in Nueva Andalucía it was a journey of around 500 miles and a crossing of the northern end of the Andes before you could reach the Pacific. But here, so close to the first settlement, was a crossing of only 60 miles to the gateway to the Orient. It would not have been an unreasonable task to drive a track through the jungle and establish a port on the western side of the isthmus and from there sail across to China. This, in fact, is what Balboa had proposed to do when he wrote to the king asking for carpenters and shipbuilders.

(Starting in 1532 the looted gold from the Inca Empire was ferried up the western coast of South America and brought to Panama where it was loaded onto mule trains which crossed the isthmus along the Camino Real to Nombre de Dios. Here it was loaded onto ships which took it directly to Seville. By 1572 the Incas were conquered, and the flow of gold to Spain was at its height. A fact that had not gone unnoticed by an enterprising English sailor called Francis Drake, who in 1573 made a very famous and daring raid on one of the mule trains. He made off with enough gold from the 190 mule-long train to equip his ship, the Pelican, for a circumnavigation of the world. He also greatly impressed his queen, Elizabeth I. But that’s another story.)

Balboa returned to Santa Maria knowing that he was sitting on a veritable gold mine, making his situation very dangerous. Many of the high-born Spanish officials were reluctant to risk their lives in jungles full of hostile natives, but once it was civilised and safe, they could use their wealth and power to move in and take over. He had made plenty of enemies in his rise to power. Fernández de Enciso, whom Balboa had sent packing, had been busy in the royal court maligning Balboa and reporting the mysterious disappearance of Diego de Nicuesa, the old governor of Veragua.

The king decided to appoint Pedro Arias de Ávila as governor of the newly-created province of Castilla de Oro. He was to be the new governor of Veragua and he set off from Spain at the head of the largest fleet ever to sail to the New World. Seventeen ships and 1,500 men were to land at Santa Maria and take control of the colony. Martín Fernández de Enciso, returned as Alguacil Mayor, the Chief Constable of the colony. Franciscan friar Juan de Quevedo was appointed bishop of Santa Maria and Gaspar de Espinosa was to be the Alcalde. Also, there was to be a royal chronicler, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. There was to be no official post for Balboa.

They arrived in Santa Maria in July 1514 and the New World had prepared a welcome celebration of its own for the new arrivals. Several storms battered the colony, and the crops that had supported the colonists so far were not sufficient to support the newly enlarged population. Balboa had wisely requested troops who were acclimatised to tropical conditions, but the newcomers were decimated by hunger fever and disease, and 500 men were lost within the first few months after landing in Santa Maria.

Balboa was magnanimous in defeat, and resignedly accepted his replacement as governor and mayor, but the settlers did not. Their new governor, Pedro Arias de Ávila, better known later as Pedrarias Dávila, would become known throughout the colonies as a brutal, cruel tyrant. They were preparing to start an insurrection when Pedriarias had Balboa arrested and ordered him to pay reparations to Fernández de Enciso. There was also a murder charge brought against him concerning the disappearance of Nicuesa, but he was found innocent and released. Despite the early fatalities amongst the new arrivals the small colony was still overpopulated, and Balboa asked for permission to search for a location for a new settlement to ease the overcrowding. This got him out from under the heel of Pedrarias for a while, but during an attack by the natives he was wounded and forced to return to recover. His subservience to Pedriarias, whose malice was unchecked by any higher authority, must have been misery for Balboa after all that he had achieved. In desperation, he sent word to Cuba that he was going to recruit men to cross the isthmus and set up a small shipyard in the Southern Ocean away from the stifling influence of Pedriarias. The ship carrying his recruits made landfall along the coast from Santa Maria and he joined them with every intention of leading them inland. Somebody betrayed him to Pedriarias, and before they could set off, the governor sent troops and had them all arrested. A furious Pedriarias ordered Balboa to be locked within a wooden cage. Balboa’s future was looking pretty bleak.

0

Like

Published at 8:25 AM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 8:25 AM Comments (0)

In a pickle

Thursday, August 17, 2023

This story begins in 1509 with the discovery of a stowaway and his dog hiding in a barrel that had been loaded onto a ship sailing from Santo Domingo in Hispaniola to San Sebastian in Nueva Andalusia in the Caribbean. The stowaway and his dog were brought before the commander of the ship, Martín Fernández de Enciso, who demanded their names. The 34 year-old stowaway gave his name as Vasco Núñez de Balboa and that his dog was named Leoncico. Further questioning revealed that both were running away from creditors in Santo Domingo.

Unimpressed with these two scoundrels, Enciso ordered that they be marooned on the first uninhabited Island that they passed. However, over the next couple of days the crew took a shine to Vasco and Leoncico and begged the commander to reconsider his harsh sentence. Furthermore, the prisoner had revealed that he had knowledge that may help him with his mission.

The King of Spain, Ferdinand II, began an initiative to explore and colonise the mainland known then as Tierra Firme. In 1508 he ordered the establishment of two provinces with their border in the Golfo de Urabá; Nueva Andalucía to the east governed by Alonso de Ojeda, and Veragua to the west governed by Diego de Nicuesa.

Enciso was Alcalde of Nueva Andalucía, and he was leading a rescue mission to go to the aid of a stranded group of settlers who had been surrounded by hostile natives. He had been sent by his superior officer, Alonso de Ojeda, who had founded the colony of San Sebastián de Urabá. Ojeda had landed with a force of 70 men to establish a fortified base on the new continent but had been forced to abandon them after being injured in the leg by a poisoned arrow. When he reached Hispaniola he immediately ordered a rescue mission carrying more armed men and much needed supplies. He left the highest ranking soldier in command of the colony; a man by the name of Francisco Pizarro. (Yes, the very same Pizarro who conquered the Incas 24 years later.) Pizarro’s instructions were to hold out for 50 days, after which he was to abandon the settlement and use all possible means to get back to Hispaniola.

Vasco Núñez de Balboa Vasco Núñez de Balboa

When Enciso had Balboa brought before him again, the full story of Balboa’s past was revealed. He had sailed with Juan de la Cosa, on Rodrigo de Bastidas’ expedition eight years earlier. The expedition had landed just east of Panama and they began to map and explore the coast. Bastidas had been granted a licence to gather treasure for the crown under the established policy of quinto real, which required that the expedition to give the crown 20% of everything they found. Before it returned to Hispaniola the expedition had explored the coast from Panama, through the Gulf of Urabá to the Cabo de la Vela, which is the northern coast of present-day Columbia.

After the expedition, Balboa stayed in Hispaniola and bought a plantation and pig farm. This turned out to be a disaster for him, hence the escape from his creditors. Realising that Balboa had more knowledge of the coastline and the natives than any of his existing crew he promptly enlisted him as a guide.

When they reached the settlement it was to find that the natives had surrounded the remaining men and Pizarro was preparing to leave. After several attacks by the natives, Balboa suggested that they abandon San Sebastián and move south to Darién in the Golfo de Urabá where he knew there would be more chance of establishing a successful colony. The crew backed Balboa and Enciso withdrew the whole colony and its military contingent south to Darién.

Vasco Núñez de Balboa is really only remembered for two things. Establishing the first colony on the new continent was one of them.

It was not long before Balboa encountered opposition to his staggering rise from vagabond to governor of a colony. Diego de Nicuesa was the governor of Veragua as chosen by the King of Spain. He had also tried to establish a colony at Nombre de Dios further west on the Panamá isthmus. He also had met fierce resistance from the natives, and at this moment was fighting for his life after being badly wounded in an attack. A rescue party had been sent to search for the settlement, but they heard about Santa María and stopped there for information. The rescue fleet was commanded by Rodrigo Enrique de Colmenares, and when he realised that the settlement was in Veragua he persuaded the settlers that they should submit to being governed by Nicuesa and to reject the current junta. He appointed two representatives, Diego de Albites and Diego del Corral, and put them in charge of the colony and went to look for Nicuesa.

He found Governor Nicuesa in the nick of time before he and his men were overrun and killed by the natives. On the voyage back, he was told about Balboa and Santa María. What especially irked him was that Santa María was becoming very prosperous and, considering its situation, was well governed and stable. Seeing Balboa as a challenge to his authority, Nicuesa vowed to have Balboa removed.

However, back in Santa Maria, some of the settlers were unhappy that they were going to be ruled by Nicuesa, who had a reputation for being cruel, greedy and corrupt. This bleak assessment of their future governor was actively spread by a man called Lope de Olano and others, all of whom were jailed for their subversive activities. With the new junta rounding up anybody who disagreed with them it did not take long for the settlers to decide that Balboa was a better option. When the rescue fleet arrived at Santa Maria carrying Nicuesa a mob was ready to meet them on the quayside. Nicuesa pleaded to be allowed to come ashore as a soldier, not as governor, the mob refused. They forced him and 17 of his supporters to board an old, unseaworthy boat, gave them meagre supplies and forced them to leave port. They were never seen again.

That was March 1, 1511. The same week Balboa became governor of Veragua.

I am not sure that Balboa realised what he was doing, or just didn’t care. He was on a roll. He had just deposed the two governors that the King of Spain had appointed to control the exploration of a whole new continent of unknown, but clearly huge size, and set himself up as sole governor. The distance from Cabo de la Vela to Cabo Gracias a Dios was greater than the whole of Spain measured corner to corner. Did he not think that the King of Spain might have something to say about his conduct?

The first of his next two moves was sheer hypocrisy followed by unbelievable audacity. He put put Fernández de Enciso on trial for usurping the authority of the governor of Nueva Andalucía. Enciso was found guilty and sentenced to prison and his possessions were confiscated. Balboa let him think about his situation for a while and then offered to release him provided he go straight to Hispaniola and inform the colonial authorities of his new status and ask for more men and supplies to continue with the conquest of Veragua. From Hispaniola, Enciso had to promise to return to Spain.

Whilst he waited for a reply from Hispaniola, he continued his explorations inland through some of the most inhospitable jungle in the world. He followed and mapped rivers using native canoes and native guides. Some of the tribes were not hostile to the Spaniards, though some were and those who fought him he overpowered and enslaved. He seemed to prefer diplomacy and negotiation to outright war, and this carrot and stick approach paid off. Meanwhile, his experience as a farmer (failed) on Hispaniola came into play, and he and the settlers cleared the jungle and successfully planted and harvested corn. This eased their re-supply problem considerably. He successfully put down rebellions within his own ranks, and after the first year had earned respect from the settlers and Indians alike.

Balboa had achieved what the other two governors that the king sent could not, and this surely counted in his favour. He was also amassing quantities of gold taken from the natives, sometimes by force and sometimes in trade. This might have been a bigger inducement for the king to let him have his head.

There was a less tolerant side to Balboa though. On one of his trips he encountered a group of native men living apart from the normal villagers and in this land that was free of the iron control of any religious mores, societies were much more free and tolerant. Homosexuality was nothing new. Indeed, during some of the longer voyages at sea there were often private arrangements within the crews. But seeing an entire village without women disturbed Balboa to the extent that he turned his hunting dogs on all 40 inhabitants and killed them all. This is an example of extreme intolerant brutality not seen since the initial discovery of the Caribbean Islands by Columbus. His blatant hypocrisy shows in the self-flattering letters that he sent to the King of Spain explaining that he sometimes to act as a conciliatory force during his explorations and encounters with the natives.

His more stick than carrot diplomacy might have paid off, because over the next two years his expeditions met with outstanding successes and would lead the event that he is most famous for.

3

Like

Published at 8:49 AM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 8:49 AM Comments (0)

A heir at any cost

Friday, December 2, 2022

Isabel of Castile’s youngest daughter, Catherine, was betrothed to Arthur, the Prince of Wales, the son and heir of Henry VII of England. The marriage had been arranged when Arthur was only three and Catharine two. It was a high-profile agreement between two nations designed to cement an alliance between Spain and England against France. The Treaty of Medina del Campo was a bold plan by Henry II Tudor, who had ousted the Plantagenet line at the Battle of Bosworth Field, and was worried about the many more rightful claimers to the throne of England still alive. Of the twenty six clauses in the treaty, seventeen covered economic trading deals and military agreements, only one was about the marriage, the rest were negotiated rights following the wedding. Catherine’s dowry was fixed at 200,000 crowns (Over £5 million pounds in present day values.) and both parties happily signed the contract. After this, things started to become more than a little silly.

Cathrine of Aragon. Cathrine of Aragon.

Arthur’s father was a great believer in the legend of King Arthur of the round table, and at that time legend had it that Worcester was where the fabled court of Camelot had been. He built a manor house there, and took his wife to have his child there, so that his son would be born in the same place that King Arthur ruled from. When she had a boy, Henry was overjoyed and called his son Arthur in anticipation of a golden future ahead for the child.

Arthur Arthur

Before the children were of age a request was sent to the Pope for a dispensation to marry them even though they had never met, and were still far too young to be considered a husband and wife. The Pope duly sent his blessing and they were married by proxy in 1497 at Arthur's home, Tickenhill Manor near Worcester. Eleven year old Arthur was reported to have said to Roderigo de Puebla, the Spanish proxy for Catherine that “He much rejoiced to contract the marriage because of his deep and sincere love for the Princess.”

The young couple wrote to each other in the common language of Latin for four years until on the 20th September 1501 they were deemed old enough to live together. Arthur was 15 and Catherine was 14. Catherine arrived at Plymouth on the 2nd of October and a month later, the children met each other for the first time at Dogmersfield in Hampshire, and immediately discovered that they had been taught different forms of Latin and could not understand each other. Despite this setback, they eventually rode to London to be married.

On 14 November 1501, the marriage ceremony finally took place at Saint Paul's Cathedral; both Arthur and Catherine wore white satin and the ceremony was conducted by Henry Deane, Archbishop of Canterbury, assisted by William Warham, Bishop of London. Following the ceremony, Arthur and Catherine left the Cathedral and headed for Baynard's Castle, where they were entertained by "the best voiced children of the King's chapel, who sang right sweetly with quaint harmony."

Arthur’s mother, Margaret Beaufort, was a party to the next bout of insanity when Catherine was led away from the feast and undressed by her ladies-in-waiting. They veiled her and placed her in the nuptial bed, which had been sprinkled with holy water beforehand. Arthur was led in escorted by his gentlemen friends, to the accompaniment of viols and tabors, with no less a dignitary than the Bishop of London, who blessed the bed then led everybody from the room. In royal weddings, this was a not uncommon thing but this was probably the only public bedding recorded in Britain during the sixteenth century. Needless to say, the marriage was not consummated that night.

The following morning, the poor boy had to brag to all the courtiers of his prowess in bed. Whether the marriage was eventually consummated can only be known by the royal family, and later events would make the falsification of Catherine’s virginity highly desirable. The couple took up residence in Ludlow Castle in Shropshire where they both fell ill with the sweating sickness, a contagious disease that first appeared in 1485 and spread throughout England and Europe. The symptoms appeared rapidly and often caused death within hours. It effected rural areas the worst, and unlike other epidemics, spiked quickly before disappearing. Catherine survived the chills, body pains debilitating weakness and fever, but Arthur did not. He died on April 2 1502.

With his carefully laid plans in disarray, a heartbroken Henry VII now had to pass his title on to his second son, also named Henry. However, the trade treaty with Spain that a marriage to Catherine would bring was too important to lose. Catherine was now 17, but Prince Henry was only 11 years-old. To continue with the lunacy seemed reasonable, so Catherine was betrothed to little Henry. Catherine would need to be still a virgin in order to be married again, and she always claimed that she was. Isabel and Ferdinand were more than a little dubious of the marriage arrangements, but they feared the French, and an alliance with England was much desired, and so, the betrothal of Henry and Catherine went ahead.

Isabel knew all about the onerous duties of royalty from her own experience, and she had given Catherine advice and guidance. The two women corresponded continuously, but the loss of Juan had drained Isabel’s spirit. The constant wheeling and dealing with the fate of her family must have been a strain over the years and in November 1504, Queen Isabel died. She never saw Catherine crowned Queen of England, but for a while her other daughter, Joanna, became Queen of Castile with King Ferdinand as Governor and Administrator. Ferdinand was occupied with the growing discoveries and trade and with the new colonies in the Caribbean, and in April 1505 Columbus docked in Sanlúcar from his fourth and final voyage to discover that his patron was gone and he would have to deal with King Ferdinand or the unstable Joanna. He was still owed considerable money under the terms of his 1492 agreement, and he and his family were to sue the crown for payment for years to come.

Ferdinand married again to Germaine of Foix in March 1506 in the city of Valladolid where he had established his court, and a by now terminally ill Columbus followed him there on the back of a mule to continue with his demands. On 20 May 1506 Christopher Columbus died. In fourteen years he had transformed the world. But Queen Isabel’s legacy of change and expansion was still to be fulfilled, and so was Columbus’ belief in a westward route to China.

In 1509, five years after the death of Isabel, Henry VII died and Prince Henry became King Henry VIII, and the English crown was secure again. Twenty-five years-old Catherine married 19 years-old Henry. On June 15 of the same year, Catherine was crowned Queen of England alongside Henry in an extravagant joint coronation ceremony at Westminster Abbey. On their nuptial night Catherine discovered that Henry was nothing like his brother. Henry thought the now slightly plump Catherine was the most beautiful thing he had ever seen. His ardour was unquenchable. Not unexpectedly, she was pregnant within a few weeks.

Bad luck dogged Catherine all her life. She was a noble queen and a loving wife, but she failed to give Henry the one thing he needed most. Her first child, a girl, was stillborn on Jan 31, 1510. She kept the almost painless birth a secret because Catherine’s abdomen was still large, and it was thought that there was another child within her. Henry knew, of course, and he and Catherine’s two ladies in waiting were sworn to secrecy. Finally, as her abdomen returned to normal, it was realised that there was no other child. Catherine’s confessor, Frey Diego, wrote to her father, King Ferdinand, the following May to tell him of the loss. There would be other pregnancies, but the only child to survive was a girl called Mary who was born on February 8, 1516. She would fight similar battles to her grandmother’s on English soil to claim her birthright as the Queen of England, but bad luck followed Mary as it did her mother, and her womb refused to produce a male child when she married Philip II of Spain. Had it done so, England would have returned to being a Catholic country and become a part of the greatest empire the world had ever seen, and Mary’s step-sister, Elizabeth, would never have become queen of England; how this would have affected world history is incalculable.

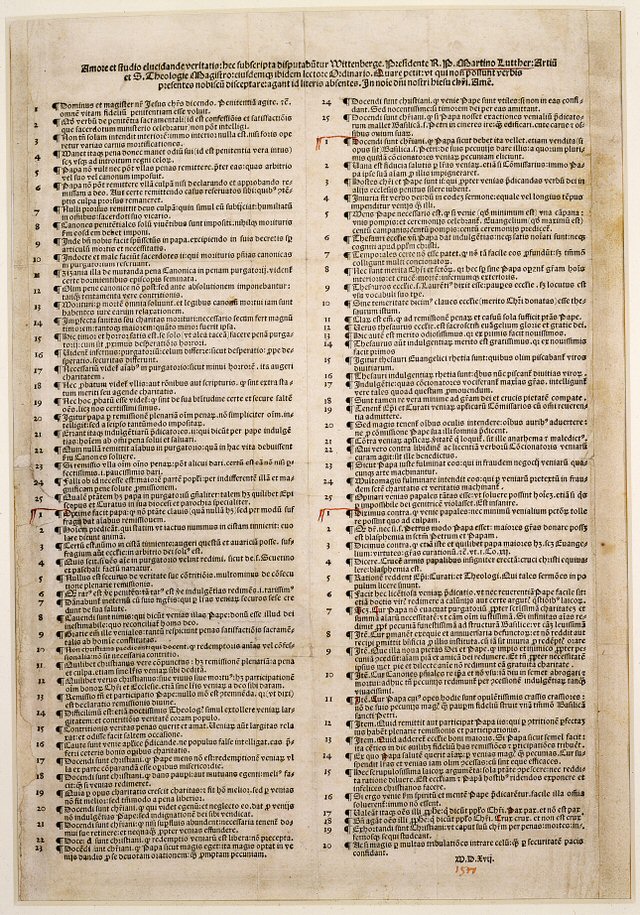

Catherine’s inability to produce a male child would bring a catastrophic change to England and the death of thousands. The genesis of this calamity lay in the hands of a German priest who was ordained in 1507. He became disillusioned with the Catholic Church and ten years later he nailed his proposals for its reform on the church door at All Saint’s Church along with several other churches around Wittenburg. (This was an accepted way of inviting discussion within the church.)

The 95 theses of Lutherian reform. The 95 theses of Lutherian reform.

He also published a sermon in German that all could read. At this time, the first printing presses were being used for posters and books, and Luther had his thoughts printed for publication. The sermon he printed can be read aloud in ten minutes, but it became a best seller with sixty thousand copies sold all over Christendom.

Luter pinning his thesis to the church door. Unknown artist.

The Church was furious, and Pope Leo X and the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, excommunicated Luther. He was escorted out of town, but friends intercepted the carriage, and he was spirited away to safety. By 1522, and still in hiding, Luther had translated the Bible into everyday German from Hebrew and Greek making it more accessible to the laity.

Henry VIII had been told about Luther’s bible and he was prompted to denounce it and back the Pope. Henry wrote his own book and had it published in which he re-affirmed the seven sacraments, or seven stages of the soul through life to heaven. The Pope was so pleased with Henry’s devotion that he granted him the title “Defender of the Faith,” a title which all British Kings or Queens still carry.

The printed works of Luther and Tyndale were being shipped clandestinely into England and Cardinal Wolsey ordered their collection and burning before the doors to the old St. Pauls Cathedral. The power of the Catholic Church in England was being undermined by the reproduction of a bible that all men could read. The clergy knew that real danger was that everybody could see that the Catholic Church had been distorting the true meaning of the faith for centuries.

Henry had been casting a roving eye around his court, and had his choice of young girls. Early that year, a young girl of 15 years came to take up a post as maid of honour waiting on his wife. Anne had a striking beauty and her sophisticated manners earned her many admirers at court. Although she resisted Henry VIII's advances, by 1533 Anne was pregnant to Henry. This is just what Henry had been waiting for. He appealed to Pope Clement VII for an annulment to his marriage to Catherine so that he could marry Anne. The Pope was afraid to go against the will of Catherine's nephew, Charles V, The Holy Roman Emperor, and refused his plea.

When she came to Henry’s court, Anne brought with her a book written and published in Antwerp by William Tyndale entitled “The Obedience of a Christen man, and how Christen rulers ought to govern.” Henry had condemned Tyndale and his Bible, but here was his pretty lover with a book that told Henry that Kings were accountable only to God and not the Pope. She had underlined the passages that she wanted Henry to read. When he had finished, he remarked that “This Book is for me and all kings to read.” Henry had seen the lesson in Leviticus. “And if a man shall take his brother's wife, it is an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother's nakedness; they shall be childless.” He believed that by marrying his brother’s wife, Catherine, he had cursed himself to childlessness.

Catherine pleaded with Henry not to divorce her, saying that her marriage to his brother had never been consummated. With Anne pregnant with a possible male heir, Henry was backed into a corner. He made his decision and broke with the Catholic Church. He passed the Act of Supremacy, declaring that he was the head of the English Church and appointed Thomas Cranmer as Archbishop of Canterbury, who immediately annulled the marriage between Catherine and Henry and announced the wedding of Ann and Henry. In June 1533 Anne was crowned Queen of England in a lavish ceremony at Westminster.

The dynasty of Queen Isabel was not over yet, and already the religious world had been split down the middle, but the next century would see that her joining of León, Castile and Aragon into one kingdom would eventually raise Spain to superpower status.

0

Like

Published at 10:54 AM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 10:54 AM Comments (0)

The fight to be Queen of Castile

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Enrique, king of … well, nothing, flew into a rage when he heard about the marriage of Isabel and Ferdinand. His seedy and devious advisors, chief of whom was Juan Pacheco, the Marquis of Villena, put Joanna forward as the rightful heir to the crown. In a breathtaking betrayal, the Archbishop of Toledo left Isabel’s court to unite with his great-nephew, Juan Pacheco, to support him with his claim. This foul crew were even more enraged when Isabel gave birth to a girl, whom she named Isabella after her mother, just over eleven months after the marriage. (2 Oct 1470) To the delight of the nobles of Castile, this was a much better alternative to the embarrassing Beltraneja who Enrique was proposing as heir. Tensions rose within the kingdom, and to defuse this situation, Isabel and Ferdinand met with Enrique to discuss matters in order to give him some measure of respect and reassurance of his royal lineage.

(So far, this account has seen at least two mysterious deaths and one suspected poisoning, but the twist that wins the prize happens now.)

Shortly after the meeting with Isabel and Ferdinand, on the 1st October 1474, the thorn in everybody’s side, Juan Pacheco, died suddenly in Trujillo. His son, Diego, ingratiated himself with King Enrique and stepped into his dead father’s shoes, but six weeks after Pacheco died, King Enrique died on 11 December 1474, and on the 13th December 1474, Isabel was crowned undisputed Queen of Castile.

You would think that this would be the end of Isabel’s worries, but no.

Diego Pacheco, backed by the Archbishop of Toledo, invited King Afonso V of Portugal (43 year-old uncle of Joanna) to marry the 13 year-old and invade Castile to take the throne from Isabel. Alfonso’s first wife had died in 1455, and to the king, this seemed like a reasonable offer at the time.

In May 1475, the Portuguese army crossed into Spain and advanced to Plasencia. Here Afonso married Joanna and began his campaign to take the Castilian crown. The war raged back and forth for almost a year until 1 March 1476, when the Battle of Toro took place, a battle in which both sides claimed victory, but neither won.

The armies fought each other to a standstill, and King Afonso was forced to retreat and regroup his forces. Ferdinand showed his genius by sending messengers out to all the cities of Castile and the nearby kingdoms that he had crushed the Portuguese in a great military victory. Overnight, support for Joanna collapsed.

To capitalise on the victory, Isabel convoked courts in Segovia in 1476, where her eldest child, Isabella was proclaimed as heiress to the crown of Castile, thus legitimising and strengthening her own claim to the throne. Later the same year, inspired by her husband’s successes in battle, Isabel led an army against an uprising in Segovia while Ferdinand was fighting elsewhere. She successfully negotiated a peace deal with the rebels, much to the surprise of her military advisors. The nobles of the kingdoms were watching events, and they realised that Isabel was becoming a force to be reckoned with.

He had to defuse this dispute to ensure Christian stability in a Europe that was beset in the east a new order. Several diverse principalities of Anatolia had unified by 1453 to become the Ottoman Empire, and led by Mehmed the Conqueror, had ended the old Roman Byzantine Empire by taking Constantinople in 1454, and then advancing into Europe by taking the Balkans. They had closed all trade routes by sea and land to the orient. This represented a huge financial loss to all Christendom and a threat to the Catholic Church.

This is where the wheeling and dealing started.

Pope Sixtus IV now stepped in to end the dispute over Castilian succession. To avoid further bloodshed and more costly wars, Isabel and Ferdinand were urged to sign a treaty with King Afonso and his son, Prince John of Portugal. The involvement of one of his bishops in the double-dealing between kingdoms, to say nothing of the forging of papal signatures, must have angered him more than a little.

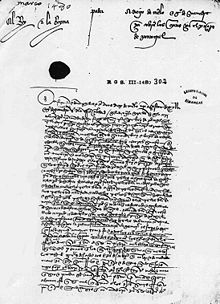

The treaty of Alcáçovas The treaty of Alcáçovas

The treaty that the pope offered had five parts:

The first part was an agreement by both sides to abandon all claims on each other’s thrones.

The second part was to grant Portugal exclusive rights to all Atlantic trade.

The third part was about the fate of Joanna, who had been an innocent pawn in all of this. The pope annulled her marriage with King Afonso on the grounds that she was too closely related to him, (consanguinity) and rendered her ineligible for either crown.

The forth part was a contract to marry Isabel’s daughter, Isabella, to Afonso, the son of Prince John of Portugal.

The final part was to pardon all the Castilian supporters of Joanna.

The Treaty of Alcáçovas, as it became known, was signed by both sides on September 4, 1479.

It was not a very fair treaty as far as Castile was concerned, but Isabel and Ferdinand were backed into a corner. Granting Portugal the exclusive right of navigation and commerce in all of the Atlantic Ocean south of the Canary Islands meant that España was practically blocked out of the Atlantic and deprived of any share in the gold of Guinea. This created unrest among Andalusia’s nobles, who feared that they had bought peace at too high a price and had restricted their expansion into the Atlantic.

It was not all loss to the Catholic family, on 30 June 1478 Isabel further secured her place as ruler with the birth of her son, John, Prince of Asturias, and in 1479, Ferdinand’s father died and he became King of Aragon joining the kingdoms of Aragon, Castile and León into a united country.

Meanwhile, law and order had broken down in the kingdoms, and robber bands made normal trade and commerce difficult. Isabel and Ferdinand created a militia whose sole purpose was to police their kingdoms and eliminate the bandits. She gradually gained more control of the economy, and stability returned, but España was desperately poor.

With Atlantic maritime trade thwarted by Portugal, and Mediterranean trade with the east blocked by the Ottoman Empire, Isabel turned her eyes to the south, where a large part of Iberia was still ruled by the Moors whose caliph Muhammad XII oversaw rich farmlands from his capitol in Granada. They had gold and jewels in abundance, and were probably still trading with the east.

In 750, the Galicians had been the first to force the occupying Muslims from their lands in the northernmost tip of Iberia, and the Reconquista had been raging ever since. The first crusade was started on November 27, 1095 by Pope Urban II when he gave a sermon outside the Cathedral at Clermont, Auvergne, urging the nobles to unite and liberate Jerusalem. The Holy wars were in reality organised raids to collect as much booty as the Christian invaders could take from the Moors. A noble religious cause was just a good excuse for daylight armed robbery. This had been going on for 729 years when Isabel began planning the final campaign to drive the Moors from Iberia.

It took twelve years, with Christian troops advancing a little more each year. During this campaign Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba rose to prominence and became Isabel’s most trusted general. A masterful strategist and tactician, Córdoba constantly refined the army of España, gaining himself the unofficial title of El Gran Capitan. His training brought the troops under his command to a new level of efficacy not seen since Roman times. He trained his men in the use of pikes as a defence against the dreaded jinetes, the much feared Moorish cavalry, and he was one of the first Europeans to introduce specialised regiments trained in the use firearms onto the battlefield. His visionary training made the Spanish army the dominant force in Europe for more than a century and a half. Isabel rewarded him by making him Duke of Santiángelo in 1497.

But it was in the final capitulation of the Moors at the Alhambra palace in Granada in 1492 that brought Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba to the forefront. It was he who negotiated the final surrender terms with Caliph Muhammad. Gonzalo spoke Arabic fluently and was highly respected by both sides as an honourable man who would deal fairly with the Moors. King Ferdinand had little respect for the outgoing Moors and as soon as he entered the palace he removed everything of value. But the greatest treasure of Moorish civilisation was in their philosophy, medicine and science, and this was to be found in the libraries which were abandoned when they left. Ferdinand made a show of emptying the libraries and publicly burning all the books.

Worse was to follow. Intolerance of anything Islamic had begun to grow into intolerance of anything not Catholic. Tens of thousands of Moors had been forced to convert to Catholicism during the reconquest though many had retained their Islamic faith and worked in society as doctors, lawyers and artisans. So had the Jews, but posters began to appear depicting Jews as necromancers with dark and evil rituals and a cancer was growing that the conversos were untrustworthy and secretly worshiping their own prophets. As early as 1478, while Ferdinand and Isabella were still consolidating their kingdom, they made formal application to the Pope for a tribunal of the Inquisition in Castile to investigate these and other suspicions. Moors and Jews had never had full equal rights within Christian lands and were taxed more than their Christian counterparts. This culminated in the Alhambra decree of 1492 issued by Isabel and Ferdinand requiring that all Jews convert to Catholicism or leave España. This edict would later be watered down in its severity, but for the Jews in España it was catastrophic, and the enforcement of the edict by over-zealous officials and the inflamed racist mobs who persecuted the Jews was close to genocide. All their possessions were seized and they were only allowed to take the clothes they stood in as they fled en mass. However, the booty collected was added to the almost empty coffers of the kingdom drained by ten years of constant warfare and the battles with her half-brother over the crown.

The gamble that she took to finance Columbus’ insane theory was small fry to the gambles that she was taking with the newly formed and victorious nation of España, but even though it brought huge dividends, it also brought the jealousy of King Manuel I of Portugal.

King Manuel I of Portugal. King Manuel I of Portugal.

Isabel was acutely aware that she needed to cement trading ties with other countries, and her growing family was to be instrumental in securing an income for España. The Treaty of Alcáçovas obliged Isabel to marry her daughter, Isabella, to King Manuel of Portugal and Isabella became Queen of Portugal at the age of 27 in September 1497, but she only reigned as queen for a year before she died. Portugal had always been Castile’s rich neighbour and a family bond with King Manuel was crucial, so Isabel betrothed her third daughter, 15 years-old Maria, to be married to King Manuel to replace Isabella. It seems callous now, but to keep her country solvent, she needed peace, and time to make other connections.

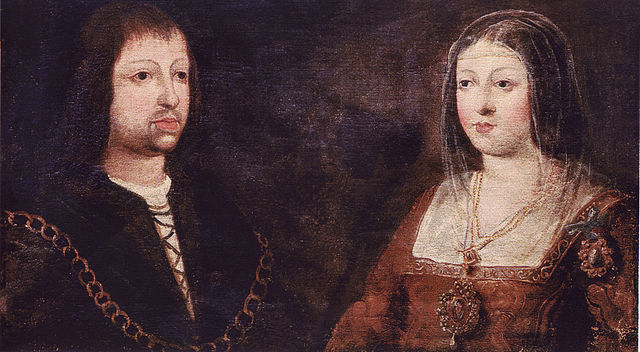

Los Reys Catholicos, Museo del Prado.

Isabel’s pride and joy was her son Juan, who was to be her heir to the throne. He was married to the Archduchess Margaret of Austria, but tragedy struck when he became ill and died at the age of 19 in 1497 leaving no heir. Isabel took his death badly and never really recovered her spirit; her health began to deteriorate. That left Juanna, who became the female heir at the age of 18 and who was dutifully married to Philip the Handsome. From her infancy Juanna had been a problem child. She was given to tantrums and irrational behaviour that caused her mother, not the most tolerant of women, to use sometimes draconian methods to control her. However, once married, Isabel hoped that she would be somebody else’s problem. She was wrong.