This cup runneth over.

Friday, July 30, 2021

There are two cups in existence that claim to be the Holy Grail. One is in the Cathedral of Valencia and the other is in the Cathedral of Genoa. There is a third contender, The Chalice of Doña Urraca in León, but this is a doubtful latecomer, and owes its claim to authenticity to a book written in 2014.

So much has been written, and by so many, about the cup that Christ used at the Last Supper that the Holy Grail has become a metaphor for something so precious and unattainable as to be other worldly. There is no doubt Jesus used a cup at that famous meal, and it is mentioned by Mark and Luke and by the Apostle Paul in Corinthians, but the cup had no significance to the writers of the gospels; it was just a prop that Jesus used to explain his message to them. Matthew writes that Jesus said:

“Drink this, all of you; for this is My blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine until I drink it new with you in My Father’s kingdom.”

Over the centuries within the Catholic Church, the search for icons from Christ’s life became a holy quest all by itself. Just about every European cathedral has an icon; a piece of the cross, the hair of a saint or one of his bones. Having an icon became a way of getting one up on a rival bishop or neighbouring medieval city. Fake icons abound, and the fertile imagination of writers and romancers have fed the fevered minds of the faithful. The next time the cup appears in written records is sometime around the year 380, when St. John Chrysostom was commenting on Matthew’s account of the Last Supper. He says,

“The table was not of silver, the chalice was not of gold in which Christ gave His blood to His disciples to drink, and yet everything there was precious and truly fit to inspire awe.” Although 350 years after the event, his comments showed a growing awareness of the religious significance of the cup that Jesus used that night.

The first mention of the existence of an actual cup comes 190 years later in 570 from Antoninus of Piacenza, who wrote a travelogue of the holy places in Jerusalem which said that he saw “the cup of onyx, which our Lord blessed at the last supper.” He saw it in the Basilica built by Constantine close to Golgotha and the Tomb of Christ where it was displayed with other relics of Christ’s time.

But the legend of the fabulous Holy Grail with miraculous powers begins during the 1180’s, when Chrétien de Troyes wrote a romance for his patron, Philip I, Count of Flanders. (Romances were high-culture poetic narratives of chivalric heroism with the emphasis on love and courtly manners.) The poem was written in Old French and the grail appears in the unfinished fifth verse of Perceval ou le Conte du Graal. Philip provided Chrétien de Troyes with the original storyline, but died in 1191 while crusading at Acre in the Holy Land. The romance was about the adventures of a young knight, Perceval, who joins King Arthur’s court and gains distinction for bravery. During his travels he is invited to eat with the mysterious Fisher King, and one of the king’s serving girls carries a graal. In the morning, Perceval awakes alone and continues his journey. A young girl whom he meets that same morning admonishes Perceval for not asking the Fisher King about the graal and its significance.

Perceval arrives at the Grail Castle to be greeted by the Fisher King in an illustration for a 1330 manuscript. Source: Wikipedia.

The story now breaks off to follow Gawain, a favourite of King Arthur, in a new chapter which was also never finished. The reason that these works were left unfinished is assumed to be either the death of Philip or Chrétien de Troyes, but other writers soon jumped in to finish the epic poem. Before the turn of the 11th century, Robert de Boron wrote two poems, Joseph d'Arimathie in which the grail is used by Joseph of Arimathea to catch the blood of Christ at the crucifixion, and Merlin; the latter work survives only in fragments rendered in prose and written around 1210, possibly by Robert himself. Both were later translated into Middle English by Henry Lovelich in the mid-15th century. The two poems are thought to have been combined to form either a trilogy – with the Perceval verses forming the third part – or a tetralogy with the inclusion of the Lancelot-Grail stories leading to the Le Morte d'Arthur. (Death of Arthur) All of these romances were hugely popular in the middle ages. The writers had set the stage, and all that was required now was the star of the show; the Holy Grail itself.

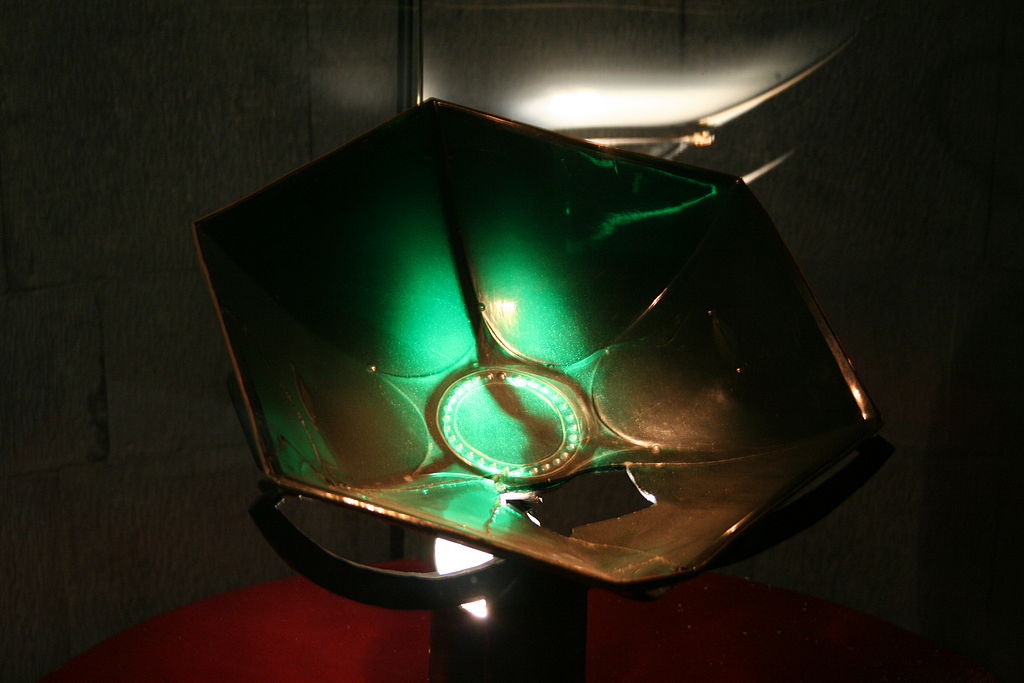

The Grail of Valencia. Photo: Sylvain Billet.

The Holy Chalice of Valencia is an agate cup which has been enclosed in an ornate gold mount with handles so that the cup can be picked up without touching it. The cup itself was most likely made in a Palestinian or Egyptian workshop between the 4th century BC and the 1st century AD and its (alleged) history is the most-plausible of the two Grails. Seemingly, the cup was taken to Rome by St. Peter after the death of Christ, where it stayed in obscurity until Emperor Valerian began a witch-hunt against Christians in 258. Pope Sixtus II was forced to hide many of the sacred relics in far-flung places where the Romans could not find them. Pope Sixtus along with numerous bishops, priests, and deacons were put to death by Valerian.

Saint Lawrence in Huesca was the pope’s deacon in Spain, and the grail was delivered to him. That the pope removed the chalice from Rome is recorded in the Vatican records as “He took this glorious chalice”, and the phrasing of the translated passage indicates a high level of veneration for the grail. Alongside the Grail in the cathedral, written on vellum, is a list of items that the church had to divide up and hide amongst its members during the Roman persecution. Saint Lawrence is mentioned on this list, but another letter which accompanied this list and detailed the persecution by Valerian has been lost. A paper trail of documents concerning the grail leads us back as far as 1134, when it is mentioned in an inventory of the treasury of the monastery of San Juan de la Peña drawn up for the Canon of Zaragoza.

There is a more dubious alternative history for the Grail of Valencia, which is without the benefit any kind of proof. In this history the grail was acquired by a Roman soldier sometime during the third century and it was he who brought it back to his home in Huesca. When the Moors invaded in712 it was taken to San Juan de la Peña for safety. This is where the two histories join.

The grail was kept and venerated during many centuries among the relics of the Cathedral, but when Napoleon invaded in 1809 it was taken to Alicante, Ibiza and Palma de Mallorca. In 1916, it was finally housed in the old Chapter House, later called the Holy Chalice Chapel, but when Civil War broke out in Spain in 1936 it was again removed and hidden in Carlet.

The Vatican has never publicly said that the Grail of Valencia was the actual cup used by Christ. The nearest that the church will come to endorsing the grail is to say that it could possibly be the cup that Jesus used. Nevertheless, Pope John Paul II celebrated mass with the Holy Chalice in Valencia in November 1982, when he referred to the grail as “a witness to Christ's passage on earth”. In July 2006 Pope Benedict XVI also celebrated mass with the Holy Chalice calling it “this most famous chalice” paraphrasing words in the Roman Canon said to have been used by the first popes to refer to the Holy Grail before the 4th century in Rome.

The Sacro Catino, or The grail of Genoa.

The other Grail, or Sacro Catino, in Genoa is very different in shape to the one in Valencia. It’s not a cup but a hexagonal dish made of green Egyptian glass. It was brought to Genoa by Guglielmo Embriaco as part of the spoils from the conquest of Caesarea in 1101. Embriaco was a Genoese merchant and military leader who came to the assistance of the Crusader States in the aftermath of the First Crusade. Even though Embriaco would later be considered as one of the founders of The Republic of Genoa, the Genuese did not have much respect for him. His nickname amongst his own countrymen was William the drunkard, and during the campaign, which was finally successful, he acquired a second sobriquet of William the mallethead. Guglielmo accepted the grail because he was told that it was, “made of a single emerald” a precious stone thought to have miraculous powers. It was not considered to be a holy relic until after the widespread success of the grail romances and the amplification of the legend by Jacobus de Voragine in 1290 in his literary work, Chronicon.

When Napoleon invaded in 1805 he seized the bowl and took it to Paris where it was damaged, and the world found out that it was not made from emerald but glass. It was returned to Genoa in 1816 where its popularity is still as great as ever.

The Chalice of Doña Urraca The Chalice of Doña Urraca

The final Spanish grail is known as the Chalice of Doña Urraca and is kept in the Basilica of San Isidoro in León, Spain. It had never been considered as a Holy Chalice, and was only proposed as such in a 2014 book called Los Reyes del Grial. The book, which develops the hypothesis that this cup had been taken by Egyptian troops following the invasion of Jerusalem and the looting of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, then given by the Emir of Egypt to the Emir of Denia, who in the 11th century gave it to the Kings of León in order for them to spare his city in the Reconquista. Only the writer of the book claims that it is anything but an elaborately worked fake.

In the light of all the fabulous stories and romances written about the grail over the centuries, including all the modern books like Da Vinci Code and films like The Last Crusade, should we consider all the grails to be nothing more than elaborate fakes? The true story of the cup has been lost in all the fantasy and conspiracy generated by writers. I like to think that Indianna Jones has it right; when asked to choose the true true cup from all the bejewweled and golden chalices he spurns them and picks a simple cup as would be used by a carpenter.

3

Like

Published at 9:00 AM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 9:00 AM Comments (0)

You won't need a mask for this one

Friday, July 16, 2021

It is a quarter to ten on Saturday morning in the port of Lisbon and many people are arriving at the weekly market held in the plaza by the docks. Fish caught that morning and vegetables brought in from the farms will be on sale, along with fruit, dates and spices. The early risers will have already bought the best fish and are pushing through the noisy stalls looking for something to go with it for the evening meal. White linen canopies protect the stallholders and their goods from the warm morning sun, and children run between the shoppers calling to each other and laughing.

Suddenly the earth beneath the feet of the people moves so rapidly that they are thrown to the pavement. Stalls collapse, and fruit rolls amongst the people on the ground who are trying to scramble to their feet. Many have managed to stand only to have the earth move again in the opposite direction, and once more they tumble to the floor. So far this has been soundless apart from the screams and cries of the people, but now a rumble turns into a roar as the buildings around the plaza collapse upon the market stalls, burying them in masonry and rubble. It is All Saints day, and many of the houses and churches had lit candles, and as the buildings collapse, the flames of the still burning candles ignite spilt oil, which soon spreads to the bone-dry timbers of the fallen buildings and their furniture. The earth is still moving, and the next heave opens a fissure across the plaza three meters wide. Fruit and people roll into the chasm and those around the edges scramble away in terror as the earth continues to shake. For five minutes the earthquake continues before stopping. Now, the only sound is that of the wails of the injured and the screams of those who are terrified.

Many who fear more tremors push through the crowds, scrambling over the rubble and bodies, ignoring the cries of those who are trapped. They elbow their way to the open area of the docks and are amazed by what they see. The sea is leaving faster than any tide that they have ever seen. Wrecks and rocks never seen before appear as the sea retreats, and ships that had been riding at anchor are left high and dry and slowly roll over onto one side.

The fires in the rubble and remaining buildings are growing in intensity and more people run into to the open areas. Those on the seafront stand shocked and speechless at the spectacle of burning and collapsed houses as far as their eyes can see. But their attention is soon drawn to the seaward horizon by the low roar of the returning ocean. A tidal wave three meters high is rushing towards them, lifting ships and tossing them over as though they were toys. It crashes over the low seawalls and surges through the city. The water subsides, but the fire rages on creating a firestorm that draws the oxygen out of the air, suffocating hundreds of people before they can flee. More waves crash over the sea walls, but the fire is unstoppable and continues burning for weeks after the earthquake.

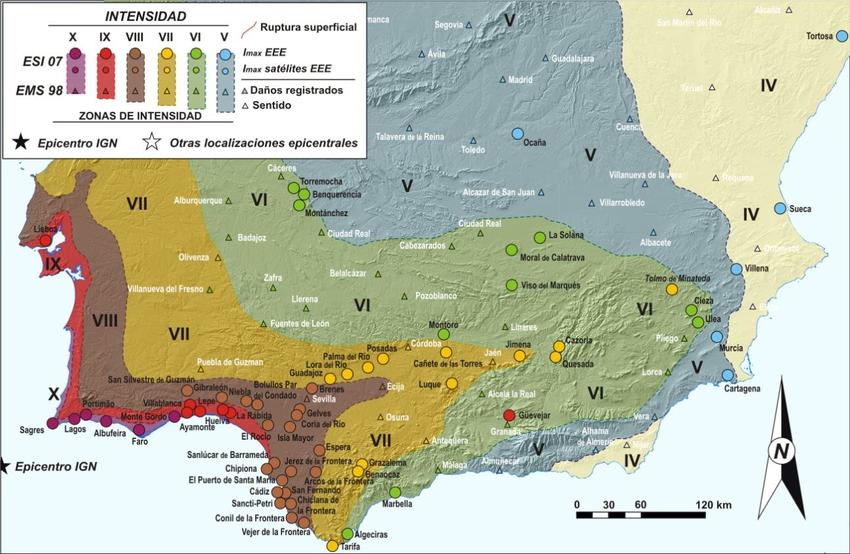

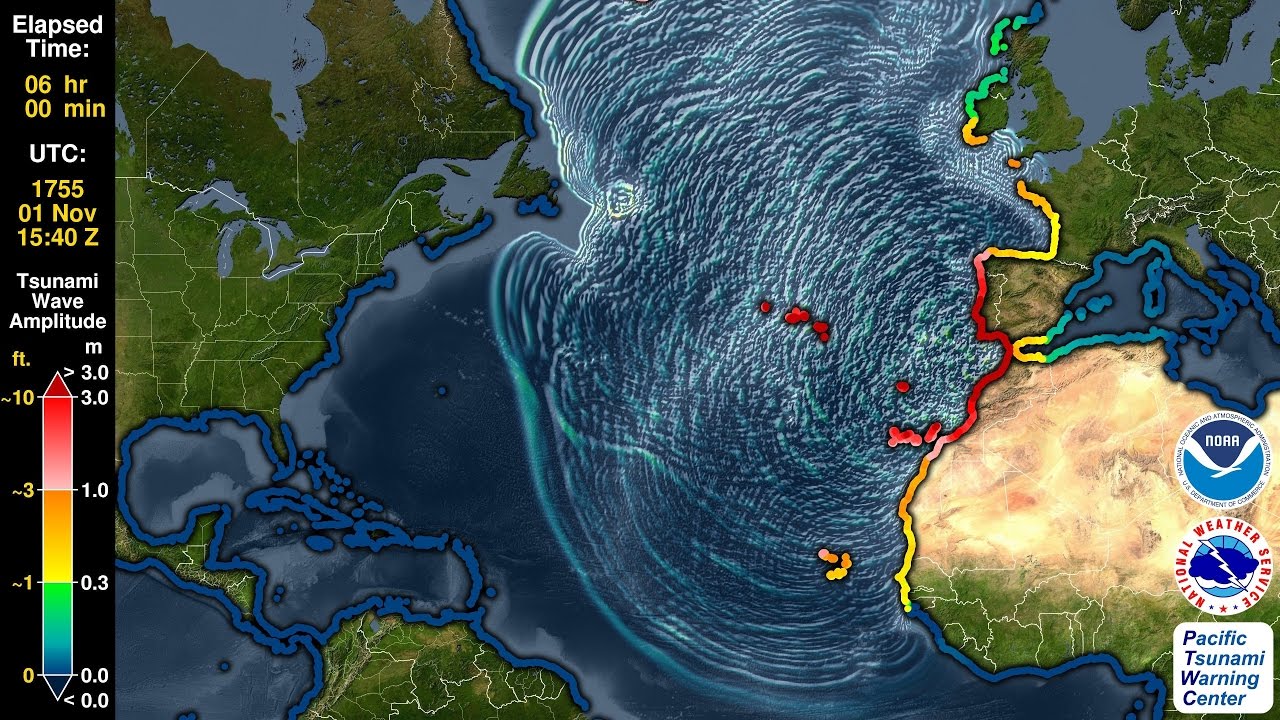

This was the Lisbon earthquake of 1577, and when the fires had burned themselves out it was estimated that between30,000 and 50,000 people had been killed; one fifth of the population of the city. Eighty five percent of the city’s buildings had been lost, along with priceless artworks and libraries. It was not just Lisbon that suffered; the western coasts of Andalucia and Morocco were devastated by tremors and the following tidal wave. Spain’s primary Atlantic port of Cádiz was almost totally destroyed as the tidal wave entered the port, became focused, and roared across the surrounding low-lying areas. The earthquake caused damage to buildings far inland, and the Alcazar in Seville was found to have cracks in its foundations which required major building repairs.

But the 1577 earthquake was not the only one. It was just the biggest and best documented one out of a known total of four. After the 1755 earthquake the Marquis of Pombal, the Portuguese Secretary of State for Internal Affairs, was given the job of rebuilding Lisbon and the Portuguese economy following the earthquake. In an effort to better understand his task, he asked one of his deputies to look through the records and see how previous governments had dealt with earthquakes. His search gave details of the earthquake that had occurred in the early morning of January 26, 1531, which had been preceded by two foreshocks on the 2 and 7. Again, damage to the port of Lisbon had been severe, with around one-third of the buildings in the city destroyed and 1,000 lives lost. Before 1577, earthquakes were believed to be “Ira Dei”- the wrath of God, but the investigations started by Pombal led to the birth of modern seismology and the understanding of earthquakes. In the end, the Marquis of Pombal rebuilt Lisbon hoping that it was over, but 184 years later disaster struck again.

On the afternoon on March 31, 1761 there was another earthquake causing widespread damage across Portugal, Spain and Morocco. Although not as strong as the 1577 earthquake, the effects of this one were felt throughout Western Europe as far north as Fort Augustus in Scotland, at the southern end of Loch Ness. There, fishermen noted a sudden two-foot high rise in the lake level which lasted just less than an hour before subsiding again. Simultaneously, Cork in Ireland recorded “strong shaking” that lasted several minutes.

The final link in the chain came in 1909, when a Portuguese newspaper reported the discovery of an unsigned manuscript of eyewitness accounts of an even earlier earthquake in 1321. This report was corroborated in 1919 by the discovery a four-page letter found in a Lisbon bookshop addressed to the Marquis of Tarifa describing the1321 event. It was clear now that the 1577 earthquake was the biggest, but only one of four earthquakes to shake Portugal and Spain. Earthquakes on this level of destruction seemed to have been occurring around every 200 years since records began.

Now, of course, we are in possession of much more information to help us understand what forces cause earthquakes. Off the coast of Spain, the Atlantic sea bed is relentlessly moving east at 3.8 mm a year, giving rise to a series of strike-slip and thrust faults collectively called the Azores-Gibraltar Fault. The epicentre of the 1577 earthquake was along a 50-kilometer fault some 200 kilometers south of Lisbon, The unstoppable eastward movement of the earth’s crust beneath the Atlantic makes it inevitable that there will be another earthquake like the one in 1577.

For Andalucia, the greatest risk to the population lies in the arc of coastline from Ayamonte in the north to Tarifa in the south. The earth tremors are likely to cause damage as far inland as Seville, but because of the low-lying nature of the coastline, the following tsunami presents the biggest threat to life. Areas of the coast that are substantially higher than sea level, and have cliffs facing the sea will be safe, but much of the coastline is low-lying with a high population density. Two main areas of this coastline have been designated as high risk from the tsunami. Huelva in the north, and the Cádiz bay area, including El Puerto Santa Maria, Chiclana, Sanlúcar de Barrameda and San Fernando.

Historical records and simulations have been combined to predict that the worst-case tsunami could be to be up to 7 meters high with a flow velocity of between 3 to 8 meters per second. If previous earthquakes are anything to go by, there may be several tsunamis after the earthquake, followed by more aftershocks.

Geologists have learned not to cry wolf too often. False alarms breed complacency which will get people killed when the real event arrives. The answer is to have regular drills and exercises so that everybody knows what to do, and it soon becomes apparent that time is the main factor in saving lives. Estimates vary on how long it will take for the tsunami to arrive after the earthquake. Huelva will be first to see the approaching wave and raise the alarm, but by the time that the warning reaches Cádiz and the alarms sounded the wave will be just 20 minutes away.

The Diario de Cádiz and the Vos de Cádiz have raised concerns that most of the population have no idea where nearest safe areas are, or what precautions to take. There is no recognised alarm system for people who work and live in these areas. They go on to say that every family should know where to go to be safe. Schoolchildren in Cádiz have regular drills in which they leave school and walk to the nearest high rise building when the alarm is given, but there is no plan for their parents or grandparents. An even greater worry, are the huge numbers of holidaymakers who fill the beaches every summer weekend. They will have no idea of how to go about the “vertical evacuation” that the gaditanos have planned.

The Junta de Andalucía and the Diputación y el Ayuntamiento de Cádiz have drawn up emergency procedures for medical, security and the restoration of infrastructure after the event, but they have little to say about what measures can be taken to save lives before the event. Some of the barrios have designated their own high-rise refuges, and neighbourhood committees in Cádiz have drawn up lists of basic measures that householders can follow. Immediate loss of electrical power, roads blocked by fallen buildings and the destruction of most vehicles is inevitable, so the storage of emergency first-aid supplies and large amounts of bottled water are a must. The medical, rescue and fire services will be stretched to the limit, and aiding the injured and homeless survivors will require mobilisation on a national scale.

In built up areas the buildings have been assessed for their survivability in a major earthquake. Overhangs, balconies, glass roofs and fasciae will go in the first few seconds. Conventional stone and mortar may not survive a prolonged earthquake, but steel-reinforced concrete buildings might, and if they are multiple-story, could become refuges from the tsunami. The risk of fire is a major problem. With most homes using bombonas for heating and cooking, the puncture or cutting of rubber tubes could release highly explosive and inflammable gasses into partially collapsed buildings and hinder rescue attempts even when the water has subsided. Equally, the storage sites for bombonas and the tanks of petrol and diesel beneath most gasolineras are the subject of much concern.

To make people aware of the danger of the tsunami, La Sexta have produced a virtual video of what can be expected in Cádiz. The only thing missing from the video is the thousands of people in the streets who were too late to get to the third floor and safety.

https://www.diariodecadiz.es/vivir_en_cadiz/Sexta-video-maremoto-Cadiz_0_1581744059.html

6

Like

Published at 11:42 AM Comments (4)

6

Like

Published at 11:42 AM Comments (4)

Painting at the Hard Rock Cafe

Friday, July 2, 2021

Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola was a Spanish jurist who owned lands around Santillana del Mar in Cantabria. He was also an amateur archaeologist, and when one of the local hunters, Modesto Cubillas, told him of a cave on his land his interest was piqued and he decided to go and look for himself. The cave had been known to local people for years, but Sautuola began a series of visits starting in 1875 during which he explored the cave system. On one of these visits his eight-year-old daughter, Maria, accompanied him, and it was she who first saw the shadowy form of pictures on the ceiling of the cave. She excitedly told her father who brought trestles on their next visit so that he could examine the ceiling more closely.

Maria Sans de Sautuola. Maria Sans de Sautuola.

He was amazed to find that the ceiling was covered in paintings of bison. Sautuola had seen similar images engraved on Paleolithic objects displayed at the World Exposition in Paris the year before, and he rightly assumed that the paintings might also date from the Stone Age. This prompted him to write to Juan Vilanova y Piera at the University of Madrid, who immediately travelled to Santillana del Mar to see the find for himself. During 1879 they explored the cave together and the following year published a scientific paper proposing that the paintings were Paleolithic in origin.

Sautuola´s drawing of the paintings.

They presented their paper at the 1880 Prehistorical Congress in Lisbon, but they met instant opposition from two French specialists on prehistoric art, Gabriel de Mortillet and Émile Cartailhac. Most of the known cave paintings in Europe at that time were in a small area alongside the river Dordogne, the most famous, of course, being Lascaux. The Frenchmen examined the cave for themselves, and at the congress they ridiculed the findings of Sautuola and Piera. Because they were de-facto the only experts in a very limited field, their opinion carried a lot of weight.

Cartailhac rejected the paper because of the high artistic quality of the Altamira paintings and their exceptional state of conservation. He called attention to the fact that there were no soot marks that would be unavoidable for a prehistoric painter who was using tallow lamps for illumination whilst painting a ceiling. To add to the condemnation of Sautuola and Piera’s paper, a fellow Spanish archaeologist accused Sautuola of paying an artist to paint the bison, and that the whole thing was a fraud. Sautuola, with his limited experience, could not defend the accusations, and it was only years later that he learned that many of the Paleolithic painters used marrow fat in their lamps because it doesn’t give off smoke or soot.

The damage was done, and Sautola’s find was ridiculed and rejected by mainstream archaeology. Sautuola died in 1888, but the science of archaeology moved on, and later finds at other sites corroborated his findings. In 1902 the scientific society retracted their opposition to the Spaniard’s paper. Cartailhac emphatically admitted his mistake in the famous article, “Mea culpa d'un sceptique” published in the journal L’Anthropologie.

With the authenticity of the cave verified, the archaeological spadework began anew. The relatively flat ceiling in the cave entrance is where the majority of artwork is to be found, though more can be found in the twisting passages and chambers deeper within the cave. It was discovered that the cave was occupied during two distinct phases: the first ended 18,000 years ago, and the second is between 16,600 to 14,000 years ago. In between, there is a 2,000 year gap when it was not occupied by humans at all. Sometime around 13,000 years ago a rock-fall sealed the cave entrance until modern times. It was only discovered again when a tree fell and the roots dislodged some rocks revealing a cavity beyond.

The artists used charcoal and ochre for their paintings and had used the natural contours of the cave walls to give a 3-dimensional effect to their painted figures and by far the most impressive and famous group are the herd of steppe bison, a long extinct species. There are other animals, too. Two horses, a large doe and a wild boar, all painted with the same vivid colours that the artist must have seen with his own eyes. French cave art takes first prize for its variety of animals and the quality of artwork, which in fact, is beyond the ability of most modern people, and to be honest, many modern self-acclaimed artists. But the question that has puzzled archaeologists is why they were painted at all.

Photograph of the steppe bisons

Although petroglyphs or engravings on the walls of human occupied caves had been found which have been dated at around 44,000 years old, full colour and form rock painting burst into human culture around 25,000 years ago. Archaeologists sometimes call this the “the day we learned to think”. Cave artwork began during what is called the last glacial maximum, (LGM) the coldest part of the last Ice Age. The artwork is not religious; there are no demons or deities in any of the pictures. Later paintings have drawings of stick men with bows and arrows and sometimes rows of scratches that could be a calendar, so what was the reason for the explosion in cave painting?

Humans at this time were all hunter-gatherers. Farming was around 14,000 years in the future, so to survive, these hunters needed to work together as a pack to hunt the food they needed. Family groups could not hope to feed themselves with just two or three hunters. The herd of bison shown at Altamira would most likely be animals that migrated seasonally through northern Spain, and like so many of the Ice Age animals, they were big. The steppe bison weighed in at around a ton and had horns that measured a meter across. The Aurouch, ancestor of modern cattle, also weighed about a ton and was about twice the size of a modern bull, standing seven feet tall at the shoulder. However, for the northern latitudes, the mammoth took first prize for size at ten feet tall and weighing around six tons. It needed organized teamwork to bring down one of these animals with just flint tipped spears, and one recent theory is that the paintings were a visual aid for more experienced hunters to show the young novices how to go about it. This may be true, but the quality of the paintings goes far beyond the simple line diagrams needed, and it may be that although simple drawings would have sufficed, the chance to show off with full colour pictures of the hunt was more than the artist could resist. What started off as a tutorial turned into an exhibition of the new suite of abilities that modern humans were to develop in time. Human cave painting of animals took place over a span of 20,000 years, and was the longest-lasting culture in human history. It endured for 800 generations and stretched from southern Spain to the Urals. But once the ice retreated and the forests returned, bringing smaller game like deer and boar, the caves were abandoned and cave art stopped.

_Credit_H. Collado.jpg_SIA_JPG_background_image.jpg)

Close up of hand stencils believed to have been painted by Neanderthals.

But humans were not the only hunter-gatherer inhabitants of Iberia during the Ice Age. Neanderthals predate the arrival of modern humans in the area and they also had a more primitive form of cave art that began 64,000 years ago. There are several sites in Spain where you can see their work. The Cave of Maltravieso in Cáceres, Extremadura, contains 71 hand stencils, some of which are from around this time.

But by far the best places to see how Neanderthals lived is at Ardales in Málaga province. The artwork that they left can hardly be called art compared to later humans and is limited to simple symbols rather than animal or human forms, but it is 40,000 years earlier than later cave paintings made by Homo Sapiens. Nevertheless, it represents the first stirrings of a new consciousness that was to transform the world.

Altamira is a long hike from Andalucía, but the centre has related displays with bi-lingual explanations and is well worth the visit if you tie it in with other places of interest and make a holiday of it. The real cave has been closed to visitors since 2002 because mould was found to be destroying the original paintings. A replica cave and museum were built nearby and completed in 2001 by Manuel Franquelo and Sven Nebel, reproducing the cave and its art.

Ardales is much easier to reach and has almost as good a display as Altamira with a section dedicated to the Neanderthals. Also, you can visit the beautiful village of Ardales and the ruins of its Moorish castle on a promontory above the pueblo. (The name Ardales is from the Arabic Ard Allah, meaning God’s country.) But, of course, the real attraction at Ardales are the embalses, which gives the area its other name, the Lake District of Málaga Province.

Just to finish off, little Maria who discovered the bison at Altamira married into the rich Botín family, and her children and grandchildren are among the current owners of Banco Santander. There is also a film starring Antonio Banderas called Finding Alatamira.

3

Like

Published at 10:21 PM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 10:21 PM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|