There are two cups in existence that claim to be the Holy Grail. One is in the Cathedral of Valencia and the other is in the Cathedral of Genoa. There is a third contender, The Chalice of Doña Urraca in León, but this is a doubtful latecomer, and owes its claim to authenticity to a book written in 2014.

So much has been written, and by so many, about the cup that Christ used at the Last Supper that the Holy Grail has become a metaphor for something so precious and unattainable as to be other worldly. There is no doubt Jesus used a cup at that famous meal, and it is mentioned by Mark and Luke and by the Apostle Paul in Corinthians, but the cup had no significance to the writers of the gospels; it was just a prop that Jesus used to explain his message to them. Matthew writes that Jesus said:

“Drink this, all of you; for this is My blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine until I drink it new with you in My Father’s kingdom.”

Over the centuries within the Catholic Church, the search for icons from Christ’s life became a holy quest all by itself. Just about every European cathedral has an icon; a piece of the cross, the hair of a saint or one of his bones. Having an icon became a way of getting one up on a rival bishop or neighbouring medieval city. Fake icons abound, and the fertile imagination of writers and romancers have fed the fevered minds of the faithful. The next time the cup appears in written records is sometime around the year 380, when St. John Chrysostom was commenting on Matthew’s account of the Last Supper. He says,

“The table was not of silver, the chalice was not of gold in which Christ gave His blood to His disciples to drink, and yet everything there was precious and truly fit to inspire awe.” Although 350 years after the event, his comments showed a growing awareness of the religious significance of the cup that Jesus used that night.

The first mention of the existence of an actual cup comes 190 years later in 570 from Antoninus of Piacenza, who wrote a travelogue of the holy places in Jerusalem which said that he saw “the cup of onyx, which our Lord blessed at the last supper.” He saw it in the Basilica built by Constantine close to Golgotha and the Tomb of Christ where it was displayed with other relics of Christ’s time.

But the legend of the fabulous Holy Grail with miraculous powers begins during the 1180’s, when Chrétien de Troyes wrote a romance for his patron, Philip I, Count of Flanders. (Romances were high-culture poetic narratives of chivalric heroism with the emphasis on love and courtly manners.) The poem was written in Old French and the grail appears in the unfinished fifth verse of Perceval ou le Conte du Graal. Philip provided Chrétien de Troyes with the original storyline, but died in 1191 while crusading at Acre in the Holy Land. The romance was about the adventures of a young knight, Perceval, who joins King Arthur’s court and gains distinction for bravery. During his travels he is invited to eat with the mysterious Fisher King, and one of the king’s serving girls carries a graal. In the morning, Perceval awakes alone and continues his journey. A young girl whom he meets that same morning admonishes Perceval for not asking the Fisher King about the graal and its significance.

Perceval arrives at the Grail Castle to be greeted by the Fisher King in an illustration for a 1330 manuscript. Source: Wikipedia.

The story now breaks off to follow Gawain, a favourite of King Arthur, in a new chapter which was also never finished. The reason that these works were left unfinished is assumed to be either the death of Philip or Chrétien de Troyes, but other writers soon jumped in to finish the epic poem. Before the turn of the 11th century, Robert de Boron wrote two poems, Joseph d'Arimathie in which the grail is used by Joseph of Arimathea to catch the blood of Christ at the crucifixion, and Merlin; the latter work survives only in fragments rendered in prose and written around 1210, possibly by Robert himself. Both were later translated into Middle English by Henry Lovelich in the mid-15th century. The two poems are thought to have been combined to form either a trilogy – with the Perceval verses forming the third part – or a tetralogy with the inclusion of the Lancelot-Grail stories leading to the Le Morte d'Arthur. (Death of Arthur) All of these romances were hugely popular in the middle ages. The writers had set the stage, and all that was required now was the star of the show; the Holy Grail itself.

The Grail of Valencia. Photo: Sylvain Billet.

The Holy Chalice of Valencia is an agate cup which has been enclosed in an ornate gold mount with handles so that the cup can be picked up without touching it. The cup itself was most likely made in a Palestinian or Egyptian workshop between the 4th century BC and the 1st century AD and its (alleged) history is the most-plausible of the two Grails. Seemingly, the cup was taken to Rome by St. Peter after the death of Christ, where it stayed in obscurity until Emperor Valerian began a witch-hunt against Christians in 258. Pope Sixtus II was forced to hide many of the sacred relics in far-flung places where the Romans could not find them. Pope Sixtus along with numerous bishops, priests, and deacons were put to death by Valerian.

Saint Lawrence in Huesca was the pope’s deacon in Spain, and the grail was delivered to him. That the pope removed the chalice from Rome is recorded in the Vatican records as “He took this glorious chalice”, and the phrasing of the translated passage indicates a high level of veneration for the grail. Alongside the Grail in the cathedral, written on vellum, is a list of items that the church had to divide up and hide amongst its members during the Roman persecution. Saint Lawrence is mentioned on this list, but another letter which accompanied this list and detailed the persecution by Valerian has been lost. A paper trail of documents concerning the grail leads us back as far as 1134, when it is mentioned in an inventory of the treasury of the monastery of San Juan de la Peña drawn up for the Canon of Zaragoza.

There is a more dubious alternative history for the Grail of Valencia, which is without the benefit any kind of proof. In this history the grail was acquired by a Roman soldier sometime during the third century and it was he who brought it back to his home in Huesca. When the Moors invaded in712 it was taken to San Juan de la Peña for safety. This is where the two histories join.

The grail was kept and venerated during many centuries among the relics of the Cathedral, but when Napoleon invaded in 1809 it was taken to Alicante, Ibiza and Palma de Mallorca. In 1916, it was finally housed in the old Chapter House, later called the Holy Chalice Chapel, but when Civil War broke out in Spain in 1936 it was again removed and hidden in Carlet.

The Vatican has never publicly said that the Grail of Valencia was the actual cup used by Christ. The nearest that the church will come to endorsing the grail is to say that it could possibly be the cup that Jesus used. Nevertheless, Pope John Paul II celebrated mass with the Holy Chalice in Valencia in November 1982, when he referred to the grail as “a witness to Christ's passage on earth”. In July 2006 Pope Benedict XVI also celebrated mass with the Holy Chalice calling it “this most famous chalice” paraphrasing words in the Roman Canon said to have been used by the first popes to refer to the Holy Grail before the 4th century in Rome.

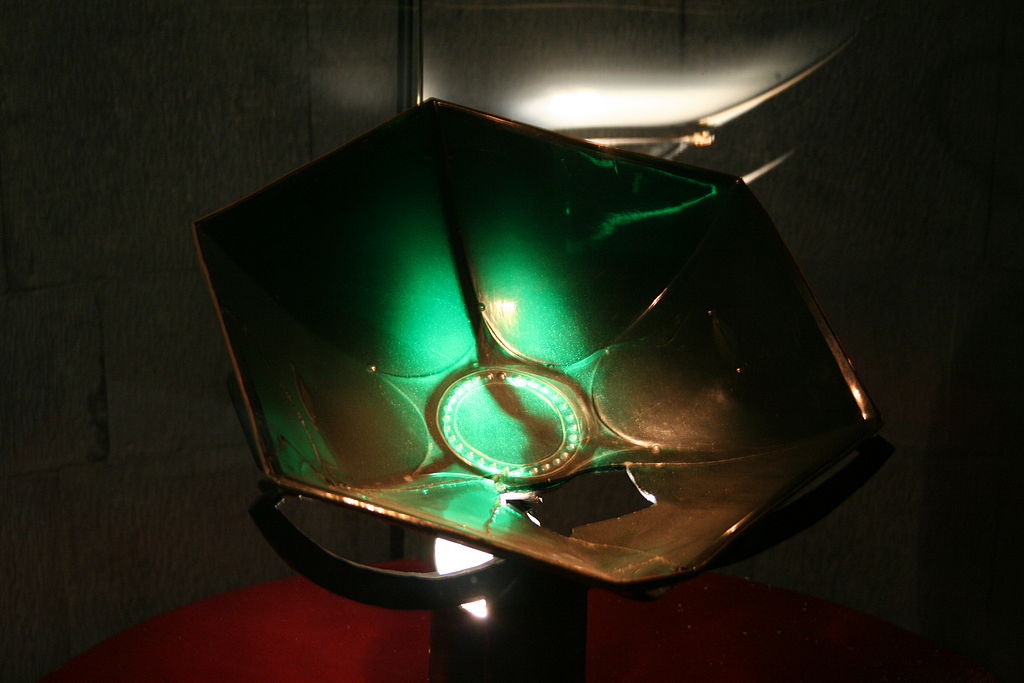

The Sacro Catino, or The grail of Genoa.

The other Grail, or Sacro Catino, in Genoa is very different in shape to the one in Valencia. It’s not a cup but a hexagonal dish made of green Egyptian glass. It was brought to Genoa by Guglielmo Embriaco as part of the spoils from the conquest of Caesarea in 1101. Embriaco was a Genoese merchant and military leader who came to the assistance of the Crusader States in the aftermath of the First Crusade. Even though Embriaco would later be considered as one of the founders of The Republic of Genoa, the Genuese did not have much respect for him. His nickname amongst his own countrymen was William the drunkard, and during the campaign, which was finally successful, he acquired a second sobriquet of William the mallethead. Guglielmo accepted the grail because he was told that it was, “made of a single emerald” a precious stone thought to have miraculous powers. It was not considered to be a holy relic until after the widespread success of the grail romances and the amplification of the legend by Jacobus de Voragine in 1290 in his literary work, Chronicon.

When Napoleon invaded in 1805 he seized the bowl and took it to Paris where it was damaged, and the world found out that it was not made from emerald but glass. It was returned to Genoa in 1816 where its popularity is still as great as ever.

The Chalice of Doña Urraca

The Chalice of Doña Urraca

The final Spanish grail is known as the Chalice of Doña Urraca and is kept in the Basilica of San Isidoro in León, Spain. It had never been considered as a Holy Chalice, and was only proposed as such in a 2014 book called Los Reyes del Grial. The book, which develops the hypothesis that this cup had been taken by Egyptian troops following the invasion of Jerusalem and the looting of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, then given by the Emir of Egypt to the Emir of Denia, who in the 11th century gave it to the Kings of León in order for them to spare his city in the Reconquista. Only the writer of the book claims that it is anything but an elaborately worked fake.

In the light of all the fabulous stories and romances written about the grail over the centuries, including all the modern books like Da Vinci Code and films like The Last Crusade, should we consider all the grails to be nothing more than elaborate fakes? The true story of the cup has been lost in all the fantasy and conspiracy generated by writers. I like to think that Indianna Jones has it right; when asked to choose the true true cup from all the bejewweled and golden chalices he spurns them and picks a simple cup as would be used by a carpenter.