When Queen Isabel agreed to fund Columbus’ first voyage, she spread the financial risk by asking a group of Seville-based traders to jointly invest in the voyage. Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco Medici was one of the very rich Florentine traders who employed trading agents in Seville, and Tomasso Capponi was one of these agents. Four years before Columbus was granted the money for his first voyage, di Pierfrancesco had become dissatisfied with the work of Capponi and he asked one of his Florence-based employees to go to Seville and assess candidates for his replacement. Based on his employee’s recommendations, Pierfrancesco sacked Capponi and replaced him with a Seville-based merchant named Gianotto Berardi. Beradi was perfect for the job; he already ran his own business in African slavery and ship chandlery, and was easily capable of managing the Medici's trade in Seville. The 41 year-old Medici employee who did the dirty on Cappioni was called Amerigo Vespucci.

Americo Vespucci: Painting: Christifano de'll Artisimo.

Vespucci moved to Seville sometime before 1492 and was working closely with Beradi in his business dealings, and when the queen asked for investors for Columbus’ first voyage, Berardi chipped in with half a million maravedis. When Columbus returned triumphant, the queen awarded Beradi the lucrative contract to provision Columbus's larger second fleet. In 1495, Berardi signed a contract with the crown to send 12 resupply ships to Hispaniola, and things were looking good for both Beradi and Vespucci. Unfortunately, Beradi died unexpectedly in December 1495 before he could complete the contract, leaving debts of 140,000 maravedis. But all was not gloom. Vespucci had met and married a Sevillian lady called Maria Cerezo, who was allegedly the daughter of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba the “Grand Captain” hero of the reconquest and capture of Granada. With this marriage, he improved his social standing in Seville by several pay-grades.

However, that’s not what put Vespucci on the map.

Realising that Columbus was out of his depth as governor of the Indies, and certainly under-qualified to be the governor of the huge continent that was growing in magnitude with each new exploration expedition, Isabel once more hedged her bets. She charged Rodríguez de Fonseca with creating an office of colonial administration from as early as 1493. From the very first meeting, Fonseca disliked Columbus, who he felt was assuming too much of the authority which should belong to the crown. With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to see that perhaps Fonseca would wish to take some of that authority from Columbus and have it for himself as an agent of the crown.

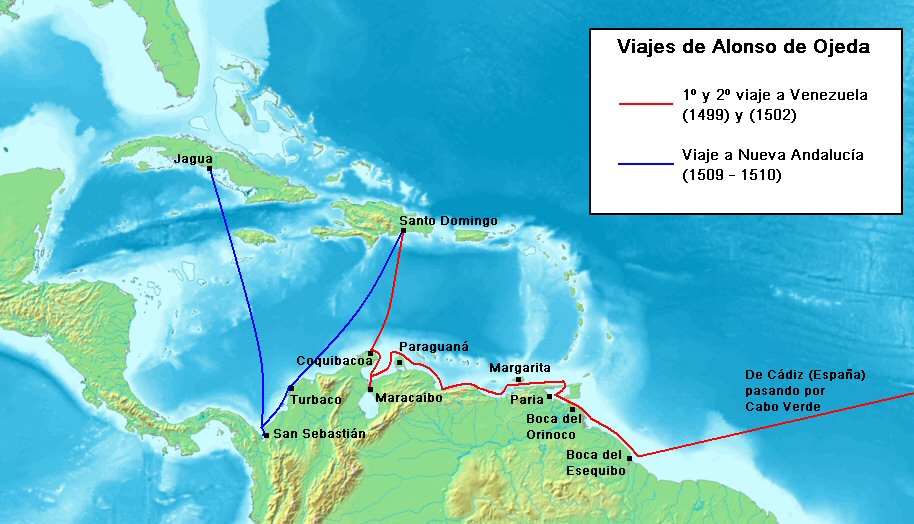

When Columbus got into difficulties in 1499, it was Fonseca who advised Isabel that he be removed as governor of the Indies. That same year, Fonseca began to organize a series of voyages commanded by such captains as Diego de Lepe and Rodrigo de Bastidas. All these captains had sailed with Columbus and knew the seas around the Indies. Alonso de Ojeda had returned to España from Hispaniola in 1496 disillusioned with the disjointed rule of Columbus and his mistreatment of the natives. It was no doubt his outspoken criticism of Columbus that caught Fonseca’s attention and influenced him to make Ojeda commander of the next voyage of exploration to be undertaken by the crown. Isabel and Ferdinand decided not to notify Columbus that they were sending rival explorers into what he had been promised would be his exclusive trading domain.

Ojeda had taken part in Columbus’ second voyage, and it was Ojeda who Columbus charged with finding Caonabo, the cacique who had destroyed Fort Navidad and killed all the men he had left behind on the first voyage. Ojeda presented Caonabo with a set of polished brass manacles and convinced him that they were a symbol of royalty in his own country. The moment the chief put on the manacles, Ojeda had him dragged away for punishment. In 1495, the first native rebellion took place at a river crossing where a fort had been built. The ten-man garrison were killed and the fort destroyed and Columbus ordered Ojeda to lead a 500 man force and secure the area. Fifteen hundred natives were captured and distributed to the settlers as slaves, with 600 of them shipped back to España to be sold in slave markets.

Alonso de Ojeda.

Ojeda’s flotilla of four ships set sail in 1499 with Juan de la Cosa as chief navigator and cartographer. Vespucci was on one of the ships, but his role is not recorded and the only reference to him is from much later when Ojeda remembered that "Morigo Vespuche" was one of his pilots. Their brief was to explore the coast line as far as they could with emphasis on locating the source of pearls that Columbus had reported finding. They made landfall in what is now French Guiana and the flotilla split up; Ojeda led two of the ships north, whilst the other two headed south carrying Vespucci. There are no official records of the southern voyage other than those later written by Vespucci himself, and according to him, they passed the mouth of the Amazon and were amazed to find that the ocean was still freshwater 25 miles out into the Atlantic. The two ships continued south for another 40 leagues (150miles) until they encountered a strong northerly current and could make no headway. They retraced their course northwards again and possibly made contact with the other two ships. The flotilla entered Lake Maracaibo on 24 August 1499, and the captains decided to end the exploration voyage here.

The whole voyage had been a financial failure. Except for a few pearls, a little gold and a few slaves, they had nothing to show to their backers. Santo Domingo was just a couple of days sailing due north from where they were, and so they left the mainland behind and headed for Hispaniola. They docked on 5 September, and as soon as the crews went ashore they ran into trouble. Those settlers faithful to Columbus realised that these men were trying to infringe on their hard-won trading privileges with the crown. Fighting broke out immediately and many of Ojeda’s men were killed.

With their tails between their legs, Ojeda’s crews returned to their ships and hastily left Hispaniola behind. They made a brief slave raid in the Bahamas, capturing 232 natives, and then returned to España. To add further to their chagrin, Pedro Alonso Niño, another one of Fonseca’s favourites, had docked just before them with a cargo of pearls from the Gulf of Paria and a contract with the crown of España to give 20% of their cargo to Castile, leaving them with a handsome profit. From then on, Pedro was known as Peralonso Niño.

Pedro Alonso Niño.

Pedro Alonso Niño.

However, Vespucci the salesman had his toe in the door, and was about to snatch victory from disaster. Upon his return to Puerto Santa Maria, Juan de la Cosa began updating the Mappa Mundi. He didn’t make the alterations himself, he had a team of cartographers who did that for him, and he was truthful in that he acknowledged each country’s separate claims. He added the discoveries of John Cabot, Vicente Pinzon, and Pedro Álvares Cabral by putting their national flags on the map.

Because of his seamanship and encyclopaedic knowledge of the Indies Juan de la Cosa was becoming an essential inclusion in every expedition to the Caribbean, and in October 1500 he sailed with Rodrigo de Bastidas and Vasco Núñez de Balboa on another voyage to the Indies. Amerigo Vespucci visited de la Cosa's office in 1500, probably to report data on coasts he had explored, and it is likely that when de la Cosa sailed with Rodrigo de Bastidas he left Vespucci in charge of the map updates.

Vespucci was still custodian of the updated Mappa Mundi when he received a letter from the Manuel I, King of Portugal, on an urgent matter that required his personal attendance at the royal court. He was cordially invited to bring along the Mappa Mundi, which Vespucci did. Once within the royal palace, he was offered the post of pilot on a Portuguese expedition to be led by Gonçalo Coelho to ascertain how much of the new continent was east of the Tordesillas line. Meanwhile, somewhere out of sight, the Mappa Mundi was being copied.

The expedition left Lisbon in May 1501, and they sailed to Cape Verde to take on provisions. It was here by pure chance that they met Cabral on his return voyage from India. Coelho’s fleet set out across the Atlantic and landed on August 17, 1501, near to a town now called Recife. They continued south following the coast, and on January 1, 1502, they anchored in a bay at the mouth of a small river which, because of the date, they called Rio de Janeiro. Their mission complete, they set out across the Atlantic again on February 13, 1502.

The log of the voyage was kept by Vespucci, and he was no navigator. His measured distances are hopelessly wrong and his astronomical observations woefully confusing and inaccurate. (To be fair, the instruments used were not that accurate, and they required competence in mathematics and astronomy that a trader would be unlikely to possess.) They arrived in back in Portugal sometime in the summer of 1502, and this is when the facts start to become muddled. What is known for sure is that Vespucci published his first booklet on his voyages to the Nova Mundi. The book was full of wonderful descriptions of the new lands and their people. It was extremely popular and was widely read throughout Europe. He followed it up in 1505 with another book along the same lines, which also sold well throughout Europe.

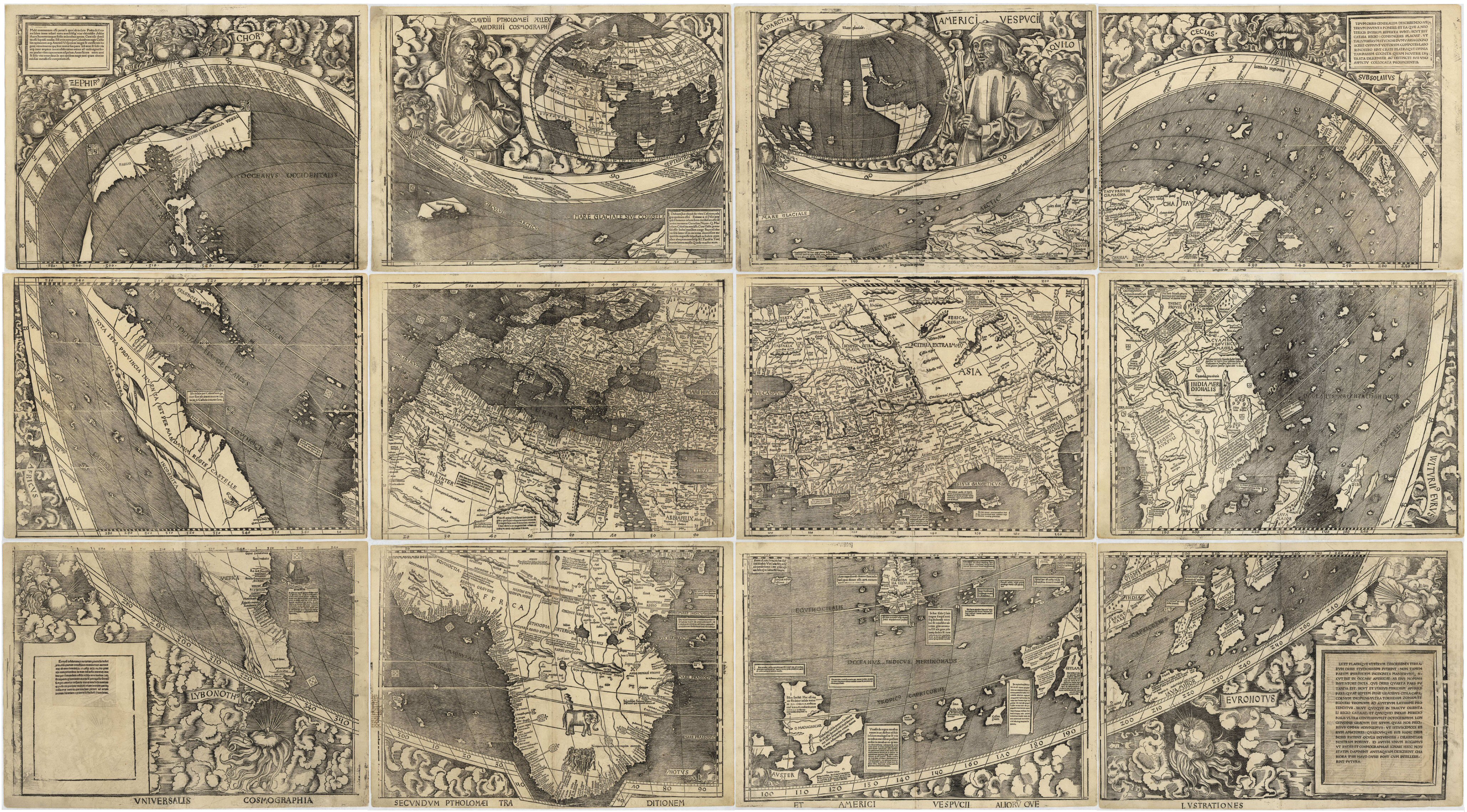

As Vespucci’s fame spread, inconsistencies began to appear in the record. Florentine official Piero Soderini received a letter supposedly from Vespucci in 1504 which he published the following year. It describes an expedition that left Spain on 10 May 1497, and returned on 15 October 1498 after exploring the mainland. These dates would show that Vespucci discovered the continent of America before Columbus. The letter is the only known reference to the voyage, and some of the historians, including a contemporary, Bartolomé de las Casas, believed it to be a fake. The navigational information in the letter is highly suspect. It states that the voyagers left Honduras and went northwest for 870 leagues; this would have put them on the other side of Mexico in the Pacific Ocean. The Soderini letter is one of two attributed to Vespucci that was edited and widely circulated during his lifetime. The publication of the letter prompted cartographer Martin Waldseemüller to recognize Vespucci's accomplishments in 1507 by applying the Latinized form "America" for the first time to a map showing the New World. Other cartographers followed suit, and by 1532 the name America was permanently affixed to the newly discovered continents.

The Waldseemüller map.

Vespucci returned to Seville sometime before 1505 and King Ferdinand welcomed him with open arms. In April 1505, he was declared a citizen of Castile and León. In 1508, (The year after Columbus died.) he was appointed to the newly created position of piloto mayor (master navigator) of España for the Casa de Contratación, which was overseen by Rodríguez de Fonseca, Columbus’ arch enemy. The salary for this post was 50,000 maravedis a year with an extra 25,000 for expenses. Vespucci was responsible for ensuring that ships’ pilots were adequately trained and licensed before sailing to the New World. He was also charged with compiling a "model map" based on input from pilots who were obligated to share what they learned after each voyage.

On the death of Queen Isabel in 1504, King Ferdinand allowed Fonseca almost unlimited scope in administering the overseas colonies. Rodríguez de Fonseca was successively named Bishop of Badajoz (1495), of Córdoba (1499), of Palencia (1504), and, finally, of Burgos (1514), one of Castile’s wealthiest dioceses. In 1519, he was also named Archbishop of Rossano in the Kingdom of Naples. In 1513, King Ferdinand asked the pope to create a new title for Fonseca; Patriarch of the West Indies, a position that would grant Fonseca a cardinal’s red hat. The pope declined; there was opposition within the church. A Dominican bishop, Bartolomé de las Casas, known as the Protector of the Indians, denounced Fonseca for his indifference to the cruelties that Spanish settlers inflicted on the native populations. When challenged over the slaughter of 7,000 children in Cuba, Fonseca was reported to have snapped, "And how does that concern me?" He was never made to answer for his indifference to the suffering in the Indies.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Columbus, the real hero of this story, has been marooned since 1503 at St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica.