Betrayal

Thursday, March 24, 2022

When Queen Isabel agreed to fund Columbus’ first voyage, she spread the financial risk by asking a group of Seville-based traders to jointly invest in the voyage. Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco Medici was one of the very rich Florentine traders who employed trading agents in Seville, and Tomasso Capponi was one of these agents. Four years before Columbus was granted the money for his first voyage, di Pierfrancesco had become dissatisfied with the work of Capponi and he asked one of his Florence-based employees to go to Seville and assess candidates for his replacement. Based on his employee’s recommendations, Pierfrancesco sacked Capponi and replaced him with a Seville-based merchant named Gianotto Berardi. Beradi was perfect for the job; he already ran his own business in African slavery and ship chandlery, and was easily capable of managing the Medici's trade in Seville. The 41 year-old Medici employee who did the dirty on Cappioni was called Amerigo Vespucci.

Americo Vespucci: Painting: Christifano de'll Artisimo.

Vespucci moved to Seville sometime before 1492 and was working closely with Beradi in his business dealings, and when the queen asked for investors for Columbus’ first voyage, Berardi chipped in with half a million maravedis. When Columbus returned triumphant, the queen awarded Beradi the lucrative contract to provision Columbus's larger second fleet. In 1495, Berardi signed a contract with the crown to send 12 resupply ships to Hispaniola, and things were looking good for both Beradi and Vespucci. Unfortunately, Beradi died unexpectedly in December 1495 before he could complete the contract, leaving debts of 140,000 maravedis. But all was not gloom. Vespucci had met and married a Sevillian lady called Maria Cerezo, who was allegedly the daughter of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba the “Grand Captain” hero of the reconquest and capture of Granada. With this marriage, he improved his social standing in Seville by several pay-grades.

However, that’s not what put Vespucci on the map.

Realising that Columbus was out of his depth as governor of the Indies, and certainly under-qualified to be the governor of the huge continent that was growing in magnitude with each new exploration expedition, Isabel once more hedged her bets. She charged Rodríguez de Fonseca with creating an office of colonial administration from as early as 1493. From the very first meeting, Fonseca disliked Columbus, who he felt was assuming too much of the authority which should belong to the crown. With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to see that perhaps Fonseca would wish to take some of that authority from Columbus and have it for himself as an agent of the crown.

When Columbus got into difficulties in 1499, it was Fonseca who advised Isabel that he be removed as governor of the Indies. That same year, Fonseca began to organize a series of voyages commanded by such captains as Diego de Lepe and Rodrigo de Bastidas. All these captains had sailed with Columbus and knew the seas around the Indies. Alonso de Ojeda had returned to España from Hispaniola in 1496 disillusioned with the disjointed rule of Columbus and his mistreatment of the natives. It was no doubt his outspoken criticism of Columbus that caught Fonseca’s attention and influenced him to make Ojeda commander of the next voyage of exploration to be undertaken by the crown. Isabel and Ferdinand decided not to notify Columbus that they were sending rival explorers into what he had been promised would be his exclusive trading domain.

Ojeda had taken part in Columbus’ second voyage, and it was Ojeda who Columbus charged with finding Caonabo, the cacique who had destroyed Fort Navidad and killed all the men he had left behind on the first voyage. Ojeda presented Caonabo with a set of polished brass manacles and convinced him that they were a symbol of royalty in his own country. The moment the chief put on the manacles, Ojeda had him dragged away for punishment. In 1495, the first native rebellion took place at a river crossing where a fort had been built. The ten-man garrison were killed and the fort destroyed and Columbus ordered Ojeda to lead a 500 man force and secure the area. Fifteen hundred natives were captured and distributed to the settlers as slaves, with 600 of them shipped back to España to be sold in slave markets.

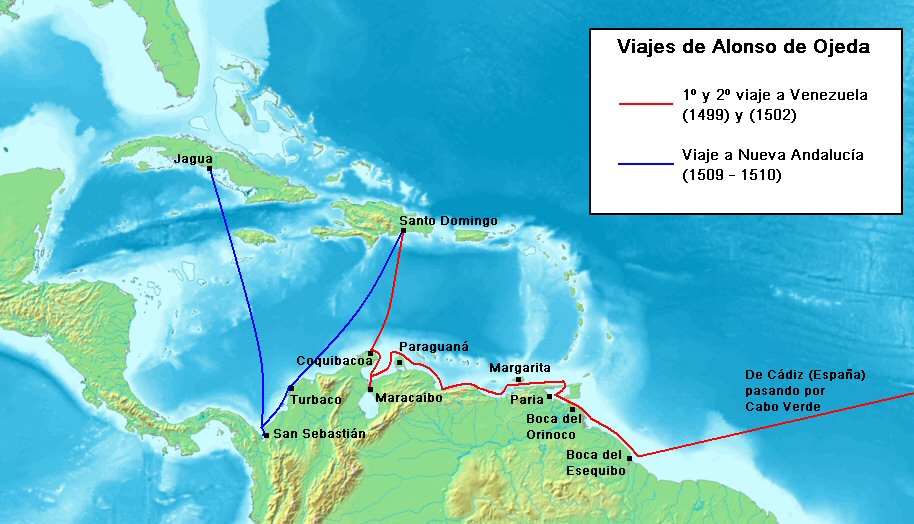

Alonso de Ojeda.

Ojeda’s flotilla of four ships set sail in 1499 with Juan de la Cosa as chief navigator and cartographer. Vespucci was on one of the ships, but his role is not recorded and the only reference to him is from much later when Ojeda remembered that "Morigo Vespuche" was one of his pilots. Their brief was to explore the coast line as far as they could with emphasis on locating the source of pearls that Columbus had reported finding. They made landfall in what is now French Guiana and the flotilla split up; Ojeda led two of the ships north, whilst the other two headed south carrying Vespucci. There are no official records of the southern voyage other than those later written by Vespucci himself, and according to him, they passed the mouth of the Amazon and were amazed to find that the ocean was still freshwater 25 miles out into the Atlantic. The two ships continued south for another 40 leagues (150miles) until they encountered a strong northerly current and could make no headway. They retraced their course northwards again and possibly made contact with the other two ships. The flotilla entered Lake Maracaibo on 24 August 1499, and the captains decided to end the exploration voyage here.

The whole voyage had been a financial failure. Except for a few pearls, a little gold and a few slaves, they had nothing to show to their backers. Santo Domingo was just a couple of days sailing due north from where they were, and so they left the mainland behind and headed for Hispaniola. They docked on 5 September, and as soon as the crews went ashore they ran into trouble. Those settlers faithful to Columbus realised that these men were trying to infringe on their hard-won trading privileges with the crown. Fighting broke out immediately and many of Ojeda’s men were killed.

With their tails between their legs, Ojeda’s crews returned to their ships and hastily left Hispaniola behind. They made a brief slave raid in the Bahamas, capturing 232 natives, and then returned to España. To add further to their chagrin, Pedro Alonso Niño, another one of Fonseca’s favourites, had docked just before them with a cargo of pearls from the Gulf of Paria and a contract with the crown of España to give 20% of their cargo to Castile, leaving them with a handsome profit. From then on, Pedro was known as Peralonso Niño.

Pedro Alonso Niño. Pedro Alonso Niño.

However, Vespucci the salesman had his toe in the door, and was about to snatch victory from disaster. Upon his return to Puerto Santa Maria, Juan de la Cosa began updating the Mappa Mundi. He didn’t make the alterations himself, he had a team of cartographers who did that for him, and he was truthful in that he acknowledged each country’s separate claims. He added the discoveries of John Cabot, Vicente Pinzon, and Pedro Álvares Cabral by putting their national flags on the map.

Because of his seamanship and encyclopaedic knowledge of the Indies Juan de la Cosa was becoming an essential inclusion in every expedition to the Caribbean, and in October 1500 he sailed with Rodrigo de Bastidas and Vasco Núñez de Balboa on another voyage to the Indies. Amerigo Vespucci visited de la Cosa's office in 1500, probably to report data on coasts he had explored, and it is likely that when de la Cosa sailed with Rodrigo de Bastidas he left Vespucci in charge of the map updates.

Vespucci was still custodian of the updated Mappa Mundi when he received a letter from the Manuel I, King of Portugal, on an urgent matter that required his personal attendance at the royal court. He was cordially invited to bring along the Mappa Mundi, which Vespucci did. Once within the royal palace, he was offered the post of pilot on a Portuguese expedition to be led by Gonçalo Coelho to ascertain how much of the new continent was east of the Tordesillas line. Meanwhile, somewhere out of sight, the Mappa Mundi was being copied.

The expedition left Lisbon in May 1501, and they sailed to Cape Verde to take on provisions. It was here by pure chance that they met Cabral on his return voyage from India. Coelho’s fleet set out across the Atlantic and landed on August 17, 1501, near to a town now called Recife. They continued south following the coast, and on January 1, 1502, they anchored in a bay at the mouth of a small river which, because of the date, they called Rio de Janeiro. Their mission complete, they set out across the Atlantic again on February 13, 1502.

The log of the voyage was kept by Vespucci, and he was no navigator. His measured distances are hopelessly wrong and his astronomical observations woefully confusing and inaccurate. (To be fair, the instruments used were not that accurate, and they required competence in mathematics and astronomy that a trader would be unlikely to possess.) They arrived in back in Portugal sometime in the summer of 1502, and this is when the facts start to become muddled. What is known for sure is that Vespucci published his first booklet on his voyages to the Nova Mundi. The book was full of wonderful descriptions of the new lands and their people. It was extremely popular and was widely read throughout Europe. He followed it up in 1505 with another book along the same lines, which also sold well throughout Europe.

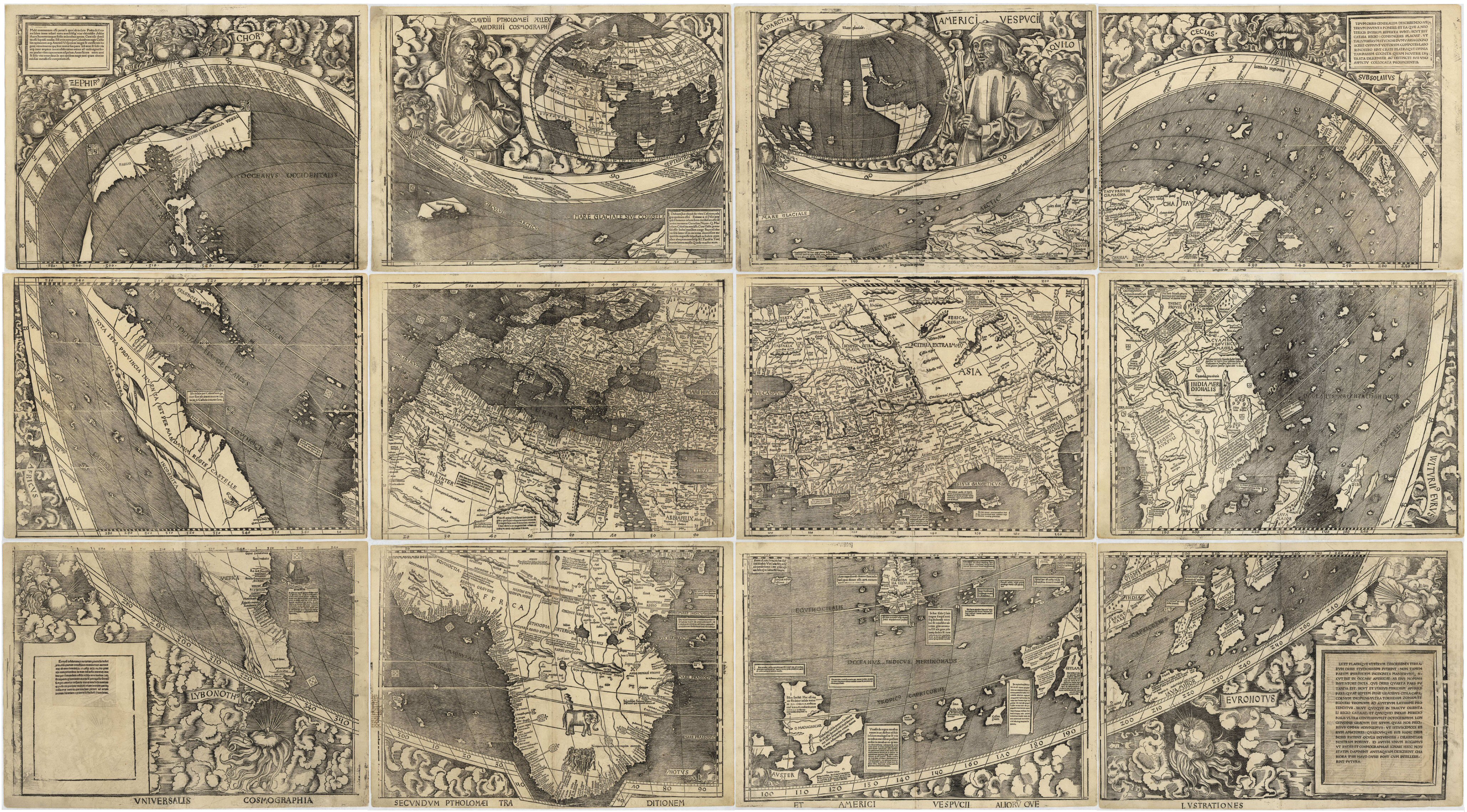

As Vespucci’s fame spread, inconsistencies began to appear in the record. Florentine official Piero Soderini received a letter supposedly from Vespucci in 1504 which he published the following year. It describes an expedition that left Spain on 10 May 1497, and returned on 15 October 1498 after exploring the mainland. These dates would show that Vespucci discovered the continent of America before Columbus. The letter is the only known reference to the voyage, and some of the historians, including a contemporary, Bartolomé de las Casas, believed it to be a fake. The navigational information in the letter is highly suspect. It states that the voyagers left Honduras and went northwest for 870 leagues; this would have put them on the other side of Mexico in the Pacific Ocean. The Soderini letter is one of two attributed to Vespucci that was edited and widely circulated during his lifetime. The publication of the letter prompted cartographer Martin Waldseemüller to recognize Vespucci's accomplishments in 1507 by applying the Latinized form "America" for the first time to a map showing the New World. Other cartographers followed suit, and by 1532 the name America was permanently affixed to the newly discovered continents.

The Waldseemüller map.

Vespucci returned to Seville sometime before 1505 and King Ferdinand welcomed him with open arms. In April 1505, he was declared a citizen of Castile and León. In 1508, (The year after Columbus died.) he was appointed to the newly created position of piloto mayor (master navigator) of España for the Casa de Contratación, which was overseen by Rodríguez de Fonseca, Columbus’ arch enemy. The salary for this post was 50,000 maravedis a year with an extra 25,000 for expenses. Vespucci was responsible for ensuring that ships’ pilots were adequately trained and licensed before sailing to the New World. He was also charged with compiling a "model map" based on input from pilots who were obligated to share what they learned after each voyage.

On the death of Queen Isabel in 1504, King Ferdinand allowed Fonseca almost unlimited scope in administering the overseas colonies. Rodríguez de Fonseca was successively named Bishop of Badajoz (1495), of Córdoba (1499), of Palencia (1504), and, finally, of Burgos (1514), one of Castile’s wealthiest dioceses. In 1519, he was also named Archbishop of Rossano in the Kingdom of Naples. In 1513, King Ferdinand asked the pope to create a new title for Fonseca; Patriarch of the West Indies, a position that would grant Fonseca a cardinal’s red hat. The pope declined; there was opposition within the church. A Dominican bishop, Bartolomé de las Casas, known as the Protector of the Indians, denounced Fonseca for his indifference to the cruelties that Spanish settlers inflicted on the native populations. When challenged over the slaughter of 7,000 children in Cuba, Fonseca was reported to have snapped, "And how does that concern me?" He was never made to answer for his indifference to the suffering in the Indies.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Columbus, the real hero of this story, has been marooned since 1503 at St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica.

0

Like

Published at 9:04 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 9:04 PM Comments (0)

One last chance

Friday, March 11, 2022

Columbus and his brothers were thrown into prison upon their arrival in Cádiz. There they remained for six weeks before a busy King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel deigned to give them audience on 12 December 1500 in the Alhambra palace in Granada. Whilst he had been incarcerated in Cádiz he had written a bitter letter to a friend.

“I have placed under their sovereignty more land than there is in Africa and Europe, and more than 1,700 islands... In seven years I, by the divine will, made that conquest. At a time when I was entitled to expect rewards and retirement, I was incontinently arrested and sent home loaded with chains…”

He wore a short sleeved shirt when he stood before the royals, so that they could see the raw scars left by the chains and made an impassioned plea for their mercy. Real tears ran down his face as he admitted his faults and mistakes.

“I beg your graces, with the zeal of faithful Christians in whom their Highnesses have confidence, to read all my papers, and to consider how I, who came from so far to serve these princes... now at the end of my days have been despoiled of my honour and my property without cause, wherein is neither justice nor mercy.”

The king and queen took pity on the brothers, and they were released. Isabel was furious that Bobadilla had also exceeded his authority, and ordered his return. He would be replaced by another avaricious nobleman, Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres. The power-plays and the stakes were too high now for Columbus to be a player. However, he kept his title of Admiral and Viceroy and Bobadilla was ordered to return Columbus’ possessions.

The royal couple knew full-well about the attempts to sabotage Columbus’ meteoric rise on the world stage. When Martín Alonso Pinzón, captain of the renegade ship, the Pinta, who had deserted Columbus on the first voyage, landed at Galicia in Spain, he had actually arrived before Columbus, who had been delayed by the King of Portugal in the Azores and later in Lisbon. Hoping to claim all the credit and relate his version of the voyage before Columbus could malign him, Pinzón dispatched a letter to the royals requesting a private audience with them. It was rejected, and he was ordered not to come to Barcelona except in the company of Columbus. A shamed Pinzon docked in Palos just hours after Columbus arrived. He died there shortly after, suffering from illness caused by the hardships of the voyage. Columbus never reported the mutiny of Juan de la Cosa when the Santa Maria had run aground under very strange circumstances. This would normally a hanging offence, and de la Cosa was to be involved in even more scandal and subterfuge.

When Columbus was provisioning his fleet in Seville for the second voyage in June 1493 he had to commandeer his ships from whatever was available in local ports at the time, and he soon had leased 17 ships “large and small” from their owners. As before, their crews became paid sailors in the queen’s navy regardless of their status before.

This does not mean to say that they were press ganged into the enterprise. There were plenty of volunteers, some of whom were willing to serve without pay. Columbus chose 1500 men for various duties. Some were to be armed as soldiers and others would become settlers in the new lands. The queen issued them with new arms and armour, which they promptly sold in Seville and replaced with old and rusty weapons. Similarly, the fine cavalry horses supplied by Isabel were exchanged for old nags at a large profit. After hearing stories of docile unarmed natives the crew had decided there would be no battles like the ones they fought during the reconquest. The wholesale fiddling of the queen’s funding continued with the provisions loaded onto the ships. Short measure in filling the barrels, leaky barrels, salted beef that was near to going off. Food to be cooked on the journey that was ticked off on the manifest but was entirely missing. One of the officials that Columbus was to take with him alerted Queen Isabel who sent officers to arrest the culprits and ensure that the ships were properly provisioned. They waded into the contractors who were now only too happy to produce the correct supplies.

But as Governor, Columbus had overstepped a line in trustworthiness in his dealings with the natives and settlers. Isabel had wanted the natives to be converted to Christianity. She was bitter when greed and slavery had replaced that wish. Columbus now had to use all his powers of persuasion to redeem his reputation. His only justification for another expedition was his belief that there was an undiscovered passage to China beyond the islands that he had already discovered. Undoubtedly, it was his eagerness to face the perils of exploration once again and his atonement for his previous mistakes that convinced them to fund him again. What may have prompted them to trust him were the alarming gains made by Portugal with the voyages of Vasco da Gama and Cabral. Valuable time had been lost in squabbling over a small group of islands when, as was becoming obvious, a huge continent was there to be claimed.

On 11 May 1502, Columbus sailed on his fourth and last voyage with four ships carrying 147 men and strict orders from the king and queen not to stop at Hispaniola, but only to search for a westward passage to the Indian Ocean. He was accompanied on his flagship, the Capitana, by his 13-year old son, Ferdinand, and his stepbrother, Bartolomeo. The other ships were named the Gallega, Vizcaína, and Santiago de Palos. For some unexplained reason, they sailed first to Arzila on the Moroccan coast to rescue Portuguese soldiers who Columbus heard were besieged by the Moors. When they arrived the siege had been lifted and so they sailed on to the Canary Islands. They made good time crossing the Atlantic, and made landfall at Carbet on the island of Martinique on June 15. It took them another two weeks to island-hop north to the one island that he had been forbidden to land on. He arrived at the port of Santo Domingo, Hispaniola, on June 29 and was immediately refused entry despite having urgent need of repairs to one of his ships and the threat of an approaching storm. Unable to take shelter in the port, his tiny fleet moved a few kilometres along the coast to the west and anchored in the mouth of the Haina River.

Governor Bobadilla had received the letter from Queen Isabel ordering to return Columbus’ seized assets and return to España, but when he was given the news of Columbus’ arrival he panicked, and he and many of his crooked entourage loaded their belongings onto ships and prepared to sail. Despite the approaching hurricane and a warning from Columbus, a convoy of 30 ships left Santo Domingo and sailed into the teeth of the storm. All the gold that Bobadilla had confiscated when he arrested Columbus (an estimated US$10 million) was loaded onto the least seaworthy ship of the fleet, the Aguya. They didn’t get far before the storm scattered them like windblown leaves. Some were driven back to Santo Domingo, where even the harbour was no protection, and they sank in full view of the quay. Bobadilla’s ship is believed to have reached the eastern end of Hispaniola where it sank with all hands. Something like 20 ships were lost when they entered the Atlantic and met the full force of the hurricane. Around 500 people drowned, and if you believe in avenging angels, then the fact that they were all Columbus’ enemies and accusers will give you some satisfaction; I am sure that it did Columbus. However, one of the ships that did manage to dock safely in Santo Domingo disgorged Juan de la Cosa. He had narrowly survived the storm, but whilst Columbus was in the area, he lay low. Columbus’ guardian angels were still watching over him, because by what can only be described as a miracle, the only ship that made it back to España was the Aguya, carrying all Columbus’ gold. Even then, many of his enemies at court accused him of summoning supernatural powers to bring the storm that punished his accusers. (Hurricane is a Taíno word.)

Map of 4th voyage Credit to Keith Pickering.

When the hurricane had passed, Columbus regrouped his little fleet and sailed northwest stopping briefly at Jamaica and Cuba to top up his provisions and drinking water. The ships then turned west and on July 30, 1502, they landed Guanja, one of the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras. It was on August 14 that they finally landed on the mainland at Puerto Castilla, near Trujillo, Honduras. For the next two months he searched the coast for the passage that would let him into what he thought would be the China Sea. They arrived in Almirante Bay, Panama, on 16 October having found no such passage, and Columbus was finally beginning to realise that this was an entirely new unknown continent. (He was, in fact, just 60km away from the Pacific Ocean.) On his voyage down the coasts of modern-day Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama, Columbus had seen no signs of other Europeans, but had been introduced to cacao (the cocoa bean) and had seen a large canoe which he described “was as long as a galley”.

Once again he was promised “gold without limit” by the Ngobe natives, and in mid-November, he prepared to sail on another wild-goose chase to a province called Ciguare, which they told him “lie just nine days’ journey by land to the west”, or some 200 miles from his location in Veragua. He had set off on this journey, when on December 5 he encountered a storm more severe than any that he had ever encountered. He writes:

“For nine days I was as one lost, without hope of life. Eyes never beheld the sea so angry, so high, so covered with foam. The wind not only prevented our progress, but offered no opportunity to run behind any headland for shelter; hence we were forced to keep out in this bloody ocean, seething like a pot on a hot fire. Never did the sky look more terrible; for one whole day and night it blazed like a furnace, and the lightning broke with such violence that each time I wondered if it had carried off my spars and sails; the flashes came with such fury and frightfulness that we all thought that the ship would be blasted. All this time the water never ceased to fall from the sky; I do not say it rained, for it was like another deluge. The men were so worn out that they longed for death to end their dreadful suffering.”

He abandoned the search for gold after the storm, and after a few weeks of exploration he established a garrison in in January 1503 at the mouth of the Belén River, close to Panama. Things went from bad to worse when the local tribe leader, El Quibían, refused to allow them to explore up the river Belén. The chief was captured, but escaped and returned with an army and attacked the ships causing o much damage that one had to be abandoned. The remainder of the fleet of set course for Hispaniola on April 16, but ran into another storm which damaged all of the ships, and his exhausted and rebellious captains and crews were forced to beach them in in St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica, on 25 June.

Diego Méndez de Segura, who had been assigned as personal secretary to Columbus, and a Spanish shipmate called Bartolomé Flisco, along with six natives, took a native canoe and paddled to Hispaniola (A distance of nearly a thousand kilometres.) to bring help. The new governor, Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres, was jealous of Columbus’ renewed status and prevaricated with rescue efforts. Columbus and the 230 men of his crews would remain marooned on Jamaica for six months. (Other sources give a year.) Meanwhile, events on the Iberian Peninsula were gathering pace.

4

Like

Published at 10:26 AM Comments (4)

4

Like

Published at 10:26 AM Comments (4)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|