Enrique, king of … well, nothing, flew into a rage when he heard about the marriage of Isabel and Ferdinand. His seedy and devious advisors, chief of whom was Juan Pacheco, the Marquis of Villena, put Joanna forward as the rightful heir to the crown. In a breathtaking betrayal, the Archbishop of Toledo left Isabel’s court to unite with his great-nephew, Juan Pacheco, to support him with his claim. This foul crew were even more enraged when Isabel gave birth to a girl, whom she named Isabella after her mother, just over eleven months after the marriage. (2 Oct 1470) To the delight of the nobles of Castile, this was a much better alternative to the embarrassing Beltraneja who Enrique was proposing as heir. Tensions rose within the kingdom, and to defuse this situation, Isabel and Ferdinand met with Enrique to discuss matters in order to give him some measure of respect and reassurance of his royal lineage.

(So far, this account has seen at least two mysterious deaths and one suspected poisoning, but the twist that wins the prize happens now.)

Shortly after the meeting with Isabel and Ferdinand, on the 1st October 1474, the thorn in everybody’s side, Juan Pacheco, died suddenly in Trujillo. His son, Diego, ingratiated himself with King Enrique and stepped into his dead father’s shoes, but six weeks after Pacheco died, King Enrique died on 11 December 1474, and on the 13th December 1474, Isabel was crowned undisputed Queen of Castile.

You would think that this would be the end of Isabel’s worries, but no.

Diego Pacheco, backed by the Archbishop of Toledo, invited King Afonso V of Portugal (43 year-old uncle of Joanna) to marry the 13 year-old and invade Castile to take the throne from Isabel. Alfonso’s first wife had died in 1455, and to the king, this seemed like a reasonable offer at the time.

In May 1475, the Portuguese army crossed into Spain and advanced to Plasencia. Here Afonso married Joanna and began his campaign to take the Castilian crown. The war raged back and forth for almost a year until 1 March 1476, when the Battle of Toro took place, a battle in which both sides claimed victory, but neither won.

The armies fought each other to a standstill, and King Afonso was forced to retreat and regroup his forces. Ferdinand showed his genius by sending messengers out to all the cities of Castile and the nearby kingdoms that he had crushed the Portuguese in a great military victory. Overnight, support for Joanna collapsed.

To capitalise on the victory, Isabel convoked courts in Segovia in 1476, where her eldest child, Isabella was proclaimed as heiress to the crown of Castile, thus legitimising and strengthening her own claim to the throne. Later the same year, inspired by her husband’s successes in battle, Isabel led an army against an uprising in Segovia while Ferdinand was fighting elsewhere. She successfully negotiated a peace deal with the rebels, much to the surprise of her military advisors. The nobles of the kingdoms were watching events, and they realised that Isabel was becoming a force to be reckoned with.

He had to defuse this dispute to ensure Christian stability in a Europe that was beset in the east a new order. Several diverse principalities of Anatolia had unified by 1453 to become the Ottoman Empire, and led by Mehmed the Conqueror, had ended the old Roman Byzantine Empire by taking Constantinople in 1454, and then advancing into Europe by taking the Balkans. They had closed all trade routes by sea and land to the orient. This represented a huge financial loss to all Christendom and a threat to the Catholic Church.

This is where the wheeling and dealing started.

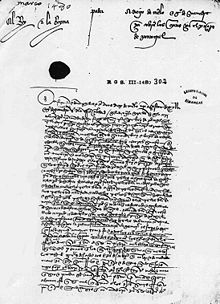

Pope Sixtus IV now stepped in to end the dispute over Castilian succession. To avoid further bloodshed and more costly wars, Isabel and Ferdinand were urged to sign a treaty with King Afonso and his son, Prince John of Portugal. The involvement of one of his bishops in the double-dealing between kingdoms, to say nothing of the forging of papal signatures, must have angered him more than a little.

The treaty of Alcáçovas

The treaty of Alcáçovas

The treaty that the pope offered had five parts:

The first part was an agreement by both sides to abandon all claims on each other’s thrones.

The second part was to grant Portugal exclusive rights to all Atlantic trade.

The third part was about the fate of Joanna, who had been an innocent pawn in all of this. The pope annulled her marriage with King Afonso on the grounds that she was too closely related to him, (consanguinity) and rendered her ineligible for either crown.

The forth part was a contract to marry Isabel’s daughter, Isabella, to Afonso, the son of Prince John of Portugal.

The final part was to pardon all the Castilian supporters of Joanna.

The Treaty of Alcáçovas, as it became known, was signed by both sides on September 4, 1479.

It was not a very fair treaty as far as Castile was concerned, but Isabel and Ferdinand were backed into a corner. Granting Portugal the exclusive right of navigation and commerce in all of the Atlantic Ocean south of the Canary Islands meant that España was practically blocked out of the Atlantic and deprived of any share in the gold of Guinea. This created unrest among Andalusia’s nobles, who feared that they had bought peace at too high a price and had restricted their expansion into the Atlantic.

It was not all loss to the Catholic family, on 30 June 1478 Isabel further secured her place as ruler with the birth of her son, John, Prince of Asturias, and in 1479, Ferdinand’s father died and he became King of Aragon joining the kingdoms of Aragon, Castile and León into a united country.

Meanwhile, law and order had broken down in the kingdoms, and robber bands made normal trade and commerce difficult. Isabel and Ferdinand created a militia whose sole purpose was to police their kingdoms and eliminate the bandits. She gradually gained more control of the economy, and stability returned, but España was desperately poor.

With Atlantic maritime trade thwarted by Portugal, and Mediterranean trade with the east blocked by the Ottoman Empire, Isabel turned her eyes to the south, where a large part of Iberia was still ruled by the Moors whose caliph Muhammad XII oversaw rich farmlands from his capitol in Granada. They had gold and jewels in abundance, and were probably still trading with the east.

In 750, the Galicians had been the first to force the occupying Muslims from their lands in the northernmost tip of Iberia, and the Reconquista had been raging ever since. The first crusade was started on November 27, 1095 by Pope Urban II when he gave a sermon outside the Cathedral at Clermont, Auvergne, urging the nobles to unite and liberate Jerusalem. The Holy wars were in reality organised raids to collect as much booty as the Christian invaders could take from the Moors. A noble religious cause was just a good excuse for daylight armed robbery. This had been going on for 729 years when Isabel began planning the final campaign to drive the Moors from Iberia.

It took twelve years, with Christian troops advancing a little more each year. During this campaign Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba rose to prominence and became Isabel’s most trusted general. A masterful strategist and tactician, Córdoba constantly refined the army of España, gaining himself the unofficial title of El Gran Capitan. His training brought the troops under his command to a new level of efficacy not seen since Roman times. He trained his men in the use of pikes as a defence against the dreaded jinetes, the much feared Moorish cavalry, and he was one of the first Europeans to introduce specialised regiments trained in the use firearms onto the battlefield. His visionary training made the Spanish army the dominant force in Europe for more than a century and a half. Isabel rewarded him by making him Duke of Santiángelo in 1497.

But it was in the final capitulation of the Moors at the Alhambra palace in Granada in 1492 that brought Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba to the forefront. It was he who negotiated the final surrender terms with Caliph Muhammad. Gonzalo spoke Arabic fluently and was highly respected by both sides as an honourable man who would deal fairly with the Moors. King Ferdinand had little respect for the outgoing Moors and as soon as he entered the palace he removed everything of value. But the greatest treasure of Moorish civilisation was in their philosophy, medicine and science, and this was to be found in the libraries which were abandoned when they left. Ferdinand made a show of emptying the libraries and publicly burning all the books.

Worse was to follow. Intolerance of anything Islamic had begun to grow into intolerance of anything not Catholic. Tens of thousands of Moors had been forced to convert to Catholicism during the reconquest though many had retained their Islamic faith and worked in society as doctors, lawyers and artisans. So had the Jews, but posters began to appear depicting Jews as necromancers with dark and evil rituals and a cancer was growing that the conversos were untrustworthy and secretly worshiping their own prophets. As early as 1478, while Ferdinand and Isabella were still consolidating their kingdom, they made formal application to the Pope for a tribunal of the Inquisition in Castile to investigate these and other suspicions. Moors and Jews had never had full equal rights within Christian lands and were taxed more than their Christian counterparts. This culminated in the Alhambra decree of 1492 issued by Isabel and Ferdinand requiring that all Jews convert to Catholicism or leave España. This edict would later be watered down in its severity, but for the Jews in España it was catastrophic, and the enforcement of the edict by over-zealous officials and the inflamed racist mobs who persecuted the Jews was close to genocide. All their possessions were seized and they were only allowed to take the clothes they stood in as they fled en mass. However, the booty collected was added to the almost empty coffers of the kingdom drained by ten years of constant warfare and the battles with her half-brother over the crown.

The gamble that she took to finance Columbus’ insane theory was small fry to the gambles that she was taking with the newly formed and victorious nation of España, but even though it brought huge dividends, it also brought the jealousy of King Manuel I of Portugal.

King Manuel I of Portugal.

King Manuel I of Portugal.

Isabel was acutely aware that she needed to cement trading ties with other countries, and her growing family was to be instrumental in securing an income for España. The Treaty of Alcáçovas obliged Isabel to marry her daughter, Isabella, to King Manuel of Portugal and Isabella became Queen of Portugal at the age of 27 in September 1497, but she only reigned as queen for a year before she died. Portugal had always been Castile’s rich neighbour and a family bond with King Manuel was crucial, so Isabel betrothed her third daughter, 15 years-old Maria, to be married to King Manuel to replace Isabella. It seems callous now, but to keep her country solvent, she needed peace, and time to make other connections.

Los Reys Catholicos, Museo del Prado.

Isabel’s pride and joy was her son Juan, who was to be her heir to the throne. He was married to the Archduchess Margaret of Austria, but tragedy struck when he became ill and died at the age of 19 in 1497 leaving no heir. Isabel took his death badly and never really recovered her spirit; her health began to deteriorate. That left Juanna, who became the female heir at the age of 18 and who was dutifully married to Philip the Handsome. From her infancy Juanna had been a problem child. She was given to tantrums and irrational behaviour that caused her mother, not the most tolerant of women, to use sometimes draconian methods to control her. However, once married, Isabel hoped that she would be somebody else’s problem. She was wrong.

Isabel and Ferdinand had achieved so much, but they are overshadowed in history by seemingly insignificant events whilst she was reforming España. Reluctantly agreeing to fund Columbus was one, but Queen Isabel would only see a small part of the revolution that her life brought to the world. Her least likely daughter, Catherine, would bring changes that would rock Christendom and cause a schism in the Christian faith that is still a problem now. It was not what she did that brought the changes, but rather something that she couldn’t do.