The furious artist

Saturday, January 30, 2021

For artistic rivalry that was bitter, and the next Last Supper, we have to go to Venice in 1518, the year before Leonardo died, and two years before the copies of his Last Supper were begun.

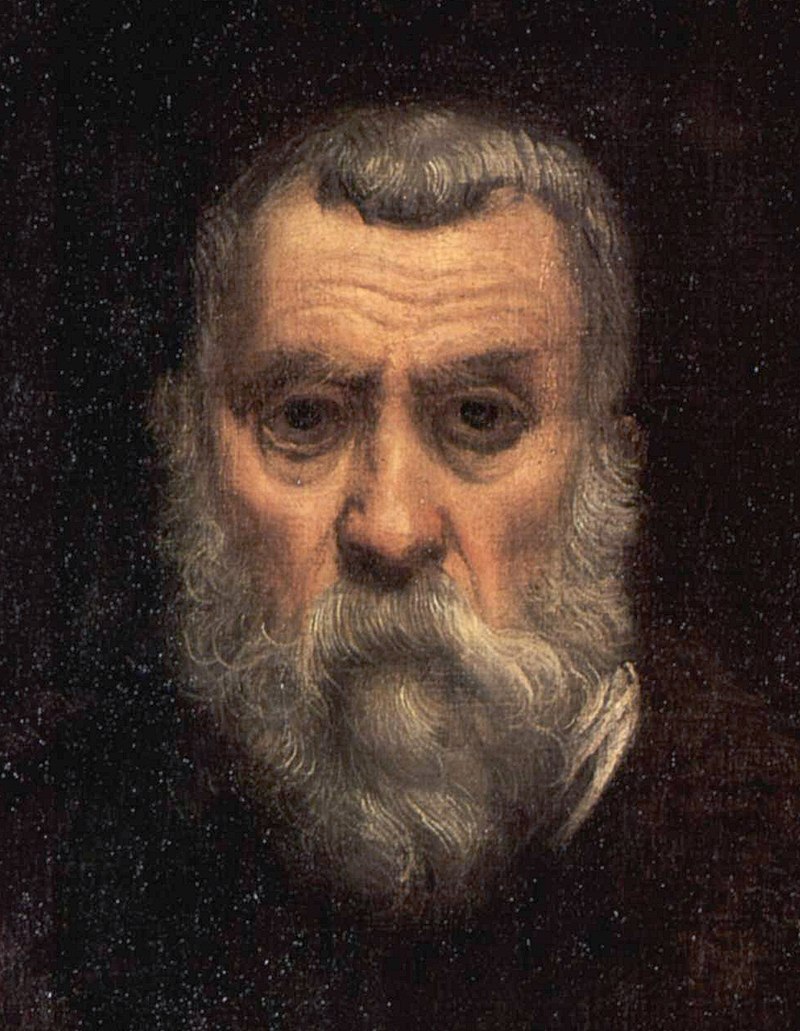

Battista Robusti, a dyer or tintore, in Venice, had a son in October of that year whom they named Jacopo. As their son grew, he acquired the nickname of Tintoretto, “little dyer”, or “dyer’s boy”. Tintoretto is known to have had at least one sibling, a brother named Domenico, and the family was believed to have originated from Brescia, in Lombardy, which was at that time part of the Republic of Venice. Tintoretto showed artistic talent from an early age, and by 1530 his father had guided him to the point where he thought that he had enough ability to become an apprentice to one of the many artists running studios in Venice. Battista had enough faith in his son’s ability to send him to work for probably the most influential and famous artist in Venice.

Tintoretto's self portrait in later life. Tintoretto's self portrait in later life.

Tiziano Vecelli was better known as Titan (pronounced tishan) and would have been around 30 years-old when young Tintoretto came to study under him. Titian’s father was superintendent of the castle of Pieve di Cadore and managed local mines for their owners, as well as being a distinguished councillor and soldier. His grandfather was a notary, as were many of his family, and they were well established in the area around Venice.

Titan had begun his training with Giorgione, but it soon became apparent that the novice had more talent than the teacher. Nevertheless, he continued working with Giorgione on several frescoes and from this distance in time it is difficult to distinguish who painted what. Their styles were so similar and they were constantly adopting improvements from each other. Giorgione died when still young in 1510, but Titan carried on with improving the new art moderna that they had championed. Michelangelo and Da Vinci, though still painting in their old style, were suddenly old school. Historians of art describe this period as the transition from High Renaissance to Mannerism. Needless to say Titan was in great demand, though his work showed the influence of his dead friend and rival with its bold and expressive brushwork. He was the rising star and darling of Venetian art.

Then along came young Tintoretto. The boy worshipped Titan, but for some reason, within the first few days, he incurred the displeasure of the master. The rejection of Tintoretto by Titan was catastrophic and final, and the boy was expelled from his studio. History has left no clues as to why this happened, but from then on Titan and his many followers disparaged Tintoretto relentlessly.

Poor Jacopo did not give up, and instead worked with craftsmen who decorated furniture with paintings of mythological scenes, and when not occupied with this, he practised his painting and studied alone. He was, for most of the time, penniless, but he had his own studio and he wrote his high ideals over the door. Il disegno di Michelangelo ed il colorito di Tiziano: Michelangelo’s drawing and Titian’s colour".

Tintoretto was not without friends, and he worked with Andrea Schiavone, who was gaining commissions for frescos. Tintoretto often worked for nothing, which needless to say attracted commissions, but most of his early work has been lost to time. Two more paintings which are lost, but are remembered only because Titan was recorded expressing his praise of the work, was a portrait of Tintoretto with his brother, and an unknown historical painting. Significantly, both works attracted the praise of the Venetian public. Some of his early paintings had been attributed to Schiavone, but recent scrutiny (2012) has revealed that The Embarkation of St Helena, The Discovery of The True Cross and St Helen Testing The True Cross, are works by Tintoretto. He was also gaining another reputation from his growing fans. People who saw him paint were amazed at the speed and ferocity with which he painted. He gained another nickname; Il Furioso; the furious.

The miracle of the slave. The miracle of the slave.

His big break came with a commission for a large fresco for the Scuola di S. Marco entitled the Miracle of the Slave. Tintoretto fully realised the significance of the opportunity, and spent hours composing the picture before he started painting. He made full use of the drama and theatre of the scene and used unusual colours applied with his, by now famous, vigorous execution. The painting was a resounding success, and brought him several commissions one of which was for the Church of San Rocco and called Saint Roch Cures the Plaque Victims. This would be the first of his many laterali paintings, in which he displayed an amazing grasp of off-centre perspective. When he painted these wall scenes he realised that the congregation would view the frescos from below and at an angle, so he elongated the scene so that, to them it, looked in perspective.

Saint Roch Cures the Plaque Victims. This picture has been digitally corrected, but the one in the church is foreshortened to the bottom RH corner for viewing by the congregation.

His next big break came in 1550 when he married Faustina de Vescovi, daughter of a Venetian nobleman who was the guardian grande of the Scuola Grande di San Marco. Faustina bore him several children, but his firstborn daughter, Marietta, attracted the gossips in Venice who rumoured that she was conceived before his marriage to Faustina. In any event, Faustina turned out to be a loving wife and a good housekeeper. Furthermore, Marietta turned out to be quite an accomplished portrait painter. Faustina brought him happiness and in 1564, more commissions for the Scuola di S. Marco: The Finding of the body of St Mark, the St Mark's Body Brought to Venice and St Mark Rescuing a Saracen from Shipwreck. But Tintoretti often did not get paid for his work. He was still well down the pecking order in the artists of Venice, and he sometimes offered to paint his frescos for nothing just to get his toe in the door. Faustina learned to be careful with her money, and when Jacopo went out she would wrap money in a handkerchief and expect a full account of his spending. Invariably he returned with empty pockets, explaining that he gave the money to the poor. He was an agreeable, witty person to talk to, but rarely smiled and he kept his work techniques secret. Sometimes he retreated to his study, where even his closest friends were not permitted to enter.

Titan, meanwhile, had gone from strength to strength, and by 1521he was nearing the peak of his career. His painting of St. Sebastian for the papal legate in Brescia brought him numerous commissions and numerous copiers of his works. He simultaneously produced The Death of St. Peter Martyr (1530), for the Dominican Church of San Zanipolo, and a series of small Madonnas like the Virgin with the Rabbit (Louvre). Titan, along with Giovanni Bellini, was commissioned to paint three large mythological scenes for Alfonso d'Este in Ferrara. Alfonso had created perhaps the most beautiful gallery of all time which gained fame as camerino d'alabastro (small alabaster room) in which he intended to hang the paintings of the most famous artists of the age.

For the camerino Titan produced The Bacchanal of the Andrians and the Worship of Venus (Now in the Museo del Prado), and Bacchus and Ariadne. (National Gallery London) Between 1530 and 1550 Titan and his studio artists were working flat out and his style was praised and copied everywhere. But he had neglected his contracts to paint for the Venitian government and they ordered him to refund the money they had paid him in advance. They asked his growing rival, Il Pordenone, to take his place. Pordenone died a year into the job, and a subdued Titan returned to honour the contracts. His material fortune was equal to Raphael and Michelangelo and in 1540 he received a pension from d'Avalos, Marquis del Vasto, and an annuity of 200 crowns (which was afterwards doubled) from Charles V from the treasury of Milan. He owned a villa in the Conegliano hills north of Venice, which is now known mostly for the production of wine, especially Prosecco. In 1546 he was given the freedom of the city of Rome. Four years later, he was summoned to Augsberg to paint Charles V and others. Whilst he was there, he painted the portrait of Philip II which was sent to Queen Mary of England, whom Philip later married. For the last 26 years of his life he worked for King Philip and mainly produced portraits of the nobility of Europe. At Philip’s request, he painted a series of large mythological paintings known as the poesie, mostly from Ovid, which scholars regard as among his greatest works. So many artists were copying his paintings that it’s difficult to separate the real ones from the fakes now.

The Black Death raged through Venice in 1576, and though he escaped the pestilence, Titan developed a fever and died in August that year. Soon after, his only son and heir, Orazio, died of the plague. Neither had thought to make out a will, and settling the estate of Titan took decades.

So, I hear you asking, where does the Last Supper come into this story?

Well, Tintoretto painted no less than 9 Last Suppers. Eight of them were in the style of Da Vinci, but the last was radically different. He swings the table around to create an offset viewpoint and then populates the canvas with a multitude of servants who are supplying the disciples with rich food, wine and fruits. But then he adds a host of unseen angels in the air around them, and you become aware that this instant is the defining moment of Christianity. Hardly the quiet supper after arriving in Jerusalem that the New Testament describes, but a painting which says that Jacopo was his own man, and that though self-taught, he could be counted with some of the finest artists the world has ever seen.

The Last Supper The Last Supper

The elders of Venice had not forgotten their other son, and twelve years after Titan’s death, they asked Tintoretto to paint a picture for the Dodge’s palace. He was 70 years-old by then, and he had no pupils, so he and his son, Dominico, painted Paradise together. The work is the largest ever oil painting on canvas at 74 by 30ft (22x7 meters) with around 500 detailed figures. It took months to complete, and when it was unveiled all Venice came to see it and praise the artist. He was told that he could name his price for the work, but humble Tintoretto asked just for his expenses during the work to be reimbursed.

Paradise Paradise

If you think that this is the end of the Last Supper you are wrong. It was a popular theme, and one which artists could use to further their careers.

2

Like

Published at 10:22 AM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 10:22 AM Comments (0)

How to gatecrash the Last Supper and end up in a mine

Saturday, January 23, 2021

A hundred and fifty-two years after the cathedral in Siena received its altarpiece, and 30 years before Leonardo was commissioned to paint his Last Supper, the Leuven Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament were in the process of building a new church which eventually became known as St. Peter's Church. They commissioned an Altarpiece from a 49 year-old Flemish painter called Dieric Bouts, who had moved to Leuven 13 years earlier.

Bouts may have studied under Rogier van der Weyden because his work shows that he was certainly influenced by him and Jan van Eyck, both leading innovators in the Early Netherlandish style typical of Bruges and Ghent. Dieric was from Haarlem, as was the architect of the church, Antoon I Keldermans. Both had probably been recommended by the church leaders in Haarlem, where they had achieved some fame for their work. The Last Supper was to be the central part of the altarpiece of the new church and was to become the first ever Flemish panel painting of the Last Supper.

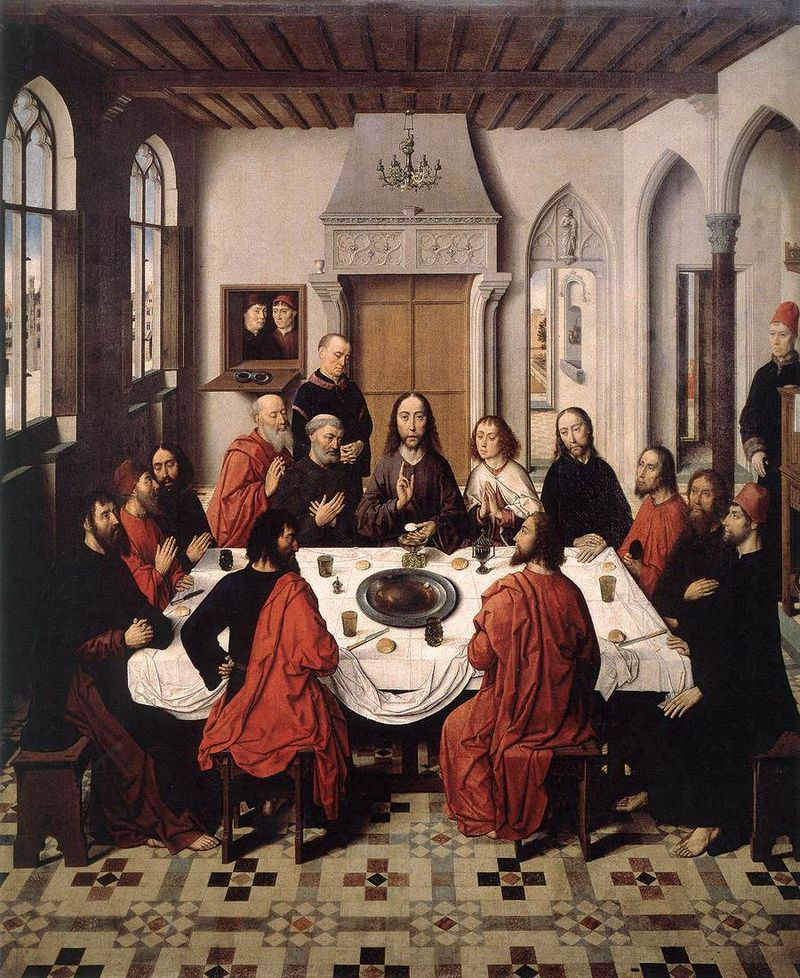

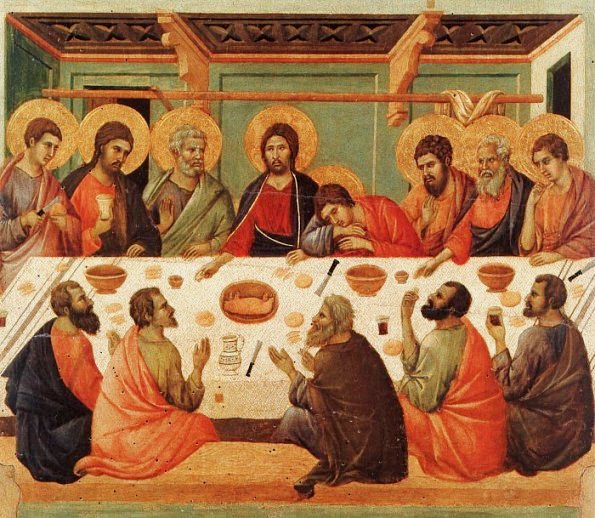

The central panel showing the Last Supper

However, the commission came with a long list of conditions. The Confraternity did not want the accepted scene of Christ’s revelation of betrayal; they wanted Christ in the role of a priest performing the consecration of the Eucharistic host from the Catholic Mass. Moreover, the two servants and some of the people who would have been painted as apostles were in fact portraits of local businessmen dressed not in the vogue of Jerusalem at the time of Christ, but in mid fifteenth century Dutch attire. To keep attention on the face of Jesus, the head of Christ is painted one-third larger than all the other faces, yet his face and some of the disciples are painted in a flat stylistic manner. However, those who paid to be included have quite good likenesses. Adding to this flagrant self-aggrandisement, the two faces in the serving hatch were the two priests who controlled the purse strings of the Confraternity, and who probably commissioned the painting. This just goes to show that even if you are a nondescript tradesman in a small town, you can elevate yourself to near martyrdom by buying an invite to Christ's last supper with his disciples.

Dieric’s painting of the Last Supper is also famous for its perspective, or to be more accurate, the mistakes in its perspective. Dieric was a student of Italian linear perspective, but he wasn’t too good at it. All the lines in the room should come to one vanishing point and Dieric decided to put his vanishing point in the middle of the lintel over the strange panelled doorway behind Christ. This high vantage allows you to look down on the table so that you can clearly see everybody sitting around it. But looking through the windows and open door, the horizon, which should also run through the vanishing point, is well below it. The side room on the right has a different vanishing point somewhere else, and the general effect is that of an architectural drawing rather than a work of art.

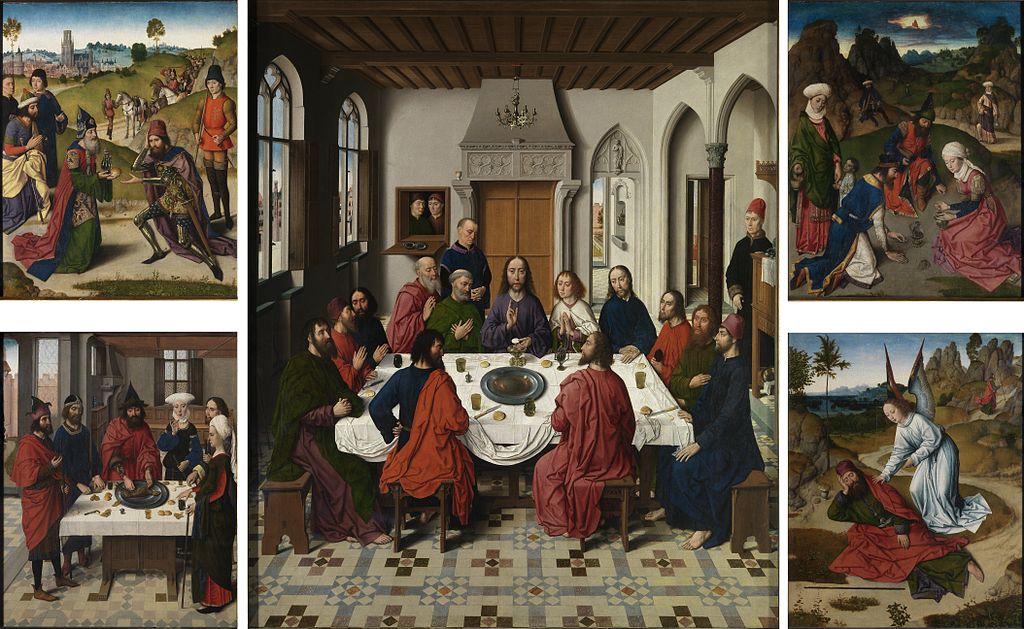

The panels shown in their original order.

Nevertheless, the full Altarpiece of the Holy Sacrament, as shown above, remained in St. Peter’s church, Leuven, until the late 1800’s, by which time the art world had lost interest in the early Dutch painters, and some of the side panels were sold to an antiques dealer in Brussels. They later turned up in the museums of Berlin and Munich. Shortly afterwards, the First World War swept across Europe, and when the carnage was over, the negotiators at the Treaty of Versailles demanded that Germany should return the panels to Leuven free of charge in reparation for the war.

And there they stayed until 1942, when the altarpiece was removed once again and taken to Germany. This is when life got really interesting for the Leuven Altarpiece of the Holy Sacrament.

When he became Reich Chancellor in 1934, Adolf Hitler had a dream of creating an art gallery in Linz, his home town. He wanted Linz to overshadow Vienna, where he had spent some unhappy years as a struggling artist. His dislike of the city stemmed not only from its strong Jewish influence, but because of his own failure to gain admission to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts.

Adolf is quite rightly vilified for his many other faults, but he initially established a fund from his own money to buy artwork to put in his proposed gallery. He used money from the sales of his book, Mein Kampf, profit from several property speculation deals, royalties from his image used on postage stamps and state birthday presents in the form of artwork. After a state trip to Rome, Florence and Naples in 1938 he was “overwhelmed and challenged by the riches of the Italian museums.” Hitler sent Heinrich Heim, one of Martin Bormann's adjutants, who had expertise in paintings and graphics, on trips to Italy and France to buy artworks.

After the Anschluss in March 1938, which brought Austria into the German Reich, both the Gestapo and the Nazi Party went on a spree of looting numerous artworks for themselves. Hermann Göring was chief culprit, and many of the purloined pictures ended up in his hands. In response, on 18 June 1938, Hitler issued a decree placing all artwork that had been seized in Austria be placed under the personal prerogative of the Führer. The order was to guarantee that Hitler would have first choice of the plundered art for his planned Führermuseum, and this later became a standard procedure for all stolen or confiscated art and became known as the Führer-Reserve. Because he was Hitler’s second in command, Göring was given control of the ERR, (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg für die Besetzten Gebiete) or The Reichsleiter Rosenberg Institute for the Occupied Territories. But when he thought Adolf’s men weren’t looking, he used it as his personal looting organization. At its peak, Göring’s art collection included 1,375 paintings, 250 sculptures and 168 tapestries.

On 21 June 1939, Hitler set up the Sonderauftrag Linz (Special Commission Linz) in Dresden and appointed Hans Posse, director of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Dresden Painting Gallery), as a special envoy. Hitler gave Posse a letter which ordered all Party and State services to assist him. By December 1944, Posse had spent 70 million Reichsmarks (equivalent to 261 million 2017 euros) on accumulating the collection intended for the Führermuseum. The acquisitions amounted to "technical looting," since the Netherlands and other occupied countries were forced to accept German Reichsmarks, which ultimately proved worthless.

Hitler's proposed art museum in Linz.

The artworks that Hitler collected were stored in a number of places, mostly in the air raid shelters of the Führerbau in Munich. But Göring's ERR had selected several estates for storage that were remote and unlikely to be bombed by the Allies. In 1943 Hitler ordered that these collections be moved. Beginning in February 1944, the artworks were relocated to the 14th-century Steinberg salt mines above the village of Altaussee, code-named “Dora” The transfer of Hitler’s Linz collection to the salt mine took 13 months to complete, and utilized both tanks and oxen when the trucks could not navigate the steep, narrow and winding roads because of the winter weather. The final convoy of art arrived at the mine in April 1945, just weeks before VE day. The salt mines usually had a single entrance, and a small gasoline-powered narrow-gauge engine was used to navigate to the various caverns. Into these spaces, workmen built storage rooms which boasted wooden floors, racks specifically designed to hold the paintings and other artworks.

In April 1945 Eisenhower gave up Berlin as an objective that would not be worth the troops killed in order to take it. He ordered the Third and Seventh Armies to turn south, towards what the Allies feared might be an "Alpine Redoubt" from which Hitler or fanatical Nazis could operate a guerrilla campaign.

From early on in the war, George Stout, a first World War Veteran working at Harvard's Fogg Museum, had been campaigning for a commission to be set up to catalogue the artwork that he knew was disappearing. American and British authorities were, needless to say, too busy with the war to listen. But in December 1944, the Allies created the Monuments, Fine Arts, and archives program. (MFAA) Stout was in the Navy working on aircraft camouflage, but was transferred the small corps of 17 “Monuments men” who were charged with cataloguing and recovering the missing artwork. They began to follow clues which led them all to locations in the area that Eisenhower had chosen to liberate last.

Captain Walker Hancock, the Monuments officer for the U.S. First Army learned the locations of 109 art repositories in Germany east of the Rhine by interrogating the assistant of Count Wolff-Metternich of the Kunstschutz. Captain Robert Posey and Private Lincoln Kirstein, who were attached to the U.S. Third Army, questioned Hermann Bunjes, a corrupted art scholar and former SS Captain who had been working for Hermann Göring’s ERR. Their information led them to Heilbronn, Baxheim, Hohenschwangau and Neuschwanstein Castle, where much of Göring’s loot was hidden. 1st Lt. James Rorimer attached to the U.S. Seventh Army had made contact with Rose Valland, a French resistance worker, who eventually shared the trove of information she had gathered at the Jeu de Paume museum while Göring’s ERR were using it as a store for stolen art.

The Monuments men. The Monuments men.

The gathering of the Monuments men became a frantic race when Hitler issued his Nero Decree shortly before the Russians overran Berlin. It called for all works of art to be destroyed in the event of his death or Germany falling to the Allies. Seemingly, Hitler had second thoughts about his decree and countermanded it, but after his suicide, the interpretation of his decree was left to officers in the field. August Eigruber, the Gauleiter of Upper Austria, had placed eight crates of 500-kilogram bombs amongst the artwork in the mine tunnels and he gave orders that they be wired and detonated.

The managers of the mine argued that the mine was their livelihood, and tried to remove the bombs. They were forced out of the mine by the Gauleiter’s troops who stood guard at the entrance whilst a demolition team set the charges. With the Americans just a few miles away, Eigruber fled with an elite SS bodyguard leaving his troops to finish the job.

Dr. Emmerich Pöchmüller, the general director of the mine, Eberhard Mayerhoffer, the technical director, and Otto Högler, the mine’s foreman approached Ernst Kaltenbrunner, an SS officer of high rank in the Gestapo who had grown up in the area and persuaded him to countermand Eigruber’s orders. They also persuaded the mine guards left by Eigruber to allow them to re-position the bombs so that they sealed the tunnel entrances without damaging the artwork inside. The plan took three weeks to execute, and on 5 May the charges were detonated. The Americans and the Monuments men arrived on the 8 of May and, aided by the mineworkers, frantically began clearing the entrance and bringing out the artwork. They removed the last pieces just before the Russians arrived.

If you haven’t seen the 2016 film, Monuments Men, you should watch it.

To finish the story, Dieric Bouts’ Last Supper was returned to Leuven when the war ended, and that’s where it remains to this day.

2

Like

Published at 9:57 AM Comments (4)

2

Like

Published at 9:57 AM Comments (4)

The seed of a legend germinates.

Saturday, January 16, 2021

The Last Supper did not originate with Leonardo da Vinci. It wasn’t even his idea. Somebody first painted it about 20 years after the crucifixion of Jesus, and it’s entirely possible that the artist could have been in the crowd that welcomed him into Jerusalem.

According to the New Testament, Jesus entered Jerusalem for the Feast of Passover and sent Peter and John ahead to meet a man who would show them to their accommodation. When they had rested from the journey, they all came together to eat. Jesus knew that he was in great danger, and it is very likely that he told his friends about his fears. During the meal that night, Jesus announced that he would be betrayed by one of his disciples. This caused consternation and howls of anguish from all of his friends. Jesus broke bread and gave it to his disciples, explaining that this was his body. He offered them wine, saying that this was his blood, and he charged them to spread his teachings after he was dead. This meal is the basis for the Eucarist, but is much better known as the Last Supper.

His betrayal, arrest, trial and subsequent crucifixion separated him from the Jewish faith, which stretched all the way back to Abraham. From now on, he would be the long awaited Messiah, the son of God. In the New Testament, Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians (11:23–25) has the earliest reference to the meal and dates from the middle of the first century, 20 years after the crucifixion. Matthew (26:17–29) gives a detailed description of the betrayal, but was written 30 years later. Mark’s (14:12–25) was 40 years later and Luke (22:7–38) 50 years later. Some of these accounts of the life and death of Jesus are hotly debated regarding origin and authenticity, but it is possible that what happened during the meal may have been elaborated upon when verbally passed on and spread amongst the early Christians shortly after Jesus’ death.

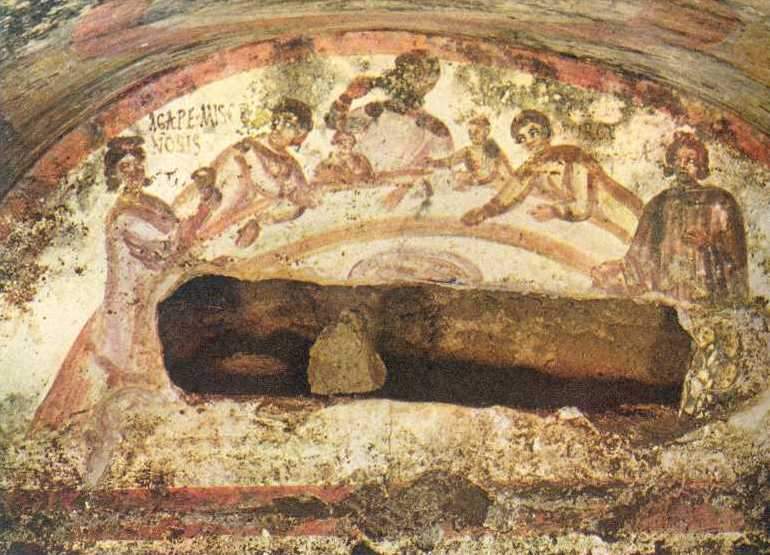

The first paintings of the last supper date from about the same time as Paul’s First Epistle, and they were found in the catacombs in Rome. The Fractio Panis fresco in the Catacomb of Priscilla on the Via Salaria is one of the most famous of catacomb paintings and it gives an idea of how early Christians took Communion. It is one of several from the first century CE and is the clearest example we have in catacomb art of the ritual of the Eucharist during the first two hundred years of the Gentile Church in Rome. In the New Testament book of Acts, (c. 63-70) there are references to Christians gathering to “break bread,” at what was called an “Agape Love Feast.” Considering that these figures are painted above an opening in the wall where a corpse was to be placed before bricking up the tomb, the paintings are more likely to show the poor soul attending a meal in heaven with Christ rather than a worldly event. Nevertheless, this was the first painting showing the concept of a Last Supper.

In the painting, seven people, one of whom is a woman, are reclining at a table where there is a cup of red wine and two large plates. One plate contains five loaves of bread, the other two fish, replicating the numbers in the multiplication miracle from the Gospels. A man at the left end of the table is breaking a small loaf in his hands. These pictures in the catacombs are the only illustrations of how early Christians of the first century after Christ’s death devoted themselves to the new religion, with baptisms and “breaking bread” in their homes, “with glad and sincere hearts.” (Acts 2:42 to 2:46) The catacomb paintings of Rome are the first depictions of a Last Supper, but we have to wait around 1,150 years before there is another painting of the Last Supper.

In 1196, the cathedral masons’ guild, the Opera di Santa Maria, was given the commission of the construction of a new cathedral in the city of Siena, which is about 50 km south of Florence. From the outset, this was designed to be a showpiece of art and sculpture that had no rivals. The architect /sculptor who directed the masons was Giovanni Pisano, whose work on the Duomo’s (The name of the Cathedral) façade and the pulpit was influenced by his father Nicola Pisano. His famous father had sculpted the pulpit in the Cathedral in Pisa, and it was he who was commissioned to sculpt the pulpit at Siena from Carera marble. Father and son worked together to build the west façade, which uses dark and white marble in horizontal stripes. This is the most impressive of the four façades of the Cathedral, with the middle of the three entrance portals overlooked by a huge bronze sun.

The Dumo Catherdral, Siena The Dumo Catherdral, Siena

Work was started on the north–south transept, and by 1215 the priests were already holding daily masses in the new church. The pulpit was finished and added in 1268, and is the oldest original work of art in the Cathedral. However, by this time Nicola had died sometime before 1284, and though Giovanni had taken up residence in Siena, he left abruptly in 1296 after falling out with the Opera di Santa Maria. He returned to Pisa, (His and his father’s home town.) and began working on their Cathedral.

I imagine that you are wondering what all this has to do with the Last Supper, well here is the link.

The altarpiece showing front on the left and the rear on the right.

In 1308, the Bishop of Siena commissioned the artist Duccio di Buoninsegna, a local artist, to paint an altarpiece for the cathedral. The front of the altarpiece showed the Madonna and Child with saints and angels. The reverse had panels showing the life of Christ and the life of the Virgin in 43 small scenes. The wooden altarpiece was mounted on a plinth, or praedella, on which were painted panels showing the childhood of Christ. The idea was that it could be seen from all directions when installed on the main altar at the centre of the sanctuary. At five meters high, it was a pretty impressive altarpiece for the time, and turned out to be the artist’s biggest commission and greatest work.

The construction of the altarpiece itself before painting was a complicated job involving the cutting, jointing and gluing of many frames and panels. The central panel alone was 2.1meters by 4 meters. When the carpenters had finished, it was left to Buoninsegna and his assistants to paint the scenes on the panels in his studio close to the cathedral.

On 9 June 1312, the altarpiece was unveiled and carried around the streets of Siena in a great circle before being installed in the cathedral. All the shops and workshops in the city were closed and the bishop commanded that all the high officers and devoted priests, followed by the population of Siena were to file past carrying candles. The cathedral bells rang and the poor received alms and the whole city prayed to the Holy Mother of God that she might “in her infinite mercy preserve this, our city, from every misfortune, traitor or enemy.”

One of the panels showing the life of Christ is this scene showing the last supper. Buoninsegna was occupied with the Maestà of Duccio as it became known, for at least two years and he was probably unaware that he was changing the style of art in the process. Until now, religious art had been very formalised and stylistic. Duccio, either deliberately or in haste, painted his scenes much more realistically. Church congregations in those days were mostly illiterate, and his depiction of the bible in everyday terms was very popular. Duccio became one of the most favoured and radical painters in Siena and his fame spread. Unlike many of the artists of the time, he painted in egg tempera and became a master in the medium.

Unfortunately, the local boy struggled with his own reality. There is little documentation concerning his life except for lists of unpaid bills. He is said to have been married with seven children, and when he died in 1260 his family disowned him because of his debts. His masterpiece fared a little better. The altarpiece remained in position for 465 years until it was decided to display it in pieces arranged between two alters. During the dismantling, many of the paintings were damaged and several disappeared or were sold. Some of the panels can now be found in in other museums in Europe and the United States. The panels that remain in Siena can be seen in the Duomo museum adjacent to the Duomo di Siena.

As we all know, this is not the end of the story for the idea of a last supper, or the artists who developed its potential.

0

Like

Published at 9:50 AM Comments (2)

0

Like

Published at 9:50 AM Comments (2)

When it’s OK to copy

Saturday, January 9, 2021

Sometime around 1450 the Duke of Milan, Francesco I Sforza, ordered the construction of a Dominican convent and church at the site of a prior chapel dedicated to the Marian devotion of St Mary of the Graces. Construction of the church took several decades, and when Francesco died in 1466, his son Duke Ludovico Sforza decided to have the church serve as the Sforza family mausoleum. He rebuilt the cloister and the apse, both completed after 1490, and he added a mortuary chapel adjacent to the cloister. The Duke decided to have the walls of the mausoleum decorated with biblical scenes, above which he wanted to have painted the Sforza coat of arms. For this task he employed a 38 year-old artist called Leonardo, who had studied in the studio of the renowned Italian painter Andrea del Verrocchio and was gaining a reputation as an artist. Leonardo’s origins were not auspicious. He was born out of wedlock to a notary, Piero da Vinci, and a peasant woman, Caterina. They both lived in the Tuscan town of Vinci, in the region of Florence, and Leonardo became known as Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo was allowed a free hand in how he depicted his scene, but it seems likely that the Duke chose the subject of the Last Supper. Around 1495 Leonardo began preparing the wall of the mausoleum for painting. He decided to paint in the fresco style with oil and tempera paints. Da Vinci used experimental techniques on the painting. Instead on painting in the buon fresco style (applying pigments to wet plaster), Leonardo used a style known as a secco (painting on dry plaster). Because he painted on the dry plaster, the colours did not blend into the surface as well. This caused the painting to be much more fragile and led to its rapid deterioration.This was compounded by the fact that the other side of the wall was open to the often wet and sometimes freezing weather of Northern Italy, causing condensation and damp.

The opposite wall of the mausoleum was covered by a fresco by Giovanni Donato da Montorfano showing the Crucifixion. Leonardo was asked to add figures of the Sforza family in tempera to the other fresco, and these figures deteriorated as quickly as his Last Supper. The work dragged on over three years, and there were long periods when Leonardo was absent. He was berated by a prior in the monastery who had been complaining to the Duke about the length of time Leonardo was taking over the painting, and an irate Leonardo told the prior that if he didn’t shut up he would paint his face on the figure of Judas.

The deterioration of the painting continued. Sixty years after Leonardo had finished the painting, the figures were unrecognisable, and 150 years later there was little evidence left that there had ever been a fresco painted on the wall, and a doorway was cut through which obliterated Christ’s feet. The greatest Last Supper of all time, painted by the greatest genius of the century was lost forever.

The now restored Last Supper in the Santa Maria delle Grazie

Leonardo de Vinci was tutor to many students who later followed his style. In the list of members of his studio that he kept, Leonardo mentions an artist called Giampietrino. This is a nickname, and scholars have struggled to ascertain the real name of the artist. It’s important because it was Giampietrino who helped Leonardo paint the Last Supper in the Santa Maria delle Grazie.

When Leonardo’s patron, Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, was deposed by the French in 1500, Leonardo fled to Venice where he was employed as a military architect and engineer. He spent the next six years in a number of roles, but he was given several important artistic commissions, one of which was a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo. In 1506 he was summoned back to Milan by the acting French governor of the city, Charles II d'Amboise. Upon his return, he took on another young pupil, Count Francesco Melzi, the son of a Lombard aristocrat, who later on became Leonardo’s secretary and lifelong friend.

During his earlier travels, Leonardo had been accompanied by a young man whom he had taken under his wing at the age of 10 as a garzone (studio boy) in the workshop. Now known only as Salaì, (little devil) he was the son of Pietro di Giovanni, a tenant of Leonardo’s vineyard near the Porta Vercellina, Milan. Leonardo sometimes used him as a model for his paintings, but he was an unruly boy and Leonardo described him as, “A liar, a thief, stubborn and a glutton.” after he had made off with money and valuables on at least five occasions and spent a fortune on clothes. Nevertheless, Leonardo kept him in his household for more than 25 years, and though he produced several copies of Leonardo’s paintings, (including a nude Mona Lisa) Salaì’s work is considered inferior. Leonardo’s sex life is very obscure, but it’s significant that there were never any women in his life.

By1508, Leonardo was back in Milan, living in his own house in Porta Orientale in the parish of Santa Babila. It was probably during this time that Melzi worked with Leonardo on the unfinished portrait of Lisa del Gioconda. Apart from all his other achievements, Leonardo will be remembered primarily for the Last Supper and the Mona Lisa, which was copied whilst Leonardo was alive, and probably with his guidance and approval. There are two paintings of the Gioconda in existence. The first is hanging in the Louvre, and is attributed to Leonardo. The other is in the Museo del Prado, Madrid and only came to be recognised for what it was when restorers began cleaning it. Exhaustive tests revealed that the second was painted at the same time as the first, and the most likely second artist was Melzi, Leonardo’s favourite student. However, nobody had yet copied the Last Supper.

During his second stay in Milan, it seems almost inconceivable that Leonardo did not return to Santa Maria delle Grazie and inspect his Last Supper painted 13 years earlier. He would have seen the paint and plaster peeling and realised that his masterpiece was doomed. It’s hard to say how he felt, but he was busy with so many things in his life that he probably had no time to do anything about it. Giampietrino, the student who had helped him paint it, was still living in Milan, and was a famous artist in his own right with a multitude of commissions from prominent figures of the aristocracy. But they were both together in Milan for around 7 years. Another of his old students was doing quite well, too. Andrea Solari followed Leonardo’s style, and was also working on a sizable number of commissions. Both of these artists frequently copied Leonardo’s paintings.

Then fate stepped in, and during October 1515, King Francis I of France recaptured Milan and a year later, Leonardo entered Francis’ service, being given the use of the manor house Clos Lucé near the king’s residence of the royal Château d’Amboise in the Loire valley. He was given a pension of 10,000 scudi, and he was accompanied by Salaì and Melzi who also received pensions. It was during this time that Leonardo suffered a stroke that paralysed his right arm and stopped him from painting. More than one chronicler proposes that this is why he never finished the Mona Lisa. Leonardo died at Clos Lucé on 2 May 1519 at the age of 67.

Meanwhile, in Milan around 1520, Giampietrino began painting an exact size-for-size copy of Leonardo’s Last Supper in the Santa Maria delle Grazie, but this time in oils on canvas. At virtually the same time, Andrea Solari, began another full-size copy of the Last Supper in oils.

To my mind, there are two ways to look at this. Both Giampietrino and Solari waited for Leonardo to die before copying his Last Supper, knowing that the original would soon be obliterated and they could vie to claim credit for the work. Or, during the time that Leonardo lived in Milan, he collaborated with his old pupils and helped them copy it so that it would not be lost. Giampietrino and Solari were already famous artists; they did not need to claim the Last Supper as their own. I would like to think that they copied it to preserve their old master’s masterpiece for posterity.

One thing is for certain, were it not for these copies, Leonardo’s Last Supper would have faded on the wall and been forgotten. If ever there was a good reason to copy another’s work this surely qualifies.

Over the centuries, the Last Supper in the Santa Maria delle Grazie has had six attempts at restoration, and one failed attempt to remove it in its entirety to a safer place. It was vandalized by French troops, bombed by the allies during the Second World War, (Which I suppose can also be classed as vandalism.) and finally restored in 1999 to the painting we see today. That it survived at all in its present form is a tribute to all those people over the centuries who tried to restore, protect and preserve it, but without the two copies, nobody would have known what the original looked like.

The cut-down Last Supper painted by Giampietrino

Giampietrino (Scholars of the art world now believe that Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli was the real name of Giampietrino.) went on to promote Leonardo’s style, and produced over 70 paintings which are hung in 47 museums or private collections around the world. The copy of the Last Supper that he painted now hangs in the Magdalen College, Oxford, and is part of the collection of The Royal Academy of Arts. Sometime after the copy had been made, the top third and the ends were sliced off of Giampietrino’s painting. Solari’s painting is still full-size, and is hanging in Tongerlo Abbey in Westerlo, near Antwerp.

_-_WGA12732 Salzi.jpg)

The full size Last Supper painted by Solari

Over the centuries, Leonardo’s The Last Supper has become the most copied painting of all time, but Leonardo was not the originator of the idea of a Last Supper, nor is he the only one to exploit a theme that had many uses.

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|