Isabel of Castile’s youngest daughter, Catherine, was betrothed to Arthur, the Prince of Wales, the son and heir of Henry VII of England. The marriage had been arranged when Arthur was only three and Catharine two. It was a high-profile agreement between two nations designed to cement an alliance between Spain and England against France. The Treaty of Medina del Campo was a bold plan by Henry II Tudor, who had ousted the Plantagenet line at the Battle of Bosworth Field, and was worried about the many more rightful claimers to the throne of England still alive. Of the twenty six clauses in the treaty, seventeen covered economic trading deals and military agreements, only one was about the marriage, the rest were negotiated rights following the wedding. Catherine’s dowry was fixed at 200,000 crowns (Over £5 million pounds in present day values.) and both parties happily signed the contract. After this, things started to become more than a little silly.

Cathrine of Aragon.

Cathrine of Aragon.

Arthur’s father was a great believer in the legend of King Arthur of the round table, and at that time legend had it that Worcester was where the fabled court of Camelot had been. He built a manor house there, and took his wife to have his child there, so that his son would be born in the same place that King Arthur ruled from. When she had a boy, Henry was overjoyed and called his son Arthur in anticipation of a golden future ahead for the child.

Arthur

Arthur

Before the children were of age a request was sent to the Pope for a dispensation to marry them even though they had never met, and were still far too young to be considered a husband and wife. The Pope duly sent his blessing and they were married by proxy in 1497 at Arthur's home, Tickenhill Manor near Worcester. Eleven year old Arthur was reported to have said to Roderigo de Puebla, the Spanish proxy for Catherine that “He much rejoiced to contract the marriage because of his deep and sincere love for the Princess.”

The young couple wrote to each other in the common language of Latin for four years until on the 20th September 1501 they were deemed old enough to live together. Arthur was 15 and Catherine was 14. Catherine arrived at Plymouth on the 2nd of October and a month later, the children met each other for the first time at Dogmersfield in Hampshire, and immediately discovered that they had been taught different forms of Latin and could not understand each other. Despite this setback, they eventually rode to London to be married.

On 14 November 1501, the marriage ceremony finally took place at Saint Paul's Cathedral; both Arthur and Catherine wore white satin and the ceremony was conducted by Henry Deane, Archbishop of Canterbury, assisted by William Warham, Bishop of London. Following the ceremony, Arthur and Catherine left the Cathedral and headed for Baynard's Castle, where they were entertained by "the best voiced children of the King's chapel, who sang right sweetly with quaint harmony."

Arthur’s mother, Margaret Beaufort, was a party to the next bout of insanity when Catherine was led away from the feast and undressed by her ladies-in-waiting. They veiled her and placed her in the nuptial bed, which had been sprinkled with holy water beforehand. Arthur was led in escorted by his gentlemen friends, to the accompaniment of viols and tabors, with no less a dignitary than the Bishop of London, who blessed the bed then led everybody from the room. In royal weddings, this was a not uncommon thing but this was probably the only public bedding recorded in Britain during the sixteenth century. Needless to say, the marriage was not consummated that night.

The following morning, the poor boy had to brag to all the courtiers of his prowess in bed. Whether the marriage was eventually consummated can only be known by the royal family, and later events would make the falsification of Catherine’s virginity highly desirable. The couple took up residence in Ludlow Castle in Shropshire where they both fell ill with the sweating sickness, a contagious disease that first appeared in 1485 and spread throughout England and Europe. The symptoms appeared rapidly and often caused death within hours. It effected rural areas the worst, and unlike other epidemics, spiked quickly before disappearing. Catherine survived the chills, body pains debilitating weakness and fever, but Arthur did not. He died on April 2 1502.

With his carefully laid plans in disarray, a heartbroken Henry VII now had to pass his title on to his second son, also named Henry. However, the trade treaty with Spain that a marriage to Catherine would bring was too important to lose. Catherine was now 17, but Prince Henry was only 11 years-old. To continue with the lunacy seemed reasonable, so Catherine was betrothed to little Henry. Catherine would need to be still a virgin in order to be married again, and she always claimed that she was. Isabel and Ferdinand were more than a little dubious of the marriage arrangements, but they feared the French, and an alliance with England was much desired, and so, the betrothal of Henry and Catherine went ahead.

Isabel knew all about the onerous duties of royalty from her own experience, and she had given Catherine advice and guidance. The two women corresponded continuously, but the loss of Juan had drained Isabel’s spirit. The constant wheeling and dealing with the fate of her family must have been a strain over the years and in November 1504, Queen Isabel died. She never saw Catherine crowned Queen of England, but for a while her other daughter, Joanna, became Queen of Castile with King Ferdinand as Governor and Administrator. Ferdinand was occupied with the growing discoveries and trade and with the new colonies in the Caribbean, and in April 1505 Columbus docked in Sanlúcar from his fourth and final voyage to discover that his patron was gone and he would have to deal with King Ferdinand or the unstable Joanna. He was still owed considerable money under the terms of his 1492 agreement, and he and his family were to sue the crown for payment for years to come.

Ferdinand married again to Germaine of Foix in March 1506 in the city of Valladolid where he had established his court, and a by now terminally ill Columbus followed him there on the back of a mule to continue with his demands. On 20 May 1506 Christopher Columbus died. In fourteen years he had transformed the world. But Queen Isabel’s legacy of change and expansion was still to be fulfilled, and so was Columbus’ belief in a westward route to China.

In 1509, five years after the death of Isabel, Henry VII died and Prince Henry became King Henry VIII, and the English crown was secure again. Twenty-five years-old Catherine married 19 years-old Henry. On June 15 of the same year, Catherine was crowned Queen of England alongside Henry in an extravagant joint coronation ceremony at Westminster Abbey. On their nuptial night Catherine discovered that Henry was nothing like his brother. Henry thought the now slightly plump Catherine was the most beautiful thing he had ever seen. His ardour was unquenchable. Not unexpectedly, she was pregnant within a few weeks.

Bad luck dogged Catherine all her life. She was a noble queen and a loving wife, but she failed to give Henry the one thing he needed most. Her first child, a girl, was stillborn on Jan 31, 1510. She kept the almost painless birth a secret because Catherine’s abdomen was still large, and it was thought that there was another child within her. Henry knew, of course, and he and Catherine’s two ladies in waiting were sworn to secrecy. Finally, as her abdomen returned to normal, it was realised that there was no other child. Catherine’s confessor, Frey Diego, wrote to her father, King Ferdinand, the following May to tell him of the loss. There would be other pregnancies, but the only child to survive was a girl called Mary who was born on February 8, 1516. She would fight similar battles to her grandmother’s on English soil to claim her birthright as the Queen of England, but bad luck followed Mary as it did her mother, and her womb refused to produce a male child when she married Philip II of Spain. Had it done so, England would have returned to being a Catholic country and become a part of the greatest empire the world had ever seen, and Mary’s step-sister, Elizabeth, would never have become queen of England; how this would have affected world history is incalculable.

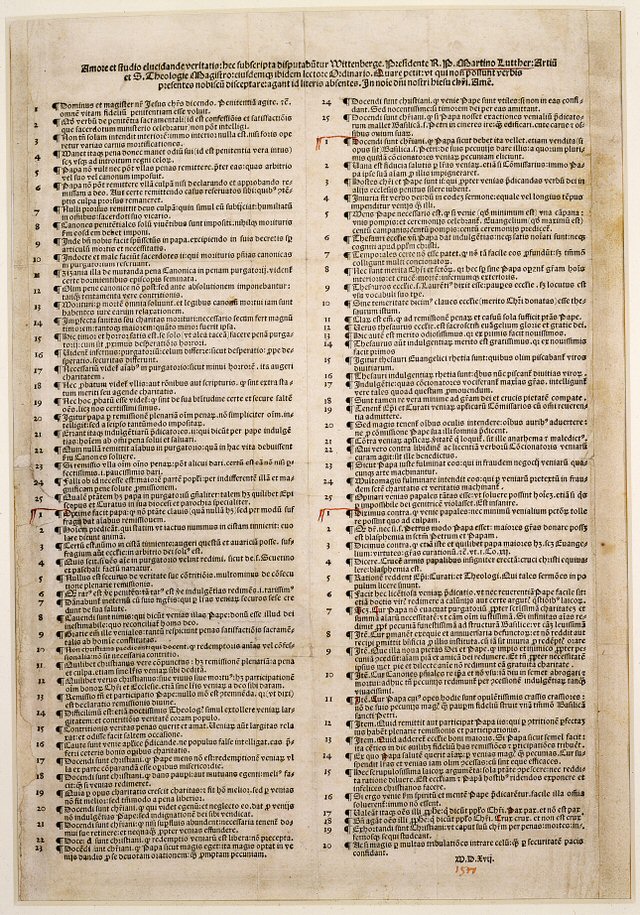

Catherine’s inability to produce a male child would bring a catastrophic change to England and the death of thousands. The genesis of this calamity lay in the hands of a German priest who was ordained in 1507. He became disillusioned with the Catholic Church and ten years later he nailed his proposals for its reform on the church door at All Saint’s Church along with several other churches around Wittenburg. (This was an accepted way of inviting discussion within the church.)

The 95 theses of Lutherian reform.

The 95 theses of Lutherian reform.

He also published a sermon in German that all could read. At this time, the first printing presses were being used for posters and books, and Luther had his thoughts printed for publication. The sermon he printed can be read aloud in ten minutes, but it became a best seller with sixty thousand copies sold all over Christendom.

Luter pinning his thesis to the church door. Unknown artist.

The Church was furious, and Pope Leo X and the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, excommunicated Luther. He was escorted out of town, but friends intercepted the carriage, and he was spirited away to safety. By 1522, and still in hiding, Luther had translated the Bible into everyday German from Hebrew and Greek making it more accessible to the laity.

Henry VIII had been told about Luther’s bible and he was prompted to denounce it and back the Pope. Henry wrote his own book and had it published in which he re-affirmed the seven sacraments, or seven stages of the soul through life to heaven. The Pope was so pleased with Henry’s devotion that he granted him the title “Defender of the Faith,” a title which all British Kings or Queens still carry.

The printed works of Luther and Tyndale were being shipped clandestinely into England and Cardinal Wolsey ordered their collection and burning before the doors to the old St. Pauls Cathedral. The power of the Catholic Church in England was being undermined by the reproduction of a bible that all men could read. The clergy knew that real danger was that everybody could see that the Catholic Church had been distorting the true meaning of the faith for centuries.

Henry had been casting a roving eye around his court, and had his choice of young girls. Early that year, a young girl of 15 years came to take up a post as maid of honour waiting on his wife. Anne had a striking beauty and her sophisticated manners earned her many admirers at court. Although she resisted Henry VIII's advances, by 1533 Anne was pregnant to Henry. This is just what Henry had been waiting for. He appealed to Pope Clement VII for an annulment to his marriage to Catherine so that he could marry Anne. The Pope was afraid to go against the will of Catherine's nephew, Charles V, The Holy Roman Emperor, and refused his plea.

When she came to Henry’s court, Anne brought with her a book written and published in Antwerp by William Tyndale entitled “The Obedience of a Christen man, and how Christen rulers ought to govern.” Henry had condemned Tyndale and his Bible, but here was his pretty lover with a book that told Henry that Kings were accountable only to God and not the Pope. She had underlined the passages that she wanted Henry to read. When he had finished, he remarked that “This Book is for me and all kings to read.” Henry had seen the lesson in Leviticus. “And if a man shall take his brother's wife, it is an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother's nakedness; they shall be childless.” He believed that by marrying his brother’s wife, Catherine, he had cursed himself to childlessness.

Catherine pleaded with Henry not to divorce her, saying that her marriage to his brother had never been consummated. With Anne pregnant with a possible male heir, Henry was backed into a corner. He made his decision and broke with the Catholic Church. He passed the Act of Supremacy, declaring that he was the head of the English Church and appointed Thomas Cranmer as Archbishop of Canterbury, who immediately annulled the marriage between Catherine and Henry and announced the wedding of Ann and Henry. In June 1533 Anne was crowned Queen of England in a lavish ceremony at Westminster.

The dynasty of Queen Isabel was not over yet, and already the religious world had been split down the middle, but the next century would see that her joining of León, Castile and Aragon into one kingdom would eventually raise Spain to superpower status.