Omar ibn Hafsun

Saturday, August 29, 2020

The final years of his reign must have been bitter for Al Rahman III. He faced rebellion from all quarters, not least from a new adversary who had none of the lineage of centuries of rule in the lands of the Bible that the caliph had.

Omar Ibn Hafsun was born near to Parauta in the mountains near in what is now Málaga sometime around 850. His origins are obscure. One of his contemporaries refers to him as a descendent of black Africans, but another historian writing a hundred years later claims that his lineage went back to Visigoth kings. It is entirely possible that the second version was invented by Ibn Hafsun himself and passed on to posterity.

Omar ibn Hafsun. Omar ibn Hafsun.

Hafsun was an unruly boy, and soon involved himself with the wrong kind of people. He joined a group of brigands, and soon gained notoriety among the criminal and disaffected elements of the area. He had a violent temper, and he settled his disputes with the sword or knife. Before he was 30 he had become a murderer, and was arrested along with a group of other brigands in the Málaga area. The governor of Málaga was unaware of the murder charge, and fined him and the other thieves. They were released, and Hafsun fled to Morocco on the first ship. When the authorities found out, the governor was dismissed from his post. Hafsun laid low for a while working as a tradesman, and it was during this enforced hiatus that (according to the legend) he met an old man who told him to return to al-Andalus, where he would become a king and a leader of armies.

In 880 he did return to Málaga, and aided by his uncle, he joined a group of 40 other Christians, muladíes and Berbers, who were prepared to fight against their haughty Arab overlords. They decided to hide in the mountains and gorges of Alto Guadalhorce near to the town of Ard-Allah. (Ardales) It was here, in a place that was almost inaccessible, that they built Bobastro as their base from which to conduct guerrilla warfare against the forces of the caliph. They enlarged their domain by fortifying Ard-Allah and then capturing or inciting rebellion in local strongholds and towns.

The ruins of Bobastro. The ruins of Bobastro.

At first, the caliph considered them nothing more than a group of bandits, but in 882 when Hafsun formed an alliance with the King of the Basques, García Íñiguez, in a revolt against him, he realised that Hafsun was a man to be reckoned with. He was forced to send an army to Pamplona to put down the rebellion, and the armies met in battle near the town of Lumbier. The result was a crushing defeat for the rebels. Hafsun escaped and returned to Bobastro, but Íñiguez was killed.

When the caliph realised that Hafsun controlled towns and swathes of land around Cádiz, Jaén, Seville and Granada, and had allied himself with the populations of Archidona, Baeza, Úbeda and Priego, he began to pay careful attention to Hafsun and his followers. He sent his generals out to hunt him down, and eventually large force of the caliph’s army caught up with Hafsun and his men.

Hafsun saw a likely defeat and began negotiating a truce with al-Rahman. In return for the acknowledgement of the rights of his followers, and permission to live in peace with respect, he promised his obedience to the caliph. Hafsun fought several battles with the emir’s general, Hashim ibn Abd al-Aziz, and won the respect and praise of the caliph’s soldiers with his intelligence and courage. When he rode through Córdoba he was cheered by the crowds, and the caliph granted him the governorship of the Cora province with its capital in Archidona. Al Rahman invited him back to Córdoba and asked him to be his bodyguard. His loyal followers were to be the caliph’s guard of honour.

Things were going well for Ibn-Hafsun, but there is a saying that you can take the boy out of the gutter, but you can’t take the gutter out of the boy. The haughty Syrians who had elevated themselves to high positions in the governance of al-Andalus were not about to let this near barbarian and his crowd of rabble-rousers take over the city. Hafsun and his men were snubbed, humiliated, cheated and ridiculed. Everything that they were promised by the caliph was denied them.

In disgust and anger, Hafsun and his men returned to Bobastro and renewed their battle against their Arab lords. He seized the fortresses of Comeres, Mijas and Autha and formed alliances with other rebel groups which gave him control of a large part of southern al-Andalus. Al-Rahman now realised that he must quell Hafsun’s rebellion. He gave his sons, al-Mundhir and Abd Allah, command of his army and sent them out to put an end to his rampage. In 885 Hafsun moved his headquarters 80km north of Bobastro to the town of Poley, so that his forces could respond quickly to any threats.

The following year, (886) al-Mundhir surrounded Hafsun and his followers, who had allied themselves with another band of rebels, the Banu Rifá, in the town of Alhama, near to Granada, where he laid siege to them. The siege was beginning to take its toll on the rebels’ troops when news came that al-Rahman III had died. Al-Mundhir was forced to return to Córdoba to take over running al-Andalus. But Hafsun was not off the hook. Al-Mundhir wasted no time in organising successful assaults against Hafsun’s strongholds. His army drove Hafsun back and took Archidona, where the caliph ordered that the chief of the Christian rebels be crucified alongside a pig and a dog.

Luck was with Hafsun again in June 888 when he was besieged at Bobastro by the two brothers who had cut off all supply routes to the citadel. The siege was taking effect when al-Mundhir died. His brother, Abd-Allah, concealed his death for three days hoping that Hafsun would capitulate, but he had to raise the siege and return to Córdoba to take control of the caliphate. The retreat by Abd-Allah was now effectively a funeral cortege as they took the body back to Córdoba.

When Hafsun learned of the death, he sent his men out to loot the camp of his besiegers and chase the caravan of mourners. Abd-Allah sent the rebel leader a message to respect his dead brother, and to his surprise, Hafsun called his men off. The new caliph sent a train of 50 mules loaded with food and finery to Bobastro in gratitude, but Hafsun took the presents and continued his war against the new caliph. A furious Al-Mundhir sent back the message that he would be proclaimed caliph over al-Andalus over the dead bodies of the rebels at Bobastro.

Hafsun strengthened his alliances with other disaffected groups around Córdoba, Seville and Jaén. He captured Estepa, Osuna and Ecija in 889. At Baena he massacred the defenders causing Priego and all the towns around to surrender without a fight. By 891 the land under his control stretched from Jaén in the east to Seville in the west. To seek official legitimacy he began to collect taxes and sent emissaries to the Tunisian Aglabis who recognized the Baghdad caliph and then, when they were ousted, with their conquerors the Fatimíes, even though they were they were Shiites and most of al-Andalus were Sunnis. To show that the part of al-Andalus that he controlled was open to all religions he allowed Shiite imams to preach from Mosques controlled by Hafsun.

Hafsun suffered a crushing defeat in 981 when the lost a crucial battle against the caliph, al-Mundhir (now Abdullah ibn Muhammad al-Umawi) at Poley. Hafsun escaped, but the caliph ordered the massacre of all the Christians in Poley, and Hafsun was forced to move his headquarters back to Bobastro.

In 899 Hafsun made a mistake that lost him much of his support. In an effort to ally himself with the Caliphate of Córdoba’s biggest enemy, the Asturian King Alfonso III, Hafsun converted to Christianity and was baptised, taking the name of Samuel. He converted the small mosque at Bobastro into a Christian church and installed a Bishop.

Immediately he lost around half of his supporters. The Berbers and Arabs, his strongest followers, abandoned him. His respect and fame allowed him to continue for a few years more, but his hoped for ally, King Alfonso III, capitalised on Hafsun’s losses and made pacts with those disaffected with him. At the same time, the caliph of Córdoba was relentlessly eating into lands and towns under Hafsun’s control.

In 917 Hafsun died and was interred at Bobastro. His coalition crumbled and for a while his sons tried to maintain resistance, but Bobastro fell in 928 and the troops who had fought for Hafsun were absorbed into the armies of the caliph and sent to fight against the Galicians.

Hafsun’s remains along with the bodies of his dead sons were crucified and put on display outside the Great Mosque of Córdoba.

The golden age of al-Andalus was about to reach its glorious zenith. The first stones were being laid for the Shining City, which would become the cultural masterpiece of al-Andalus; but it was built on sand. Medina Azahara would only last for 70 years before it was sacked, abandoned and destroyed. Disputes within the caliphate led to civil wars, and caliphs came and were deposed or died with astonishing regularity, some of them only lasting a year. There were 16 caliphs between 929 and 1023.

But the doom of al-Andalus was decreed by an event in the homeland of its Arab rulers. In 1070 the Seljuk Turks had taken Jerusalem and began a systematic torture of the Christians who lived there. By 1095, the situation had become so bad that Byzantine Emperor Alexios I sent his envoys to Pope Urban II with an urgent message, asking for help from western Christians to liberate the region from the infidels. The pope gave a historic sermon at the Council of Clermont and urged the knights, princes and people of the Western Roman Empire to take up arms and to embark on the journey to "liberate" Byzantines or Eastern Christians from the "pagan race."

He said that "whoever for devotion alone, not to obtain honour or money, sets out to liberate church of god in Jerusalem, this will be counted for all his penance." The appeal by the Pope marked the beginning of the First Crusade. The incentive to drive Islam from Iberia had become a holy war.

2

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (8)

2

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (8)

Uneasy lies the head.

Saturday, August 22, 2020

The Abbasids had taken control of all the Muslim lands along the southern shores of Mediterranean by 750, creating thousands of homeless Umayyad refugees. In a generous gesture, the Fihrid family welcomed them and allowed them to settle in al-Andalus. These were the sons and grandsons of Caliphs, and had a more valid claim to al-Andalus than the Fihrids. The ingrate newcomers aligned themselves with the disenchanted lords under Fihrid rule and rose up against them.

In 756 the Umayyad prince Abd al-Rahman I overthrew the Fihrid family and established himself as Emir of Córdoba. He held the title for thirty years, despite his rule being constantly challenged by the al-Fihri family and the Abbasid Caliph. It was Abd al-Rahman I who ordered the conversion of the Visigoth church in Córdoba into a mosque and laid plans for further construction and enlargement. The mosque was considerably extended by his successors over the next hundred years to become the Great Mosque of Córdoba that we know today.

When he died in 822 his son became Emir of Córdoba as Abd al-Rahman II. His reign was far from peaceful, and from the first day, King Alfonso II of Asturias began a campaign against the new emir that lasted 23 years. After many costly battles, he finally halted the advance of Alfonso by building the citadel of Murcia and populating it with loyal Arabs. He had to do the same at Mérida in 835 to hold down a revolt there. In 837 he suppressed an uprising of Christians and Jews in Toledo using the same measures.

As if this was not enough to contend with, in 844 he had to fight off an invasion by Vikings, who had taken the harbour at Cádiz (though not the fortress), and marched on to take Seville. He only managed to drive them back when they were at the gates of Córdoba. From then on, he had to strengthen his navy and patrol the entire west coast of Iberia to counter the Vikings, who continued making raids through the straits and as far as the Balearics. They also attacked North Arica, and he was obliged to protect his assets there, too.

Under Muslim rule, Christians could retain their churches and property on condition of paying a tribute (jizya) for every parish, cathedral, and monastery. But the ruling Arabs were not without compassion. The Christians and Jews found themselves beneficiaries of a society that supported the old and infirm, as well as the blind, crippled and those forced to live on the streets begging. The Jews had suffered persecution under the Visigoths for centuries, and now they were free to worship as they wished, sharing equal rights with the Christians. Many of the Christians converted to Islam simply to avoid paying the jiya.

But there were a few caveats to Muslim rule that the Christians were unhappy with. They and the Jews had to abstain from any public displays of their faith in the presence of Muslims, as such an act was considered blasphemy under Islamic law and punishable by death. They were also forbidden to actively try to convert Muslims to another faith. The unrest of the Christians erupted into civil disobedience in early 851. The emir at first ordered the arrest and detention of the clerical leadership of the local Christian community.

When the riots had subsided later in the year, the clergy were released. One of the bishops initially imprisoned by al-Rahman was called Eulogius, and during his imprisonment he read the bible to the other Christian prisoners to maintain morale. After their release, the persecution of Christians was renewed, causing many of them to leave and travel north to the Christian kingdoms of León, Navarra and Aragon.

For a while things remained quiet, but several months later there was a new wave of protests, and the emir turned to the Christian leaders as the ones most capable of controlling their own community. Instead of imprisoning them, he ordered them to convene a synod in Córdoba to review the matter and develop some strategy for dealing with the dissidents internally. He gave the bishops a choice: Christians could stop the public dissent or face harassment, loss of jobs, and economic hardship. He issued a decree by which the Christians were forbidden to seek martyrdom in fighting Islam. Unfortunately, the dissenters had drawn attention to themselves, and the Christian persecution escalated, as did Christian resentment and resistance. Finally, al-Rahman II ordered the first of a series of executions for sedition.

The old emir died in 852, but his son al Rahman III intensified the pressure on the Christians to conform. Tension escalated when the King of Asturias died and was replaced by his son, Ordoño, who, after he had put down a rebellion by the Basques, had to face an attack on his southern borders by al-Rhaman. Ordoño defeated the Moors, but in subsequent battles was beaten back. He offered support for the rebels in Toledo, which led to further defeats at the hands of the Moors. Finally, he encouraged the Christian settlement of the buffer zone, the “Tierra de Nadie,” which brought the Christian border closer to Toledo, the stronghold of the Muladi (Muslims of ethnic Iberian origin) and Mozarabs (Christians living in the Muslim controlled areas.)

To deal with this encroachment into his territory, al-Rahman dispatched troops under the command of his brother, el-Hakam. In the summer of 853, they met the rebel army near Andújar, but were led into an ambush and defeated. Initially the rebels were elated because they had captured many weapons and valuable baggage which el-Hakam’s troops dropped when they fled. Even though they had won a victory, the rebels knew that sooner or later they would face the full might of the emir’s army. Later that year, al-Rahman sent a stronger force, which met the combined forces of Asturia and the rebels of Toledo near the rio Guazalete. The battle was horrific even by the standards of the time. Twenty thousand rebels were killed, and in triumph, the soldiers of the emir cut off the heads of the fallen and piled them on the battlefield to deter others.

Meanwhile, in Córdoba, the unrest of the Christians was still causing problems for the emir. Forty eight people had been executed in Córdoba up to the year 857, most of whom were monks. Distrust of the Christians prompted the emir to remove all Christian officials from their palace appointments. Eulogius was still there and was working with the remaining Christians. It was during this period that he is believed to have been the first person to translate parts of the Quran into a language other than Arabic. He had been selected to be Archbishop of Toledo, but before he could take up his new post, events overtook him with disastrous consequences.

A young Muslim girl called Leocritia had converted to Christianity against the wishes of her parents. She came from a noble Muslim family and she begged Eulogius to hide her amongst his friends. For a while she was concealed in safety, but eventually she was discovered, and both Eulogius and Leocritia were arrested and sentenced to death. Eulogius was beheaded on March 11, 857 and Leocritia, four days later on March 15, 857. All 48 of the people that successive emirs had executed were canonised by the Catholic Church.

The execution of Eulogius. Photo: Biblioteca de Córdoba. The execution of Eulogius. Photo: Biblioteca de Córdoba.

Al-Rahman III now had to contend with betrayal from his own Arabic people. A powerful Muladi overlord formed an alliance with the Arista family of the Kingdom of Navarre and rebelled, proclaiming himself "The third King of Spain" (after al-Rahman III and Ordoño I of Asturias). A rebel Umayyad officer, Ibn Marwan, also rose up against the emir who, unable to quash the revolt, allowed him to found the free city of Badajoz, in what is now the Spanish region of Extremadura in 875.

The rule of the Arab emirs had brought many benefits, but to gain power they had trampled on the Berbers and the Visigoths. Al-Rahman III had encouraged and supported the arts and under his reign and those before him, the Caliphate of Córdoba had become a centre of learning. Córdoba overtook Constantinople as the largest, most prosperous city in Europe, and its fame spread throughout the medieval world. But while al-Rahman III was building the Shining City outside Córdoba, others were plotting his downfall. The man who would be greatest challenge to his rule was hiding in Morocco after narrowly escaping execution for murder.

3

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (8)

3

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (8)

Damascus robs the Berbers

Saturday, August 15, 2020

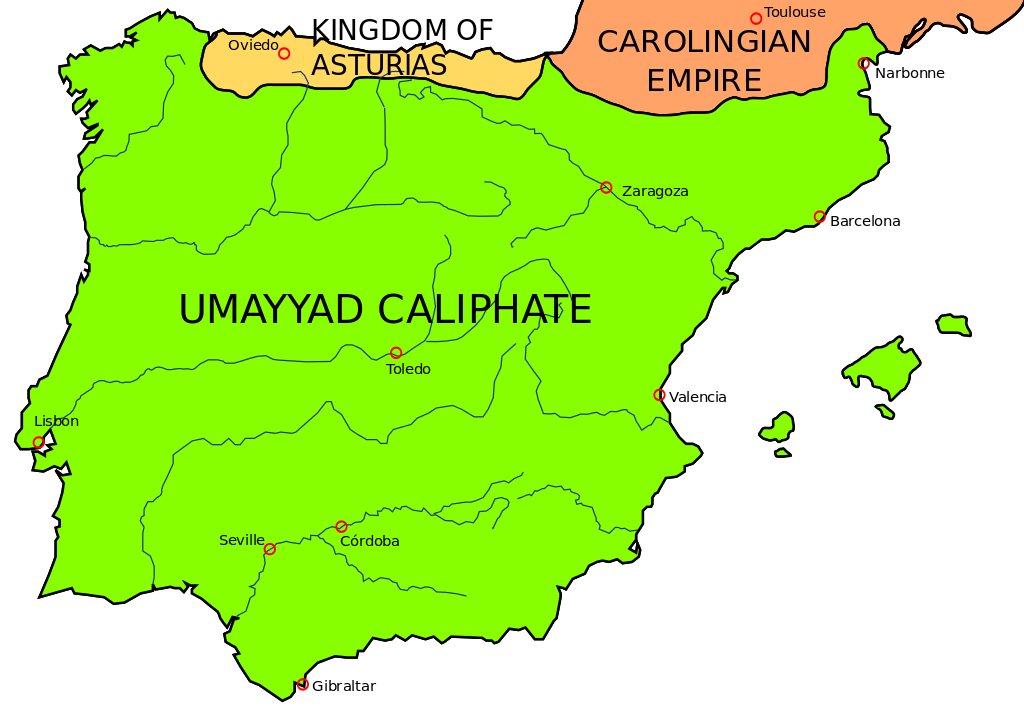

Last week’s post told of the invasion of Iberia by Musa bin Nusayr, the governor of the Arab province of Ifriqiya. At first, the newly conquered lands were administrated from Ifriqiya as a province of the Umayyad Empire, its governors appointed by the emir of Kairouan rather than the emir in Damascus. The conquerors renamed Iberia al-Andalus, and settlers began to flood in to occupy the relatively fertile land and establish a regional capitol in Córdoba.

Those Visigoth Dukes who recognised the authority of their new masters were allowed to keep their lands, creating areas around Murcia, Galicia and the Ebro valley where little changed. Those who could not live with the Muslims formed a refuge in the inaccessible Cantabrian highlands, where they re-grouped and defended their Kingdom of Asturias.

Having consolidated their gains in al-Andalus, the governors of the province sent Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi to make raids into the lands beyond the eastern Pyrenees, but he was driven back by Duke Odo the Great of Aquitaine. Undeterred, he crossed the mountains further west and attacked again, this time defeating the duke. He pushed further east into the old Roman province of Septimania, capturing Arles and Avignon and probing north following the river Rhone before he was stopped by a stronger Bergundian force led by Charles Martel at the Battle of Poitiers in 732. A coalition of Lombardians and Bergundian armies drove Al Ghafiqi back to the Pyrenees before finally expelling them from Gaul by 739.

The Mulsim invasion forces had been drawn from African Berbers with some Arabs of Ifriqiya and the Levant, but relations between the different cultures was strained in the years following the invasion. The Berbers had borne the brunt of the fighting to capture Iberia and vastly outnumbered the Arabs from the Levant, who now flooded in and took key posts in the administration, forcing the Berbers into a secondary, subservient role. Some of the new Arab governors began to mistreat their Berber counterparts, and before long, the Arabs had a Berber revolt on their hands. The Berbers had railed against their Arab overlords before in 729 and had even managed to carve out their own rebel state in Cerdanya, but the big revolt started in the Maghreb in 740.

To put down the uprising, the Umayyad Caliph, Hisham, sent a large Syrian army to Morocco. At the Battle of Bagdoura, the Syrians were soundly defeated by the Berbers. The news of their brothers’ success travelled to northern Iberia, where the mistreated Berbers also mutinied and deposed their Arab commanders. They formed a rebel army and marched against the Arab administrative centres of Toledo, Cordoba, and al-Jazeera. (Algeciras)

In response, the caliph in Damascus rallied his armies and sent 10,000 troops across the straits to help the governors of al-Andalus regain control. They crushed the uprising after a series of ferocious battles culminating in the Battle of Aqua Portora in August 742. However, the prejudice between the haughty Syrian commanders of the occupation, and the original Arab al-Andalus governors erupted in another uprising, which was put down in 743 by the Syrians led by the new governor of al-Andalus, Abū l-Khaṭṭār al-Husām.

Caliph Hisham’s army was drawn from far-flung parts of his caliphate and were organised into junds under their regional commanders, so al-Ḥusām assigned each of the junds a region to administer. The Egypt jund was split and given Tudmir (Murcia) in the east and Beja (Alentejo) in the west. The Jordan jund, Rayyu, (Málaga and Archidona). The Damascus jund was established in Elvira (Granada). The Filastin jund, Medina-Sidonia and Jerez. The Emesa (Hims) jund, Seville and Niebla and the Qinnasrin jund, Jaén. Instead of solving the problem of controlling of the new lands, it made things worse. The Regional commanders began a reign of autonomous feudal anarchy, severely destabilizing the authority of the governor of al-Andalus.

During this time of instability, the Berber garrisons holding the northern borders had deserted their posts to aid their brothers’ rebellion against the Syrians. The Christians in Asturias under their king, Alfonso I, swarmed out of the highlands and took control of the empty lands, quickly adding the provinces of Galicia and León to his kingdom. He evacuated the River Duero valley, bringing the people north within his kingdom and leaving a wide empty buffer zone between Asturias and the lands ruled by the Arabs.

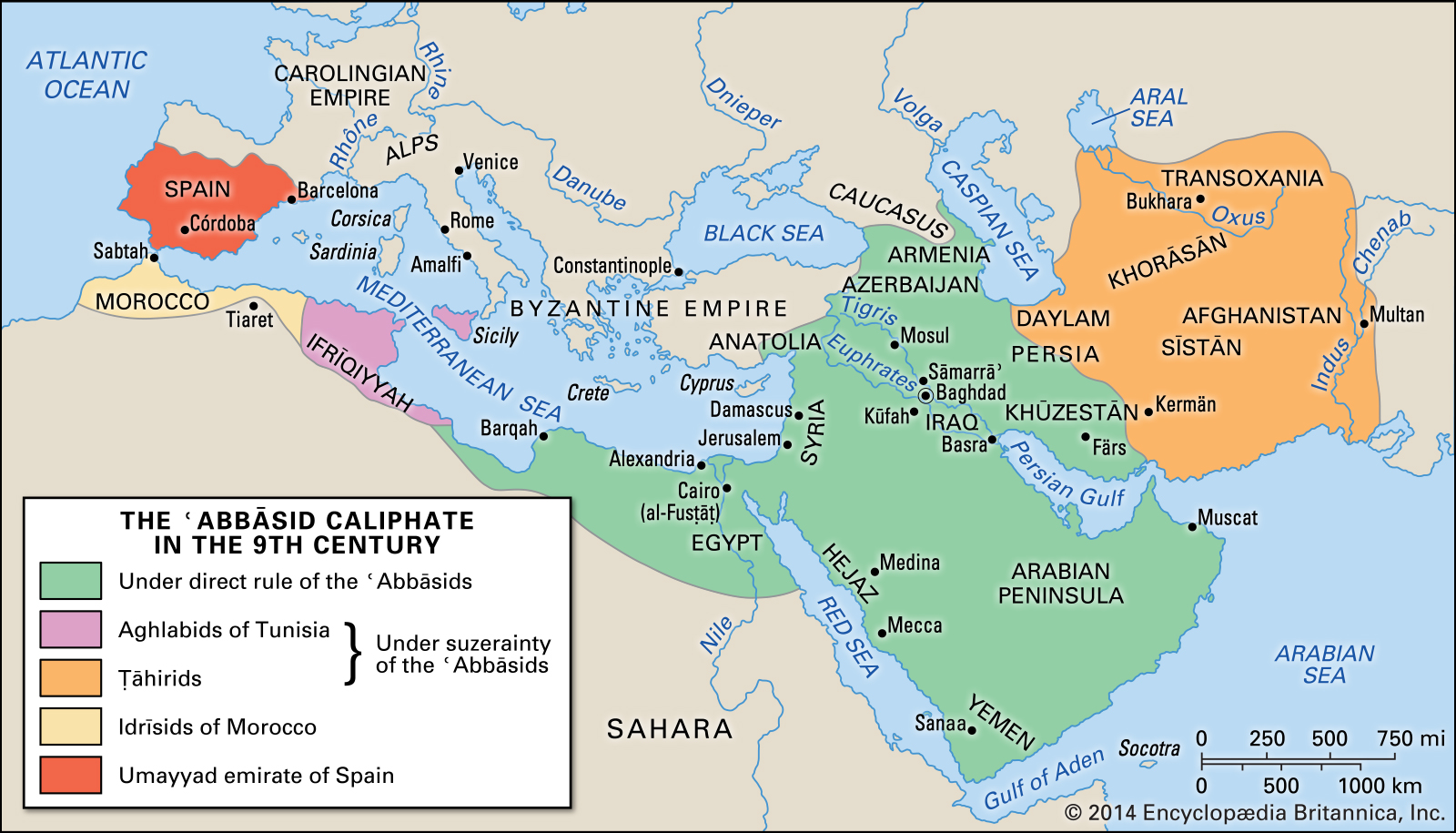

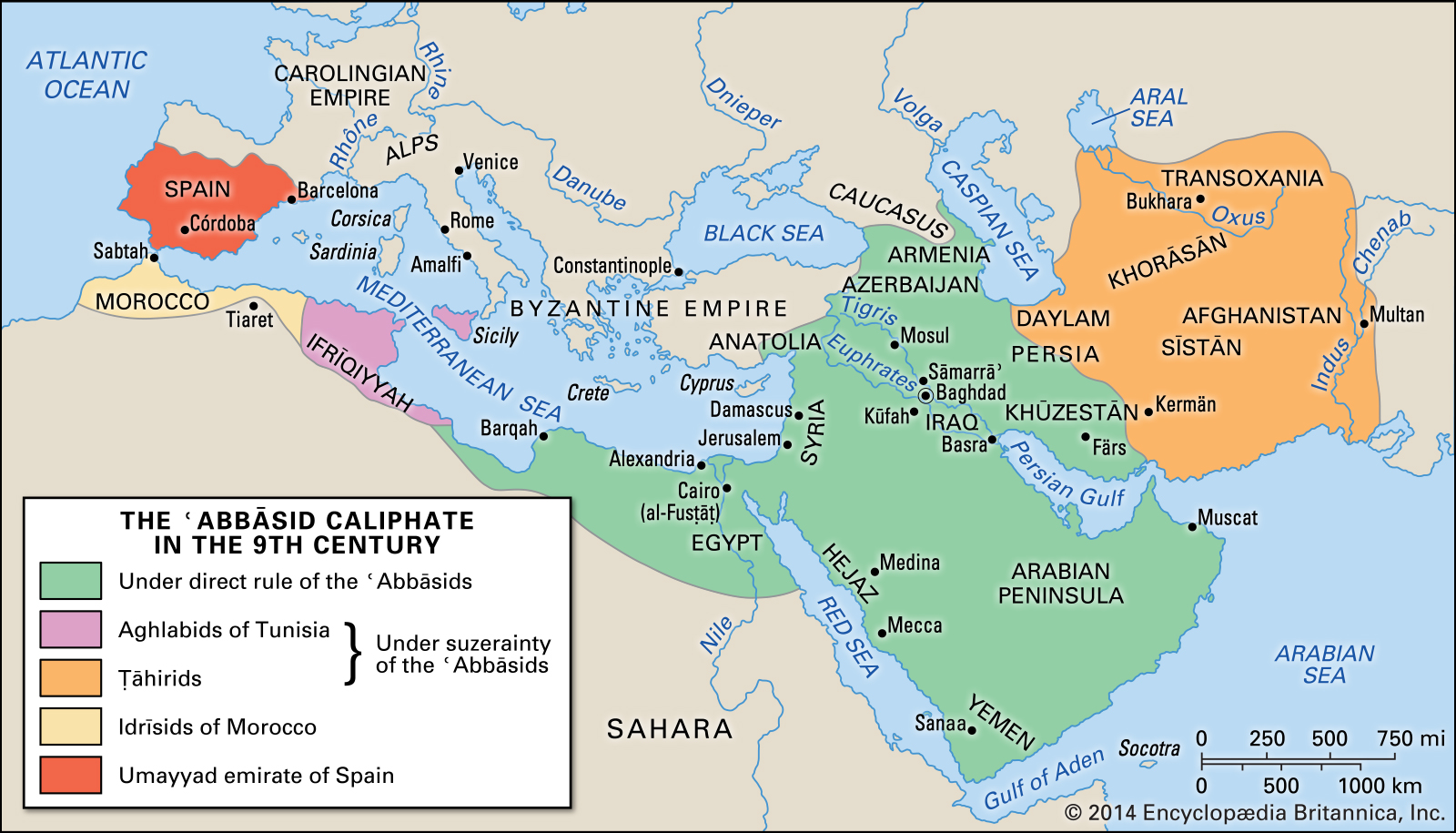

With al-Andalus practically out of control, the Caliph in Damascus found that he had other problems on his doorstep. The expanding Abbasid Caliphate was pressing on the eastern borders of the Umayyad Empire. The Abbasids were named after their founder, the uncle of the Prophet Muhammad Al-Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib. They eventually founded the city of Baghdad as their capital, and were a much more dangerous threat than the problems in Iberia. Caliph Hisham’s attention shifted eastwards, and Iberia was left to solve its own problems.

Map:Brittanica. Map:Brittanica.

When the Umayyad caliph lost interest in al-Andalus, the opportunistic Fihrid Arab family seized power in the western Maghreb under Abd al-Rahman ibn Habib al-Fihri, whilst his son Yūsuf al-Fihri, took control of al-Andalus. The demise of the Umayyad caliphate allowed the Fhirids to seek an alliance with the Abbasids against them, but they rejected the offer and demanded that they submit to their rule. The Fihrid family defiantly declared independence from all outside control.

The war went badly for Hisham, and the Abbasids controlled all the Muslim lands by 750 creating thousands of homeless Umayyad refugees. In a generous gesture, the Fihrids welcomed them and allowed them to settle in al-Andalus. These were the sons and grandsons of Caliphs, and had a more valid claim to al-Andalus than the Fihrid family. They aligned themselves with the disenchanted lords under Fihrid rule and rose up against them. In 756, led by the Umayyad prince Abd al-Rahman I, overthrew the Fihrid family and the prince established himself as Emir of Córdoba. He held the title for thirty years despite his rule being challenged by the al-Fihri family and the Abbasid Caliph. His descendants ruled from Córdoba for another century and a half, though not always in full control of the many competing factions. It was al-Rahman III in 912 who elevated the caliphate to its greatest level restoring by Umayyad control over all al-Andalus and North Africa. He proclaimed himself Caliph of al-Andalus in 929 and his power was equal to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad and the Fatimid caliph in Tunis.

This period is now known as the golden age of al-Andalus. Orange and lemon trees had been introduced, along with and the cultivation of olive groves and pomegranate trees. Grain crops flourished in the rich soil, making the lands around Córdoba the most advanced agricultural area in Europe. Irrigation and the use of the water-wheel turned al-Andalus into a fertile paradise which in turn generated a rich economy and supported a growing population. Rice, coffee, coriander and basil were introduced as crops, and the working of metal for cutlery and ornaments. The working of glass became common, and ceramic glazed tiles reached a zenith in design and production.

This impetus of sufficiency generated a scholar class, and Córdoba became renowned as learning and teaching centre which was equal the universities of Italy. The libraries of al-Andalus grew in the major cities, and the ones in Córdoba alone held ten thousand books. Astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, games and music were encouraged, and though Islam forbade alcohol, they invented sherry and perfected its production. One of the founding pillars of the Islamic faith was the development of the mind, and Córdoba became the Versailles of Iberia.

With a population of around five hundred thousand people, Córdoba overtook Constantinople as the largest, most prosperous city in Europe, and its fame spread throughout the medieval world. The transmission of ideas generated by al-Andalus during the al-Rahman caliphates were like water to the seeds from which grew the European-wide Renaissance.

It was during the reign of al-Rahman III that the beautiful estate of Medina Azahara, meaning The Shining City, was built. This was a tour de force of opulence and majesty in the early medieval world. With ceremonial reception halls, offices, gardens, workshops and baths supplied by aqueduct with clear water and a barracks for the palace guards. Azahara was a self-contained palace.

Photo: By Wwal Photo: By Wwal

The Shining City was extended during the reign of Abd ar-Rahman III's son Al-Hakam II between 961 and 976, but after his death it soon ceased to be the main residence of the Caliphs. In 1010 it was sacked in a civil war, and thereafter abandoned, with much masonry re-used elsewhere. It was a statement of power and wealth for the entire world to see and aimed at impressing his rivals in the Muslim world, the Ifriquian Fatmids and the Abbasids in Baghdad. The ruins were first excavated in 1910 and even now, only ten percent has been uncovered. There is a large cinema in the museum which gives the busloads of visitors a virtual reality tour of the city in its heyday.

Learning about the history of Spain is one of the themes of this blog and website, and one of the best ways to discover the past is to live there for a while. Medina Azahara is the setting for one of the 15 books of Joan Fallon. The shining City is set in this opulent epoch, and tells a story of love, family, and the choices that face ordinary people during difficult times.

1

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (13)

1

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (13)

The Islamic invasion

Saturday, August 8, 2020

When the Romans left Iberia, the Visigoth tribesmen once more had control over their own lands. Over two centuries, the fierce Visigoth tribesmen had become rich farmers then powerful noblemen, who owned huge swathes of land. Provinces were established and inevitable rivalries grew amongst their rulers. After a string of attempted coups, a duke named Roderick persuaded some of the other noble families and the Catholic Church to back his attempt to take control and unite all the provinces.

Duke Roderic Duke Roderic

In 710, he made his move by killing King Wittiza and taking control of the provinces of Lusitania and Carthaginensis. The king’s son, Achilla, held the rest of the country and mounted a counter attack. Many of the other provinces and their dukes remained neutral during the battles between the warring rival kings, and for a while control of Iberia swung between the two.

Visigoth Iberia Visigoth Iberia

Meanwhile, on the southern shores of the Mediterranean, greedy eyes were watching the events in Iberia. Musa bin Nusayr, the governor of the Arab province of Ifriqiya, comprising western Libya, Tunisia, and eastern Algeria had been receiving intelligence reports about the war between the Visigoth kings.

Musa was already a powerful leader amongst his own people. His parents had been slaves in Egypt, but had been given their freedom, and they returned to Syria where Musa was born. His father had risen to a position of power, and his patron Abd al-Malik, took a shine to Musa and guided his early career, making him co-governor of Iraq.

Around the year 700 the governor of Ifriqiya, Hasan ibn al-Nu’man, had been charged with expanding Arab control westward to take all of Morocco. Hasan was intolerant of the Berber Moroccans and had allowed his command to be weakened by constant attacks from the sea by Byzantine forces. In 698 he was relieved of his command and replaced by Musa, who showed respect to the Berber tribes. They returned his respect with their trust, and many converted to Islam voluntarily to join his forces. Using a mix of generosity, force and guile, he extended his master’s realm to include Tangier and all the Maghreb. He became the first governor of Ifriqiya who was not subservient to Egypt. Musa built a navy to defend his shoreline, which now extended from the Atlantic Ocean to the Nile, but at this moment, like a cat stalking a mouse, he was carefully watching events unfold just across the straights from Tangir.

It was not long before he saw his chance.

Julian, the Count of Ceuta, sent word to Musa asking for his help to fight the injustice caused to his people by Roderic. Julian claimed that his daughter had been raped by the evil king and promised rich pickings in Iberia if he would help him defeat him. Musa sent a small party of men under the leadership of Tariq ibn Ziyad to Tarifa to scout the land. They returned with booty, and the news that the south of Iberia was undefended.

In 712 Musa supplied Tariq an army of some 7,000 men, composed of both Arab and Berber soldiers. Tariq was a Berber soldier, who had converted to Islam, and with the help of Julian, who lent him the ships and guides he needed, he landed on the southern coast of Spain in mid-June of 712. He soon occupied the defenceless coast, but before moving inland he secured his supply port at the old Roman town of Iulia Traducta built at the mouth of a small river known as the river of honey.

Tariq did not know the name of the port, so he re-named it the outpost, or al-Jazeera in Arabic. Across the bay from al-Jazeera, the huge outcrop of rock that was visible for twenty miles in any direction was the first place that he landed, and his men soon named this massif Jabal al-Tariq … Tariq’s mountain. He consolidated his forces around al-Jazeera and then moved inland, guided by Julian’s men.

Roderick received news of Tariq’s invasion whilst he was fighting in the north of Iberia and quickly disengaged his forces to turn them south and defend his rear. On the way, he dispatched riders to ask the local dukes to provide fighting men and join him to repel the Moors. In his desperation, he sent a messenger to his arch enemy Achilla to send troops to help him. Achilla demanded a levy for his assistance, but eventually sent troops to join Roderick’s army.

Three weeks after landing, and several indecisive skirmishes, Roderick confronted Tariq with an army of 20,000 men between the coast and a town called Assidonia (Now Medina Sidonia.) Tariq had been supplied with battle hardened troops by his master Musa, but Roderick had been fighting with farmers who had been hastily summoned and poorly equipped. Some of his Dukes turned traitor and offered Tariq bribes if they would spare them in the coming battle. In the event, it seems that one wing of his army fled during the battle, allowing Tariq to come close enough to unhorse Roderick. With their king down, the battle turned to a rout, and Tariq pursued the Visigoth army to the banks of the River Guadalete where many were drowned. Roderick’s body was never found.

Musa, learning of Tariq’s success at the Battle of Guadalete, followed him leading another 18,000 troops. The Muslim invasion gathered pace as Tariq besieged Córdoba which soon fell and he promptly turned it over to the Jewish population who had suffered terribly under the yoke of centuries of Visigoth rule. They held the city while Tariq moved on to Toledo. Meanwhile, Musa besieged Hispalis, (Sevilla) which fell after three weeks and then moved on to Lucitania to take Mérida its capitol. Over the next few years, the two leaders conquered all the lands as far north as the Bay of Biscay and the south eastern regions of Baetica and Carthaginensis.

Musa died naturally while on the Hajj pilgrimage with Sulayman around the year 715/716. He had been disgraced, and the misfortunes of his sons had brought him into disrepute. Some medieval historians now attribute his deeds to another general, but the Moroccan peak Jebel Musa is named after him, and is perhaps his only recognition for the conquest of Iberia.

1

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (8)

1

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (8)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|