This really gets your goat

Friday, May 21, 2021

In the Naval Museum in, Barcelona is a full size replica of the El Real, flagship of the Christian Holy League, which fought the Ottoman Empire’s navy of the at the battle of Lepanto. The Holy League was a desperate coalition of the Republic of Genoa, the Republic of Venice, the Spanish Empire, Sicily, Sardinia and Malta, and was led by the Pope against the mightiest Muslim navy ever assembled. The original El Real had been built and launched in Barcelona, and it was one of the largest galeasses ever constructed.

The El Real: drawing: Alan Pearson. alanpearson.pixels.com

Philip II of Spain provided most of the funds for the campaign, as well as the El Real, but Venice provided half of the ships that fought in the battle. The crusades were over, and the Moors had been driven from Spain, but they had only crossed to North Africa, from where they continued the war at sea. All of Europe learned to fear the Barbary Corsairs as they became known.

In 1453 the Ottoman Empire captured Constantinople and firmly closed all the overland trade routes to the far-east. Over decades, they had been slowly choking the sea trade with repeated attacks on Christian trading ships. They controlled all the eastern end of the Mediterranean and ports along the north coast of Africa as far as the Atlantic, and their galleys prowled the vital seaways with impunity, capturing ships and enslaving their crews for oarsmen on their galleys. Genoa, Sardinia, Corsica, the Balearic Islands and even Rome itself were attacked

The Mediterranean, or the Sea of the Moors, as it was now being called, became the most hotly contested piece of water in the world. The Ottomans began to island hop in the Aegean, forcing Venetians to abandon their ports and flee. One of their most successful captains, Kheir el Din, (protector of the faith), but better known as Barbarossa, (Red Beard) was summoned by the Sultan of Constantinople and ordered to reorganise and enlarge the Turkish navy. The outcome was an immense fleet of over a hundred galleys and many more support ships. Venice was suffering from these repeated attacks and becoming alarmed with the growing strength of the Ottoman fleet. The Doge pleaded with the other nations around the Mediterranean to form the Holy League to confront the Moors once and for all.

Venice at that time owned one of the largest commercial navies in the world. It was made up of two distinct kinds of trading ships. The tall sailing ships which had large holds and were broad in the beam were the most numerous and popular. Venice had around three hundred of these. Of these three hundred, 30 could be considered superships weighing over 250 tons. These large vessels plied the routes to the eastern Mediterranean ports bringing Syrian cotton and Cretan wine.

The other kind of ship was the galley, or if it had a sail a galeass, which normally carried around 150 oarsmen. These oarsmen were not slaves and were armed, and so the galleys that carried precious cargoes were also well defended. Many also had a rams built into the prow, which could sink or severely disable another ship. Galleys were slower than the sailing ships and required huge crews serving as oarsmen, but they were much harder to rob. A direct descendant of Greek triremes, they were the elite of the Venetian navy, and often made quite long voyages through the Straits of Gibraltar and up the coast of Portugal, calling at Lisbon and Flanders in France before stopping in England to trade.

Over the centuries, it had been the Venetian shipyards that had built the best and biggest galleys, but by the late 1400’s they were struggling to find the timber that they needed to build ships. When traders first began using the Mediterranean as a super-highway, the forests around Venice began at the shore and climbed all the way to the Alps. They contained spruce, fir, larch and beech well as other timber which had more specialised uses aboard a ship. But the most important timbers for shipbuilding was the mighty oak, whose curved boughs made the ribs, and whose straight trunks were laid and joined for the keels. But by the time of Lepanto, the abundance of forests within the Republic of Venice had been depleted to critical levels for shipbuilding. The Venetians shipwrights toured the forests marking trees that were to be used for shipbuilding and imposed strict laws about felling trees. They provided armed guards for the woodlands, which effectively made them property of the state. It was at this crucial time when timber for new ships was scarce that the Turks reached the peak of their power.

Formation of the two fleets before the battle.

The two fleets met on 7 October 1571 in the Gulf of Patras and immediately decided to engage. The Christian fleet consisted of 206 galleys and six galleasses. Ali Pasha, the Ottoman admiral, supported by the corsairs Mehmed Sirocco of Alexandria commanded an Ottoman force of 222 war galleys, 56 galliots, and some smaller vessels. An advantage for the Christians was the numerical superiority in guns and cannon aboard their ships, as well as the superior quality of the Spanish infantry. It is estimated that the Christians had 1,815 guns, while the Turks had only 750 with insufficient ammunition. The Christians embarked with their much improved arquebusier and musketeer forces, while the Ottomans trusted in their greatly feared composite bowmen. Within the first hour, the flagship of the Turkish fleet had rammed the Real and boarded her. It was only the intervention of the League ship, the Colonna that saved the day. The crew of the Colonna drove off the Turks and captured the Ottoman flagship killing all the crew including their admiral, Ali Pasha. The banner of the Holy League was hoisted on the captured ship and the morale of the Turks plummeted. Isolated battles raged for hours more, but it was obvious that the Turks were defeated. By the end of the day, the Christians had taken 117 galleys along with 20 galliots and sunk or destroyed another 50 ships. Around 10,000 Turks were taken prisoner and 20,000 Christian slaves freed, and if we can believe the figures the, Christians lost 7,500 men, whilst the Turks lost 30,000.

When stock was taken after the battle it was soon realised that nothing decisive had been achieved. None of the territories captured by the Turks had been recaptured. If the Holy League (which was already falling apart) had pressed on they could have inflicted real damage to the Turks. In effect, all that had been achieved was to draw a line down the Mediterranean that said Christendom to the left, Ottoman Empire to the right.

Six months later, with the forests of Greece and Turkey at their disposal, the Ottomans had replaced more than 150 galleys, 8 galleasses, and in total 250 ships had been built, including eight of the largest capital ships ever seen in the Mediterranean. That same year (1572) the Turks took Cyprus. The Holy League was reformed to counter the new threat, but internal divisions made it ineffective and opportunities that could have been decisive were squandered. By 1573, Venice was forced to accept loser’s terms. Cyprus was ceded to the Ottoman Empire and Venice agreed to pay an indemnity of 300,000 ducats. The Republic of Venice was still very rich, and could afford to pay the high price for the foreign timber, but her traders would have to work very hard to counter the loss of her eastern trading empire to the Turks. Fortunately, Columbus’ discovery had literally opened up a whole New World of trade opportunities which was denied to the Turks. Venice and Genoa went on to even greater riches and glory, which is evident in its art and sculpture.

However, unnoticed until the need for shipbuilding timber became acute, the whole region had undergone one of the greatest ecological disasters since the stone-age. This was not about species extinction, but the proliferation of a single species encouraged by man. The unexpected villain of this story was the hardy little goat. Let me explain.

When the replica of El Real was built it required 50 beech trees for her oars, 300 pine and fir trees for her planks and spars, and over 300 mature oaks for the timbers of her hull. To build the ships of both fleets at the Battle of Lepanto required the felling of a quarter of a million mature trees. A forest that could provide trees of the size needed for shipbuilding could easily take 300 years to grow, and in the case of oak, a figure of 500 years is more reasonable. So, over the centuries of trading, why had the forests not grown back?

Around 9,000 BC, goats and sheep were first domesticated by early farmers somewhere around Syria or southeast Turkey. Both animals are highly socially hierarchical and will follow the biggest male, making it easy to imprint them with a human master. This was an immensely successful symbiosis and was quick to be adopted by early humans. Our ancestors were discovering grain crops at about the same time, meaning that settlements became villages and the first walled towns appeared. We know this because the abundance of animal bones at the sites where these early farmers lived suddenly changed from gazelle to goat. (Domestication of the dog precedes this by at least 5,000 years.) As the idea of farming grew, both animals followed their masters and populated the shores of the Mediterranean.

The goat had evolved in an arid climate and could live on plants that were usually inedible because of thorns or because they were high up on the tree. Goats will climb trees to get at the greenery, and they are voracious feeders. If goats remain in an arid climate then this ability is an asset, but if they are introduced to mixed woodlands their appetite soon becomes a problem. They will eat saplings, thus stopping new growth. Unchecked, they will strip a forest of its undergrowth up to a height of 3 meters. As old trees are cut or die, the forest is not able to regenerate. Topsoil is washed away, and the ecosystem that is left is one that can only support the goat. Once the goat is established, the land stands little chance of recovery and the forests recede. The goat herders can hardly be blamed for allowing the expansion of an animal that provides so much and requires so little. But after 2,000 years, the rich forests around the Mediterranean had all but disappeared. Only the maquis and garrigue which had grown in the rockiest and poorest soil could survive along with the goat, and they were a worthless replacement for the forests that provided timber for shipbuilding.

Of course shipbuilding did not stop, but the timber that the shipyards needed was to come from the Baltic, where the goat had never been introduced and the forests were pristine. Spain had also welcomed the goat, and large areas of Andalucia had been stripped of forest cover. But worse was to come when Philip II ordered the decimation of whatever forests were left to enlarge his navy in order to exploit the New World and eliminate his other maritime threat, the English Corsairs. His final solution for the “English ulcer” as he called them and their virgin queen would cost him dearly in timber, in lives, and the glory of Spain. But we can’t blame the goats for that.

3

Like

Published at 9:00 AM Comments (5)

3

Like

Published at 9:00 AM Comments (5)

Faith or fable

Friday, May 7, 2021

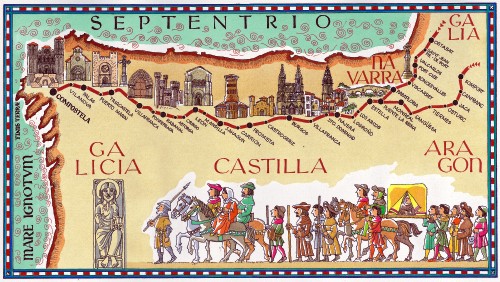

Following the crucifixion of Jesus, his disciple, James, (according to legend) made a pilgrimage to the Iberian Peninsula to spread the gospel, and when he returned to Judea he was beheaded by King Herod Agrippa I in the year 44AD. His death is detailed in the New Testament. What followed next is not so believable, though seemingly well documented.

Again, according to legend, his body, along with his followers, were brought to the Iberian Peninsula on a rudderless ship made of stone with no sail. Arriving on the northwest coast, they proceeded up the River Ulla to land at Iria Flavia, (modern-day Padron).

The Celtic Queen Lupia ruled these lands, and when asked by James’ followers if they could bury his body she refused and sent troops after them. The followers of James carried his body across a bridge, but when Lupia's troops tried to cross the bridge it collapsed killing her men.

Queen Lupia then and there decided to convert to Christianity and provided an ox and cart for the followers of James to transport the body. Unsure of where they should bury the sacred remains, his followers prayed and decided to let the ox continue until it chose a place to rest. After pausing at a stream, the ox finally came to rest under an oak tree at the top of a hill, and it is here that they buried the body of James.

James remained undisturbed for the next 760 years until 820 when a group of devotees at a hermitage called Peleo in the forest of Libradón saw miraculous lights in the sky which seemed to fall to earth over a hillock in nearby woods. When the abbot of the hermitage reported this to his bishop, Iria Flavia, the bishop told his superior, Teodomira, who came with an entourage of clerics to witness the events for himself. Over a number of nights, they all watched the stellar display. They cleared the forest over the hillock and began excavating and soon found a stone sepulchre containing three bodies. Teodomira immediately rushed away to tell King Alfonso II about the miracle that he had seen and the bodies that he had found.

Falling stars apart, the area of Santiago de Compostela was known to have been a Roman cemetery around 400, just before the empire began to collapse. It was also used as a cemetery by the Visigoth Suebi tribe when they replaced the Romans in the area, so finding a stone sepulchre there should not have been too surprising. Nevertheless, a new settlement and centre of pilgrimage emerged around the place of the discovery, which had become widely known by 865, and was simply called Compostela from the vulgar Latin for burial ground, compostia tella.

King Alfonso II, whose kingdom was surrounded by the Moors, realised the significance immediately. He needed an icon for his people to rally around, and the discovery of the burial place of St James fitted the bill exactly. The shrewd king ordered the clerics to build a chapel on the site, and legend has it that the king was the first pilgrim to visit the shrine. King Alfonso II had just begun a 23 year campaign against the Caliphate of Córdoba, and though Alfonso died in 842, his successor, Ramiros I, continued the reconquista. He won several battles against the Moors and claimed that it was the spirit of St. James that gave him victory.

This is where myth becomes entangled with the truth again. According to several sources, when Alfonso died, Emir Abd al-Rahman II reinstated an old jizya (a tribute) and demanded that the new king give him 100 virgins, which Ramiros refused to do. This resulted in the two armies supposedly meeting at Clavijo on 23 May 844 where the Christians were outnumbered, but fought valiantly.

St James at the battle of Clavijo, painted bu Giovanni Batistta Tiepolo.

Depending on which account you read, the year and date of the battle varies, and in truth, neither Christian nor Moorish records of the time contain any mention of the battle. The legend was first written down about 300 years after the supposed event, but the most important part of this fable was that at the peak of the battle, when defeat seemed imminent, some of the soldiers reported seeing a vision of St. James on a white horse brandishing a raised sword leading them to victory. The battle resulted in the death of 500 Moors and earned St James the title of Matamoros; but this invented story is still in the future.

The first church was built at Compostela in AD 829, and by 865 it had become widely known as the resting place of James. But it was the pilgrims who first started to arrive in steady numbers after 899 that changed the fortunes of Compostela. Its growing fame throughout Christendom brought floods of people eager to seek redemption for their sins by suffering the penance of walking all the way to the shrine. The route that they took became well known as the camino and well-worn by the feet of the faithful. To accommodate these religious tourists the camino sprouted hostelries, sanctuaries, shrines and a plethora of priests willing to give absolution – for a price. Compostela became rich on the donations of the fervent and their need for accomodation for the night. Along with its fame as a shrine, the political organisation of the area changed, and several kings of Galicia and León were crowned and anointed by the local bishop at the church, among them King Ordoño IV in 958.

This elevation in importance had not gone unnoticed, and the thought of devotees with money to spend spawned a series of copycat Compostelas; Saint Eulalia in Ovied, and Saint Aemilian in Castile began to compete with Compostela as rulers encouraged their own region-specific cults.

Compostela also attracted a more hostile kind of tourist. Towards the end of the tenth century, Viking raiders frequently attacked Galicia, which was recorded in Nordic sagas as Jackobsland or Gallizaland, and in 968 Bishop Sisenand II was killed by the Vikings whilst defending the town after he had begun the construction of a walled fortress around the sacred tomb and church.

These were lawless times, and the normal way for a king or caliph to increase his wealth or respect was to raid a neighbouring country to rob, pillage and take slaves. With its wealth and fame growing every year, Compostela became a target. In 997 the early church was reduced to ashes by Al-Mansur Ibn Abi Aamir, army commander of the caliph of Córdoba. The al-Andalus commander was accompanied on his raid by his vassal Christian lords, who received a share of the loot, but St James’ tomb and relics were left undisturbed. It was not a vendetta against Christians, but more a series of raids (fifty-seven in total) to enrich his rule and pay for the building of the Shining City near Córdoba. However, the religious significance of Compostela had raised it above all other shrines and construction of the present cathedral began in 1075 in the reign of Alfonso VI of Castile and the patronage of Bishop Diego Peláez. By this time, Compostela had become capital of the Kingdom of Galicia.

The Cathedral of Compostela The Cathedral of Compostela

The copycat Compostelas began to multiply and vie each other for recognition. St James’ whole body was allegedly found at Compostela, but the city of Doui in Northern France claimed that his head was there. So did Arras, Samur and Amiens. His hair, meanwhile, was on display at Troyes and Vezelay. Not to be outdone, and prepared to go all the way, Tolouse, Anger and Lorraine all claimed that they had the entire body of St James. But their claims were in vain, because the peregrinos walking along the camino were arriving in ever greater numbers.

The peregrinos were mostly single minded in that they wanted to reach Compostela. They were not interested in spending time (or money) in any of the towns on the camino, so the wily traders decided that a few miracles along the way might distract them.

One of the first miracles concerned a young German boy travelling with his parents along the camino when they stopped at Santo Domingo de la Calzada for the night. A waitress in the inn fancied the boy who ignored her, and for revenge, she hid a silver cup in his pack then claimed that he stole it. This crime carried the death penalty, and the boy was duly hung. His parents heard a voice saying that their son had been resurrected by Saint Dominic, and they went to the magistrate at Sanitago de Compostela to ask for his body. The magistrate was eating his dinner of roast chicken and rooster at the time, and told the couple that their son was as alive as the chicken that he was eating. The two birds on his plate immediately sprouted feathers, legs and heads and jumped of the plate crowing and clucking.

To this day, in memory of St. Dominic’s miracle, a rooster and chicken with white feathers are kept at the cathedral and are allegedly direct descendants of the original pair. A different rooster and chicken are exchanged each month, and when they are not at the cathedral, are kept in a chicken coop called the Gallinero de Santo Domingo de la Calzada, which the Cofradía de Santo Domingo (Confraternity of Santo Domingo) maintains with the help of donations. There is even a wayside shrine (hornacina) built in 1445 which holds a piece of wood from the gallows from which the boy was hanged.

A second miracle occurred at the church of O Cebreiro, when on one particularly cold and windy day, a parishioner from a nearby town came to take mass. The priest, not expecting anybody to turn up, berated the man for risking his health by coming so far on such a day for a little bread and wine. Instantly the bread held by the priest was transformed into the Body of Christ and the wine into his blood. Now called the Miracle of the Holy Grail, the story was spread throughout Europe in the Middle-Ages by the minstrels and the pilgrims of that time. The miraculous chalice and paten are preserved in the church of O Cebreiro, where the remains of both the priest and the peasant rest side by side. The miracle was reinforced in 1486 when Queen Isabel and King Ferdinand, who were in pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela donated a reliquary to keep and protect the Body and Blood of Christ. Nowadays, you can see the vitrines that preserve the chalice and the paten in the chapel of Santo Milagro de Santa María.

O Cebreiro O Cebreiro

In the middle of the 14th century the plague stopped the pilgrimages to Santiago; and also the supply of money. This was followed by the reformation, and the power of the Catholic Church began to wane in Europe. But eventually, the pilgrims returned. Very much later, a young Franco watched the arrival of the pilgrims at El Ferrol, his hometown, to walk the 70km. to Compostela. He was not religious, but he realised the enormous power wielded by the church. During the civil war, he tried to control it by choosing his own bishops, but the Vatican overruled him. Not to be outdone, he imprisoned unruly priests in a special priest-only prison in Zamora. During the latter part of his tyranny, Franco tried to unite his country by promoting St. James as Spain’s Patron saint, and for the filming the of El Cid in 1961, he lent several thousand of his soldiers as extras, but the power of St James had waned.

With the death of Franco, and the opening up of Spain, the peregrenos flooded back to the camino in ever greater numbers, giving the north of Spain a much needed economic boost. Covid 19 stopped the influx of tourists for a year, but once again the route is open to people who perhaps want to give thanks for surviving the epidemic.

3

Like

Published at 9:31 AM Comments (4)

3

Like

Published at 9:31 AM Comments (4)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|