The cornered Caliphate

Saturday, December 19, 2020

The battles of Pinus Puente and Teba were a huge psychological setback for the Caliphate of Granada. The age of splendour was gone forever, and it was now very clear that the Christians were intent on driving the Moors out of Iberia for good; it was just a matter of time.

The Marinids in Morocco had lost all their lands in Iberia, and their port of Algeciras, which had been occupied by Berbers for 628 years had been sold to the Granadans. Gibraltar, just across the bay, was occupied by the Christians, as was Tarifa. They also controlled much of the land around the two ports. It was obvious that taking isolated Algeciras was the next item on the Christian’s agenda.

Just as so many times in the past, the Granadans turned to Morocco in their time of need. Muhammed IV, Emir of Granada, asked the Marinid emir Abu al-Hasan 'Ali to help him take back Gibraltar and perhaps claw back some of the land that he had lost to the infidels.

In late 1332 Abu al-Hasan ordered his navy to secure the bay of Algeciras and the waters around Gibraltar. The following spring, he sent an invasion force of 5,000 troops who laid siege to Gibraltar. Within two months, the town had surrendered, and the Granadans helped the Berber troops to expel the Christians from the surrounding area, so that the two ports were once again within the Caliphate of Granada. This made it feasible to plan bigger campaigns against the Christians. However, in the ever changing political climate of the Caliphate of Granada, the reigning emir, Muhammad IV was assassinated in 1333, and his 15 year-old brother, Yusuf, became emir under the regency of his grandmother, Fatima. She and her ministers negotiated a four-year peace treaty with Castile, Aragon and the Marinids. In the brief breathing space that the treaty supplied, the family of the dead emir expelled the Banu Abi al-Ula family, the killers of the old emir and their hired Marinid mercenaries, the Volunteers of the Faith. When the dust had settled in the caliphate, the young emir and his advisors agreed closer ties and alliances with the Marinids, knowing that the next onslaught from the Christians could be fatal for Granada.

Abu Hasan slowly gathered his forces, notably his navy, to stage an invasion on a scale not seen since the Marinid raids of 60 years earlier. By the end of 1340, he had assembled a fleet in the harbour at Ceuta. Sixty galleys, along with 250 other kinds of boat were tied up or anchored in readiness for the invasion. They landed troops at Gibraltar, but the admiral of the Castilian navy, Alfonso Jofre de Tenorio, who had surrendered Gibraltar in 1333, challenged the Marinid fleet commanded by Muhammad ibn Ali al-Azafi. The resulting naval battle on 8 April resulted in the encirclement and capture of 28 of the Castilian galleys and the death of its admiral. The Castilian navy was scattered, and only 16 of its galleys reached friendly ports. With control of the straits established, Abu Hasan began ferrying troops and supplies to Iberia, and by late September, with the aid of the Granadan emir, had encircled Tarifa. Believing, that the Castilian fleet’s losses would take the best part of two years to make up, the Moroccan emir stood down many of the front-line ships that he had used and returned those which he had borrowed for the invasion. He left only 12 ships to guard the bay of Gibraltar.

During the build-up to the invasion, King Alfonso XI had begun increasing the size of his fleet by ordering the building of 27 new ships in the dockyards of Seville. The half-ready ships were hastily completed and sent downriver. These joined the Portuguese ships loaned by King Afonso, and with the addition of 15 hired Genoese galleys, he had enough ships by October to close the straits to the Moroccans. Abu Hasan and Granada lost their supply of food and replacement troops for any further incursions into Christendom. On 10 October, the Moroccan emir made a desperate concerted attack on Rate Castle at Tarifa, which was repulsed with great loss of life on both sides. On the same day, an Atlantic storm wrecked 12 of the Castilian galleys and drove them ashore. The naval battle for the straits was becoming expensive in ships and lives.

On land, King Alfonso left Seville at the head of a column of troops intent on relieving the siege of Tarifa. On 15 October the King of Portugal joined them, and they stopped at the Rio Guadalete to wait for further Castilian and Portuguese forces to join them. Ten days later, the combined army, now 20,000-strong, crossed the frontier into the Caliphate. As soon as he received news of the approaching Christians, Abu Hasan abandoned the siege and re-grouped his forces on a hill outside Tarifa on the shoreline, whilst the Granadan emir, Yusuf I, took up position on an adjacent hill. The Christians arrived on 29 October and faced the Moors across a half-kilometre wide valley crossed by two streams, El Salado and La Jara.

During the first night after their arrival, King Alfonso ordered 4,000 foot-soldiers and 1,000 cavalry to march through the night, bypass the camps of the Moors, and reinforce the garrison at Tarifa. They were sighted by a 3,000 strong detachment of Moorish light cavalry, who for some reason offered only slight resistance. More significantly for the coming battle, the commander of the cavalry told Abu Hasan that no Christians had reached Tarifa.

In a dawn meeting with his lords and advisors, King Alfonso decided that he would lead the army of Castile and attack the forces of Abu Hasan, whilst the Portuguese, reinforced by 3,000 Castilians of the orders of Alcántara and Calatrava, would engage Yusuf I. Two thousand inexperienced troops were left to guard the Christian camp. The Castilian vanguard, led by two brothers from the Lara family successfully crossed the Jara, but met stiff opposition from the Moors at the El Salado. The king’s two sons, Fernando and Fadrique, led a group of 800 knights to a small bridge and drove through the defending Moors to take it. Their father then reinforced them with 1,500 more knights, and the Christians surged across the gulley.

.jpg) The battle of Rio Salado. The battle of Rio Salado.

In the centre ground, Juan Núñez de Lara broke the enemy line, crossed the stream and began climbing the slope to where Abu Hassan had set up his command centre. At this point, the reinforced garrison of Tarifa appeared at the rear of the Marinid lines and drove in a wedge of troops that split Abu’s forces in two. Half fled to Algeciras and the other half joined the main body of Moors in the valley below. With half his forces pursuing the retreating Moors or looting Abu’s camp, King Alfonso found himself in the thick of the main battle and dangerously exposed. Abu Hasan called his troops to rally and attack the centre, and King Alfonso drew his own sword and was about to fight hand-to-hand with the surging Moors when the Archbishop of Toledo, Gil Álvarez Carrillo de Albornoz, grabbed the reins of his horse and stopped him. Luckily, Castilian troops surrounded the king and pushed the Moors back. When the troops who had been looting Abu’s camp realised that their king was in danger they returned to the battle and attacked the Moors from behind. Finding that they were now surrounded, Abu Hassan’s forces broke and fled to Algeciras. Only the Granadans were still in position, but when the Portuguese, reinforced by the Castilians, fought their way across the Saldo and attacked them they also fled. From first contact to the final rout had taken just three hours.

The Christian pursuit of the Moors was relentless and little mercy was shown. Abu’s camp was destroyed and looted and many of his wives were killed along with the nobles who had fought with the emir. Both emirs escaped and took refuge in Gibraltar, Abu crossed the straits in a galley that same night and Yusuf returned to Granada.

This was the last Marinid invasion of Iberia, and in1344 the Christians took the fortress of Algeciras after a siege that lasted 2 years. When the city fell, Alfonso XI signed a peace treaty with Yusuf, but constantly broke it by attacking the borders of the Caliphate. He only captured a handful of isolated castles on the border, but he did make a determined effort to take Gibraltar, again in violation of the treaty he had signed. The siege held for a year before the Black Death swept through Iberia and King Alfonso died from the plague. Yusuf granted free passage to the Christian troops as they withdrew carrying the body of their king.

Even though his reign was marred by constant Christian attacks and internal insurrection Ysuf I was responsible for encouraging literature, architecture, medicine, and the law, and he oversaw the construction of the Madrasa Yusufiyya inside the city of Granada, as well as the Tower of Justice and various additions to the Comares Palace of the Alhambra. Many great cultural figures served in his court, and historians consider this to be the golden era of the Caliphate of Granada. Ysuf I was assassinated by a madman while praying in the Great Mosque of Granada, on the day of Eid al-Fitr, 19 October 1354.

Castile also suffered its own royal convulsions until Queen Isabel of Castile and Prince Ferdinand of Aragon stabilised a newly united España when they married at the Palacio de los Vivero in Valladolid on the 19 October 1469. They inherited a bankrupt country, but just to the south of the united Christian kingdoms lay the rich farmlands of the Islamic Caliphate of Granada, and they began a new campaign against the Moors. Muhammad XII of al-Andaluz was his full title, but Emir Boabdil as, he was known in the palace, gathered his troops once more to fight in what had been for him a ten-year war of attrition. It was not really his war; the war against the Moors had begun centuries before. Boabdil was just unlucky to have to bear the shame of surrendering the last of the Muslim lands to the Christians. In 1492, the last Emir of Granada handed Queen Isabel the keys to the city, and the whole of España, including Sardinia, Sicily and the Balearic islands came under Christian rule.

The surrender of Granada The surrender of Granada

Accompanying the King and Queen when they entered Granada was a man who had been courting favour with them, and had been invited to share in their triumph. Christopher Columbus had sought the finance from all the kingdoms for a voyage across the Atlantic, where he was convinced he would find the Asian continent and lucrative trade. Isabel was dubious, but Ferdinand persuaded her to give him the money and ships that he needed.

Just ten weeks after the fall of Granada, Isabel issued the Alhambra decree. It seems to have been all Isabel’s idea, and the theory is that her confessor had changed from the tolerant Hernado de Talavara, to the fanatical Francisco Jiménez de Cisternos. España was about to enter its most awful era; the Inquisition and the Conqistadoras of America.

We have come full circle. This is where I started earlier in the year at the beginning of lockdown. I have thoroughly enjoyed writing these blogs, and I hope that you have enjoyed reading them. I know that my blog and website has been shamelessly copied and reproduced elswhere, but they say that imitation is a form of flattery. Remember that you saw it here first. I would like to thank my 27,000 visitors for supporting me, but I am stopping for Christmas now.

I would like to wish you all a Merry Christmas and let’s all hope for a better New Year in 2021.

2

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (11)

2

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (11)

The story of Black Douglas

Saturday, December 12, 2020

After the death of his mother in 1321, Alfonso XI had to wait four years until he was old enough to be crowned. The people who were running his kingdom as regents were unscrupulous and greedy, but he could do nothing about it. As soon as he was crowned, he declared war on the Caliphate of Granada. The death of his uncles and the hawks in the Cortez ensured that he continued the war against the Moors. In 1325 he sent out invitations for other kingdoms to join the campaign and share the booty, but in the meantime he initiated hostilities by marching his troops to the nearest and least guarded part of the frontier just 50 miles from Seville.

His objectives were Wubira (Olvera), Ayamonte, Pruna, Torre-Alháquime and Teba. The first four were outposts, but Teba guarded the road down to Málaga, a vital trade route within the caliphate. He chose reliable and trusted friends to help him, one of whom was the son of Alonso Pérez de Guzmán, Juan Alonso, the new Duke of Sanlúcar de Barrameda. In1327 he arrived at Ayamonte and surrounded the small fortress, then pressed on to Torre-Alháquime and Wubira, which he laid siege to. The garrison at Ayamonte slipped away in the night to Ronda, and Riu Gonzalez de Manzanedo, the Sevillian nobleman in charge of the siege there gave chase. He did not go far before he met the far superior forces around Ronda, and was lucky to escape with his life.

The fortress of Olvera. Photo; Wikipedia. The fortress of Olvera. Photo; Wikipedia.

The sieges of Wubira and Torre-Alháquime were successful, and the Christians entered the towns and took control. The Moors were given the choice of staying, or moving into the caliphate, which still controlled nearby Ronda and Ardales. Pruna held out, and was not overcome until much later. Content with his first campaign, the king left a garrison headed by Rui Gonzales and ceded the newly occupied lands to Juan Pérez de Guzmán. He then left Olvera and returned to Seville, where he began another round of fundraising for the next assault on Teba.

It took two years to organise the next attack on the caliphate. The coffers of his kingdom were nearly empty after the 1327 campaign, and he offered a share of the plunder to the King of Portugal if he supplied troops for the attack on Teba. The offer was agreed, and he provided 500 knights, but for a limited period. All Christendom was watching the war against the Moors in Iberia, and religious fervour had been whipped up by the church. During his stay in Seville, King Alfonso had sent out offers to mercenary warriors throughout all the kingdoms, and knights from all Europe responded. They gathered in Córdoba during the winter of 1329 and King Alfonso led the Portuguese troops and other contingents who had arrived in Seville by boat. Among these mostly foreign soldiers were a group of Scottish mercenaries. They came with a letter of recommendation from their king, Edward III of England.

The Scottish troops were nothing like the other troops that had been arriving all winter. For a start, when not in armour, they wore brightly coloured skirts, and even though there were many English-speaking mercenaries marching with Alfonso’s column, few could understand their speech. Other English mercenaries who had fought against them in England’s wars spoke highly of their fighting abilities, and 19 year-old Alfonso was enthralled by them.

He offered them the same terms as the other mercenaries, but they refused all payment. Their leader, Sir James Douglas, who had earned the name Black Douglas during the battle of Bannockburn, explained their mission to the king. The year before, the King of the Scots, Robert Bruce, lay dying and asked his friend Sir James to embalm his heart when he died and take it to the Holy Land on a crusade. (According to one chronicler) Bruce had always wanted to make the trip, as many had done before. Sir James wore the embalmed heart of his dead king around his neck in a small casket, and when he heard of the coming battle against the Moors, he decided that this was near enough to a crusade and joined the other mercenaries. Sir James declared that he and his men were prepared to offer their arms in the service of the king free as humble pilgrims seeking absolution for their sins. Alfonso assigned them experienced guides to train them in the fighting techniques of the Moors and gave them command of all the foreign mercenaries that he had hired.

The Scottish poet, John Barbour recorded the names of the Scottish knights accompanying Sir James as: Sir William de Keith, Sir William de St. Clair of Rosslyn, the brothers Sir Robert Logan of Restalrig and Sir Walter Logan. Other chroniclers have mentioned that at some point, this group was accompanied by John de St. Clair, younger brother of Sir William, Sir Simon Lockhart of Lee, Sir Kenneth Moir, William Borthwick, Sir Alan Cathcart and Sir Robert de Glen.

In June 1330 they crossed the frontier and made camp near to Almargen, five miles west of Teba. King Alfonso had to wait for his siege towers and catapults before he encircled the castle, and he immediately realised that he had a problem with water for his animals and troops. The castle was on the top of a substantial hill, and the nearest water was around the other side of the hill in a valley. Each day, the animals had to be led around the hill to the River Turón to be watered.

The Castle of the Stars at Teba Photo; Inland Andalucia. The Castle of the Stars at Teba Photo; Inland Andalucia.

The same General Uthman ibn Abi al-Ula who led the cavalry at the battle of Pinus Puente was commanding the emir’s forces around Málaga, and the Berber nobleman led six-thousand cavalry and several thousand foot-soldiers north to defend the castle at Teba. Uthman's force crossed over into the valley of the River Turón, where they pitched camp between Ardales castle and the supporting fortress of Turón, ten miles south of Teba.

Uthman took advantage of the need to water the animals and attacked the watering parties, knowing that without water Alfonso’s army would have to retreat. This happened several times and Alfonso knew that it was a lure to a trap. Uthman had hidden his main force in a valley, where they waited to surprise Alfonso’s troops. The King prepared his own trap and sent a large force of troops to accompany the watering party. He also ordered a reserve force to be ready to mount a counter attack.

Before the siege engines arrived, and on the eve of engaging Uthman’s troops, the Portuguese announced that their allotted time of service was up and they were going home. King Alfonso was furious, but could do nothing. At dawn the next day, a battle developed at the river. When the king was notified that his men had been ambushed, he ordered the second force, led by Don Pedro Fernández de Castro, with the Scottish knights in the vanguard, to assist the first. Uthman’s plan was to engage the watering party and then attack the unsuspecting Christian’s main camp with his cavalry. But when his jinetes crested the hill, they found row upon row of armed soldiers led by Douglas and ready to fight. The Moors retreated, and the Christians advanced.

Down by the river, things had not gone well for Uthman, and when the Scots arrived they found the Moors in full retreat. They charged, and fell into a classic Moorish cavalry trap. The knights separated themselves from their foot-soldiers, who were busy looting, and chased the cavalry, who wheeled around and surrounded them. One-by-one, they were unhorsed and cut down. Douglas was trying to reach Sinclair when he was surrounded. When the battle was over, almost all the Scots were dead. King Alfonso ordered Rodrigo Álvarez de las Asturias to attack with a further 2,000 men, and the Granadan retreat turned into a rout. Despite further skirmishes, Uthman made no further attempt to raise the siege, and shortly afterwards the garrison of Teba surrendered. The old Berber general died some weeks later.

The poet Barbour relates that the body of Douglas and the casket containing the heart of his king were recovered after the battle. The bodies of the knights were boiled until the flesh fell from them and their bones were brought back to Scotland. Douglas’ bones were buried at Dunfermline Abbey.

The plaque commemorating the Battle of Teba The plaque commemorating the Battle of Teba

The Battle of Teba was not decisive, and the lands around the castle were in dispute for the next 150 years. This round of victories for the Christians prompted the Marinid emir, Abu Hasan, to send forces in support of Muhammad IV to take Gibraltar in 1333, but the Marinid emir’s attempt to take back Tarifa in 1340 led to a disastrous defeat at Rio Salado, which would end the intervention by Marinid caliphs in the affairs of Iberia, leaving the Caliphate of Granada alone and isolated in a country ruled by Christians.

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (7)

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (7)

A Traitor's Demise

Saturday, December 5, 2020

After nurturing her son Ferdinand until he was old enough to be crowned, it must have been a numbing loss for Maria de Molina when he died in 1312, aged 26. To prevent further bloodshed between the competing factions, she stood in again as regent of Castile for her one year-old grandson, Alfonso. It would be another 12 years until he was old enough to be crowned. Whilst the child grew to age, Maria had to allow her lifelong enemy, John of Tarifa, to become his guardian and mentor along with one of his uncles, Pedro.

The spectre of further invasions from Africa by the Marinids was still troubling the minds of many in Castile, and the pope was eager to remove Islam from Iberia altogether. In Fez, Abu Sa'id Uthman, the emir of the Marinids, was a pious and peace-loving man who was facing rebellion from his own son. In 1313, to rid himself of any further military entanglements in Iberia, Abu Sa'id returned the towns of Algeciras and Ronda to the Naṣrid ruler, Ismail I of Granada. The knowledge that the Marinids were unwilling or unable to help the Granadans inflamed the hawks and glory seekers in the kingdoms. During a meeting of the Cortez of Medina del Campo in 1318, it was decided that Pedro and Juan would lead the allied nobles to initiate another invasion with the intention of striking at the heart of the caliphate.

During the winter of 1318 supplies for the invasion were stockpiled in Córdoba and plans were drawn to have the armies assemble there in the month of June 1319. Caliph Ismail I of Granada sent an urgent appeal to the Marinid emir for assistance, but Abu Sa'id Uthman imposed such onerous conditions that the Granadans decided to face the Christians without him and began amassing their own troops on the border.

Long before the fateful meeting of Cortez of Medina del Campo, Castile had signed a non-aggression treaty with Ismail I, and the emir wrote Pedro a letter reminding him of its terms. Pedro was caught between the Cortes and his conscience, and requested that the kingdoms respect the treaty. Pope John XXII heard of his lack of commitment and threatened to excommunicate Pedro unless he led the army. Furthermore, he elevated the attack to that of Holy Crusade and offered him a portion of the tithes that the church collected on the proviso that he did not sign any further peace treaties with the emir, “Under pain of obedience and love of the Holy Eglesia.”

As with the siege of Algeciras, King Jamie II of Aragon was asked to attack on a second front in the east, not to capture territory, but to devastate the lands of the caliphate and then withdraw. The pope gave Jamie the same offer of church tithes, but Jamie refused to join the attack. When the emir heard of the threats made against Pedro he wrote another letter expressing his “Very great regret” and that he would have liked to live in peace in his own lands, but would leave the outcome to the judgement of God. Many of the Castilians were unhappy with breaking the treaty with the emir, and criticism of the attack grew in Christian lands. Nevertheless, the invasion plans went ahead unchecked.

Pedro went to Toledo to meet the troops of the Order of Santiago, Calatrava and the Archbishop of Toledo, Gutierre Gómez de Toledo. He ordered them to bring their army to readiness and to march them to the border. Next, he travelled to the city of Trujillo in Extremadura and met with the Masters of the Order of Santiago to whom he gave 3,000 doubles of gold so that the Crown could recover the castle of Trujillo, which had previously been pawned to raise money. Seville was where the siege catapults were stored, and Pedro ordered them to be transported to the border. His final meeting was with the heads of all the orders and the Archbishops of Toledo and Seville at Jienense de Ubeda, where he told them that their first objective was the Castle of Tiscar. John, who was feeling unwell, decided to stay in Córdoba.

Tiscar was chosen because, according to Pedro, it was “the strongest fortress the Moors had,” but just a few days the after the siege began, the castle surrendered. Its commander, Mahomad Handon, abandoned it and its 4,500 inhabitants left for nearby Baza, their safety guaranteed by Pedro. Tiscar was an outpost to the east of Jaen, and in the greater picture of events was a minor success. The rapid fall of Tiscar would suggest that the emir sacrificed the citadel to give Perdro something to offer the pope. He could always take it back later. However, John was now worried that Pedro was stealing the glory for the campaign with such a rapid success, so he left Córdoba and sent word for them to meet at Alcaudete.

Alcaudete was on the border between the caliphate and Christendom, and John left some of his troops under the command of his son to cover their rear at Baena. He persuaded Pedro to focus their campaign on the Vega de Granada, where the looting would be more profitable, and who knows, they may even capture Granada, the greatest prize of all. The two united armies numbered around nine thousand horsemen and several thousand foot-soldiers. John decided to take the lead, and Pedro was to stay in the rear with the Master of the Orders of Santiago, Calatrava, and Alcántara, the Archbishops of Toledo and Seville, and by numerous members of the high nobility.

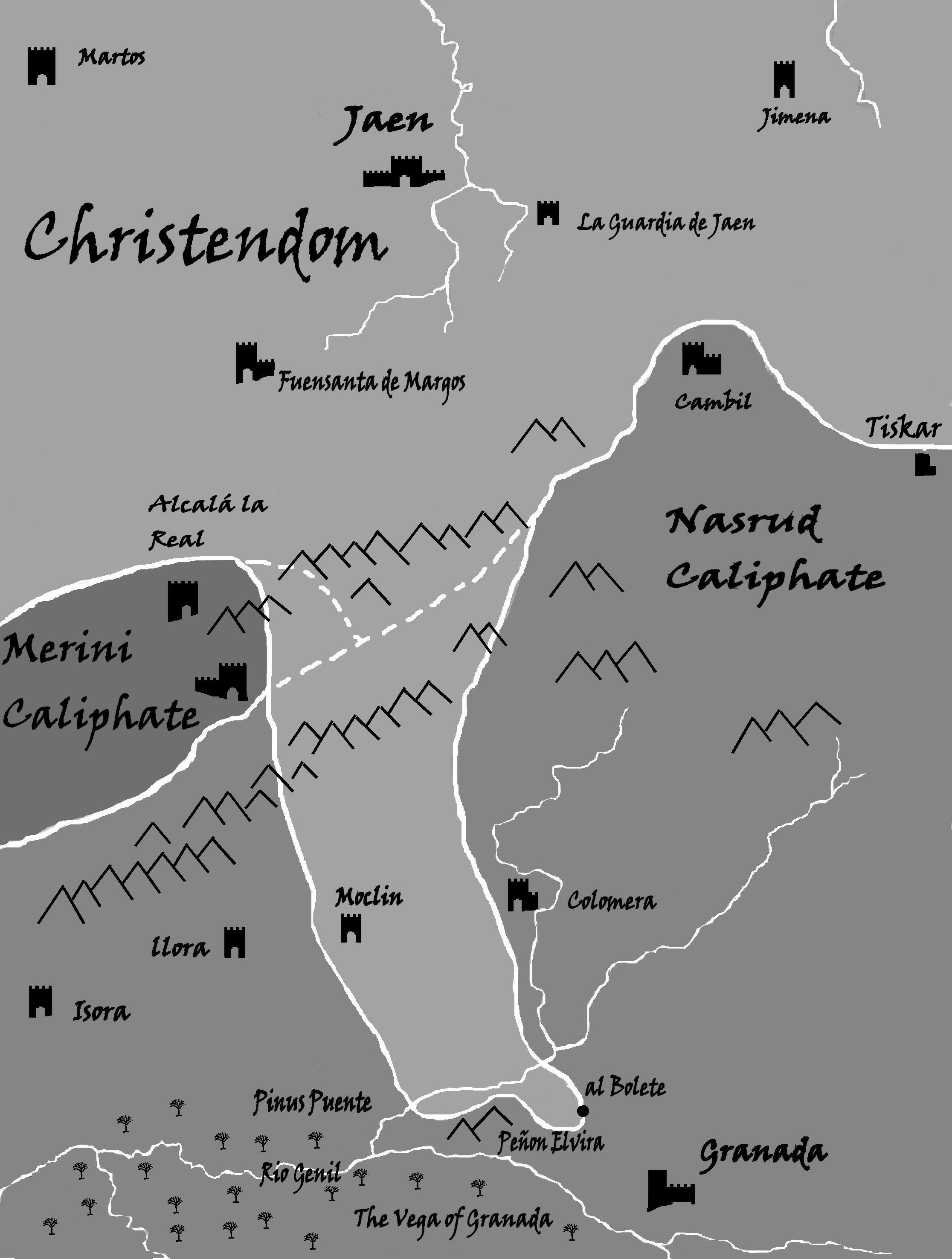

John drove his troops through to Alcalá la Real, where they camped overnight and the following day looted the surrounding countryside. They moved on to Moclin and Illora and rather than waste time trying to besiege the fortresses there, they bypassed them and marched on to Pinus Puente near to the confluence of three small rivers before they joined the Rio Genil. They were now nearly at the gates of Granada, and they had employed the same slash and burn tactics as used by the Marinid invasions. Juan’s troops had accumulated huge amounts of booty, but were tired and decided to camp by the rivers and rest.

A row broke out between John and Pedro when John suggested withdrawing to Christendom with their booty. Pedro was indignant that they had fought their way to Granada and were going to waste the opportunity to capture the city. John was right; they had over-extended their lines deep into the caliphate and were in danger of being cut off and surrounded. The emir could draw upon huge reserves of men, and the longer they remained, the more dangerous it would become. Relations between the John and Pedro had become so strained that they were barely talking to each other. The Christians were now in a very perilous situation. John’s plan prevailed, and the Christians began to retreat. Pedro was put in the lead of the withdrawal and John was to be the rear-guard.

General Ozmin was commander of the Granadan defence and had prepared the city for a siege. When he realised that the Christians were retreating he swiftly changed from defence to attack. He led a force of five thousand cavalrymen and several thousand foot-soldiers against the retreating columns of Christians. At first, there were limited skirmishes with the retreating Christians, but when he realised that the enemy was preoccupied with the wagonloads of loot that they had robbed, he ordered Uthman ibn Abi al-Ula’s cavalry, the "Volunteers of the Faith", to attack in force. The Christians scattered, and the retreat turned into a rout. The Castilian-Leónese column under John’s command was taking the brunt of the attacks and he sent word to Pedro to turn back and help him. At first, Pedro was persuaded not to help John by his troops, who still had all their booty and did not want to risk losing it, but when Pedro lost his temper and ordered them to turn and fight they refused. Gathering whatever loyal troops that he could, he rode to the rear to help John. According to the chroniclers, twenty-nine years old Pedro was unhorsed in a charge and was trampled to death.

John was fighting with the master of the military orders, the Archbishop of Toledo, and the Bishop of Cordoba, and when they were told of Pedro’s death they abandoned the fight and fled. The Moors regained all their stolen goods as the Christians ran for their lives for the frontier. Knights on horse-back with full armour tried to defend themselves and their troops, but it was the hottest part of the summer and they soon fell back. Many tried to cross the Rio Genil and were drowned.

John had either suffered a heart attack or collapsed with heatstroke during the fighting, and he was put on a horse and joined the remains of the Christian army as they fled for the frontier, dropping everything in their panic. They were constantly pursued by Uthman’s 5,000 strong cavalry, who mercilessly cut them down. Pedro’s body was wrapped and put on a board to join the exodus out of Granadan lands. The retreat continued through the night, but at some point the horse carrying John became lost in the darkness. When Pedro’s body reached Baena, John’s son began to question the returning troops about the whereabouts of his father.

He soon realised that his father was lost somewhere on the battlefield and he ordered his troops to search for him. When they came back empty-handed, he sent emissaries to the Emir of Granada, who ordered his men to search. John’s body was eventually found and he was taken to Granada and placed in a coffin covered with gold cloths. The emir ordered a guard of honour made up of Moorish cavalry and Christian knights to escort the remains of Juan to the frontier where Christians took charge of the body and transported it for burial at the side of the main altar of Burgos Cathedral, where it still lies today. Pedro was also buried in Burgos, but in the monastery of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas de Burgos.

Maria de Molina was still regent for her grandson Alfonso. He would not be crowned until 1325, but she would die in 1321and never see him as king. Eight-year old Alfonso had to wait 4 years and watch as John the Traitor of Tarifa’s son, Juan the one-eyed, and Juan Manuel (the king's second-degree uncle by virtue of being Ferdinand III's grandson) carved up his kingdom in a power struggle, whilst the noble families and the Caliphate of Granada fought to take land from each other.

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08LHJGW49

A Troubled land is the second book in Joseph Puedo´s story of the reconquest. It follows Tanan, Alonso Pérez de Guzmán’s lifelong friend. He and his family have been abducted in Seville and taken to a town in the Marinid caliphate, where their abductees have hidden a fortune in gold. He is held there as a slave, but is forced to participate in the battle of Pinus Puente, where he encounters the killer of his friend’s son. He is finally released and reunited with the rest of his family in Seville, but there are still some who want to know where the gold is, and he is forced to fight a last ferocious battle for his freedom.

0

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (2)

0

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (2)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|