After nurturing her son Ferdinand until he was old enough to be crowned, it must have been a numbing loss for Maria de Molina when he died in 1312, aged 26. To prevent further bloodshed between the competing factions, she stood in again as regent of Castile for her one year-old grandson, Alfonso. It would be another 12 years until he was old enough to be crowned. Whilst the child grew to age, Maria had to allow her lifelong enemy, John of Tarifa, to become his guardian and mentor along with one of his uncles, Pedro.

The spectre of further invasions from Africa by the Marinids was still troubling the minds of many in Castile, and the pope was eager to remove Islam from Iberia altogether. In Fez, Abu Sa'id Uthman, the emir of the Marinids, was a pious and peace-loving man who was facing rebellion from his own son. In 1313, to rid himself of any further military entanglements in Iberia, Abu Sa'id returned the towns of Algeciras and Ronda to the Naṣrid ruler, Ismail I of Granada. The knowledge that the Marinids were unwilling or unable to help the Granadans inflamed the hawks and glory seekers in the kingdoms. During a meeting of the Cortez of Medina del Campo in 1318, it was decided that Pedro and Juan would lead the allied nobles to initiate another invasion with the intention of striking at the heart of the caliphate.

During the winter of 1318 supplies for the invasion were stockpiled in Córdoba and plans were drawn to have the armies assemble there in the month of June 1319. Caliph Ismail I of Granada sent an urgent appeal to the Marinid emir for assistance, but Abu Sa'id Uthman imposed such onerous conditions that the Granadans decided to face the Christians without him and began amassing their own troops on the border.

Long before the fateful meeting of Cortez of Medina del Campo, Castile had signed a non-aggression treaty with Ismail I, and the emir wrote Pedro a letter reminding him of its terms. Pedro was caught between the Cortes and his conscience, and requested that the kingdoms respect the treaty. Pope John XXII heard of his lack of commitment and threatened to excommunicate Pedro unless he led the army. Furthermore, he elevated the attack to that of Holy Crusade and offered him a portion of the tithes that the church collected on the proviso that he did not sign any further peace treaties with the emir, “Under pain of obedience and love of the Holy Eglesia.”

As with the siege of Algeciras, King Jamie II of Aragon was asked to attack on a second front in the east, not to capture territory, but to devastate the lands of the caliphate and then withdraw. The pope gave Jamie the same offer of church tithes, but Jamie refused to join the attack. When the emir heard of the threats made against Pedro he wrote another letter expressing his “Very great regret” and that he would have liked to live in peace in his own lands, but would leave the outcome to the judgement of God. Many of the Castilians were unhappy with breaking the treaty with the emir, and criticism of the attack grew in Christian lands. Nevertheless, the invasion plans went ahead unchecked.

Pedro went to Toledo to meet the troops of the Order of Santiago, Calatrava and the Archbishop of Toledo, Gutierre Gómez de Toledo. He ordered them to bring their army to readiness and to march them to the border. Next, he travelled to the city of Trujillo in Extremadura and met with the Masters of the Order of Santiago to whom he gave 3,000 doubles of gold so that the Crown could recover the castle of Trujillo, which had previously been pawned to raise money. Seville was where the siege catapults were stored, and Pedro ordered them to be transported to the border. His final meeting was with the heads of all the orders and the Archbishops of Toledo and Seville at Jienense de Ubeda, where he told them that their first objective was the Castle of Tiscar. John, who was feeling unwell, decided to stay in Córdoba.

Tiscar was chosen because, according to Pedro, it was “the strongest fortress the Moors had,” but just a few days the after the siege began, the castle surrendered. Its commander, Mahomad Handon, abandoned it and its 4,500 inhabitants left for nearby Baza, their safety guaranteed by Pedro. Tiscar was an outpost to the east of Jaen, and in the greater picture of events was a minor success. The rapid fall of Tiscar would suggest that the emir sacrificed the citadel to give Perdro something to offer the pope. He could always take it back later. However, John was now worried that Pedro was stealing the glory for the campaign with such a rapid success, so he left Córdoba and sent word for them to meet at Alcaudete.

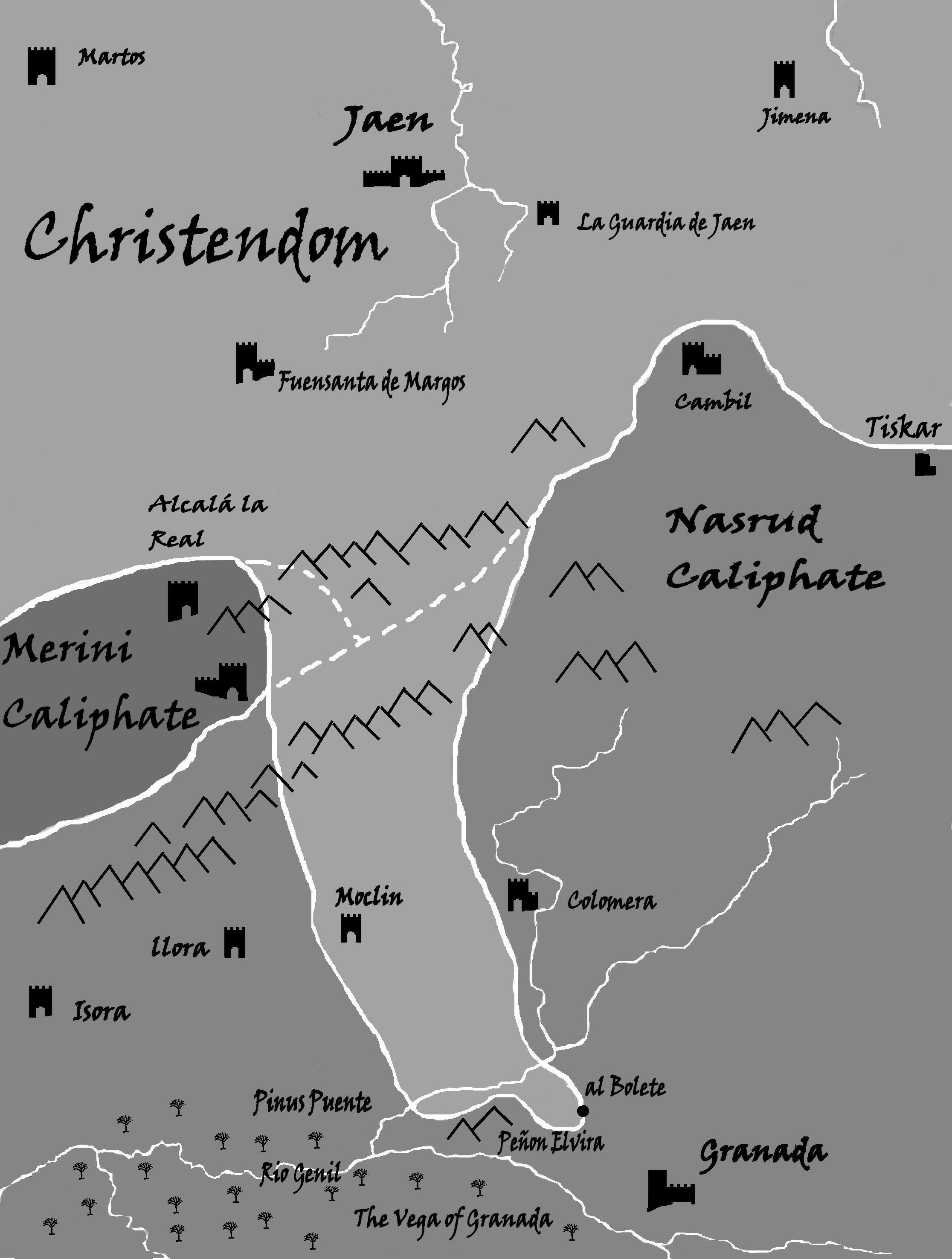

Alcaudete was on the border between the caliphate and Christendom, and John left some of his troops under the command of his son to cover their rear at Baena. He persuaded Pedro to focus their campaign on the Vega de Granada, where the looting would be more profitable, and who knows, they may even capture Granada, the greatest prize of all. The two united armies numbered around nine thousand horsemen and several thousand foot-soldiers. John decided to take the lead, and Pedro was to stay in the rear with the Master of the Orders of Santiago, Calatrava, and Alcántara, the Archbishops of Toledo and Seville, and by numerous members of the high nobility.

John drove his troops through to Alcalá la Real, where they camped overnight and the following day looted the surrounding countryside. They moved on to Moclin and Illora and rather than waste time trying to besiege the fortresses there, they bypassed them and marched on to Pinus Puente near to the confluence of three small rivers before they joined the Rio Genil. They were now nearly at the gates of Granada, and they had employed the same slash and burn tactics as used by the Marinid invasions. Juan’s troops had accumulated huge amounts of booty, but were tired and decided to camp by the rivers and rest.

A row broke out between John and Pedro when John suggested withdrawing to Christendom with their booty. Pedro was indignant that they had fought their way to Granada and were going to waste the opportunity to capture the city. John was right; they had over-extended their lines deep into the caliphate and were in danger of being cut off and surrounded. The emir could draw upon huge reserves of men, and the longer they remained, the more dangerous it would become. Relations between the John and Pedro had become so strained that they were barely talking to each other. The Christians were now in a very perilous situation. John’s plan prevailed, and the Christians began to retreat. Pedro was put in the lead of the withdrawal and John was to be the rear-guard.

General Ozmin was commander of the Granadan defence and had prepared the city for a siege. When he realised that the Christians were retreating he swiftly changed from defence to attack. He led a force of five thousand cavalrymen and several thousand foot-soldiers against the retreating columns of Christians. At first, there were limited skirmishes with the retreating Christians, but when he realised that the enemy was preoccupied with the wagonloads of loot that they had robbed, he ordered Uthman ibn Abi al-Ula’s cavalry, the "Volunteers of the Faith", to attack in force. The Christians scattered, and the retreat turned into a rout. The Castilian-Leónese column under John’s command was taking the brunt of the attacks and he sent word to Pedro to turn back and help him. At first, Pedro was persuaded not to help John by his troops, who still had all their booty and did not want to risk losing it, but when Pedro lost his temper and ordered them to turn and fight they refused. Gathering whatever loyal troops that he could, he rode to the rear to help John. According to the chroniclers, twenty-nine years old Pedro was unhorsed in a charge and was trampled to death.

John was fighting with the master of the military orders, the Archbishop of Toledo, and the Bishop of Cordoba, and when they were told of Pedro’s death they abandoned the fight and fled. The Moors regained all their stolen goods as the Christians ran for their lives for the frontier. Knights on horse-back with full armour tried to defend themselves and their troops, but it was the hottest part of the summer and they soon fell back. Many tried to cross the Rio Genil and were drowned.

John had either suffered a heart attack or collapsed with heatstroke during the fighting, and he was put on a horse and joined the remains of the Christian army as they fled for the frontier, dropping everything in their panic. They were constantly pursued by Uthman’s 5,000 strong cavalry, who mercilessly cut them down. Pedro’s body was wrapped and put on a board to join the exodus out of Granadan lands. The retreat continued through the night, but at some point the horse carrying John became lost in the darkness. When Pedro’s body reached Baena, John’s son began to question the returning troops about the whereabouts of his father.

He soon realised that his father was lost somewhere on the battlefield and he ordered his troops to search for him. When they came back empty-handed, he sent emissaries to the Emir of Granada, who ordered his men to search. John’s body was eventually found and he was taken to Granada and placed in a coffin covered with gold cloths. The emir ordered a guard of honour made up of Moorish cavalry and Christian knights to escort the remains of Juan to the frontier where Christians took charge of the body and transported it for burial at the side of the main altar of Burgos Cathedral, where it still lies today. Pedro was also buried in Burgos, but in the monastery of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas de Burgos.

Maria de Molina was still regent for her grandson Alfonso. He would not be crowned until 1325, but she would die in 1321and never see him as king. Eight-year old Alfonso had to wait 4 years and watch as John the Traitor of Tarifa’s son, Juan the one-eyed, and Juan Manuel (the king's second-degree uncle by virtue of being Ferdinand III's grandson) carved up his kingdom in a power struggle, whilst the noble families and the Caliphate of Granada fought to take land from each other.

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08LHJGW49

A Troubled land is the second book in Joseph Puedo´s story of the reconquest. It follows Tanan, Alonso Pérez de Guzmán’s lifelong friend. He and his family have been abducted in Seville and taken to a town in the Marinid caliphate, where their abductees have hidden a fortune in gold. He is held there as a slave, but is forced to participate in the battle of Pinus Puente, where he encounters the killer of his friend’s son. He is finally released and reunited with the rest of his family in Seville, but there are still some who want to know where the gold is, and he is forced to fight a last ferocious battle for his freedom.