Can't sleep in the heat...try it in chain mail pyjamas.

Friday, June 18, 2021

For 400 years the walled fortress of Calatrava la Vieja stood on the frontier between Muslim and Christian lands. Its name was derived from the name of the Arab nobleman, Qalʿat Rabāḥ, who founded it sometime after 785. Towering over the Guadiana River valley, the fortress held great strategic importance by controlling the roads to the rival taifas of Córdoba and Toledo who fought each other and the taifa of Seville for its control. During these internal battles it was partially destroyed and rebuilt again by al-Hakam, son of Abd ar-Rahman II.

Calatrava la Vieja.

It was the Umayyad Caliphs of Córdoba who were in control of the fortress when it was attacked and captured by King Alfonso VII (el Emperador) in 1147, but it was at the extreme southern edge of the Christian kingdoms and it was inevitable that its ownership would be hotly contested. There is an old saying; you can have what you can take, but you can only keep what you can hold. This was true for the fortress of Calatrava. In those days there was no such thing as a standing army of troops who would defend the Christian kingdoms. Armies were raised on the offer of plunder and possible land gain for the dukes who were obliged to provide the king with men for a fixed term and to feed them. This was an onerous financial burden if you were only providing a garrison. However, the need for a unified force of soldiers during the reqonquista was obvious, and there was a precedent that had proved its worth and grown rich and powerful in the process..

When the First Crusade had captured Jerusalem from the Muslims in 1099 Christians flocked to make the pilgrimage to the Holy Land and Jerusalem. Higwaymen and bandits attacked these pious but wealthy pilgrims sometimes robbing and killing them by the hundreds. The point came when something had to be done to protect these innocent people, and it was a French knight who came up with the idea of creating a monastic order to protect the pilgrims. In 1119 Hugues de Payens approached King Baldwin II of Jerusalem and explained his idea. Early the following year at the Council of Nablus, Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem, granted the Frenchman his wish.

Initially the order was founded with just nine knights including Godfrey de Saint-Omer and André de Montbard. For a headquarters they were given a wing of the royal palace on the Temple Mount in the captured Al-Aqsa Mosque. The Temple Mount was believed to have been the site of the Temple of Solomon, and the new order became known as the Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, which was shortened to just the “Templars.” They had no financial backing and relied upon donations to survive. Their emblem was of two knights riding on a single horse, emphasizing the order's poverty.

Fifty years later, the Order of the Knights Templar had grown to a sizable army with quite impressive assets and funding, and it was they who were given the task of defending the captured fortress of Calatrava. For reasons unknown, the Templars did not stay long, and King Sancho III of Castile made a public offer to give the castle and surrounding land to any group who would defend it for him. This prompted a retired soldier called Diego Velásquez who had become a monk at the monastery of Fitero to speak to his abbot, Raymond. Cistercian monks were not warriors, so Diego proposed forming an army of defenders from the lay-brothers of the order. Lay-brothers were a recent addition to Cistercian monasteries which had found the need to allow tradesmen into their monasteries. Whilst the monks performed more pious duties, the lay-brothers looked after the cattle and sheep and maintained the buildings. They did not wear habits and had taken no religious vows, and must have been very happy that they had landed a plum job for life. Monasteries then were oases of sanity and safety whilst the hatred and brutality of the requonquista raged around them. When Diego suggested that they become Soldiers of the Cross they must have been overjoyed. However, the lay-brother loophole allowed Raymond to hire another kind of tradesmen, those who lived by the sword. Raymond went to his superior, Juan II of Toledo, the Archbishop of Toledo, who backed him to the hilt, creating the new Order of Calatrava in 1157. As it turned out, the first test for the order of would arrive the very next year.

The winds of change were blowing from Africa, and ten years earlier a new wave of Moors had subdued all of the Maghreb and crossed the straits into Iberia. The Almohads were a more orthodox Muslim sect who were determined to impose a stricter interpretation of the Koran on the Almoravids. In 1158 they made an attempt to take the fortress of Calatrava, but were beaten back by the Calatravans under the command of the Archbishop. The fortress remained under the control of the Calatravans for the next 36 years, but Raymond died in 1163 and was succeeded by a man whose history is unknown. Known only as Don Garcia, he must have been highly thought of by the king, who installed him as the first grand master of the order, forcing Velasquez into a secondary role. Garcia transformed the order into a private army. Under his rule, the monks were moved (under protest) to the monastery of Cirvelos, leaving just the knights under the command of Velasquez and a few other clerics to defend the fortress. The order attracted more mercenary knights and pious nobles willing to fund and fight the reqonquista. To give the order legitimacy with the church, and a formal code of conduct, a general chapter in 1187agreed upon the code for the Knights of Calatrava which was approved by Pope Gregory VIII. They were to be lay brothers following the Cistercian rules of silence in certain areas of the monastery, abstinence four days of the week, and to have several fast days during the year. More pertinent to their military role, they were to sleep in their armour and to wear the Cistercian white mantle with a black cross called the Flordelisada, which would later be changed to red.

A knight of the Order of Calatrava. Painting: A Pearson. alanpearson.pixels.com

Meanwhile, the power and forces of the Almohads had grown, and in 1195 they attacked the principle Christian town of town of Alarcos on the river Guadiana. King Alfonso VIII brought an army to the defence of the town, but he was defeated by Caliph Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur, who immediately began to occupy the surrounding territory. The first fortress to fall was Calatrava, and for the next seventeen years the frontier lay in the hills to the south of Toledo.

In 1212 Pope Innocent III called for a crusade against the Almohads, and the kingdoms rallied around his flag. The Catalans and Aroganese led by Peter II, the Franks led by the Archbishop of Narbonne and the Navarrese led by Sancho VII. The military orders also gave their support, including the Calatravans and Templars. The citadel of Calatrava was the first major objective to be recaptured followed by Alarcos and Benavente before the final battle at las Navas de Tolosa near Santa Elena, which broke the power of Muhammad al-Nasir and the Almohads.

But the story of Calatrava was not over. When the pope called for the crusade he assembled the troops of his coalition in Toledo where they immediately began to fall out with each other. The French and other Europeans were unused to the heat of the Iberian summer, but whilst they were camped around Toledo they were responsible for assaults and murders in the Jewish quarter of the town. When they took Calatrava, they wanted to slaughter the Jews and Moors who had lived in and defended the fortress and take their wives and children as slaves. Alfonso VIII had ordered the humane treatment of all the defenders and their families, as was common during the requonquista. This was not the kind of crusade the mercenary troops had signed up for and more than 30,000 men broke camp and deserted to cross back over the Pyrenees.

The final part of the story of the fortress of Calatrava came in 1217 when the frontier had been pushed back and the order moved 60 km to the south to the castle of Dueñas, which became known as Calatrava la Nueva, and the old Calatrava became known as Calatrava la Vieja.

Calatrava la Nueva

It’s one thing to read about history from dusty old books and piece together events from disjointed records, and another to be able hold the past in your hands.

In 1960 a farmer uncovered a buried stash of over 100 coins from the ninth century at what would then have been the eastern edge of Calatrava la Vieja. Archaeologists arrived on the scene too late to stop the farmer selling all but five coins, which he donated to the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid.

A second find came in 1995 during construction work close the first site, but this time the finder informed the Department of Pre-History, Archeology and Ancient History at Madrid’s Complutense University. The stash contained 400 grams of silver coins from the reigns of “all of the Umayyad Emirs of al-Andalus from Abd al-Rahman I to Abd Allah, plus a few fragments of Frankish coins, two coins from other Islamic dynasties and two small pieces of silver jewellery.” The chronology of the coins covers more than 100 years, from the late 700’s to 891 or 892 and they are now displayed Provincial Museum of Ciudad Real. A third find by archaeologists came in 2004 near to the alcázar fortress at Old Calatrava. 71 coins were uncovered by wrapped in fragments of cloth and had probably been hidden in the roof timbers of a house which collapsed sometime after 1217. The value of the coins is believed to have been around a month’s wages when they were hidden. A final find came in 2010 just eight meters from the previous one and contained 29 coins. These were minted between 1200 and 1264 and had also been hidden in the roof of a house.

The people who hid this money were hoping to return and collect it again, but in the uncertain and often brutal times in which they lived they often did not survive the frequent attacks and changes of ownership that plagued old Calatrava. Whole families would either be killed or sold into slavery as one warring faction replaced another.

The last part, including the photos of coins, is taken from an article in El Pais entitled Calatrava la Vieja’s hidden coins, and was authored by the archaeologist Manuel Retuerce Velasco and others.

3

Like

Published at 9:00 AM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 9:00 AM Comments (0)

The tunnel of spies.

Friday, June 4, 2021

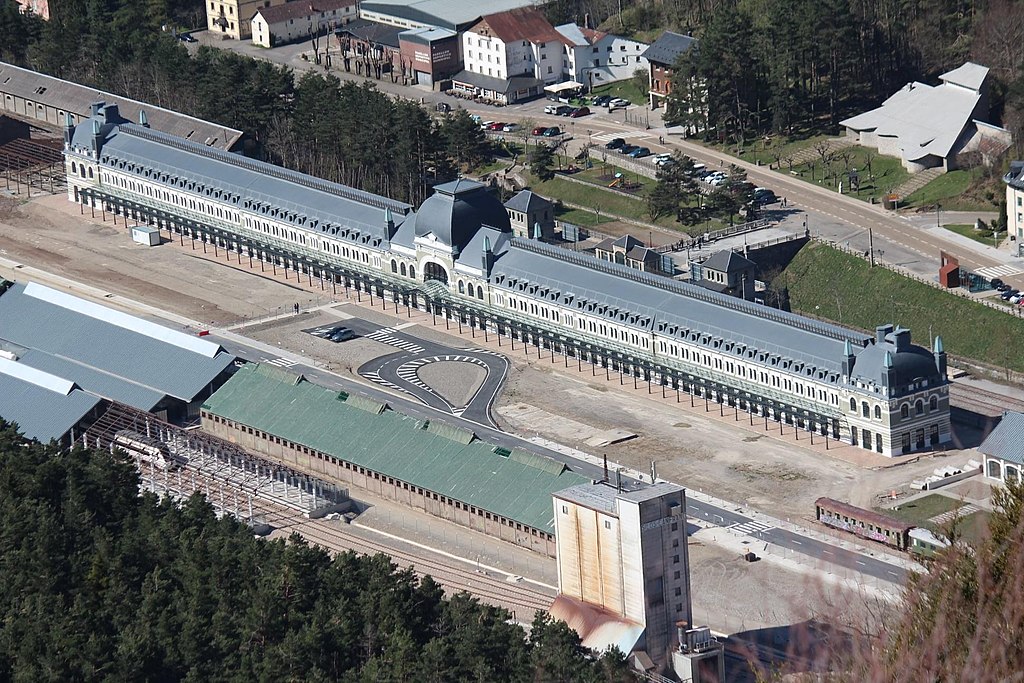

After the end of the First World War, during the euphoria following one of the most awful periods of world history, the Pau-Somport rail tunnel had been driven beneath the Pyrenees to link France with Spain by rail. It was to be a hope for the future prosperity of both countries. The Spanish spared no expense to create a welcome for visitors to their country and built a Beaux-art station concourse 240 meters long with 365 window and 156 doors. It was to be a hub for rail traffic, both passenger and freight arriving from the north of Europe. However, Estación Internacional de Canfranc, as it became known, was not a through station. It was a dead end from both sides.

The station had been built with extensive facilities for transferring the passengers and freight from one set of lines to another adjacent set of lines. This was because the 1,435 millimetres (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) French gauge was incompatible with the Spanish gauge of 1,668 millimetres (5 ft 5 21⁄32 in). Despite this setback, hopes were high that traffic would flow quickly and freely from one country to the other. Canfranc International was opened in July 1928, but events were already darkening the skies on both sides of the Pyrenees. In August 1934, Adolf Hitler became dictator of Germany and two years later the Spanish Civil war began. Franco ordered the tunnel entrance on the Spanish side to be walled up to stop the loyalists bringing reinforcements through it. The dream of easy travel and friendly relations with the rest of Europe looked to be doomed; and so they were until the end of the Civil War in Spain.

The derelict station of Canfrank in the 90's. Photo: Jean-Pierre Bazard.

With the Civil War over, the tunnel was opened once again, but Canfranc became the hub for some very different activities to tourism. On the French side was Vichy France, ruled by a puppet government under German control. On the Spanish side was a country under the heel of a dictator with its population near to starvation and bankruptcy.

Germany was rounding up Jews for extermination camps, and many organisations were rescuing Jewish families by giving them false papers and sending them to neutral Spain where they could claim asylum. In Budapest, the Spanish Ambassador, Angel Brits, had discovered a legal loophole that allowed him to issue Jewish families with papers that entitled them to move to Spain as residents. The old law of 1924 applied to the Sephardic Jews expelled during the reign of Isabel and Ferdinand and had been repealed in 1930, but the Germans didn’t know that. Many of these refugees arrived on the platform at Canfranc and were met by Albert Le Lay, the head of the French Customs, and a member of the French Resistance, who passed them on to sympathetic Spanish consulate staff. Something like 14,000 fugitives from the Nazis passed safely through Canfranc. Surviving station workers still boast that not one refugee was ever handed over to the Germans.

There were other kinds of escapees, too. Allied airmen who had been shot down over France were sometimes smuggled aboard the trains and they too were spirited away from the platforms as they arrived. Perhaps the least dangerous, but most rewarding for the families who lived around Canfranc was in the memories of the children of the village who recall their father arriving home from work at the railway goods yard with pockets stuffed with tinned sardines or fruit which, according to their fathers, had been found lying at the side of the track. The Canfranc men earned a local reputation of being able to steal the shoes from a running horse.

However, it was the movement of mining ore trucks that filled the long platform of Canfranc with some of the most sinister and evil people of that awful time. The movement of refugees and airmen would be enough to bring the German SS here, but the freight was several magnitudes higher in importance, and the area around Canfranc was watched by dozens of German officers, who in turn were watched by Allied spies, and on occasion, representatives of neutral Switzerland. In in the corridors of MI6 and the American intelligence agencies tasked with depriving the Nazis of essential war materials, Canfranc had been dubbed “The Casablanca of the Pyrenees.”

The reason for this espionage was because a vital element was needed by Germany that could only be found in quantity in isolated mines in Portugal and Spain. The Germans first discovered the ore and called it wolfram, but the refined element within the ore is known as tungsten. Tungsten is used as an alloy in steel for cutting tools that were essential for German war production. Large shipments of wolfram began passing through the tunnel on their way to Germany, whilst coming in the opposite direction, shipments of German gold looted from all Europe arrived in Spain to pay for the wolfram.

Throughout the Second World War, Spain was subject to economic sanctions by the Allies to stop the supposedly neutral country aiding the Axis countries with the shipment of war materials. The US stopped the supply oil to Spain, and the Royal Navy enforced the blockade at sea. During the Battle of Britain, when it looked likely that England would fall, Franco was tempted to come into the war on Germany’s side. In Spanish history this is called “the great temptation,” and Britain and America increased their sanctions against Spain to persuade Franco not to. When Roosevelt sold Britain 50 destroyers (old and out of date) under the lend lease scheme Franco was swayed and considered the heavy penalties that his starving and bankrupt country would pay if he joined the Axis powers. At the same time, America offered Franco some very attractive loans. The carrot and stick policy worked and Franco stayed out of the war.

Meanwhile, both America and Britain, who also wanted wolfram, began a bidding war for the vital ore. Spain was only the second largest producer of wolfram during the war, and most of the production came from the Panasqueira mine in Portugal. Ironically, the mine had been British owned before the war. The long-serving dictator of Portugal, António de Oliveira Salazar, began a dangerous game of trying to please to Allies and Nazis at the same time, as both sides made threats and offers for the control of the vital ore. It was too dangerous to send the wolfram by sea, so the ore from both countries was sent by rail through the Estación Canfranc.

When the Spanish Civil war ended in 1939, exports of wolfram earned Spain £73,000 a year, but as the world superpowers began to bid against each other the price ballooned, and by 1943, exports of wolfram were bringing Spain a staggering £15.7 million a year, which accounted for 20% of Spain’s total export revenue. Franco was happy to play both sides off against each other until 1943, when the American ambassador ordered the unconditional halt of wolfram exports to Germany otherwise it would stop all oil supplies to Spain, and also stop all other exports from leaving Spain. Franco grudgingly complied, but continued to supply Nazi Germany with limited amounts of wolfram in great secrecy. Knowing full well of the double-cross, Winston Churchill was obliged to commend Spain for its “services” in the House of Commons.

It was only in 2000 when a French citizen found documents that recorded the passage of 86 tons of Nazi gold through Canfranc between 1942 and 1943 that the true scale of the operations that went on at Canfranc became known. Pensioners who live in Canfranc now remember their parents telling them how the French and Spanish border guards worked together, but the Germans made no friends and kept themselves to themselves. Some of the guards at Canfranc were often ordered to escort the gold shipments as far as Portugal.

After the war, the rail service was resumed until 1970 when the tunnel was closed on the French side after a derailment destroyed a bridge, and the tracks were declared unsafe for use. There was by now not enough traffic to justify the repairs, and the line to Canfranc was closed. Nowadays the Estación Canfranc is still home to people dealing with dark matters, but they are scientists studying the dark matter in intergalactic space. The 850m of rock of Monte Tobazo above the Pau-Somport tunnel filters out many of the particles that would otherwise ruin a search for the mysterious substance. The Laboratorio Subterráneo de Canfranc is open to the public, and in 2018 it received 2,400 visitors.

The newly refurbished Canfranc Station. Photo: Antonio Orga

However, the idea of re-opening the tunnel to rail traffic again has gained the approval of the EU, who several years ago allocated funds for the restoration of the station for its “enormous historical and monumental value,” with the ultimate aim of opening the tunnel and re-establishing rail services bringing tourism and allowing the passage of trade goods once again. The effects on the local economy and the economy of Aragon could be very beneficial. To this end, on April15, 2021, a RENFE DMU carrying invited guests from Zaragoza became the first train to arrive at the remodelled and relocated station in Canfranc.

Who knows, perhaps this beautiful station could finally become the iconic Estación Internacional that it was meant to be.

5

Like

Published at 9:00 AM Comments (2)

5

Like

Published at 9:00 AM Comments (2)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|