After the end of the First World War, during the euphoria following one of the most awful periods of world history, the Pau-Somport rail tunnel had been driven beneath the Pyrenees to link France with Spain by rail. It was to be a hope for the future prosperity of both countries. The Spanish spared no expense to create a welcome for visitors to their country and built a Beaux-art station concourse 240 meters long with 365 window and 156 doors. It was to be a hub for rail traffic, both passenger and freight arriving from the north of Europe. However, Estación Internacional de Canfranc, as it became known, was not a through station. It was a dead end from both sides.

The station had been built with extensive facilities for transferring the passengers and freight from one set of lines to another adjacent set of lines. This was because the 1,435 millimetres (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) French gauge was incompatible with the Spanish gauge of 1,668 millimetres (5 ft 5 21⁄32 in). Despite this setback, hopes were high that traffic would flow quickly and freely from one country to the other. Canfranc International was opened in July 1928, but events were already darkening the skies on both sides of the Pyrenees. In August 1934, Adolf Hitler became dictator of Germany and two years later the Spanish Civil war began. Franco ordered the tunnel entrance on the Spanish side to be walled up to stop the loyalists bringing reinforcements through it. The dream of easy travel and friendly relations with the rest of Europe looked to be doomed; and so they were until the end of the Civil War in Spain.

The derelict station of Canfrank in the 90's. Photo: Jean-Pierre Bazard.

With the Civil War over, the tunnel was opened once again, but Canfranc became the hub for some very different activities to tourism. On the French side was Vichy France, ruled by a puppet government under German control. On the Spanish side was a country under the heel of a dictator with its population near to starvation and bankruptcy.

Germany was rounding up Jews for extermination camps, and many organisations were rescuing Jewish families by giving them false papers and sending them to neutral Spain where they could claim asylum. In Budapest, the Spanish Ambassador, Angel Brits, had discovered a legal loophole that allowed him to issue Jewish families with papers that entitled them to move to Spain as residents. The old law of 1924 applied to the Sephardic Jews expelled during the reign of Isabel and Ferdinand and had been repealed in 1930, but the Germans didn’t know that. Many of these refugees arrived on the platform at Canfranc and were met by Albert Le Lay, the head of the French Customs, and a member of the French Resistance, who passed them on to sympathetic Spanish consulate staff. Something like 14,000 fugitives from the Nazis passed safely through Canfranc. Surviving station workers still boast that not one refugee was ever handed over to the Germans.

There were other kinds of escapees, too. Allied airmen who had been shot down over France were sometimes smuggled aboard the trains and they too were spirited away from the platforms as they arrived. Perhaps the least dangerous, but most rewarding for the families who lived around Canfranc was in the memories of the children of the village who recall their father arriving home from work at the railway goods yard with pockets stuffed with tinned sardines or fruit which, according to their fathers, had been found lying at the side of the track. The Canfranc men earned a local reputation of being able to steal the shoes from a running horse.

However, it was the movement of mining ore trucks that filled the long platform of Canfranc with some of the most sinister and evil people of that awful time. The movement of refugees and airmen would be enough to bring the German SS here, but the freight was several magnitudes higher in importance, and the area around Canfranc was watched by dozens of German officers, who in turn were watched by Allied spies, and on occasion, representatives of neutral Switzerland. In in the corridors of MI6 and the American intelligence agencies tasked with depriving the Nazis of essential war materials, Canfranc had been dubbed “The Casablanca of the Pyrenees.”

The reason for this espionage was because a vital element was needed by Germany that could only be found in quantity in isolated mines in Portugal and Spain. The Germans first discovered the ore and called it wolfram, but the refined element within the ore is known as tungsten. Tungsten is used as an alloy in steel for cutting tools that were essential for German war production. Large shipments of wolfram began passing through the tunnel on their way to Germany, whilst coming in the opposite direction, shipments of German gold looted from all Europe arrived in Spain to pay for the wolfram.

Throughout the Second World War, Spain was subject to economic sanctions by the Allies to stop the supposedly neutral country aiding the Axis countries with the shipment of war materials. The US stopped the supply oil to Spain, and the Royal Navy enforced the blockade at sea. During the Battle of Britain, when it looked likely that England would fall, Franco was tempted to come into the war on Germany’s side. In Spanish history this is called “the great temptation,” and Britain and America increased their sanctions against Spain to persuade Franco not to. When Roosevelt sold Britain 50 destroyers (old and out of date) under the lend lease scheme Franco was swayed and considered the heavy penalties that his starving and bankrupt country would pay if he joined the Axis powers. At the same time, America offered Franco some very attractive loans. The carrot and stick policy worked and Franco stayed out of the war.

Meanwhile, both America and Britain, who also wanted wolfram, began a bidding war for the vital ore. Spain was only the second largest producer of wolfram during the war, and most of the production came from the Panasqueira mine in Portugal. Ironically, the mine had been British owned before the war. The long-serving dictator of Portugal, António de Oliveira Salazar, began a dangerous game of trying to please to Allies and Nazis at the same time, as both sides made threats and offers for the control of the vital ore. It was too dangerous to send the wolfram by sea, so the ore from both countries was sent by rail through the Estación Canfranc.

When the Spanish Civil war ended in 1939, exports of wolfram earned Spain £73,000 a year, but as the world superpowers began to bid against each other the price ballooned, and by 1943, exports of wolfram were bringing Spain a staggering £15.7 million a year, which accounted for 20% of Spain’s total export revenue. Franco was happy to play both sides off against each other until 1943, when the American ambassador ordered the unconditional halt of wolfram exports to Germany otherwise it would stop all oil supplies to Spain, and also stop all other exports from leaving Spain. Franco grudgingly complied, but continued to supply Nazi Germany with limited amounts of wolfram in great secrecy. Knowing full well of the double-cross, Winston Churchill was obliged to commend Spain for its “services” in the House of Commons.

It was only in 2000 when a French citizen found documents that recorded the passage of 86 tons of Nazi gold through Canfranc between 1942 and 1943 that the true scale of the operations that went on at Canfranc became known. Pensioners who live in Canfranc now remember their parents telling them how the French and Spanish border guards worked together, but the Germans made no friends and kept themselves to themselves. Some of the guards at Canfranc were often ordered to escort the gold shipments as far as Portugal.

After the war, the rail service was resumed until 1970 when the tunnel was closed on the French side after a derailment destroyed a bridge, and the tracks were declared unsafe for use. There was by now not enough traffic to justify the repairs, and the line to Canfranc was closed. Nowadays the Estación Canfranc is still home to people dealing with dark matters, but they are scientists studying the dark matter in intergalactic space. The 850m of rock of Monte Tobazo above the Pau-Somport tunnel filters out many of the particles that would otherwise ruin a search for the mysterious substance. The Laboratorio Subterráneo de Canfranc is open to the public, and in 2018 it received 2,400 visitors.

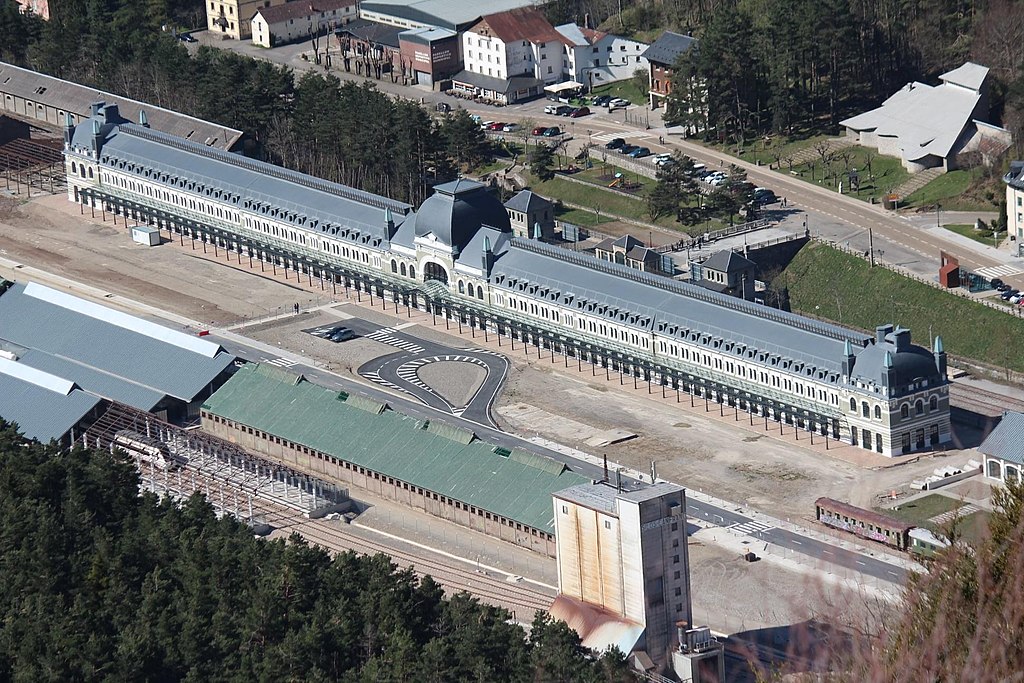

The newly refurbished Canfranc Station. Photo: Antonio Orga

However, the idea of re-opening the tunnel to rail traffic again has gained the approval of the EU, who several years ago allocated funds for the restoration of the station for its “enormous historical and monumental value,” with the ultimate aim of opening the tunnel and re-establishing rail services bringing tourism and allowing the passage of trade goods once again. The effects on the local economy and the economy of Aragon could be very beneficial. To this end, on April15, 2021, a RENFE DMU carrying invited guests from Zaragoza became the first train to arrive at the remodelled and relocated station in Canfranc.

Who knows, perhaps this beautiful station could finally become the iconic Estación Internacional that it was meant to be.