A Traitor's Triumph.

Saturday, November 28, 2020

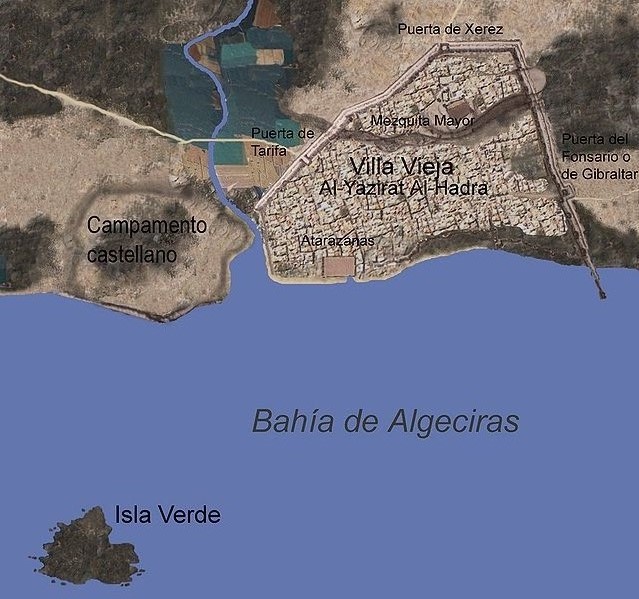

By 1308 Alonso Pérez de Guzmán was a very wealthy man. His loyalty had been tried and tested and his prowess in battle was legendary. Noblemen were expected to be able to raise an army from their own lands and lead them into battle. Each lord and landowner had a duty to donate fighting men and arm and feed them should their duke require it. King Ferdinand and his mother feared other invasions from Africa. They held Tarifa, but the real danger was from an army landing at the now Nasrid held ports of Gibraltar or Algeciras. Since the reign of Alfonso X, these two ports had held the key to defending Christendom.

In late 1308, at Alcalá de Henares, King Ferdinand IV of Castile and the ambassadors from the Crown of Aragon, agreed to the terms of a new treaty. Ferdinand, supported by his brother, Pedro de Castilla y Molina, the archbishop of Toledo, the bishop of Zamora, and Diego López V de Haro agreed to wage war against the Caliphate of Granada. The previous treaty between Granada and Castile was set to expire at the end of June 1309, and Ferdinand, instigated a new round of war against the Moors. To avoid the possibility of betrayal, it was also agreed that James II of Aragon would not be allowed to sign a separate peace accord with the Emir of Granada, and that a combined Aragonese-Castilian navy would be formed to support the siege. It was also agreed that James II would simultaneously launch an attack on Almaria, giving the Nasrids two fronts to defend. On 29 April 1309, Pope Clement V issued the papal bull Prioribus decanis which officially conceded to Ferdinand IV one 10th of all clergy taxes collected in his kingdoms for three years to aid in financing the campaign against Granada.

In return, Ferdinand IV promised to cede one sixth of the conquered Granadan territory to the Aragonese crown. Some of the king’s nobles were not happy with this arrangement, notably John, the Traitor of Tarifa. After the signing of the treaty, the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon sent emissaries to Pope Clement V to give the enterprise the official stamp of Holy Crusade. In 1309, for the very first time, the Cortez was held in Madrid, where King Ferdinand declared war on the Caliphate of Granada and requested that his dukes assemble their armies. John of Tarifa was to assist with the siege of Algeciras along with his son.

Old Moorish battlements above Gibraltar. Old Moorish battlements above Gibraltar.

Guzmán was assigned to the siege of Gibraltar along with Juan Núñez II de Lara, the Archbishop of Seville and Garci López de Padilla, the grand master of the Order of Calatrava. Their troops were drawn from the militia councils of Seville and noblemen of that city. In The Chronicles of Ferdinand IV the historian writes that Guzmán spent some weeks at the beginning of the siege building two low stone towers on which he placed engeños. It’s not clear what these weapons were, but it’s entirely possible that Guzmán was using cannons for the first time in Europe. The defenders lasted a few weeks before they were forced to surrender the city. Guzmán and Lara allowed the Moors to leave unharmed, ending a Muslim occupation of Gibraltar that had lasted 600 years. King Ferdinand ordered the rebuilding of the fortifications of Gibraltar and the building of a new dock where ships could be repaired.

Meanwhile, the siege of Algeciras was dragging on without success. The siege had begun in July, but before long, so many men and horses in one place made the living conditions in the Christian camp appalling. The River Andarax became little more than an open sewer, and as the summer turned to autumn, torrential rain turned their camp into a quagmire. King Ferdinand was late in paying his troops, and John of Tarifa incited a rebellion. Five hundred knights led by John, and backed by Alfonso de Valencia, Don Juan Manuel and Fernán Ruiz de Saldaña deserted. The news of this betrayal spread throughout Castile and provoked indignation. James II of Aragon rode after John to try to persuade him to return and fight, but John refused all pleas.

King Ferdinand still had the support of Guzmán, Juan Núñez II de Lara, and Diego Lopez V de Haro and they agreed to continue the siege, but money was running short, and King Ferdinand was forced to sell his wife’s jewellery to pay his troops. They were reinforced by large army sent by Felipe de Castilla y Molina and another sent by the Archbishop of Santiago de Compostela, who arrived at the head of 400 knights and a great number of foot-soldiers.

Guzmán moved to the mountains north of Algeciras where the Nasrids were attacking the besieging army, and it was whilst he was pursuing a group of enemy troops near the town of Gaucin that he was mortally wounded by an arrow.

His body was brought back to Seville by his troops, who marched as a guard of honour. He was interred in the Monastery of San Isidoro del Campo overlooking the river Guadalquivir just outside Seville, near to the Roman town of Itálica. He and his wife had prepared their own last resting place in 1301 by converting and renaming an old Moorish mosque and establishing a monastery there. It was named after a canonised bishop of Seville. Later, A second nave was added to the original, and the monastery gained the less formal name of Los Gemelos. (The twins) Alonso’s son, Juan, now took on his father’s title, and it was Juan who had the body of his father buried on the left side of the alter, and much later, his mother on the right.

With the Caliphate of Granada and the Kingdom of Castile nearly bankrupted by the campaign, both sides signed another peace treaty, the terms of which were heavily in favour of the Christians. The emir had lost the respect of his troops and generals by agreeing to the Christian demands, and when he discovered a plot to have him assassinated, he quickly returned to Granada. He found that he was equally unpopular there, and his brother, Nasr Abul Geoix, had installed himself as emir. Muhammed III was made to watch his prime minister murdered and his palace plundered. He abdicated in favour of his brother shortly afterwards.

Things were not much better in Gibraltar. Conquered towns were difficult to repopulate and when the Moors left, the town was virtually empty of people. The king appointed Alfonzo Fernando de Mendoza as governor, but a year after it had been captured it was still unoccupied and useless as a port. Ferdinand offered incentives for people to move into the town. One of the incentives was that:

All swindlers, thieves, murderers and wives escaped from their husbands could have refuge in the city and be free of any prosecution from the law, including the penalty of death. (although this last provision did not extend to traitors to the crown.) He also abolished all duties on goods passing in or out of the port. The lifting of prosecution laws was to be used again throughout the repopulation of the rest of al-Andalus, and the kind of people who trickled into Gibralter dissuaded other honest traders and families from settling there. These rejects from society became known as Homicinos, and they began to fill the empty towns as the Moors were expelled.

There was one last casualty to this war. In the terrible conditions of the siege of Algeciras, Diego Lopez V de Haro had become ill and subsequently died. He was the current Lord of Biscay, and John, the traitor of Tarifa and Algeciras, who had long coveted this title, was able to install his wife as Lady of Biscay. But John’s ambition was to be his undoing when he led Christian forces on the next round of the reconquest of Iberia.

3

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (1)

3

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (1)

Something fishy this way comes

Saturday, November 21, 2020

The gifts of towns and ports, firstly by King Alfonso X, then Sancho IV had given Alonso Pérez de Guzmán and his family a sizable income. Maria’s dowry had brought vineyards and flourmills around Seville, and when he left Morocco behind for good, he began buying land that the Marinid invasions had left desolate and depopulated. The Cortez was a battleground where he was outgunned by the likes of Pedro Ponce de León, who controlled the finances of the kingdom. Pedro and his brother owned lands adjacent to Guzmán’s and were eager to extend their territory. There were other powerful families jostling for favour with Maria de Molina and King Ferdinand, and the ever perfidious, John, the Traitor of Tarifa, wove his webs of intrigue amongst all of them.

Guzmán had faithfully served three kings of Castile now, and Maria de Molina knew that he was unhappy in her court. Much of western Iberia had been abandoned, and the people had moved north of Seville where the African invasions rarely reached. The territory that Guzmán owned was unproductive and lawless, but before the invasions it had been a very rich and fertile area that had supported Moors and Christians for centuries. The Order of Calatrava had been given charge of the lands around Huelva and Niebla, but they were too busy hatching plots against each other to bring stability to the west coast. Maria was very clever, and knew where the money was. She released Guzmán and gave him the gift of the almadrabas of Conil and Chiclana. The Calatravans had been running the almadrabas, and she suspected that a lot of the money that they earned was not appearing as revenue in the coffers of her kingdom.

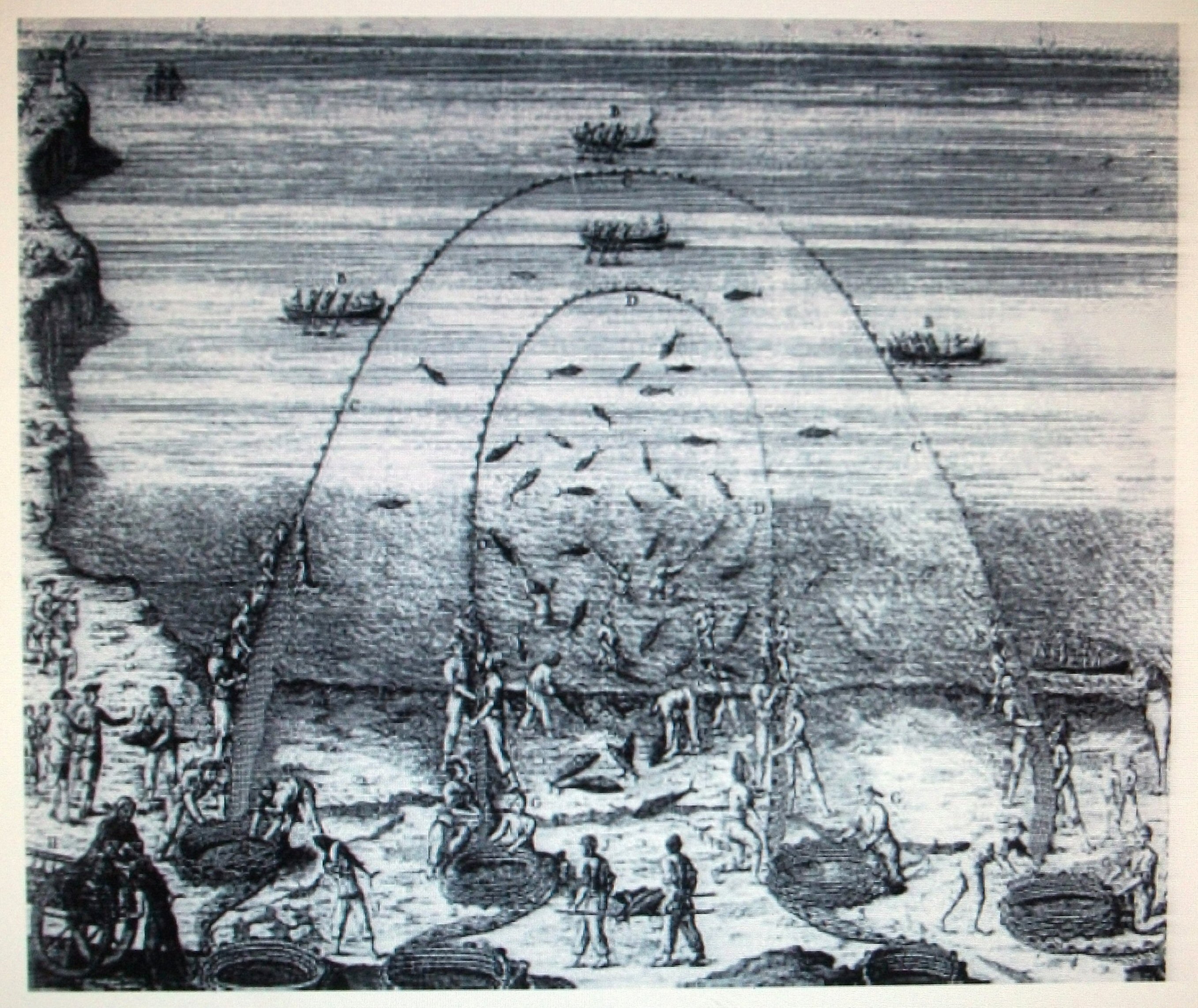

For thousands of years the fishermen of the west coast of Iberia had reaped a harvest from the Atlantic Ocean between the first full moon in May and the end of July. Far out in mid-Atlantic, Bluefin Tuna that had fed all winter began to migrate down the Iberian coast to enter the Mediterranean and spawn. They came in their hundreds of thousands and were pursued by the most ferocious hunters in the sea; killer whales. Knowing that the huge Orcas could not come into shallow water by the beaches, the tuna shoaled close to the shore. This is where the fishermen laid their traps to catch them. Down the west coast, and through the straits, teams of fishermen laid out elaborate systems of nets. The traps were only effective on a gently sloping beach with no underwater obstacles. There were several small traps such as Sancti Petri and Castilnova, Cadiz, and Huelva, but by virtue of their beaches, the biggest and most productive were at Chiclana, Barbate, Zahara, Conil and Tarifa.

The tira, or looped nets system of catching the tuna.

When Guzmán arrived at Conil he discovered a meticulously planned and executed operation for catching the huge fish. A cabal of highly skilled fishermen, who knew the ways of the atun, organised the hundreds of itinerant workers who arrived every year at Huelva to work in the traps. At the same time, the salinas dotted up and down the coast loaded their salt onto wagons and began to deliver it to the fishing sites. Carpenters around Donaña and Bollullos began cutting Holm Oak to repair boats and make oars, whilst others cut cork for floats for the nets. Willow hoops for the barrels were made by highly skilled tradesmen in Rocinas, and all these essential products were delivered to the beaches where the men who would cut up, salt and pack the huge fish were setting up their trellises and tables. Nets were made or repaired in warehouses in Huelva and shipped to the traps, where they were coiled on the beach ready to be pulled into the sea. Last of all, a group of men spread out along the coast and climbed small stone towers dotted along the cliffs from Chiclana to Barbate. Each tower was in sight of the next, and the men donned their sombreros and waited for the tell-tale thrashing of the water and the high pointed fins of the Orcas as they herded the tuna down the coast. Once the watchmen sighted this, they raised flags, and the boats pulled out the nets to catch the terrified fish.

As soon as the first fish were hauled out of the surf the dealers arrived in their ornate and expensive wagons. They travelled in their finery, with each covered wagon equipped with sofas, tables, crockery and stoves for heating and cooking. They set up camp away from the poor fishermen’s tents and only came to the chanclas, where the butchers worked to bid for the finest cuts of flesh. It was obvious where all the money was going. Some of the traders had come from as far away as Valencia and the north coast of Iberia to buy the choicest cuts. A few were selling to the private armies and navy of Iberia and some to other kingdoms in France and Italy. Armies march on their stomachs, and a navy on patrol cannot stop to augment its supplies by fishing. The logistics of supplying troops and sailors required a varied diet, and oily fish like tuna was a necessary supplement. If it was salted and sealed in barrels, it could keep for months. Everything was organised to the last detail. The only thing missing was the bookkeeping.

This tiled picture can be seen in Conil and shows the almadraba fishermen.

Guzmán decided to take a hand in every aspect of the trap. He waded into the surf with the paraleros who pulled the thrashing fish out of the water with iron hooks, and helped uncoil the nets as the boatmen pulled them into position. He befriended the quiet men who organised everything on the water and gained their confidence and trust. He became known as the Duke of the Almadrabas. Ten weeks later, all the tuna had passed, and the fishermen received their pay.

An average catch for a season at Conil was 16,000 tuna, and the fish were bought by the traders for around 8 marvaledís each, which means that the income was 128,000 marvaledís. Chiclana would probably bring in the same number of tuna, so the total income for the two traps would be around 256,000 marvaledís. At that time, a skilled tradesman would be paid around 135 marvaledís a year. There would be around 300 people involved in the fishing at each site, and there was another disquieting aspect of this arrangement; if the nets remained empty (and sometimes they did) nobody got paid.

It became clear to Guzmán that somebody was making a lot of money out of the almadrabas. He knew how much the traders bought the tuna for, but now he wanted to know how much they were selling it for. The Order of Calatrava was riddled with corruption and the traders had taken advantage of this. But Guzmán had many contacts in the Cortez and knew where they were selling. The Calatravans had no authority over the lands that they had been given custody over, but Guzmán did. He could have traders, mayors or corrupt officials thrown into prison, or worse.

At the end of that first year, Guzmán presented the taxes that he had collected to King Ferdinand and his mother, Maria de Molina. They were ecstatic. They had the means to fund the army of Castile that would enable them to override the many powerful families and their private armies. They immediately gave him the trap of Zahara de los Atunes, and he now had control over the three most lucrative almadrabas in Iberia. I don’t doubt that Alonso had made a tidy profit for himself, but in the long run, he had opened up the lawless wilderness of south-western Iberia to settlers and farmers.

His next move was to build a secure storage compound for all the almadraba boats, nets and equipment that he owned. He chose to do this at Zahara de los Atunes where a decade earlier he had welcomed Emir Abu Yusef Yaqub in the ill-fated attempt to stop Sancho taking the crown. The fortified compound faces the beach and allows the boats, nets and all sundry equipment needed for the almadrabas to be brought within the walls. Now known as the Palace of Jadraza, it is mostly in disrepair. His other major construction was in the town of Conil, where he built a castle which had a watch-tower or Atalaya to connect him by line of sight to the other manned outposts of Roche and all the way to Chiclana.

The Palace of Jadjara at Zahara de los Atunes.

A drawing of the castle at Conil (in red) and the boats and nets of the almadraba. On the left is the tower of Guzmán

The story of the Duke of the Almadrabas does not end here. Each spring when the almadrabas began, the Guzmán family drove down to Conil and set up camp. They could have sailed down river from Seville, but they chose to go by road in a caravan of beautifully painted covered wagons with all the furniture and finery that a duke should have. They took up residence in the castle at Conil, but would drive down to the beach away from the smell and the flies of the almadraba, and his young family and wife could play and swim in the sea. Guzmán himself often joined in with the other fishermen as they pulled the tuna out of the surf. This tradition was passed down through the Guzmán family, and three hundred years later, a poor writer called Miguel de Cervantes wrote that he was going to Conil to “buy tuna and see the duke.”

With law and order restored, farmers began returning in droves to work the fertile land. Guzmán gained more in taxes as the villages grew, and he put this money into improving the roads. He ensured that he employed local labour for all his developments, with the result that the hand-to-mouth existence of the villages became more stable. Alonso Péres de Guzmán had proved that he was worthy of the title “El Bueno” and this should be a happy ending.

But the Marinids still held Gibraltar and Algeciras, and for their own safety, the Christian kingdoms wanted the threat of invasion that they posed removed forever. Guzman was now one of Iberian Christendom’s top generals, and before long he was drawn into his final campaign.

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (0)

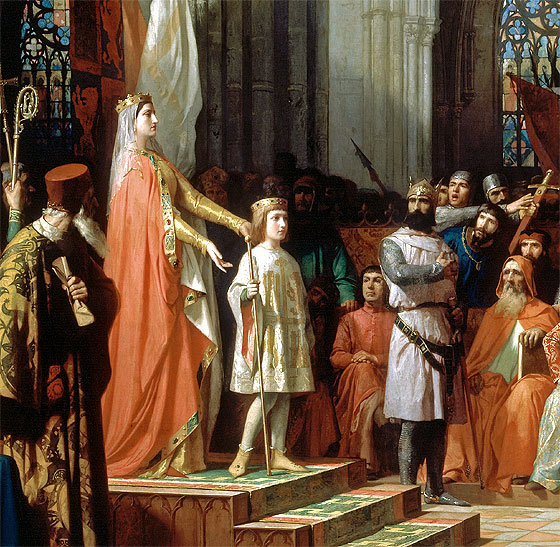

The lioness mother

Saturday, November 14, 2020

King Sancho IV died of tuberculosis in April 1295 leaving a widow and seven children. Thanks to his father, King Alfonso X, Sancho had been excommunicated from the Catholic Church. This meant that his children were considered illegitimate and ineligible for the crown. There were two other eligible contenders.

The first was Sancho’s nephew, Ferdinand de la Cerda, who had been chosen by King Alfonso X to succeed him instead of Sancho. He was living with Sancho’s mother in Aragon. The alternative was John, the Traitor of Tarifa. Both of these had a substantial number of followers amongst the nobles of Castile and León, making the potential for another civil war enormous.

Maria de Molina, Sancho’s widow, sent for Guzmán El Bueno (King Sancho gave Guzmán the agnomen “El Bueno” after Tarifa) to come to Alcala de Heneres to help her rule. Sancho had designated Maria as regent in the event of his death. Her first priority was the Church. She began petitioning the bishops and archbishops to ask the pope for an annulment of the excommunication order against her children. Guzmán, she sent out to rally the noble families around her cause.

John of Tarifa had moved quickly and already established himself as King of León, which had split from Castile as a separate kingdom. Maria’s oldest son, Ferdinand, was ten when his father died, and if she could have the excommunication lifted then he had a good chance of becoming king. The two biggest and most powerful families, Haro and Lara, were clawing for a bigger share of the power, but clever, patient Maria held them all at bay.

Maria de Molina presenting her son Fernando at the Cortez. Painting by Antonio Gisbert.

Maria was trying to keep John at arm’s length; she knew how dangerous he could be. He had brought her kingdom to the brink of war with Asturias shortly after she became regent of Castile. Apart from the brotherhoods or hermanadades that the nobles had created to protect themselves from rogue kings and coups, there were other orders that were often operating outside the control of the king.The Order of the Temple of Solomon, or the Templers, reached a level of freedom from accountability that is only matched in modern times by the likes of Amazon or Facebook. All of them were given special powers by the Vatican, and a mere kingdom had little power to influence them. However, all the orders were led by men, and they could be influenced.

Rue Perez Ponce de León was Grand Master of the Templers until his death in 1291 when the order elected his nephew, Pedro Ponce de León to succeed him. Pedro became one of the richest of the noblese after the death of his father. Together with his brother, Fernando, who was chancellor to Maria and Prince Fernando, they had control over vast areas and huge amounts of money. In 1292 they collected 75,720 Maravadís as tribute payments, as well as the right to collect taxes for parts of Extremadura controlled by León. At the same time, Pedro was collecting taxes from his father’s estates in Asturias and Galicia, rents from salinas along the coast and rents from the Jewish ghettos of Córdoba. He was also majordomo to the prince, and a rising star in the kingdoms. He had not gone unnoticed by John.

John involved Pedro in a secret deal with the King of Asturias to gain political favour in the court of Maria de Molina. For this he would receive a bribe of land and the rent from two towns. Before long, Pedro realised that he was becoming involved in something treasonable and told John that he wanted nothing more to do with the deal. John immediately changed tack and told Pedro that unless he complied he would tell Maria of Pedro´s attempt to involve him in the treasonous deals he had been committing.

For a week Pedro suffered in anguish before confessing all to Maria and Fernando. Fernando was furious and ordered John arrested and executed. Worse was to follow. The King of Asturias demanded the return of the land titles that he had used as a bribe or he would invade Castile. Fernando was like his father and would have gone to war, but his mother managed to dissuade him. This is when John´s 80 year-old mother arrived at court with the title deeds which she offered to give to Maria in exchange for pardoning her son. Evil John walked free.

At long last, the pope lifted the excommunication of Sancho, and in 1301, Sancho’s son was crowned King Ferdinand IV of Castile and a reunited León. All the others, including John of Rate, had to acknowledge him as king and abandon their claim to the kingdom. The next biggest prize in the kingdom was Lord of Biscay, and with the crown settled, greedy eyes focused here. Diego López V de Haro, “the intrusive” still held the title, but John of Rate considered that he had a greater claim. He petitioned Maria de Molina and the king to have him reinstated. Diego López V de Haro became so worried by John’s obvious attempt to undermine him that when John appeared uninvited at one of the king’s meetings in Guadalajara, Diego López arrived with an army to surrounded the town and demanded to see the king and his regent. An angry King Ferdinand would not allow him into the town and he ordered John to leave, too. Finally, in 1307, by petitioning the pope, John was able to go above the king’s head and have legal claim to the title, but only on Diego’s death. Even then, wily Maria managed to prevent John becoming Lord of Biscay, and it was his wife who took the title of Lady of Biscay and became head of the House of Haro.

Within the kingdoms, the only standing armies were those of the religious Orders. If a king wanted to fight a war against another kingdom he must ask his loyal nobles to provide troops and the provisions to feed them during a campaign. If he was lucky, there might be enough booty to pay everybody. (Booty was usually captured land and the taxes from towns. Added to this would be all of the livestock of these poor people. The land and taxes could then be divided up amongst the victors.) As the kingdoms grew and amalgamated this kind of funding for an army became impracticable.

Through the Cortez, Maria de Molina and her son lobbied to tax the rich landowners to pay a tax for a trained and equipped standing army. King Alfonso X had done the same in 1270 by creating the Order of Santa Maria, which was the nearest thing to a royal navy. Funded and controlled by a mix of clerics and nobles, they were specialists in naval warfare and instrumental in several major battles to control the straits between Africa and Iberia. The order had ships stationed in San Sebastián, La Coruña, and El Puerto de Santa María, but the main port and command centre was at Cartagena.

Maria and King Ferdinand also had to deal with The Order of Calatrava. The order took its name from the Arabic name for a castle in al-Andaluz which was captured from the Moors in 1147. The Templars were the original custodians, but were unable to hold the castle. Abbot Ramond of the nearby Cistercian monastery of Fitero offered to take on its defence. Shortly after, Father Diego Velázquez, a simple monk in the monastery, but who had once been a knight, had the bright idea of employing the lay brothers of the abbey to defend Calatrava. Lay brothers were the labourers of the monastery who were not in Holy orders and were employed for manual trades such as those of tending herds, construction, farm labour or husbandry. Diego recommended that they become soldiers of the Cross. Thus a new order was created in 1157. I am sure that the lay brothers were eternally grateful to Father Diego.

Over the intervening 40 years, the order of Calatrava had developed into a potent force in the Cortez and had developed abundant resources of men and wealth, with lands and castles scattered along the borders of Castile. It exercised feudal lordship over thousands of peasants and vassals and could field 1200 to 2000 knights; a considerable force in the Middle Ages. Moreover, it enjoyed autonomy and acknowledged only clerical superiors, with the pope as final arbiter. The order gained a big slice of its revenue from an annual fishing event on the west coast, and Maria decided to tap into this income, but she needed somebody she could trust who had the strength and courage to take on the powerful order. She turned to the man who had stood by her and her husband for decades, and whose loyalty was beyond question. Alonso Pérez de Guzmán.

2

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (5)

2

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (5)

The hardest decision a man could face.

Saturday, November 7, 2020

When King Sancho eliminated the main opposition to his rule, he threw his nefarious brother, John, into jail. When the killing was over, and he had made some changes, he released him again. While John was in prison, the king and his relatives executed a power-play that ensured that John was left out in the cold.

John had allied himself with Lope Díaz III de Haro, the Lord of Biscay, a lifelong enemy of King Alfonso X, and also Sancho. Sancho had executed Lope and all his followers after his accession to the throne. John was next in line to be the Lord of Biscay, but whilst John was in prison, he was unable to claim the title. Instead, Lope’s brother, Diego López V de Haro, who had been a supporter of Sancho, stepped in to take the title. Diego was ever after known as “the intrusive” for grabbing the title, but Sancho had planned the whole thing.

John was understandably furious. Without title, and his brother watching him like a hawk, John bided his time, but soon began plotting again. When Sancho discovered his renewed duplicity, John fled to Portugal, where he resumed his scheming. King Dennis of Portugal decided that John was too dangerous to have around, and threw him out of his country.

We will come back to John in a minute.

When Sancho’s elder brother died at Écija, and with his father in France, he instantly became de-facto commander of the entire Castilian army. The dates are muddled, but Sancho must have been around 20 years-old at the time. True, he had generals who were veterans of warfare, but it was his fighting spirit that impressed them and his troops. Fighting with Sancho around Córdoba during the Marinid invasion was another young warrior who was just as courageous as he was, and perhaps a little cleverer.

The origins of Alonso Pérez de Guzmán are obscured by the re-writing of history during the intervening centuries, and the deliberate erasure of the truth by his family prior to the inquisition. In an interview by Bettany Hughes for the BBC programme, When the Moors Ruled in Europe, the then XXI Duchess of Medina Sidonia, a direct Guzmán descendent, showed a document dated 1288 that permitted Guzmán to trade in grain. In another document dated 1297, and signed by the king, Guzmán was described as a “vassalo,” which means that he was a Moor.

Guzmán was at the signing of the treaty with Emir Abu Yusef Yacub after the first Marinid invasion. Sancho was also there, but at the signing, Guzmán’s half-brother, Álvero, publicly denounced “to the four winds” that Guzmán was a bastard and a Moor. Shortly afterwards, Guzmán left Iberia and allied himself to the Moroccans.

When King Alfonso X sought the support of the emir to combine armies and take Córdoba from Sancho, it was Guzmán who acted as go-between. In gratitude, the dying king gave Alonso land and towns along the west coast of the now sparsely-populated al-Andalus. He also suggested that Alonso should marry Maria Coronel, the daughter of one of his nobles, but before anything could be arranged the king died. As soon as Sancho was crowned, Guzmán returned to Africa. He had been instrumental in aiding King Alfonso lead an army against him, and he thought it best to move to Marinid lands where he was still in favour.

Sancho had grown up with Alonso as a friend, and he wanted him to return to Castile. He sent a message saying that he would honour the marriage to Maria Coronel. This would give Guzmán land and title in the middle of the Cerda stronghold that had supported his father. It would also put him and his possessions on the front line of any invasions by the Marinids. Sancho had inherited some of his father’s wisdom, and he realised that with a foot in both camps, Alonso could be a huge asset to his kingdom. In 1282 Alonso returned to Seville and married 16 year-old Maria.

For a while, he played an impossible double role. When Abu invaded Nazrid lands, Alonso fought with him, and he also led armies against Abu’s enemies in the Rif. But in Castile, he was one of the king’s trusted noblemen. When Abu Yusef died, his son became emir, and Alonso’s fortunes changed for the worse. Abu Yacub hated Christians, but he hated Alonso more, and when Alonso discovered that Abu Yacub was planning to kill him, he fled across the straits to Seville.

Guzmán helped Sancho strengthen the south west of Iberia against Marinid attacks and he fought with Sancho to take Tarifa in 1293. According to the treaty, Sancho was supposed to return Tarifa to the Nazrids, but the Marinids still had Algeciras, which was a staging post for invasions. He reneged on the deal with Muhammad and kept Tarifa, with a longer-term plan to take Algeciras, too, and stop Abu from crossing the straits for good. The problem now was finding somebody to take stewardship of Rate Castle at Tarifa. It was a very dangerous posting with Algeciras just along the coast, but from Tarifa's port, Christian fighting ships could control the straits. Guzmán volunteered, and King Sancho personally brought supplies and arms to Tarifa to back up his most trusted general.

This is where John reappears. Knowing of Abu’s hatred of Alonso, he left Portugal and crossed the straits to Africa, where he convinced Abu that he could take Rate Castle from Guzmán. He was going to use a tactic that he had used when he was fighting for his father at the siege of Zamora. He had captured the son of the woman who held the castle there and he threatened to kill the boy if she did not surrender. In those times, it was usual for noble families to have children brought up with other noble families; a way of cementing alliances. The chroniclers say that this is how John came to have young Pedro. It seems unlikely, given his time in prison and being thrown out of Portugal, but by some means John held Guzmán’s second oldest son as hostage. On the strength of this, Abu shipped 5,000 of his cavalry across the straits and added troops from Algeciras, and with this small army under his command, John laid siege to Rate Castle.

The west gate of Rate Castle, Tarifa. The west gate of Rate Castle, Tarifa.

Over the centuries this story has been written and re-written and the facts are muddled. Books and plays have been written about it, and it has become a legend in Spanish history.

Guzmán had learned of John’s plans and sent messengers to King Sancho. Sancho’s navy was at that time on the east coast of Iberia and would take weeks to arrive to give support, but what ships he had available he sent downriver form Seville and Huelva laden with troops. Alonso had also sent word to Vejer de la Frontera for backup troops to attack John’s northern flank. But regardless of troops and displacements, the battle would be decided when John brought out Guzmán’s son.

The siege went on until reinforcements from Sancho were attacking John´s troops from the rear, and the Castilian ships had been sighted on the horizon. That was when John dragged out the eight-year old son of Guzmán. John demanded that he surrender the castle or see his son killed before the gates. We cannot imagine the pressures and aguish that Alonso and his family felt, but Alonso stood on the battlements and refused to surrender the castle.

Guzman painted by Martinez Cublles Guzman painted by Martinez Cublles

There are several versions of the speech that Guzmán supposedly gave that day, but they all follow the same theme.

“Here is my knife, use it to kill him with. No son of mine would dishonour me, and his death will bring honour upon him and shame on you.”

Alonso drew his own dagger and threw it down to John. In fury, John cut Pedro’s throat and carried on hacking until he had severed the boy’s head. One chronicler writes that he put Pedro’s head into a siege catapult and fired it over the walls.

With his plan in tatters, John retreated to Algeciras and Abu Yacub withdrew his cavalry to Africa. Guzmán and his devastated family returned to Seville, where they stayed in mourning for several weeks. King Sancho had tuberculosis, and his health was deteriorating. He could not travel, so he sent a letter to Alonso asking him to bring his family to his palace at Alcalá de Heneres. The letter was full of praise, and likened Guzmán to Abraham. Alonso set off in his carriage from Seville, but when he arrived at the gates, all the noble families of the city had lined the road north. They fell in behind Guzmán’s coach and followed him. At each town they passed through, more people joined the procession. When they reached Córdoba, the nobles of the city, led by the mayor, met him outside the walls, and he and his family were welcomed as royalty. By the time they reached Alcalá de Heneres, the train of supporters numbered nearly a thousand, and it was swelled by nobles and villagers who had come from neighbouring towns. King Sancho addressed them all from a balcony above the palace plaza.

“Behold your model, no man can show more love for his country than to give his own son. Whilst Castile has men like this, we will never be defeated.”

Most of the tales about Guzmán end at Rate Castle, but there is much more to the Guzmán story. Guzman himself became very rich, and his descendants became the first Dukes of Medinia Sidonia.

When Francis Drake sailed into the harbour at Cádiz and “Singed the King of Spain’s beard” it was another Alonso Péres de Guzmán who chased him out. The same man later led King Phillip’s Armada fleet for the planned invasion of England in 1588.

Perhaps the least known of the Guzman line was a daughter of the Queen of Portugal, Donaña Louisa de Guisamo, whose fourth child became Catherine of Braganza, the wife of Charles II, and Queen of England.

Meanwhile, John had returned to Castile and continued his plotting with the disaffected nobles. He had by no means given up on being royalty. He had a lot to overcome, least of all his new title of “The Traitor of Tarifa.”

For the full story of Guzmán el Bueno I can recommend this book.

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08LHJGW49

The Path to Nobility is a gripping historical novel telling of Guzmán el Bueno´s rise not only through the courts of Christian kings, but his career fighting for Emir Abu Yusef Yaqub in Fez. The story begins with his birth as the illegitimate son of a nobleman in the court of King Alfonso X, and his youth during the Mudejar uprising. Whilst still a young boy, he fights in the streets of Toledo against the king´s cruel rule and joins the exodus of Moors trekking south when King Alfonso expels them from Castile. He is forced to leave his mother and return to the King´s court where he distinguishes himself in battle before defecting to join the Berber Emir of Morocco. He finally becomes one of the richest and most trusted nobles in Castile.

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (1)

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (1)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|