Galicia’s countryside is a land of smallholders whose farms may be small, but whose farmhouses are large. Many still contain the horreró, a store for grains and maize, like a small chapel standing on stilts sometimes crowned with a cross. Manuel Rivas, a poet and novelist who writes in Galego once calculated that there were a million Galician cows – one for every three inhabitants. Mad cow disease coupled with reduced EU milk quotas have reduced that number, but the early twentieth-century politician, Daniel Castelaeo, stated that the cow, the fish and the tree are Galicia’s holy trinity.

It is here between the Atlantic and the mountains that the vineyards are for the Rias Biaxas white wines are. Fermented from the indigenous Albariño grape, the local climate is perfect for the variety and produces wines that are equal to those of the Loire and Rhine valleys. But the future of the northern regions is uncertain. Castilla, Galicia and León have more than 3,000 abandoned villages. The owners of the land have disappeared and records of ownership, which would have been patchy at best, are now gone forever. The old have moved to the towns to be nearer to hospitals and their children. The infrastructure of roads and transport that would have served the isolated villages is gone, and many of the roads are impassable. The ancient forests that once covered this land have returned to claim their long-denied heritage.

The west coast of Galicia from Vigo to Coruña is indented with sea lochs or rias which are ideal places to harvest the many varieties of shellfish which grow in the nutrient rich Atlantic waters. It’s here that gangs of women wearing gum-boots and carrying buckets comb the sand and rocks at low-tide collecting winkles, clams, cockles, scallops razor clams and oysters. Their families build the neat rows of bateas, trellisworks of timbers from which hang ropes that mussels cling to by their hundreds. Hanging from the rocky cliffs on the sides of the long rias are the much-prized goose barnacles, or percebes which cling like bunches of purple claws. They are collected by the percebeiros, men who risk life and limb to scale the cliffs and scrape them off the rock. Costal Gallagoes have always been fishermen, and they still are, but now their trawler fleets range the Atlantic from Argentina to Angola in their constant search to find enough fish for a fish-hungry nation. They trawl seas that others have given up as too dangerous, with the result that around 20 Galician fishermen are lost each year.

Cape Finisterre is probably only known to people who listen to the shipping forecast. It’s not the most-western point in Europe, that claim to fame goes to Cabo da Roca in Portugal, 450km. further south, but according to the Romans, it was the end of the known world. The oldest working Roman lighthouse is still lighting the way for ships at La Coruña. The Torre de Hercules was built in the second century and reformed in the eighteenth century. But Finisterre is a place that ancient sailors dreaded.

There is safe haven at La Coruña and at the naval shipyard and military base of El Ferrol del Caudillo, (Temporarily so named because it’s the birthplace of Franco) but for the many ships that turn east into the Bay of Biscay or south into the Atlantic at this very busy corner there is very real danger. The weather is notoriously unpredictable, and the rocky coast faces the full force of Atlantic storms. Any ship unlucky enough to make a navigational mistake or run into difficulties on this coast has little chance of rescue or assistance. North of Cape Finisterre the coast turns east and gains the grim name of Costa da Morte, the Coast of Death. A local historian, José Baña, has recorded some 200 shipwrecks and more than 3,000 dead between 1870 and 1987. The Royal Navy training ship, Serpent, with 170 boy sailors on board ran into a violent storm here in 1890, and all were lost except three of the boys. The only reminder of the tragedy is a lonely walled graveyard called the Cemetario de Los Ingleses on the cliffs above the rocks where they died. All along this coast are granite crosses to denote other ships lost within sight of land.

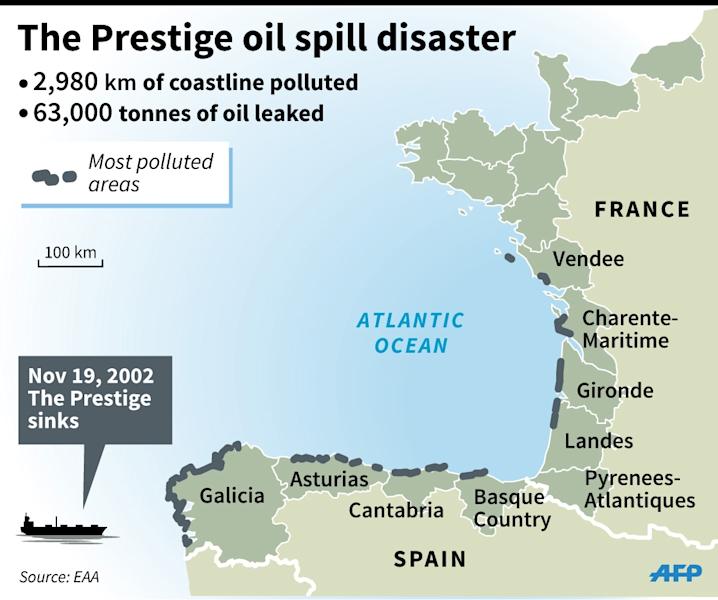

More than 40,000 merchant vessels round this point each year, 1,500 of which are oil tankers. Every decade or so one of the tankers gets into difficulties or goes aground, releasing its foul cargo into the sea to be smeared across Galicia’s coastline. Three of the world’s worst 20 tanker disasters happened here. The Urkuiola spilt 100,000 tons of crude oil in 1976; the Aegean Sea was forced onto the rocks beneath the Roman lighthouse at La Coruña in 1992 releasing 74,000 tons of oil. Then in 2002, the Prestige carrying 77,000 tons of heavy fuel oil broke its keel in a storm on the night of 13 November, and the people of the tiny coastal village of Muxia woke up to find the crippled tanker on their doorstep.

Rescue tugs arrived and got lines to the tanker and the crew were taken off. Meanwhile, the Juntas of Portugal, Asturias, and Cantabria were screaming at the tugs and each other over where to tow the crippled ship; none of them wanted oil on their beaches. Eventually they all agreed to tow the ship into the Atlantic far from their coasts and then south so that any oil spill would go to Africa. Their cynical logic being that the third world would lose nothing of value if its coastline and wildlife was destroyed by the foul black oil. Alas, it was not to be, 130 miles off Finisterre the Prestige broke in two and sank. The heavy fuel oil was supposed to solidify at low temperatures, and that is what the government had told everybody. It didn’t, and most of the oil ended on the beaches of the Costa da Mort.

The damage to the ecology of the Costa da Morte was horrific. Coastal fishing was impossible and the thick oil covered the bateas and killed the mussels. The beaches were covered killing the native molluscs. Seabirds unlucky enough to land in the oil floated lifeless on the black tide and were washed up along the coast in their thousands. The government sent in the army, but took its time in arriving in person. Meanwhile, the television coverage of the carnage enraged the population of Galicia, and indeed the rest of Spain. Coachloads of volunteers turned up to clean up the mess, and the government donated masks and white overalls. Their fury at the scale of the damage to the coast erupted into a national protest with the slogan Nunca Mais, Never again!

The master of the Prestige, Captain Mangouras, was arrested on a charge that he did not comply with the Spanish request to re-start his engines and move away into the Atlantic, making sinking inevitable. He wanted to bring his ship into port and surround it with an anti-spill boom which would have contained the oil. The Prestige had set sail from St. Petersburg, Russia, and her previous captain, Esfraitos Kostazos, had resigned in protest at the poor state of the ship. The two sister-ships to the Prestige had been condemned for metal fatigue in their centre sections and scrapped. After the ensuing court case, Captain Mangouras was imprisoned for two years, and Spain was granted 1.5 billion euros in compensation. To commemorate the national effort to clean up the oil-spill and to re-affirm the call of Nunca Mais, a monument was erected on the headland within sight of the sanctuary of A Barca. The Prestige now lies at a depth of 3,000 meters, 30 miles from the coast and as of August 2003, the tonnage of oil released stands at 63,000 tons; 80% of the Prestige’s cargo. The remainder is still in her tanks.

A memorial sculpture was erected close to the church to commemorate the huge effort by ordinary Spanish people to clean up the oil-spill and remind people that this must never be allowed to happen again.

There is a more sinister and terrible aspect of this part of Galicia that is perhaps worse than oil-spills and it owes its origins to the thousands of emigrants who left Galicia for South America. The coastline of Galicia is perfect for smuggling, and until the 1980’s this was a harmless trade, even a little romantic. For the most part, the Civil Guard looked the other way as tobacco, alcohol and sometimes even white goods and televisions would be unloaded from trawlers or merchant shipping offshore onto smaller, faster boats, which landed the goods on the many isolated beaches of the rias.

This changed when the Colombian cocaine cartels made use of the family connections between Galicians who lived in Colombia and their relatives who still lived in Galicia. The network was already there; it just needed beefing up with some heavy muscle and big money. Typically, two men would book into a hotel in one of the port towns like Villagarcia along the coast. They would share the same room, but that was not because they were gay; one was an armed bodyguard for the other. They bought large houses in the country and fast boats which they moored in the harbour. New businesses would appear which never seemed to have clients, and the fast boats only went out to sea at night. The drug wars to establish routes, links and corrupt officials, which were common in Colombia, began to seep into the Galician cities. The bodies of young men with gunshot wounds began to appear on the streets. Soon the cartels became known and infamous; the Charlines, the Oubiñas, Prado Bugallo, and Sito Miñanco. The cartel bosses rarely put in an appearance, and the drugs arrive by a tortuous route that is difficult to unravel, let alone prove in court. Somewhere off Cape Verde, the drugs are offloaded from merchant vessels or private yachts and transferred to trawlers which have no discernable routes or destinations. The trawlers eventually pass close to the Galician coast and are met by high-speed inflatable RIBs driven by Galician planeadoras, who take the drugs to isolated beaches where they are picked up and taken by road to secure houses in the campo. The drugs are left there for Colombian distributers to pick up. It is they who have arranged devious overland transport to cities all across Europe where they distribute it to their dealers. In just two decades, they have made Galicia the main gateway for cocaine to enter Europe.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, Galicia, and to a lesser extent the rest of Spain, tied with Mexico in the league tables of sheer tonnage of cocaine captured by the police each year. Only the United States and Colombia consistently beat them. Every year more than 44,000 kilos of cocaine are seized, which at around 40 euros a gram (2006 prices), adds up to 1.76 billion euros. The Spanish police are only too well aware that this represents about half of the total traffic, with at least as much again reaching the streets of Europe. The Galician cut, as facilitators in this trade, is around 25%, giving the local economy something like 660 million euros bonus annually. As one Spanish customs official explained to the press: “We are not the tip of the iceberg as we once thought. We are the iceberg!” The Spanish are Europe’s biggest cocaine consumers along with the British, with one in fifty admitting to have used cocaine recently. Meanwhile, cocaine accounts for half of the victims in the drugs related death-rate league tables for both counties.

Much of the above was taken from The Ghosts of Spain by Giles Tremlet. The rest was from Wikipedia.