Chris Reed commented in a previous blog about the significance of hand positions in religious art. I didn't find anything much about hand positions, but I did find this.

When we talked about the Islamic conquest of Spain we dealt mostly with battles, but it was not all war, and we often forget the other things that were established or changed during this period. Just to give you some idea of where we are starting this story, we must go back to a period of turmoil in Spain’s history. Around the year 995, Sancho Garcia, was heavily embroiled in a conflict with his father, Count García Fernández, which led to the partition of Castile. As was typical of the times, he had allied himself with Al-Mansur of Córdoba in order to take his father’s title. He didn’t get the title then, but had to wait until his father died five years later. He illustrated the untrustworthiness of Christian kings by immediately renewing the Reconquista and turned against his ally Al-Mansur. He was defeated at the Battle of Cervera in July 1000. By September the same year, he had to fight against a, not unreasonable, Córdoban invasion of his county. Al-Mansur died in 1002, leaving the Caliphate of Córdoba in crisis, but this meant that the caliphate was no longer a threat to Castile. Sancho was now left with nobody to fall out with, so he turned on his own family and started trouble there. Castile was not at peace again until Count Sancho Garcia died in 1017.

However, King Sancho did do one good thing during his life that would be of benefit to mankind, even though it was unintentional. For his daughter, Tigridia, he founded the San Salvador Monastery in Oña. It was a double monastery combining a convent and a monastery. The nuns came from the convent of the Monastery of San Juan in Cillaperlata, while the monks were from the Monastery of San Salvador in Loberuela. The charter of the monastery lists a huge number of towns, churches, estates and other monasteries which Don Sancho granted to his foundation. Large portions of the present provinces of Burgos and Santander were placed under the jurisdiction of the monastery, and its wealth grew with the centuries as more and more kings and noblemen donated territories and extended privileges to it. Tigridia certainly benefited from her father’s benevolence; she became the abbess of the monastery and was canonized upon her death.

The Monastery of San Salvador: photo Spottinghistory.

In 1033, King Sancho III of Pamplona (a different Sancho) gave the monastery to the Abbey of Cluny, and it became part of the largest monastic group in the area. The group flourished during this period, later growing to have over 70 other monasteries and churches under its authority. This organisation continued for another 450 years throughout one of the most turbulent times in Spanish history. Personally, I can only applaud the nuns and monks who withdrew behind their monastic walls to live a life of peace whilst carnage, hatred and intolerance raged unchecked outside.

Aside from its material wealth, its library housed a very rich collection of classical and medieval manuscripts and was a centre of learning. In the fifteenth century, the reign of the Catholic monarchs, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile brought about decisive changes in Spain and altered life in the Monastery of Ofia. The monastery lost much of its autonomy and some privileges when it was brought under the control of the Spanish Benedictine Congregation, whose centralizing policy was favoured by Isabella and Ferdinand.

In 1506 the San Salvador monastery joined the Benedictine Congregation of Valladolid, which had begun a program to reform the monastic life and follow a strict interpretation of the Rule of Saint Benedict, which requires that the monks take a vow of silence. Silence plays a salient role in Benedictine life. It is thought that by clearing the mind of distraction, one may listen more attentively to God.

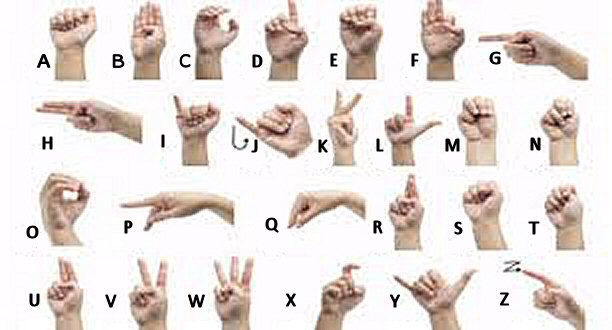

But a vow of silence brings difficulties when it comes to the day to day running of a monastery, and the monks overcame this problem by developing a series of hand signals which they had used and developed over the centuries. The Trappist rubric, (meaning instructions, or a guide) for “Living in silence", has illustrations of centuries-old hand gestures which were developed to “convey basic communication of work and spirit”.

The changes gave rise to an increased exchange with other Benedictine monasteries and resulted in the transfer of Fray Pedro Ponce from a monastery at Sahagfin, León, to the Monastery of Ofia. Although he was a member of an illustrious Spanish family, not very much is known of Pedro Ponce de León. He was born in the town of Sahagfin, and took his monastic vows in the Benedictine monastery of his home town on November 3rd, 1526. A contemporary describes him as a reserved, humble devout man, a keen observer who devoted much time to the study of nature, collecting herbs and investigating their uses. The Monastery of Ofia was thus an ideal place for such a person.

It was also an ideal place for the Marquis of Berlanga, Juan Ferndndez de Velasco, to keep his two deaf sons out of the sight of society. The Velasco family had been one of the wealthiest and most powerful families in Spain since the thirteenth century. One of its members, Don Bernardino de Velasco, who died in 1517, had been appointed by the Catholic monarchs first Condestable of Castile, i.e., Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces. That title became in time a hereditary and honorific one.

In those times, the deaf, dumb, mentally disabled, disturbed or insane were all grouped together. There was no science to differentiate them, and the church excluded them all because they were considered to be too subnormal to be educated. If they were incapable of learning the sacraments they were outside of the church and ineligible for salvation. Some even believed that they were possessed by evil spirits.

This is where Girolamo Cardano joins the story. Girolamo was born in 1501 in Pavia, Lombardy, and if his mother had had her way he would have been aborted before birth. His father was Fazio Cardano, a mathematically gifted jurist, lawyer and close personal friend of Leonardo da Vinci. His mother was Chiara Micheri, and when she learned that she was pregnant she took "various abortive medicines” to end the pregnancy. Girolamo was illegitimate, and just before his birth his mother had to flee from Milan to Pavia to escape the plague which had taken her three other children. I am not religious, but I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that his survival was a miracle.

Cardano grew to become a visionary thinker and published two encyclopaedias of natural science which contain a wide variety of inventions, facts, and occult superstitions. He is also credited with the invention of the Cardan suspension, or gimbal, which allows a ship’s compass to remain horizontal whatever the motion of the ship. But it is his comment on people who were deaf that is of interest to us. He wrote sometime around 1550 that "writing is associated with speech, and speech with thought, but written characters may be connected together without the intervention of sounds. The deaf can hear by reading, and speak by writing."

Significantly, in the history of education of the deaf, he said that deaf people were capable of using their minds, argued for the importance of teaching them, and was one of the first to state that deaf people could learn to read and write without learning how to speak first.

It is not known whether Pedro Ponce had read about Cardano’s theory, but what is recorded is that he gave lessons to Gaspard Burgos, a deaf man who had been refused membership of the Benedictine order because of his handicap. Under Ponce’s tutelage, Burgos learned to speak so that he could make his confession. It is not known if Pedro Ponce taught him the Benedictine hand signals, but it seems highly likely that such a ready-made method of communication would be used. Burgos went on to write a number of books, which unfortunately have been lost to time.

The Marquis of Berlanga heard about Pedro’s successes in teaching the deaf to read and write and he paid the friar to tutor his sons. They learned to read write and speak in a fashion, and were able to inherit the title of their father and join society again.

Statue of Fray Pedro Ponce de León in the monastery grounds.

Statue of Fray Pedro Ponce de León in the monastery grounds.

There are no drawings or documents in the archives to prove it, but Ponce is thought to have developed a manual alphabet which would allow a student who mastered it to spell out (letter by letter) any word. This alphabet was based, in whole or in part, on the simple hand gestures used by monks living in silence. He apparently traced letters and indicated pronunciation with lip movements to introduce and develop speech among his students. He first taught his pupils to write the names of objects and then to try to say them. Ponce de Leon's method proved that, although we learn first to speak and then to write, the reverse order worked for the deaf. This was a bold step for the times, and was not universally accepted. Pedro Ponce died in 1584, but the recognition for his pioneering work did not spread much further than the area around the monastery.

This is where Juan Pablo Bonet, another Spanish priest, joins the story. Bonet was born in in 1573 at Torres de Berrellén in Aragon, and he eventually became secretary to Juan Fernández de Velasco, 5th Duke of Frías, Condestable of Castile. The Duke’s second oldest son was deaf, and he had employed a tutor to teach him to read, write and use sign language. Bonet was intrigued and became friendly with the tutor who explained his teaching methods in detail.

Juan Pablo Bonet

Juan Pablo Bonet

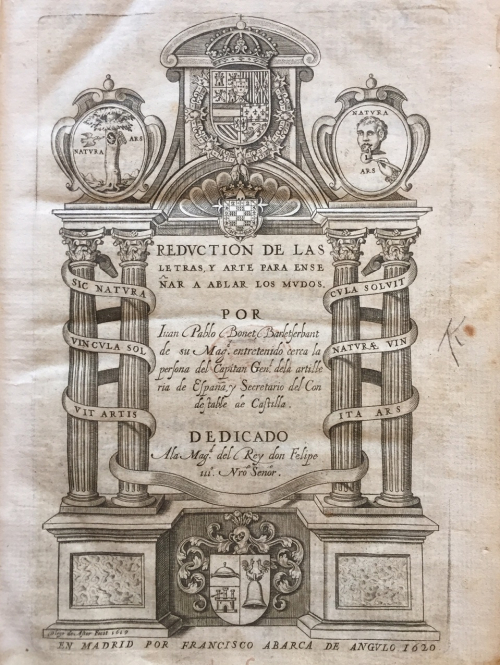

In 1620 Bonet published a treatise in Madrid entitled, "Reduccion de las Letras y arte para Enseñar a hablar los Mudos". He made use of a manual alphabet, invented a system of visible signs representing to the sight the sounds of words, and gave a description of the position of the vocal organs in the pronunciation of each letter. The book is considered the first modern treatise of phonetics. It also depicts the first documented manual alphabet for the purpose of deaf education. His intent was to further the oral and manual education of deaf people in Spain. Bonet's manual alphabet has influenced many sign languages, such as Spanish Sign Language, French Sign Language, and American Sign Language.

Bonet's publication.

Bonet's publication.

His work contains many valuable suggestions useful to modern teachers of articulation and lip-reading. He became a pioneer of education for the deaf, but many historians believe that he had been told of Pedro Ponce’s work, read his notes, and used much of the material in his treatise. He never credited Pedro Ponce de León for any of the information and exercises in his book, but really it doesn’t matter. The important thing is that he published the information to the world, which helped hundreds of thousands of deaf people to lead normal lives.