Last Supper: The Film

Saturday, February 27, 2021

The painter of our final Last Supper was born on 26 October 1935 in a small Italian village called Sant’Antonino just outside Treviso. Renato Casaro had a teacher in his local school who spotted his talent and encouraged it from an early age. The boy carried a notebook with him everywhere and made sketches and caricatures of the people that he saw. His mother frequently scolded him for making drawings in all of his schoolbooks instead of practicing his writing and arithmetic.

But Renato’s greatest passion was the cinema. He watched every new film that came to town, and usually its arrival was announced with a poster. When the film moved on to another town, Renato asked for the poster that had advertised it. He would rush home to get out his pencils and paints to copy it in his bedroom.

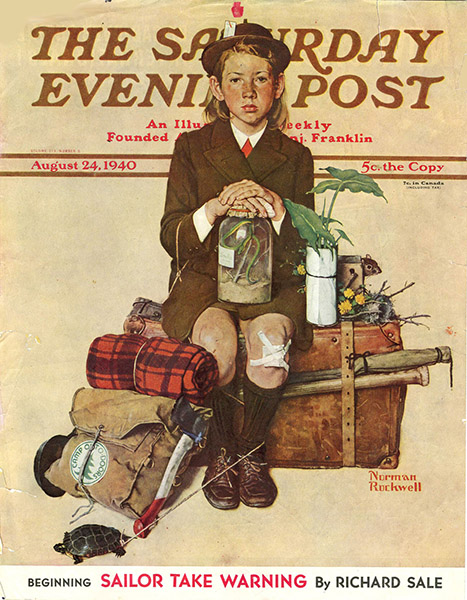

As well as the cenema posters, Renato had another treat which arrived once a week. Somebody in Treviso had ordered the Saturday Evening Post at the newsagent, and Renato eagerly awaited the day when the magazine arrived. Usually, the cover had been illustrated by Norman Rockwell, whose work he worshipped. He copied every piece of advertising artwork he saw, and as he grew and his talents developed, Renato realised that he had gone beyond the abilities of his schoolteachers to teach him and if he wanted to learn more he would have to leave Treviso and go to Rome.

He had become very proficient in technical drawing, and his father was a shipbuilder who understood the kind of drawings that engineers work with. He helped Renato hone his talents in that direction, and things would have gone differently if his father had anything to do with it. Renato could have easily found work at one of the big car plants that were appearing in post-war Italy. His parents wanted him to have a “normal” career despite his yearning for the cinema. A poor compromise was struck, and he went to work for a publicity agency that supplied advertising posters for local producers. His first commission was a painting of a panettone, a kind of Italian Christmas cake.

Each morning, on his way to work, he passed Cinema Garibaldi. The building had an outside wall on which were painted advertisements for the week’s coming film. Renato asked if he could have the job of painting the adverts, and after seeing his work, they told him to start immediately. This was more like it! Among some of his first paintings was Burt Lancaster in Apache, and Marilyn Monroe in River Without Return.

Renato faced his first crisis at the age of 20 when he told his family that he wanted to go to Rome and be a film poster artist. His mother was worried about him living alone in the big city, but he was adamant that this was what he wanted. He gathered all the photographs that he had taken of his cinema paintings and a portfolio of artwork and sent them to Studio Favalli, a famous design and art studio working for the Rome film industry. He was hired, and immediately left his family and set off to Rome. His new employers were pleasantly surprised to find that he was quick to complete projects that were given to him, and for this reason he was given the nickname ‘Renato fa presto’, which translates to ‘does quickly’.

There was a break when he had to do his compulsory 18 months national service, but the Air Force asked him to paint their recruitment posters and provided him with his own studio, so he painted for them during the day and carried on with film posters in the evening. His first big film poster commission came when he was only 25 and it was for The Magnificent Seven.

In 1966 he was asked by the Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis to paint the posters for The Bible and this was the first of a long list of posters that he produced for De Laurentiis.

Some of his artwork during this time include Waterloo, Flash Gordon, Dune, the German version of Dances With Wolves and Conan the Barbarian.

He established his Studio Casaro in Rome, and by the beginning of the 70’s he was taking on work from many different studios in Europe. Some of his older rivals were retiring, but Renato was still developing his techniques, and it was around this time that he began to use an airbrush for his artwork. He was singular in that he always had the say in how or what he painted for a poster, but the directors were always happy with the results. Renato was soon working on worldwide marketing campaigns for numerous films in America, Germany, the UK, France, Japan and many other countries.

One of his most memorable trips was to Tabernas in Almeria, Spain, for the Dino De Laurentiis production of Conan the Barbarian. It was around 1979 when he met Arnold Schwarzenegger on the set of Conan in Almeria at a time when no one knew who he was. He was famous in weight training circles, but all they knew him for was that he had this very impressive powerful body. Of course, nobody working on the film had any idea how famous he would eventually become. Renato was also shown around the Western area of the set at Tabernas and he was very impressed by the faithful reproduction of the set. It was like a piece of old America had been reconstructed in Spain. He had just missed the start of another superstar’s career which began at Tabernas in 1965 when Clint Eastwood filmed A Fistfull of Dollars there. Sandro Symeoni had painted the original Italian poster for the film, but Eastwood was an unknown at the time and he was badly painted in the poster. When the film was re-released in Germany at the end of the 1970s, Leone asked Renato to make sure this poster had a good likeness of Clint. However, Rene did paint the poster for Bad Man’s River starring Lee Van Cleef in 1971.

The light and ambience at Tabernas fascinated him and he promised himself that he would return someday. Unfortunately, the next few years saw him working seven days a week producing artwork. The Studio Casaro in Rome was working flat out now, but the long punishing hours that he worked took a toll on his marriage, and he and his wife decided to divorce.

After marrying his second wife, Gabriele, they moved to Munich for a while and worked for the German film industry. There was a dearth of good poster painters here during the 80’s, and for a while he had pick of the market. But times were changing, and he could see the end of his career as a film poster painter. Many of the new films were computer generated, and so were the posters. The last poster he did was for the film Asterix and Obelix vs Caesar in 1999.

That was when he started working on a new series of paintings depicting film stars, which he called Painted Movies. Renato explained, “It was a great feeling to be able to work on an image of these actors I admired without having the pressure of a delivery deadline. I was free to choose the way they were depicted, and I had a lot of fun doing it.” He decided that it was time to return to Spain. He had a house built in Málaga, and opened a studio and gallery at Puerto Banus. From then on, he and his wife decided to live and work in Spain.

It was no coincidence that he chose Puerto Banus to have his gallery. Sean Connery and many of the other film stars that he painted owned houses in the complex around the port, and some had their private yachts in the marina there, too. In the early years of Puerto Banus, the list of film stars who holidayed there was impressive. Ava Gardner, Grace Kelly, Audrey Hepburn, Cary Grant and Laurence Olivier, all visited the Marbella Club, making it the Costa del Sol's first luxury hotel. The prospects of selling his paintings here were obvious. Many of the Painted Movies are of films that he would have liked to work on, films that he saw as a young boy, or films that others painted the posters for. His main theme was cinema, and once he was free of production constraints he could let his imagination roam.

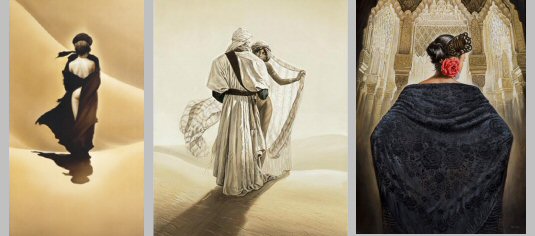

Renato has also painted a new range of pictures themed on the Islamic occupation of Andalucia, no doubt to woo some of the Saudi royal family who have built houses in Marbella.

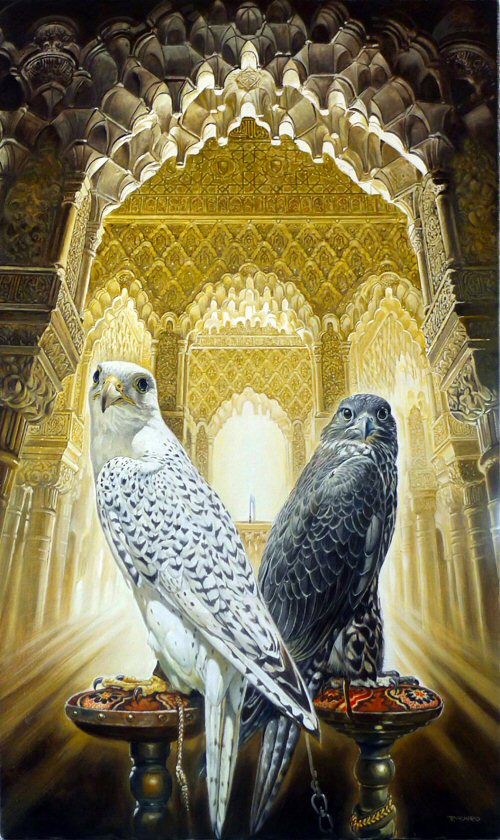

The Saudis are all keen falconers, and Renato painted a series of pictures for them. He has also begun a new series of wildlife paintings which are gaining in popularity.

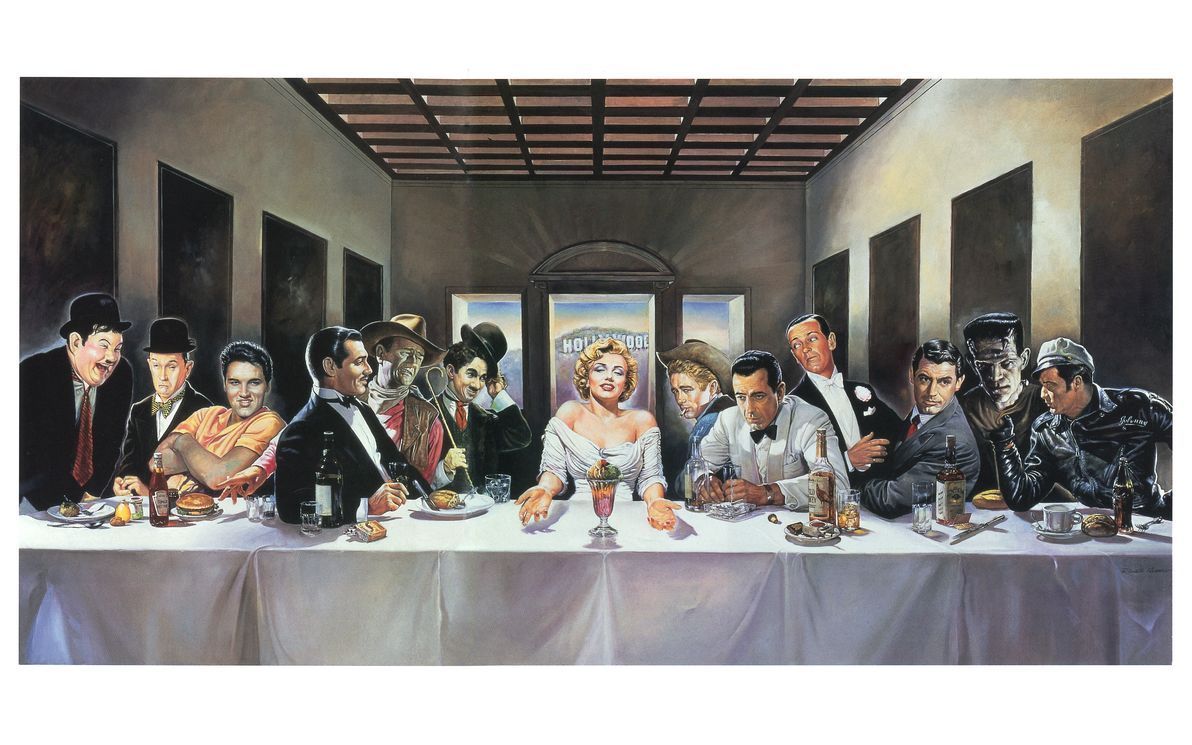

But it is his cinematic Last Supper in the style of Da Vinci that has set the tone for Renato’s light hearted look at Hollywood.

He follows up this with A Break in Filming, a parody of the famous photograph of steelworkers taking their break above New York.

When the lockdown is over, and we can move about again, why not visit Renato’s gallery in Marbella. For most of you guys it is just a couple of hours down the AP7. The address is on the internet. I never got to see it when I lived in Spain because I simply did not know about Renato, but when things are safer, I am going there.

I also want to visit Madrid again because I never got round to visiting the gallery of Joaquin Sorolla, one of Spain’s greatest painters (In my humble opinion). Also, I would like to visit Gaudi’s houses in Barcelona and see the Sagrada Familia again. In England, I am going to make the pilgrimage to see Giampietrino’s Last Supper in the Magdalen College, Oxford. For those of you who have moved to Spain, don’t waste the opportunity to see its amazing cultural heritage. In the wake of Coronavirus, promise me that you will go and see some of these Last Suppers.

0

Like

Published at 8:17 AM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 8:17 AM Comments (0)

From Coca Cola to the last supper!

Saturday, February 20, 2021

Joseph Harry Anderson was born on August 11, 1906. His family were devout Seventh-day Adventists and his father, Joseph, named all of his son’s Joseph, so each son went by his middle name, and this is the name that Harry used throughout his life. Harry had a sister and two brothers and all of them were outstanding students, with Harry excelling in mathematics.

His aim was to study maths at university, but in the interval between college and university Harry worked as a stock boy in large stationary store. When the store sign painter could not meet his deadlines Harry offered to stand in. His manager found Harry to be more than satisfactory, and he let him use a fourth floor room as a studio and he became the store’s permanent sign painter.

He enrolled at the University of Illinois in 1925, but when he came to register for his sophomore year he had to choose another subject. The maths course was hard work and Harry wanted something easy that would not overtax him. He chose a course in still life painting. After his first year in the art classes, his teacher, who was an alumnus of the Syracuse School of Art, asked him if he had considered art as a profession rather than mathematics. In the autumn of 1927, he began attending classes at Syracuse as a full-fledged art student with friend and fellow artist Tom Lovell.

The two attended classes together and shared a studio in the attic of Anderson’s dormitory. As well as working on course subjects, they earned extra money freelancing with Harry working on lettering jobs and Tom painting pulp covers. They both graduated with honours in 1931and moved to New York City to set up a studio in some old stables in McDougall’s Alley just off Washington Square. They had arrived in the illustration world in the middle of the depression and work was very hard to find. Harry served behind the counter for a sweets store in the evenings, and by day toured the agencies with his portfolio of artwork. Finally, after months of small jobs producing book jackets, he got his first commission from one of the big magazines, Collier’s.

With Collier’s under his belt was more confident about approaching the big publishers and agencies and began to earn enough to support himself with art alone. He quit the sweet store and paid off his debts, but he was tired of the rat-race in New York and began to save for his fare to return to Chicago where he knew the biggest prize was.

The Stevens-Gross Art Agency was the most successful art service agency in the Midwest, if not the entire country. They had a studio room where all their artists worked together and had models and photographers working along with the artists. Reps toured the country and brought in orders from advertisers and the top magazines in America. For providing this service, Stevens-Gross took 50% of sales, but Harry thrived on it.

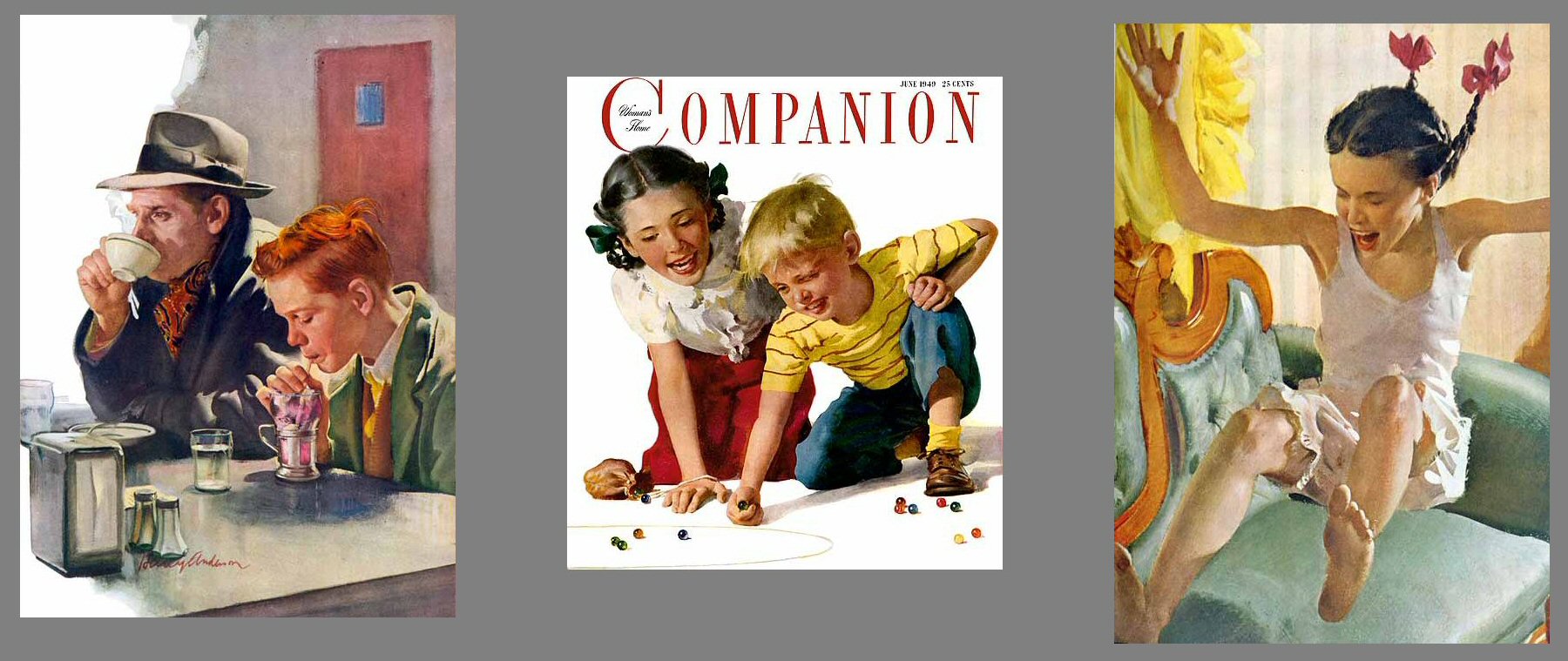

His first big assignment was a series of illustrations for a Cream of Wheat advertising campaign, produced in 1937. Big commissions began to come to him: American Airlines, Ovaltine and Ford all asked for Harry to paint their advertisements. By 1940 he was working for Collier’s, Redbook, The Saturday Evening Post, Woman’s Home Companion, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Cosmopolitan.

Cosmopolitan, Woman’s Home Companion, Cosmopolitan.

Esso, Coca Cola, Colliers.

It was whilst he was working for Stevens-Gross that he met a young woman called Ruth Huebel who was working as a model in the studio room. They dated for a while during 1940 and finally married. It is Ruth who modelled as the mother comforting her young daughter in the Collier’s painting above. Harry had kept his faith throughout the years and he and Ruth joined the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Harry was now very well established in his own right and could leave Stevens-Gross and work for the Haddon Sundblom studio. Shortly after this move he had a crisis of faith. He felt that, due to his religious beliefs, he could no longer continue to paint for some of the publishers or companies that he had been working for in the past. The decision would have a big impact on his income.

By 1944 Harry and Ruth had two boys and a daughter to look after, and were struggling financially. Because of his strong beliefs and his fame as an artist, Harry was approached by The Review and Herald Publishing Association to produce religious illustrations for them. Harry agreed, and his first commission for the church was to paint Jesus talking with children. He broke with the long traditions of the publishers to show Jesus in a modern setting rather than a biblical one. He painted Jesus in a garden with a young girl dressed in modern clothes sat on his knee. There are other modern children around him and the girl on his knee is asking about the crucifixion marks on his hand. Harry called the picture What happened to your hand? The painting caused a furore within the church, and the editor was urged not to print it because it was blasphemous. He was on the verge of returning Harry’s work when the editor’s daughter saw the picture and said that she wished she could sit on Jesus’ knee and hold his hand. That made up the editor’s mind. He printed the picture, and instead of the predicted disapproval, it was met with great acclaim. Harry continued with his modern theme and produced around 300 religious illustrations for the Review and Herald Publishing Association over the next 35 years. Eventually, this huge body of work comprised half of the total artistic output of Harry’s life. He continued to paint commercial art, but he split his time between that and work for the church. Throughout the rest of his career he charged only the minimum wage for his religious artwork.

In 1946, the Andersons moved to Washington. D.C. to be closer to The Review and Herald offices. He continued working for several of his old customers and in 1949 he painted covers for a whole year’s editions of Woman’s Home Companion. The theme for each cover was “brother and sister” and Harry’s own son was model for some of them, but Harry was beginning to feel a little isolated and missed the interaction with other illustrators that he had enjoyed over the years. Finally, in I951, the Andersons moved closer to the New York City area. During this period, Anderson began to receive awards from several of the associations that he had worked for, and he was featured in a 1956 issue of American Artist in recognition for his contribution to art.

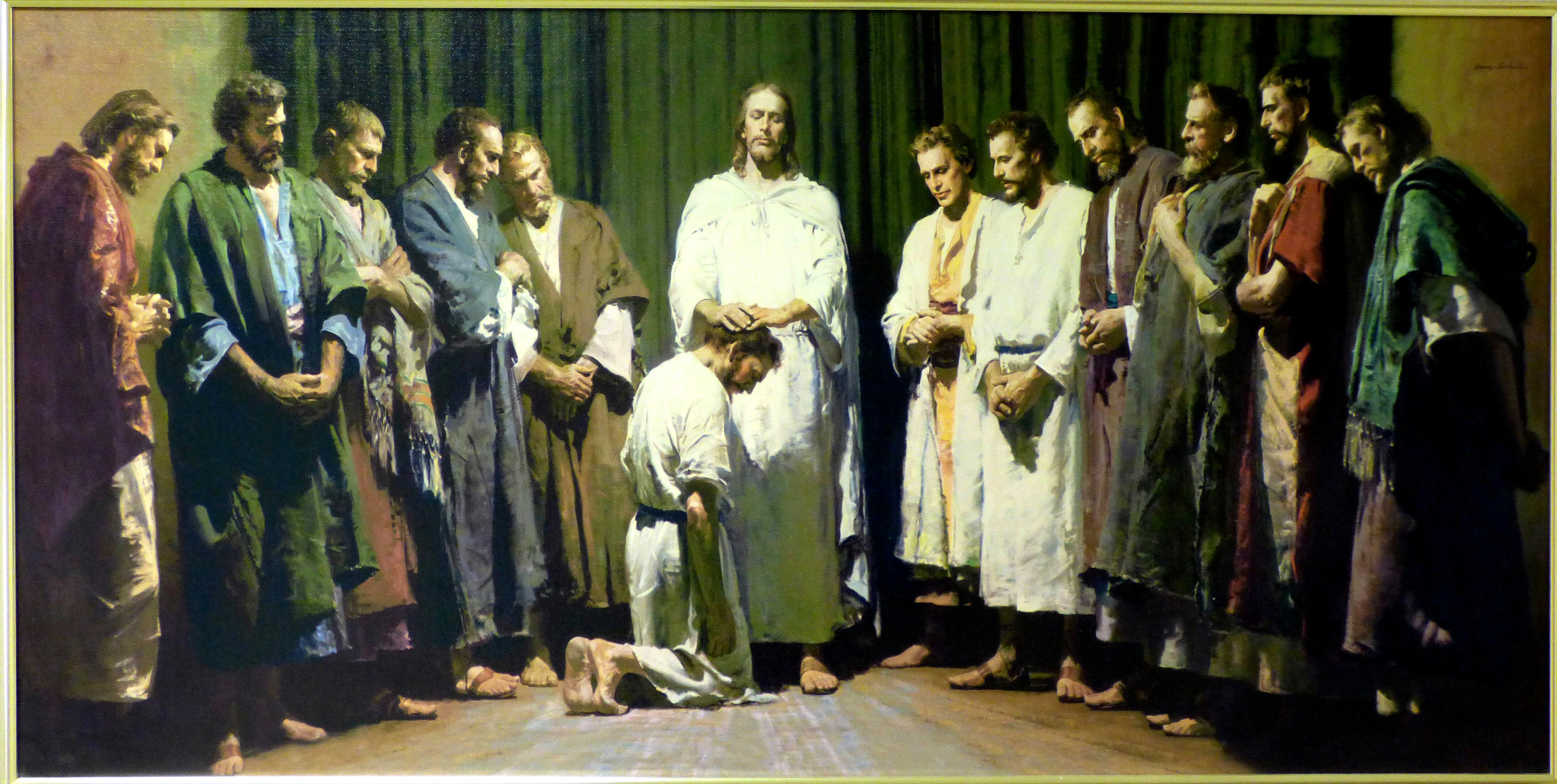

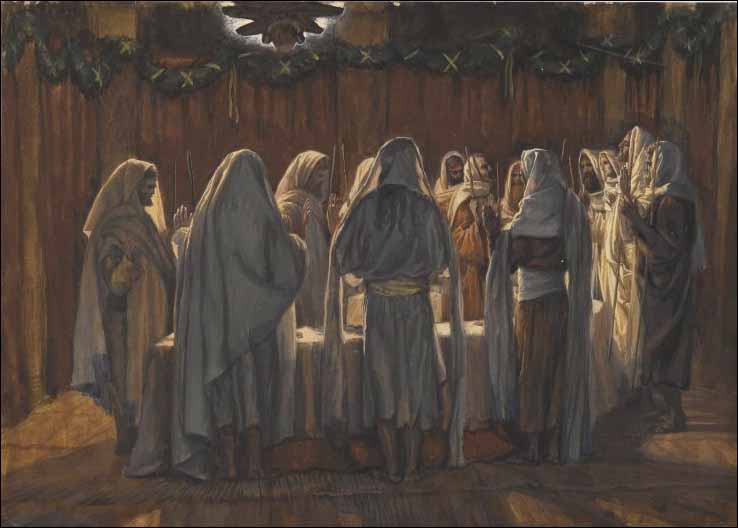

In the mid 60’s he was asked to paint a number of paintings for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. For the church’s pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair he painted a large mural in oils of Jesus ordaining his apostles. Re-prints of this painting can be found hanging in nearly every Latter-day Saints Church meetinghouse and temple in the world, following this, he did nearly two dozen more paintings for the LDS Church and his paintings are also still widely used by the church for many of its printed and online materials.

I have seen a large print of The Apostles close up, and I can verify the detail and accuracy of skin colours and the textures of the clothes. This is, to my mind, his crowning masterpiece. Harry continued painting at this level for several more years, and because of his fame, his work was exhibited in the most prestigious and visible venues. But technology was overtaking him. From the 70’s onwards, photography had become the preferred medium for advertising. Harry carried on painting for Esso (later Exxon), Humble Oil, John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company and Redbook. He also continued his devotion and professional relationship with the Seventh Day Adventist Church and the Review and Herald. By now, Harry was in his eighties and painted just for enjoyment.

In recognition for the 70 years of his professional life, he received the Grumbacher Purchase Prize from the American Watercolour Society, the Clara Obrig Prize from the National Academy of Design, and numerous awards from the Art Directors Club. Additionally, he was elected to the Illustrators Hall of Fame in 1994. Harry died in 1996, aged 90.

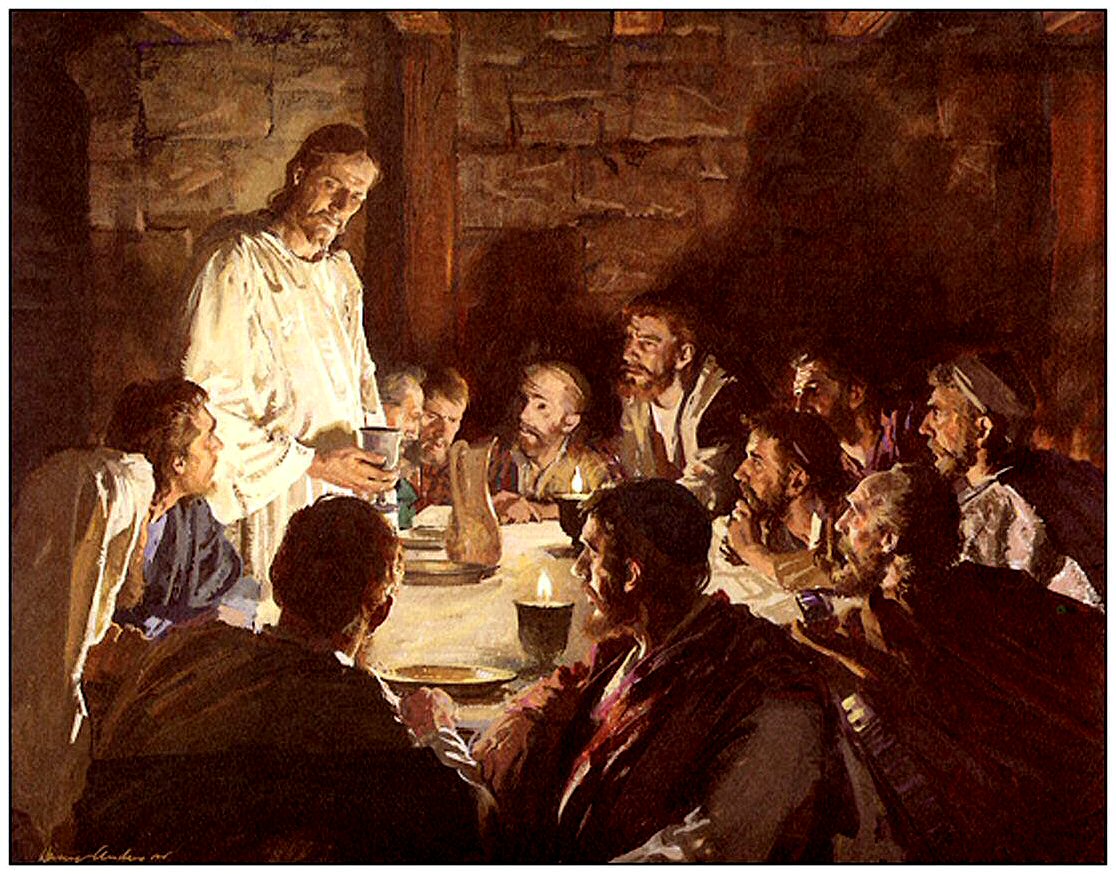

But where’s the Last Supper? Well, this is Harry’s Last Supper, and it’s the most believable last supper of them all. There is no huge table as Da Vinci painted, or the great feast with half a dozen servants as Tintoretto painted, and nobody bought a place at this table. Harry was meticulous about detail, and he painted what he thought that meeting so long ago in one of the poorer houses of Jerusalem would have looked like. The dress of the disciples is that of men who have wandered from town to town following Jesus as he preached. They all eat frugally, and now Jesus tells them that he will be betrayed in the morning and must die soon. The photograph here is poor, but the painting is up to Harry’s high standards and is beautifully done.

We’re nearly at the end of the last suppers. I have missed out half a dozen worthy of mention. In fact, there are hundreds more Last Suppers, but they would have become tedious.

There is only one more Last Supper left, and I know that you will enjoy it.

4

Like

Published at 9:01 AM Comments (0)

4

Like

Published at 9:01 AM Comments (0)

A love lost, but a faith renewed.

Saturday, February 13, 2021

Jacques Joseph Tissot was born in Nantes in October 1836, France to a fervent Catholic family. His father, Marcel Théodore Tissot, was a successful drapery merchant and his mother, Marie Durand, was a designer of hats. Marie instilled in her son a pious devotion to her Catholic faith. Jacques spent his youth in Nantes, and many of his later paintings contained river scenes and the shipping that he would have seen working up and down the River Loire. His father was adamant that Jacques would follow him in the family business, but by the time he was 17 the boy knew that he wanted to be a painter. His mother supported him in his choice of career, and Jacques decided that he would change his forename to the more anglicised James.

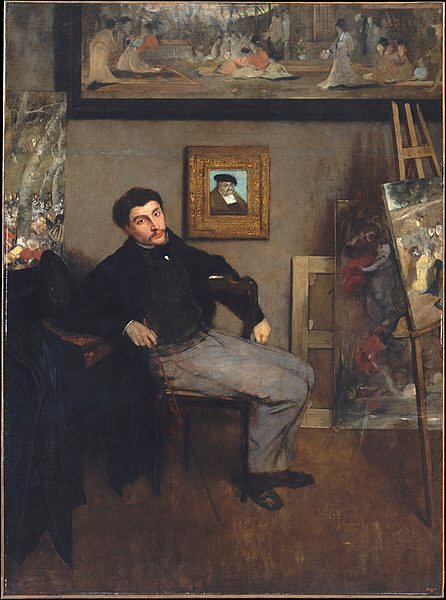

In 1856 or 1857, Tissot travelled to Paris to enrol at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts to study in the studios of Hippolyte Flandrin and Louis Lamothe whilst lodging with a friend of his mother, painter Elie Delaunay. Around this time James began meeting other influential artists of the day, the American James McNeill Whistler, and French painter Edgar Degas who was studying in the same school along with Édouard Manet. His first exhibition was in the Paris Salon in 1859 during which he displayed five paintings. Success for James came a year later when the French government paid 5,000 francs for The Meeting of Faust and Marguerite, which he again exhibited the following year along with other paintings. Fellow artists, Claude Monet and Alfred Stevens were exploring Japanese art, and James also dabbled with the theme for a while before returning to his more familiar subjects. It was during this period that his friend, Degas, painted James’ portrait working in his studio.

Degas' portrait of James now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

He became an international artist when he exhibited in the 1862 international exhibition in London at the gallery of Ernest Gambart and James sensed that if he changed his approach he would be more successful. He began to accept commissions for portraits and scenes depicting contemporary life and was rewarded with critical acclaim.

Un dejuner, 1836 Un dejuner, 1836

Things were going well for James until the States of the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia decided to invade France in 1870. The war lasted seven months, from July 1870 to 28 January 1871. The Germans defeated the French armies in northern France and surrounded Paris, which fell on 28 January 1871, and just two months into the war, the French formed a new government for national defence and fought on. James was living in Paris, and when the Germans took the city, the Parisians formed a revolutionary group called the Paris Commune, which seized power and held the Germans at bay for two months. Tissot joined the Garde Nationale and fought with them on the barricades, more to protect his own belongings from looters than fighting for an ideal. The commune was bloodily suppressed by the regular French army at the end of May 1871, and having seen enough of war Tissot packed his bags, gathered his belongings, and sailed for London.

He had enough money to buy a house in St John’s wood, and found that his good reputation had preceded him. He had already worked as a caricaturist for Thomas Gibson Bowles, the owner of the Vanity Fair and he resumed his work for the magazine using the pen-name Coïdé. He gained admission to the Arts Club of London and Invitations to exhibit at the Royal Academy soon followed. By 1874, one jealous critic wrote sarcastically that he had “a studio with a waiting room where, at all times, there is iced champagne at the disposal of visitors”. In 1874 his old friend Degas asked him to return to France and join a new movement of painters who called themselves the Impressionists. Tissot declined, though he never lost contact with his old friends, and travelled to Venice with Édouard Manet and regularly saw Whistler, who influenced his Thames river scenes.

His decision to remain in England brought James his greatest reward when in 1875 he met a young divorcee called Kathleen Newton. She moved into his house in St. John’s Wood in 1876 and gave birth to a boy, Cecil George Newton. She lived with James for the next six years before she died of consumption in 1882. In the years that followed, James always referred to his time with Kathleen as the happiest days of his life. Despite all the acclaim for his art and the money that he had earned, nothing could replace the love of Kathleen and the family that he had briefly found.

James' portrait of Kathleen James' portrait of Kathleen

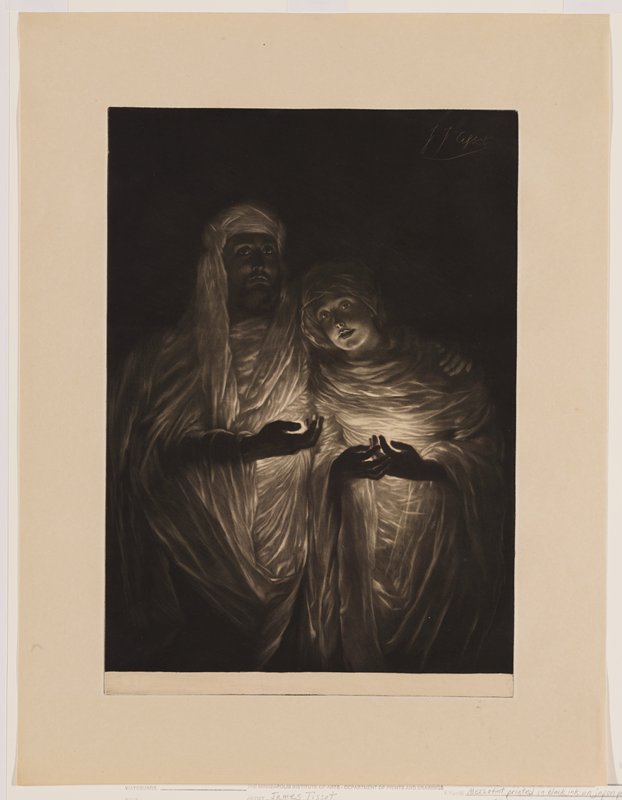

The loss of Kathleen led to a profound change to James’ life. There is a little known painting of his that had been assumed destroyed or lost for decades. It is now in Tissot’s collection of photographs and paintings in his studio in the rural Bouillon region of southern France. It’s called The Apparition. After her death he visited several spiritualists, but the dark painting shows the well-known spiritualist and medium, William Eglinton, accompanied by a woman. Both are shrouded in white and holding orbs of light. It is supposedly based on a vision Tissot had in a séance with Eglinton.

Shortly after Kathleen’s death Tissot returned to France, but he was not the same man who left a few years earlier. When all of France was buzzing with Impressionism, James changed to watercolours and he began painting biblical pictures. Some have argued that he took advantage of a growing movement of Catholic revival, but his conviction to his new theme was strong enough for him to visit the lands of the Bible. Between the years of 1886 and 1896 he travelled to the Middle East three times to make sketches of the people and towns. His watercolours, always well researched, moved towards realism and accuracy of detail. He produced a series of 365 gouache watercolours which he exhibited in France in 1894/5, London 1896 and New York in 1898/9. In 1900 the Brooklyn Museum bought the collection and published them in two versions; one in French and the other in English. After the first exhibition in France in 1895 Tissot was awarded the Légion d'honneur, France's most prestigious medal. James carried on painting subjects from the Old Testament and exhibited 80 of them in Paris in 1901.

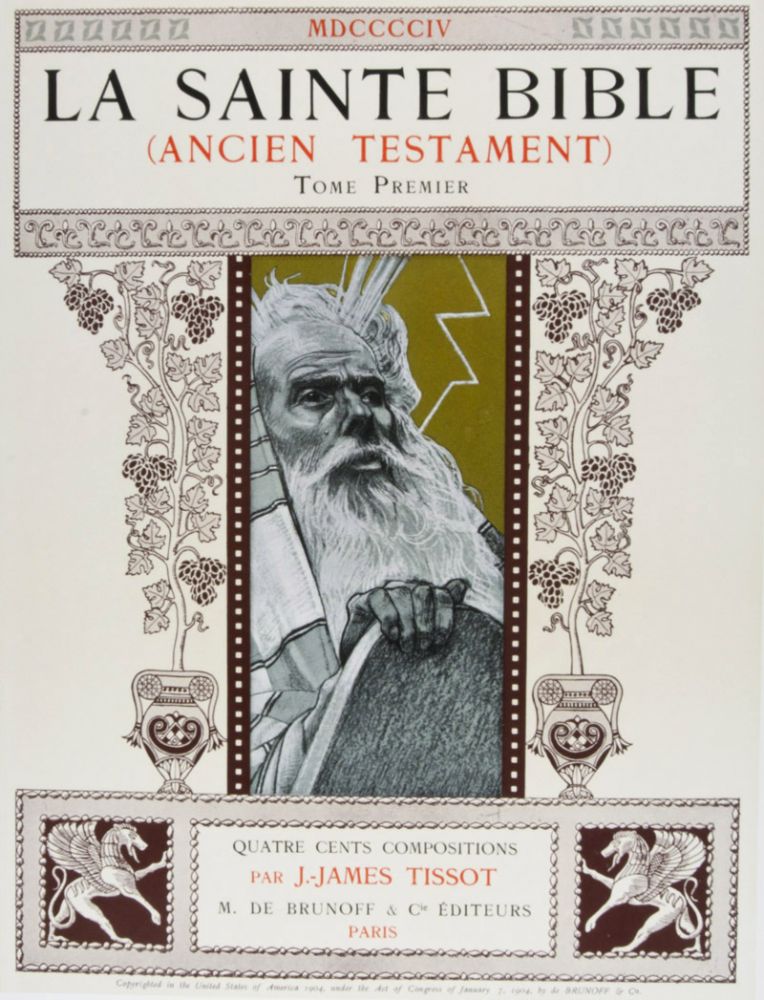

Tissot's illustrations for sale on the internet, second hand at £3,760. Published by M. de Brunoff & Cie, Paris, 1904

One of the gouache paintings that he painted was the Last Supper. If you remember the Agape Feast drawings in the catacombs of Rome, the people at the table were laying down on beds. This is what Tissot saw for himself on his visits and accurately drew in his pictures. The table is sparse, but the symbolic Holy Grail is placed in front of Jesus. He painted another picture whose theme is less familiar, but will show up again later on. It shows the disciples standing in a circle with Jesus on the right apparently blessing them. Both paintings convey an air of sadness and knowledge of the horrors to come.

That could be the end of the story, but there’s more.

Tissot’s depictions of the Holy Land had a historical value, and when film director William Wyler began a remake of the 1925 silent film Ben Hur in 1959 he began looking around for authentic biblical scenes. His researchers showed him Tissot’s drawings and he used many of them for his scenes, especially What our Lord Saw from the Cross.

When George Lucas was writing The Raiders of the Lost Ark in the 1970’s he had to ask what the Ark of the Covenant actually looked like. He was shown Tissot’s Moses and Joshua in the Tabernacle and The Ark Passes over the Jorden and when the time came for making props he ordered copies of Tissot’s ark to be made for filming.

Just to add a topical note. The Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in northern Ethiopia is the reputed resting place of the real Ark of the Covenant. According to the Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, it was taken there by the Queen of Sheba’s son Menelik and King Solomon of Israel after Jerusalem was sacked in 596/587 and Solomon’s temple destroyed. It has been guarded by monks who are forbidden to leave the church grounds until death. The war that is going on there is putting the ark in danger. Eritrean troops have been looting churches in the area and reports of mass shootings of civilians and photographs of damage to the church are emerging. I write theses blogs sometimes weeks in advance, so by the time you read this there may be more news.

0

Like

Published at 9:44 AM Comments (6)

0

Like

Published at 9:44 AM Comments (6)

Chalk or cheese for supper

Saturday, February 6, 2021

We are now in the middle of a string of Last Suppers, but they are of a different mettle to those which came before. Leonardo made a bold statement with his imposing fresco, but some of the faces might have been taken from Leonardo’s grotesque sketches, and the almost mathematical spacing of the disciples along the table was very formalised, but meant that none of the disciples had their backs to the viewer. These next two artists made their Last Suppers much more believable.

Vicente Juan, known as Juan de Juanes was born in Fuente la Higuera, Valencia, in 1523. His father was an artist who was influenced by Raphael, and Vicente followed in his father’s style, but he has infused some Italian influence into his paintings. He uses bright colours combined with a high technical skill, and is one of Spain’s best known and most liked religious painters. In Spain, this is the definitive Last Supper, not Da Vinci’s. Each disciple has a halo with his name painted within it. Only Judas has no halo, and he is at the far right with his body half turned away trying to hide the purse containing the bribe to betray his master. Their faces are those of real people filled with adoration as Christ explains the Eucharist to them. Juan was the forerunner to most of the Spanish religious painters and sculptors whose continuing work you can see in all parts of Spain.

His family was devout catholic, and Juan never painted a profane subject. Before he began each painting he took Holy Communion, and the progress of the painting was accompanied with solemn prayers and fasts. He was never short of patronage from the church, and his patrons included the Jesuits, Dominicans, Minims, Augustinians and Franciscans. Juan’s style is the one adopted by many of Spain’s religious painters and can be best seen in the Sagrada Familia shown below. All his surviving work is in Valencia, and his work was continued by his son and two of his daughters who were all painters in their own right. His life was successful and profitable, but not very interesting. His Last Supper now hangs in the Museo Del Prado, Madrid.

Sacred family. Holy Family for the sacristy in the Cathedral of Valencia.

The next artist we look at lived his life a little on the wild side. And the lifestyles of the two artists together are like chalk and cheese.

Valentin de Boulogne was born in Coulommiers, France. His father and uncle were both artists, and he probably trained with them before setting out on his own. He first moved to Paris, but he soon learned that all the action was in Rome. He arrived there in 1620 and just missed meeting the art world’s second most famous bad boy. (Adolf Hitler has first place.)

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s work emphasized the common humanity of the apostles and martyrs and rejected the Mannerism that had preceded him. His paintings were three-dimensional, showing real people with expressions that displayed the full range of human emotions. He had initiated the Baroque era, and his style had attracted a large following from all parts of Europe. However, his lifestyle was as famous as his artwork, but for all the wrong reasons. Caravaggio had fled Rome just a few years before Valentin arrived, but he had left a legacy worthy of Rome’s lurid past.

As early as 1590 Caravaggio had a reputation for street brawls amongst gangs of young men in Milan. He committed a murder there and had to flee to Venice and then to Rome. Less than a decade after arriving in Rome, he was arrested for beating a nobleman with a club and he was frequently imprisoned for brawling. After one such spell of imprisonment, he knuckled down to painting for three years, but he was arrested in 1603 for defamation and sued. His imprisonment followed, but the French ambassador, who was his patron, stepped in and had him put under house arrest instead.

But it was in 1606 that he stepped over the line between saint and sinner. He had argued several times with Ranuccio Tommasoni, a gangster and the son of a wealthy local family, but this dispute ended in a duel in which Tommasoni was killed. It’s not clear whether his death was intentional, but Caravaggio was trying to castrate his opponent with his sword, and I don’t think that Tommasoni would have held still for that. Caravaggio was sentenced to beheading for murder and an open bounty was declared, enabling anyone who recognized him to legally carry the sentence out. Caravaggio was forced to flee from Rome to Naples, then Malta and finally Sicily.

Simon Vouet, self portrait. Simon Vouet, self portrait.

Valentin de Boulogne joined the studio of Simon Vouet, who was at that time very well established in Rome. Whilst Valentin was studying with Vouet, the latter was elected to be president of the Accademia di San Luca and was commissioned to paint an altarpiece for St Peter’s in Rome. Things could not have looked better for Valentin, and if he had stayed with Vouet, his life might have gone in a very different direction. Summoned in 1627 by the King of France, Vouet became Premier peintre du Roi, and was commissioned to paint portraits and decorate the mansions of royalty for the rest of his life. But Valentin chose a different route to immortality.

Valentin arrived in a Rome that was full of Caravaggio imitators, both in lifestyle and in art. He was one of many ex-pats (no offence intended) who came for one reason, but stayed for something else entirely. It was not long before he was initiated into the Bentvueghels (Dutch for “Birds of a Feather”) a group of mostly Dutch and Flemish artists who were known for their drunken celebrations and near worship of the Roman god, Bacchus. The initiation ceremony was usually paid for by the initiate, and consisted of a piss-up that could last for a whole day and night. For those who could still walk, the conclusion to the day was to stagger together to the Church of Santa Costanza, which was popularly known as the Temple of Bacchus, and surround the sarcophagus of Constantina, the eldest daughter of Roman emperor Constantine the Great, which had sculpted scenes depicting Bacchus on its sides. Here they raised a glass to toast the old Roman god before going home. Because of his Christian name, Valentin was given the nickname inamorato, meaning one in love.

Initiation into the Bentvueghels. Initiation into the Bentvueghels.

Perhaps I have painted a rather gloomy picture of Valentin and his friends, because they actually maintained a very high standard of art, despite their bad behavior off-canvas. Valentin’s social life was in the bars and dives of Rome, and this shows in his artwork. For me, the ones who came before, and some who came after, lived in an ecclesiastical bubble dictated by their patrons’ purse strings. Valentin stepped outside these confines and showed the realities of life in the streets, the life that Jesus might have seen. The Fortune-teller is a beautiful example of his mastery of this theme.

A gypsy fortune teller is entertaining a group of young soldiers unaware that her purse is being stolen by a thief. The thief looks at the viewer with a conspiratorial eye, unaware that his pocket is being picked by a child. The intrigue apart, the sheer mastery of light, the credible emotions on the faces of the soldiers and the detail in the painting is stunning. We are so accustomed to photography and cinema now that we see this and think little of it, but in 1630 it was amazing.

So now we come to the Last Supper by Valentin. He has moved Judas to this side of the table on the left, and painted him surreptitiously holding a purse of gold behind his back. The faces of the disciples are entirely credible and their clothes are those of men who have spent the last few years on the road preaching. Valentin masterly paints the emotion of shock and disbelief that the real disciples must have felt. To me, this is a high point in the art of the suppers, and is only surpassed much later on. Many of his seventy or so paintings depict faithfully the whole range of emotions known to man and he could have become one of the great artists of the era.

Is there happy ending? Well, he may have been happy at the time, but the tragedy is that Valentin de Boulogne died at the age of 41. His cause of death … he had been on a drinking binge all day and he decided to round off the evening by bathing in the freezing cold waters of the Fontana del Tritone on Piazza Barberini. During the following few days he developed pneumonia and died.

There may be a lesson here, but who am I to preach.

4

Like

Published at 10:42 AM Comments (2)

4

Like

Published at 10:42 AM Comments (2)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|